The Real Reason George Washington Executed The First Presidential Pardon

Presidential pardons are one of the job's perks. During his 2017-2021 term, President Donald Trump gave 143 pardons — many more than President George H.W. Bush's 74 from 1989 to 1993, but less than President Obama's 212 from 2009 to 2017. The most pardons happened during President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's reign from 1933 to 1945, when he offered a whopping 2,819 of them (via Pew Research). But, then again, FDR was elected for four terms, dying less than a year into his last one, according to ThoughtCo, so he had more time to be forgiving.

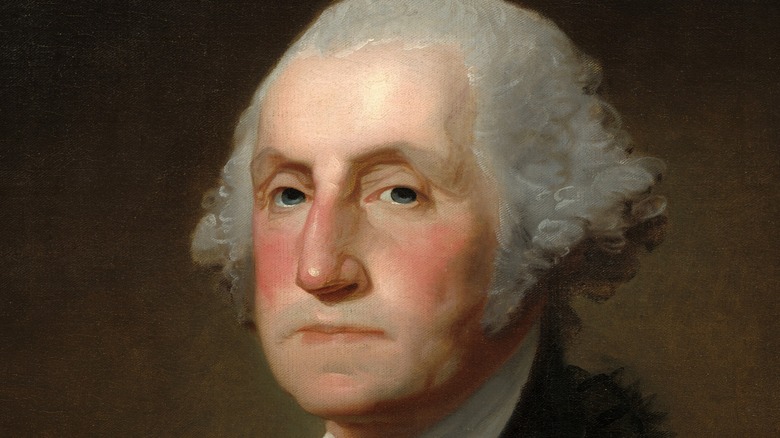

Our founding father and initial president, George Washington, gave the first pardon. This power allows a person to receive exemption for committing a crime, explained Nolo. Typically, this decision is final and decided on by the executive, who considers things like public welfare and injustice before making their determinations. While pardons may forgive someone of a crime, and the subsequent punishment, they rarely expunge the conviction the individual received — so the person pardoned is still considered "guilty" and needs to do things like list the offense on job applications.

The first presidential pardon on November 2, 1795, pitted two political rivals against one another in the name of whiskey (via Smithsonian).

A fight over a whiskey tax begins

The treasury secretary and founding father, Alexander Hamilton, believed in the Excise Whiskey Tax, passed by Congress in 1791, which taxed those who produced the drink. Hamilton thought the tax was the solution to all the national debt that existed from the Revolutionary War, according to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Some, like the large commercial distillers in the east simply passed the expense of the tax to customers, but smaller whiskey makers, mostly in the west, opposed it. Those in the western regions faced more challenges as well — transport required greater distances on poorer roads, often undeveloped.

The federal government had little success collecting the tax from these areas, and Hamilton urged the president to become involved. Finally, on September 15, 1792, President Washington issued a proclamation that condemned anyone who disrupted the "operation of the laws of the United States for raising revenue upon spirits distilled within the same," reported the TTB.

The first official pardon ends the Whiskey Rebellion

Still, rebels continued ignoring the tax and abusing those that tried to implement it. Eventually, the rebellion against the whiskey tax hit a head when General John Neville received a warning that a crowd was approaching. When the group neared his home, he shot an opposition leader, according to Smithsonian. The next day, more than 400 men forced him to surrender his office.

Hamilton led an army to the site in southwestern Pennsylvania and arrested about 150 suspects, with just 10 facing a trial. Per the magazine, of those 10, two received a conviction: John Mitchell and Philip Weigel were sentenced to hang. Washington, who never fully embraced the tax, pardoned both men.

"The misled have abandoned their errors," he said in his Seventh Annual Address to Congress. "For though I shall always think it a sacred duty to exercise with firmness and energy the constitutional powers with which I am vested, yet it appears to me no less consistent with the public good than it is with my personal feelings to mingle in the operations of Government every degree of moderation and tenderness which the national justice, dignity, and safety may permit."