The Untold History Of The Pan-African Congress

Although the Pan-African congresses no longer happen in their original form, they spurred an international movement that sought to underline self-determination and self-governance for African people and Black people in the diaspora. And although the Pan African congresses had comparatively little political or financial power, they set the stage for international discussions about racism and colonialism.

Several African leaders such as Patrice Lumumba, Kwame Nkrumah, and Nnamdi Azikiwe ended up participating and being greatly influenced by the Pan-African movement, and it was ultimately from the seeds of the Pan-African Congress that the Organization of African Unity came into being, writes Black Past.

The Pan-African congresses technically ran from 1919 to 1945, but anti-colonial solidarity was alive well before and well after the congresses ran their course. As of 2021, the anti-colonial and anti-racist struggle still isn't over, but the history of the Pan-African congresses shows us that the ability to come together internationally is critical towards any global struggle.

The history of the Pan-African Congress

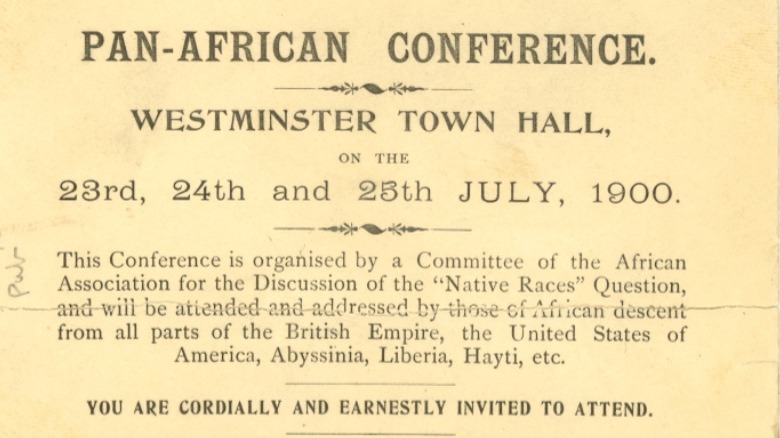

One of the first organizations created to encourage Pan-African unity was the African Association, founded by Henry Sylvester-Williams, a Trinidadian barrister, in London in 1897. Face2Face Africa writes that within a couple of years, the African Association was able to successfully bring together Africans in the diaspora, especially those who were "interested in the idea of setting Africa free from its colonisers."

According to Black Past, Sylvester-Williams also wanted to give Africans and the African diaspora "a forum to address their common problems." This motivated the Pan-African Conference of 1900, organized by Sylvester-Williams from July 23-25. According to Afropean, there were five stated aims of the 1900 Pan-African Conference, which included securing "true civil and political rights" for Africans across the globe.

W.E.B. Du Bois was present at the conference, as was Henry Francis Downing, Anna J. Cooper, John Alcindor, and there were at least 30 delegates who represented countries of the African Diaspora. And although most from the West Indies and England, this was one of the first international meetings that sought to address the effects of colonialism and the legacy of slavery.

The Pan African Association was also established during the conference, chaired by Bishop A. Walters and Du Bois, among others, and together they drafted "To the Nations of the World" (posted at Black Past), an address which demanded freedom for Black people and colonized African countries, which was given as the closing remarks of the conference.

The first Congress meets

While European and American politicians got together for the peace conference in Versailles and discussed, among other things, "the future of Africa," Du Bois decided it was time to organize another conference. And so as the Paris Peace Conference went on in Versailles in 1919, the 1st Pan-African Congress was convened in Paris, writes Black Past.

According to Face2Face Africa, the main purpose of the first Pan-African Congress was to protest the Paris Peace Conference, which only included one Black representative, Lecba Elizier Cadet, and to "demonstrate the existence of Black leaders and discuss the Black community's role in the War." Decolonization was also heavily underlined.

In "The Elusive History of the Pan-African Congress, 1919–27" (published by History Workshop Journal, posted at Oxford Academic), Jake Hodder writes that the first Pan-African Congress met in the Grand Hôtel in Paris, although some historians have misplaced it at the Palais de Justice. Several individuals holding public office were in attendance, and although participation by state officials would wane by the last few congresses, "the participation of colonial ministers and diplomats remained a dominant feature in reports." However, lists were also often done in an "impromptu fashion," with few delegates traveling "specifically for the Congress." Fifty-seven delegates were able to attend, but some people were unable to get to Paris because they were denied visas by the United States or the United Kingdom.

The second in several sessions

The 2nd Pan-African Congress was held in August and September 1921 across London, Brussels, and Paris. Hodder notes in "The Elusive History of the Pan-African Congress" that the dates for the congresses are sometimes inconsistent or will mention sessions in cities sporadically. But rather than being due to "a disregard for historical accuracy," Hodder argues that because the conferences were organized on a thin budget and were often prone to changes on short notice, the difficulty in establishing a precise timeline may in fact be representative of the congresses "improvisational nature."

Du Bois repeatedly sought out "educated Black leaders" and prestigious delegates in order to get "official recognition from the Government." According to the summary of the 2nd Pan-African Congress (posted at University of Massachusetts Amherst), 113 delegates were present, representing 26 different countries. Echoing the previous meetings, the 2nd Pan-African Congress reiterated the need for "local self-governance for colonial subjects" and derided imperialism and racism, per Black Past.

However, the conversation about colonialism during the 2nd Pan-African Congress led to such a heated debate between the French and American delegates, due to the French delegate's "reluctance to criticize colonialism," that French participants refused to attend the 3rd Pan-African Congress. Black Americans in France would later end up attending, but as participant Ida Gibbs Hunt wrote to Dubois, they "represented no one but ourselves," reports Hodder.

Reiterating calls for self-rule

The 3rd Pan-African Congress met in London, England and Lisbon, Portugal in November 1923. Some white European people, including H.G. Wells, were in attendance during the London session, per Black Past.

The University of Edinburgh writes that the 3rd Pan-African Congress was comparatively less organized and less well-attended. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had been involved with the first two congresses and had provided funds, but by the 3rd congress, the Pan-African Association determined that the NAACP was "primarily, although not exclusively, interested in the local American race problem [...and] could not do anything further for the Pan African movement except in a small way," according to the summary of the 3rd Pan-African Congress (also posted at the University of Massachusetts Amherst).

This congress was also the first time that the National Association of Colored Women sent representatives. And although, there were women like Ida Gibbs Hunt who'd been attending the congresses from the very beginning, writes Pan African Congress, they have often been written out of the movement despite the "frontline role" they played.

The 3rd Pan-African Congress once more called for self-governance and the necessity of addressing whether or not Black people are "to be regarded as human beings potentially the equals of other human beings." However, some people, like Gratien Candace of Guadeloupe and Blaise Diagne of Senegal, believed that any reforms or developments had to happen within colonialism, which led them to them breaking away from the Pan-African Congresses.

Inhibited by travel restrictions

The 4th Pan-African Congress was held in New York City in August 1927, but they ended up running into many of the same problems as they'd faced during the first congress, the biggest of which was being inhibited by travel restrictions.

According to "The Pan-African Congresses, 1900-1945," posted at Ohio State University, only 10 countries were represented other than the United States, and Africa was only represented by delegates from Nigeria, Liberia, the Gold Coast, and Sierra Leone. This was due to the fact that British and French colonial powers had imposed travel restrictions "in an effort to inhibit further Pan-African gatherings." As a result, the 4th Pan-African Congress was largely made up of Black American women.

Pan African Congress writes that the 4th Pan-African Congress was organized by Addie W. Hunton and 21 other Black women, many of whom were part of "The Circle of Peace and Foreign Relations," an anti-war women's organization.

In the early 1920s, there was a sense of trust in the League of Nations "to give rise to a new age of enlightened global governance, yet its inclusive language masked a new permanent reality of racial hierarchy," Hodder writes in "The Elusive History of the Pan-African Congress." As a result, as anti-colonialism started finding commonality with the emancipation of the working class and "liberal internationalism" was seen to be lacking, by the 4th Pan-African Congress, "all references to the League of Nations had been removed from its resolutions."

The last Pan-African Congress

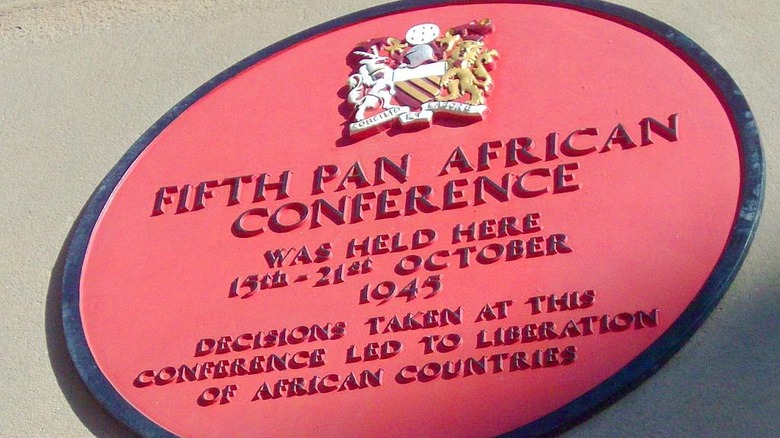

Due to the Great Depression and the Second World War, the Pan-African Congress ended up being suspended for almost 20 years. But in October 1945, it was revived for one last meeting in Manchester, England, although it's unclear if the meeting was initiated by Du Bois or George Padmore.

"The Pan-African Congresses, 1900-1945" writes that the 5th Pan-African Congress was notable not only for representing more Africans, but more members of the working class as well. The previous congresses had been comprised mostly of "Black middle-class British and American intellectuals," but the Manchester congress "was dominated by delegates from Africa and Africans working or studying in Britain."

The 5th Pan-African Congress was largely organized by Amy Ashwood Garvey and Amy Jacques Garvey and featured "major forces of decolonization," including Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta. Trade unions were also strongly represented, writes the Pan African Congress.

Du Bois believed that once Ghana was independent, then the next Pan-African congress would take place in Ghana. But after Ghana declared independence in 1957, Du Bois found himself unable to travel because the United States government impounded his passport. As a result, in April 1958, the All African Peoples Conference in Accra, Ghana was organized instead by Nkrumah and George Padmore.