Awful Science That Led To Everyday Treatments

Humanity has come a long way from disgusting medical treatments and the early medicine that often did more harm than good. These days, drugs follow a meticulous and stringent process of development, trials, and approval, typically taking months or even years. All of those steps help reduce the chances of people suffering weird or dangerous side effects from the stuff that's supposed to make them feel better. They're also a guarantee that drug developers follow rigorous scientific procedures, instead of just putting sugar or cement into gelatin shells and calling it medicine.

However, many of today's everyday drugs and treatments trace their roots to the work of medical professionals and scientists whose methods were, to put it mildly, less than scientific. Admittedly, in the past, drug development regulations weren't as strict as they are now. In fact, a major reason why today's rules are so much stricter is because society has learned so much from the medicinal mistakes of the past. Back in the day, people turned a blind eye to — and sometimes even lauded — the daring clinical trials and deceptive experiments of certain doctors and scientists, many of whom wholeheartedly believed they were on the right track. Now, the following examples of irresponsible drug development "science" could easily land anyone a very long stay in the slammer (and rightly so).

The father of vaccination experimented on a child

Dr. Edward Jenner's name has become synonymous with vaccines. Recognized as the father of immunology, his groundbreaking work on vaccines is said to have "saved more lives than any other experiment in history" (via Science Focus). Unfortunately, said life-saving experiment was unethical, and involved an innocent child.

As far back as 3,000 years ago, civilizations across the world had to deal with a deadly disease called variola (reportedly named for the Latin words for "stained" or "mark on the skin"). According to the Centers for Disease Control, historically this illness, also known as smallpox, killed three in every 10 patients who contracted it.

In 1796, Jenner investigated cases of milkmaids becoming immune to smallpox after getting a relatively less dangerous disease called cowpox (via Science Focus). He decided to test this theory by taking material from a cowpox sore, scratching it into a small boy's arm, and then exposing him to smallpox. Fortunately, it worked, and over the years, Jenner and other scientists refined the smallpox vaccine, leading to the disease's eradication two centuries later.

But Jenner wasn't really the first to realize that disease exposure could grant immunity. As explained in "The Myth of the Medical Breakthrough: Smallpox, Vaccination, and Jenner Reconsidered," before Jenner's time people already knew that smallpox survivors gained immunity to the illness. Furthermore, exposing people to cowpox to give them immunity (also called variolation) was already practiced in the early 1700s. However, Jenner was the first to approach the process systematically.

Modern gynecology stems from horribly unethical practices

These days, the speculum — a duck-billed tool for separating the vaginal walls during medical examinations — is part of every gynecologist's toolbox. And while the idea of using an instrument like this dates back to ancient Greece, the modern-day speculum (and other gynecological tools and techniques) are attributed to Dr. James Marion Sims, the so-called "father of modern gynecology" (via History). Unfortunately, the methods he employed in his gynecological exams during the late 19th century were anything but fatherly.

As a medical practitioner with neither sufficient training nor a strong inclination towards women's reproductive health, Sims became more interested in the then-controversial field when he realized he could try new surgical techniques on women who were "essentially his property." Indeed, according to STAT, Sims carried out many untested gynecological procedures on numerous Black slaves at his Alabama hospital. In his memoir, he recounted using a bent spoon to inspect a slave named Betsey, and another patient, Anarcha, reportedly suffered through 30 operations without anything to dull the pain (via the New York Times).

He even used Black children in his surgical experiments, justifying his methods with his belief that African Americans were mentally inferior and his insistence that the slaves were actually clamoring for his treatments (a claim backed by no evidence). Hardly surprising for a man who blamed patients' deaths on "the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the Black midwives who attended them."

Virologists developed the flu vaccine by infecting patients without consent

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the influenza vaccine saves millions of lives every year. Developed through research efforts led by microbiologist Thomas Francis Jr. and virologist Jonas Salk (via The Free Lance-Star), the flu vaccine proved to be a boon during World War II, as it helped protect American troops fighting overseas. Sadly, the trials that made the vaccine possible were done on institutionalized patients without their consent — and even involved patients being deliberately infected with the virus.

The University of Michigan Heritage Project explains that medical trial procedures weren't exactly stringent back in the early 1940s. In fact, using mental hospital patients as test subjects for new drugs wasn't just permitted, it was commonplace.

And for such an important and time-sensitive government-sponsored endeavor, Francis, whose experience with influenza included being the first to isolate its different strains, did not hold back on his team's experiments. Thus, when he learned that the absence of a flu outbreak in 1943 meant a lack of test subjects, Francis blasted a full-strength flu spray made from infected mice lungs into the nostrils of 100 patients at Ypsilanti State Hospital, some of whom were vaccinated. The trial was supposed to be double-blind — 100 other patients received a placebo, and no one was supposed to know who got which. Only 16% of the vaccinated subjects got sick, compared to half of the non-vaccinated set.

Live-saving research came from cells obtained without consent

To put it bluntly, numerous medical advancements and milestones — from the polio vaccine to cancer research — owe their existence to the theft and commercialization of a Black woman's incredibly robust cells.

Johns Hopkins Medicine tells the story of Henrietta Lacks, a mother of five who was treated at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951 for vaginal bleeding. Subsequent tests revealed that she had cervical cancer. As part of standard procedure, medical staff obtained genetic samples from Lacks and they were examined in the laboratory of Dr. George Gey. As he was conducting tests, the physician noticed something peculiar: Unlike other samples, which didn't last long under observation, Lacks' cells not only survived, but even doubled on a daily basis.

Lacks ultimately succumbed to her cancer on October 4, 1951. However, research on her cells (named HeLa cells, combining the first two letters of her first name and surname) continued, even though doctors did not obtain her or her family's consent prior to Lacks' death (via the BBC). The HeLa cells have since been grown indefinitely, enabling medical researchers through the decades to study them and test novel drugs, learn how radiation affects human cells, how find out how viruses wreak havoc on the body, and more.

In an attempt to correct this wrong, members of Lacks' surviving lineage have been given a significant part in deciding how her cells should be used. Lawmakers have also bolstered rules on using human genetic material for medical purposes (via Science Focus).

To treat malaria, researchers infected prisoners with it

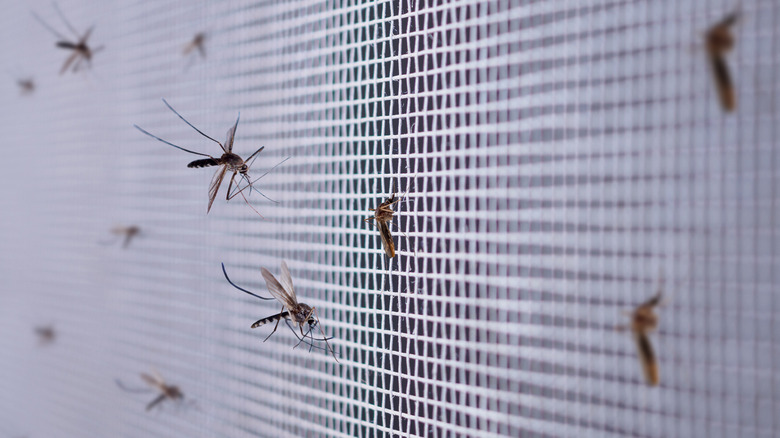

As told in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Illinois' Stateville Penitentiary became the site of the Malaria Research Project, an attempt to study the tropical disease that proved to be a thorn in the military's side during World War II.

The experiment, which started in 1944, involved over 400 volunteer inmates. In an interview with the New York Times 30 years later, project director Dr. Paul E. Carson stressed that the prisoners knew exactly what they were signing up for. Despite their reported full consent, the ethical grounds of the experiment remain dubious — and if the recollections of Stateville inmate and volunteer assistant Nathan Leopold are to be believed, the trials resulted in at least one death.

To test newly developed antimalarial drugs, University of Chicago doctors exposed volunteers to malaria-carrying mosquitoes. According to "Making Willing Bodies: The University of Chicago Human Experiments at Stateville Penitentiary," Leopold wrote vivid descriptions of his headache when he contracted the particularly virulent malaria strand as part of the experiment: "You think from moment to moment that your head is going to split, and you wish to gosh it would!"

As there was no formal research to gauge the true long-term effects of the experiment on the inmates, it is difficult to say whether the mosquitoes did lasting harm to the volunteers. Regardless, the Illinois Department of Corrections stopped the program in 1974 due to its "immoral and unethical" nature. That same year, Leopold died of heart failure, a known synthetic antimalarial drugs side effect.

Acne treatment was born on the backs of abused prisoners

The topical cream tretinoin (also called retinoic acid or synthetic vitamin A) aids in the treatment of acne and sun-damaged skin, as well as in minimizing the appearance of wrinkles. A dermatologist named Dr. Albert M. Kligman played a key role in its development. Unfortunately, so did numerous abused inmates at Philadelphia's Holmesburg Prison, who served as subjects for his tests.

Beginning in 1951, Kligman conducted a series of corporate-sponsored experiments on prisoners, using their skins to gauge the toxic side effects of various substances and cosmetic products (via Discover Magazine). Among these was a dangerous chemical called dioxin, found in the notoriously potent (and now discontinued) herbicide Agent Orange. Kligman reportedly tested this on 75 subjects who did not know about its painful side effects. Even worse was the fact that he gave them a dosage 468 times greater than standard test protocol.

A CNN report details the other horrific tests that Kligman conducted: He studied ringworm infestation among test subjects, used all sorts of previously untested antibiotics, tranquilizers, and oral hygiene products, and even removed inmates' thumbnails "to see how fingers react to abuse." According to Discover Magazine, the tests left the inmates scarred and in great pain. Unfortunately, the destruction of records means that the identities of the participants — and the true extent and possible lasting impact of their suffering — may be impossible to determine now (via California Law Review).

To prove that spinal taps are safe, a doctor did one on a 2 year old

Medical professionals use spinal taps to collect cerebrospinal fluid. By running tests on this fluid, doctors can determine whether a patient has nervous system disorders or cancers. The procedure is also used to deliver cancer treatment drugs and anesthetics (via Mayo Clinic). Back in the late 1800s, though, lumbar punctures were new, and their safety was in question. In 1895, a doctor named Dr. Arthur Howard Wentworth decided that he would prove the safety of the procedure by performing one on a 2-year-old child.

According to STAT, Wentworth did not ask for consent before performing the procedure, nor did he explain the procedure to the child's guardians. Based on a paper published in Pediatrics, the doctor gave a rather disturbing description of how it went down: "Immediately after tapping the canal the child became restless, throwing herself about the bed, clutching at her hair and giving vent to short cries [...] During the attack I felt considerable uneasiness [.]" In the same account, he also admitted that he was unsure whether the child would survive. Fortunately, she did.

Wentworth performed the same procedure on 29 other small children at the Boston's Children's Hospital, all without consent.

To study hepatitis, doctors fed people infected poop milkshakes

Adding infected human fecal matter to chocolate drinks and feeding them to unsuspecting children sounds so evil that only a fictional mad scientist would do it. Unfortunately, this happened in real life, and it was under the supervision of a pediatrician who felt that his actions were completely justified.

Hepatitis (then called epidemic jaundice) was one of the many diseases that made American soldiers' lives hell during World War II. According to Forbes, the search for a hepatitis vaccine prompted the creation of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board. Dr. Saul Krugman, a former military flight surgeon, came knocking on the board's door to pitch his idea for developing the hepatitis vaccine. He even proposed a testing site: Willowbrook State School, an overcrowded Staten Island school for children with intellectual disabilities that was experiencing a hepatitis outbreak. And while Krugman did ask for parents' consent, it was obvious that he left out a few key details about the experiments (via STAT).

From 1955 to 1970, Krugman and his associate Dr. Joan Giles willingly infected children with hepatitis, either via injection or by making them drink the aforementioned infected chocolate milk. Through these disgusting tests, Krugman identified the A and B strands of hepatitis, and was able to develop a vaccine against hepatitis B. Still, none of this erases the fact that a doctor trained to care for children intentionally made them sick by making them drink poop-laced milk.

Women weren't told that they were taking birth control pills

In 1955, Dr. John Rock and Dr. Gregory Pincus had a dilemma. According to PBS, the pair had just concluded a series of successful preliminary tests for their birth control pill, but they still needed the approval of the FDA. For that to happen, they had to conduct bigger clinical trials, which seemed impossible due to how most citizens viewed contraception at the time. Thus, when Pincus set foot in Puerto Rico — an impoverished American territory with a high population that had no legal restrictions on birth control — he felt that he had the perfect solution.

Rock and Pincus quickly set up shop on the island, taking advantage of Puerto Rican women by making them take the pill without fully explaining to them its possible side effects or its status as an untested drug (via CNN). The results seemed promising: an effectiveness rate of 100% when taken properly. However, 17% of the subjects experienced headaches, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, and other side effects. Dr. Edris Rice-Wray, the person heading the trials, reported that due to the number of reported side effects, the drug did not demonstrate an acceptable level of safety. Worse, three participants died, though a definite link to the pill was not established.

Shockingly, Rock and Pincus ignored these findings, prioritizing their target release date over the potential health risks of their pill.

Gay conversion therapy led to epilepsy treatment

For adult patients with epilepsy, deep brain stimulation (DBS) systems can provide relief and control seizures when seizure medication can't (via Epilepsy.com). According to the BBC, part of what made this treatment possible was a series of electrical stimulation trials by neurologist Dr. Robert G. Heath from 1950 onwards. Sadly, many of Heath's experiments had a less-than-noble purpose: The doctor believed he could "cure" homosexuality, which he regarded as a mental illness.

As "Dr. Robert G. Heath: a controversial figure in the history of deep brain stimulation" recounts, Heath was a pioneer in employing electrical stimulation techniques to treat schizophrenics. However, he also used this procedure, which involved drilling into a patient's skull and implanting electrodes into specific parts of the brain, to attempt to convert a gay man into a heterosexual (via Scientific American). In two 1972 papers, he wrote about a successful conversion: A 24-year-old subject, B-19, who reportedly had "highly satisfactory" intercourse with a "lady of the evening" days into the experiment. Closer looks at his work, however, have cast doubt on the integrity and soundness of his work. Apart from inconsistencies in his experiments that failed to follow the basics of good science, Heath may simply have been looking at his data and seeing what he wanted to see.

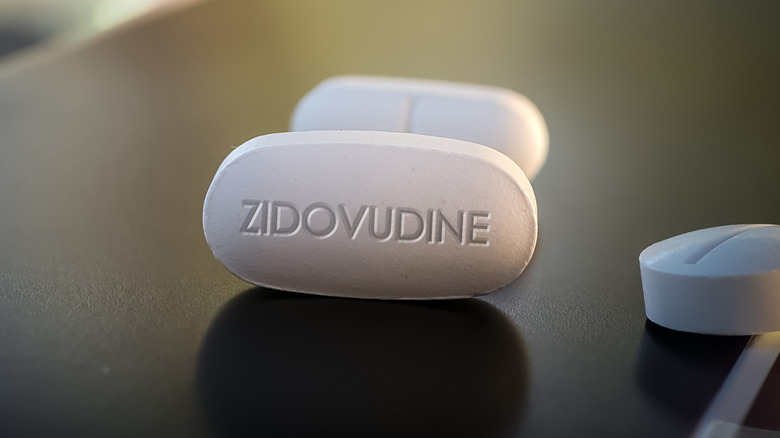

The first AIDS drug was a shelved (and toxic) anti-cancer compound

A combination of public clamor and commercial interests can lead to the development of life-saving meds getting fast-tracked, even without proper scientific basis to support their safety and effectiveness. That's precisely what happened on March 19, 1987, when the first antiretroviral drug for AIDS treatment received approval from the FDA after less than two years of tests (via Time).

According to Spin, AZT (azidothymidine) was developed as an anti-cancer drug 25 years earlier. However, development stopped when tests revealed that it was both costly and indiscriminately destructive to cells (and therefore dangerous). Despite this, it received approval for AIDS treatment based solely on a "double-blind, placebo-controlled study" that not only violated many of the FDA's own rigorous guidelines, but was also prematurely concluded to hasten the drug's release.

Despite the controversies surrounding it, AZT remains in use to this day, prescribed alongside other antiretroviral drugs to maintain its effectiveness (via CATIE).

The 'biggest man‐made medical disaster ever' deformed and killed babies

Nowadays, leprosy patients are able to manage their disease with thalidomide, a drug originally developed as a sedative in the 1950s (via Science Museum). And while the FDA has approved it for treating leprosy and myeloma, there was a time when pregnant women used it for morning sickness and other illnesses. According to Medical News Today, this practice led to at least 10,000 babies being born with deformities, and about half of them dying within months.

Due to early clinical trials, researchers assumed that the drug was perfectly safe for human consumption, saying that it was "virtually impossible" for test animal subjects to receive a dose large enough to kill them. Thalidomide received approval for distribution in 1956, and for five years, anyone could buy it even without a prescription. Sadly, the effects of the medication on fetuses during pregnancy was not well-known to medical researchers at the time, and no pregnant women actually participated in the thalidomide trials. Thus, when doctors started noticing the ill effects of thalidomide on pregnancies, the damage had already been done. Thalidomide was swiftly pulled from shelves, and the controversy sparked a massive review of many countries' guidelines on medicine approval.