What Life Was Like As A Print Worker In The Colonial Era

Printers in Colonial America were as pivotal to the communications of information as today's media outlets are. The labor to produce the written word en masse was more intensive than it is now. However, the practice of getting the written word out to people so that they could make informed decisions and be aware of some of the things going on in the government and in their communities was essential in the Colonia era.

The first printing press came to Massachusetts in 1638, just eight years after the original Puritan colony was established, according to American Antiquarian. It was part of Harvard College and used for both the school and for the colony. It published items like textbooks, legal documents, almanacs, sermons, and catechisms. Printed items also included obituaries, histories, narratives and government proclamations. There was a very religious bent to what was printed, as in keeping with the views of the people the printers served at the time.

A successful newspaper didn't get off the ground until 1704 when the Boston News-letter was established, which remained the only newspaper in the colonies until 1719. Per American Antiquarian by 1740, 16 newspapers — all weeklies — were printed in the American colonies. In 1775, just before the American Revolution, there were 37 newspapers in operation. By then, the life of a print worker had become far more than a physical job.

Printers started off as trades people who worked closely with high society

Working a printing press was a skill, and those who learned that skill produced various types of literature to make their livings. Per American Antiquarian, booksellers and postmasters knew how to use a printing press, so some started a newspaper. In other instances, experienced printers moved to the New World from Europe and started a newspaper or printing business. Over time, the skill was passed on to new generations who were born in the colonies.

In the infancy of newspaper reporting, print workers relied on people to come to them with information or something they wanted to be printed, making them a mouthpiece for government information, as they needed those contracts to ensure an income, according to Oxford Research Encyclopedias.

Printers had low social status and lived "precarious economic lives," yet relied on "gentlemen" of the upper segments of society to provide information to print. Often what was shared was done anonymously, and the printers were bound to secrecy. Still, they were not welcomed in the upper echelon societal groups.

During the early 18th century, much of the information printed in newspapers came from news out of London or Europe, but printers would also send copies of their own papers to fellow publishers in the colonies to share information. Those trades were referred to as "exchanges," and according to Oxford Research Encyclopedias, it was the so-called exchanges that spread a continuity of information across the colonies, which eventually fostered support for America's independence.

Colonial era printers took a stand against publishing misinformation

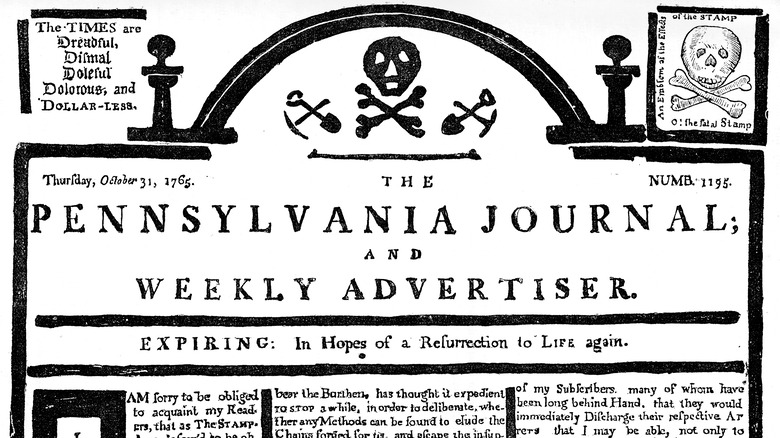

By the 1760s, things were shifting in the world of printers, and in the colonies themselves. With a couple of dozen newspapers available, and ongoing stories about the "imperial crisis," printers and people started taking sides.

According to Oxford Research Encyclopedias, news printers stopped trying to keep their papers neutral by showing both sides of an issue, and instead took a side. Sound familiar? Depending on the leanings of a print shop owner, some papers published things more heavily in favor of breaking away from British rule, while others remained faithful to the motherland.

In some cases, people became hostile against printers who published things they disagreed with, whether pamphlets or newspapers. Other times their safety and property were threatened if they refused to name their sources, per Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Over the course of a century, some colonial printers went from simple trade workers to people who found financial stability and wielded power by the way they could control information that was disseminated to the public, according to the Antiquarian Bookseller's Association of America.

The way Oxford Research Encyclopedias tells it, printers took a stand ahead of the American Revolution. They realized they didn't have to print viewpoints they thought were "lies" or "tyranny."

Oxford Research Encyclopedias wrote, "by giving space to the 'truth' — and, by extension, to the protection of the people's rights — they took a side that changed the older values of press freedom forever."