Here's What Really Happened During The Soviet Invasion Of Afghanistan

When the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the Soviets quickly claimed that the Afghan government had requested for them to intervene. But if the army was there to restrict outside interference, then why were they in fact the ones to murder the president and assume control of the government?

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was neither the beginning nor the end of Afghanistan's occupied history. For centuries, imperial and colonial powers have treated Afghanistan as a pawn towards their own desires, paying little mind to the devastation that they leave in their wake.

While neither the Soviet Union nor the CIA created the mujahideen that was rebelling against the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan before and during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, both foreign powers played a critical role in their expansion, as did Pakistan, creating the circumstances for the Taliban and al-Qaeda to later emerge as well. In the end, while it's impossible to establish what Afghanistan would look like without foreign interference, it's clear that the people of Afghanistan have been repeatedly denied their right to self-determination as foreign powers grasp at influence and resources. Here's what really happened during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Afghanistan's history of colonization

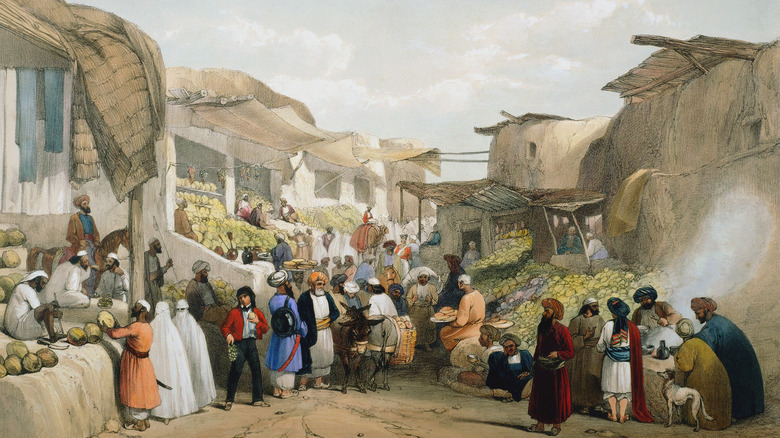

The area now known as Afghanistan has always been at the foreground of imperial conquest, but many of the borders of modern-day Afghanistan were delineated during British colonization. And while the people of Afghanistan didn't refer to themselves as Afghan well into the 19th century, the term began appearing in Persian texts during the 3rd century, according to "Afghanistan" by Stephen Tanner. Historically and today, this term has been used to refer to Pashtuns, Hazaras, Baloch, Aimak, Pashayi, Nuristanis, Tajiks, Turkmen, and Uzbeks, among others.

Known as the "Great Game," believing that Emir Dost Mohammad Khan Barakzai was becoming too friendly with the Russia and hoping to suppress the expansion of the Russian Empire, the British invaded the Emirate of Afghanistan in 1839, per Ariana News Agency. While the Afghan people resisted the invasion, this wouldn't be the last time that the British Empire tried to take over Afghanistan. In 1879, when Dost Mohammed Khan's son Sher Ali Khan had replaced his father as Emir of Afghanistan, the British Empire tried to invade once more. This time, it was able to force Afghanistan to sign a treaty that made Great Britain "the de facto manager of Afghanistan's foreign affairs," according to The Washington Post.

In exchange for control over Afghanistan's international relations, the British Empire subsidized the military forces of local rulers. And by flooding the country with bribes among "local chieftains and favorable bureaucrats," the British maintained their influence for decades.

The Durand Line

The Durand Line, named after British government official Sir Mortimer Durand, is a 1,660-mile-long land boundary created by the British Empire. At the time, it was meant to delineate the divide between Afghanistan and Pakistan, though the latter was still considered part of the British Raj. However, the Durand Line agreement was never even registered with the British Parliament.

According to Afghanistan Online, the line not only cut Afghanistan off from its access to the Arabian Sea and halved its territory, but it also went through the middle of mostly traditionally Pashtun territory. As a result, Pashtuns on the Afghanistan side remained under Afghanistan's jurisdiction while Pashtuns on the other side of the line were now under British rule. Afghan Eye notes that the Durand Line also divided Baloch territory. In response to the signing of the Durand Line agreement, there were waves of protests by Pashtuns and the British Boundary Commission office in Wana, in what is now Pakistan, was burned down. The British Empire ended up sending up to 60,000 soldiers into the region to impose order.

In 1905, the Durand agreement was renewed by Emir Habibullah and in 1919, his successor and son Emir Amanullah Khan reaffirmed the line in the Treaty of Rawalpindi after the war against the British for independence, per Afghanistan Times. However, the Durand Line continued to be rejected by Pashtuns on both sides and there were uprisings every few years.

Establishment of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

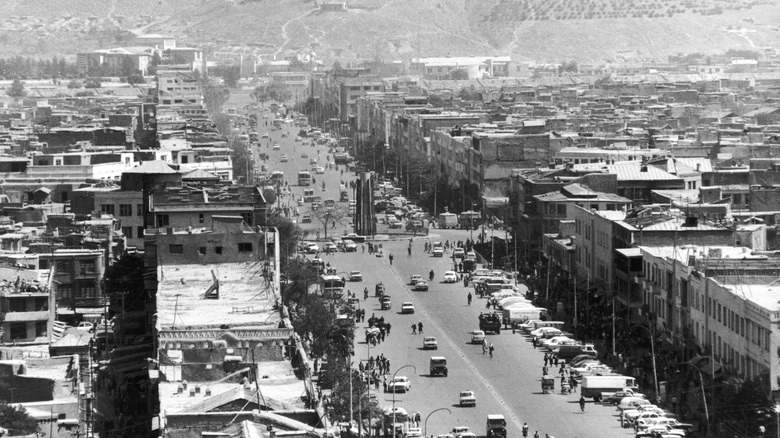

After Afghanistan declared independence from British rule on August 8, 1919, international relations with the Soviet Union opened up for the first time. This would extend over the decades into areas such as Air Force training and equipment for telephone lines, according to Afghanistan Online. Before 1953, the Soviet Union delivered up to 1,000 miles of telegraph and telephone lines to Afghanistan, per Technical Assistance.

However, in response to Emir Amanullah's social reforms, his regime was challenged and soon fell during the Afghan Civil War, and he was replaced by Mohammed Nadir Khan. According to Ariana News Agency, some historians suggest that the British were involved with engineering the uprising. The Kings of Afghanistan, Mohammed Nadir Khan and later Mohammed Zahir Shah, ruled for almost half a century. But in 1973, King Zahir Shah was overthrown in a coup d'etat and Mohammed Daoud Khan became the first President of Afghanistan. However, Daoud's authoritarian regime would only last four years as he tried to play the USSR's and the U.S.'s interest in Afghanistan off one another.

In 1978, Daoud was overthrown and killed in the Saur Revolution, and the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), made up of the Marxist groups Parcham and Khalq, established the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in April. However, the Khalq and the Parcham factions continued struggling against one another after taking power, and eventually the Khalq faction purged the Parchamites from the PDPA, according to Bruce Riedel in "What We Won."

Soviet and American interests in Afghanistan

Throughout the Cold War, Afghanistan was the location of numerous proxy battles over influence and control between the United States and the Soviet Union. And according to The Washington Post, both nations exploited the economic system of corruption installed and encouraged by the British, "funneling large sums of money into Afghanistan ostensibly for infrastructure projects that claimed to modernize the country." Military aid was also given, and all of this was likely in exchange for permission for the Soviets to "conduct petroleum exploration."

Despite all the money being funneled into Afghanistan, much of it was taken by bureaucrats and technocrats, and many Afghans were unable to meet their basic needs. And when the PDPA took over, one of their main resolutions was to put an end to corruption. But as the Soviet Union continued to back the new government, the PDPA never followed through on creating a new economic model that would benefit all the people of Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, during the Nixon administration the United States primarily focused on maintaining economic influence over Afghanistan. But under President Jimmy Carter, the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was seen as too much of a threat by National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. So by July 1979, according to The Conversation, the United States shifted their policy to supplying aid and resources to mujahideen who were rebelling against the PDPA regime.

Life under the Taraki regime

After the Saur Revolution, Nur Muhammad Taraki took control as president of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. According to Newlines Magazine, under President Taraki's regime tens of thousands of Afghans were imprisoned and tortured, and many of them were summarily executed. Those who were arrested ranged from former government officials and village leaders to peasants and laborers with various religious affiliations, per Afghanistan Justice Project. Many were imprisoned and executed at Pul-e Charkhi.

While Taraki's regime claimed to promote gender and ethnic equality, rape was used "as a weapon of war in Afghan villages." And rather than implementing long-term programs with sustainable impacts, the PDPA made superficial changes that were often detrimental towards the women they were meant to be empowering. In "Feminism, Peace, and Afghanistan," Sima Samar writes that the Taraki regime also tried to implement many of its programs by force, such as the set bride price or the rule that women were required to attend a literacy program. Whenever people protested these new regulations, government officials murdered hundreds of people in response.

According to "Afghanistan-A New History," the Taraki regime also imposed a land reform decree that was intended to be a "far-reaching redistribution of land." However, not only did the government do little to enforce the redistribution of land, by threatening the power structure maintained by the landowners, the Mujahideen began rebelling against the PDPA.

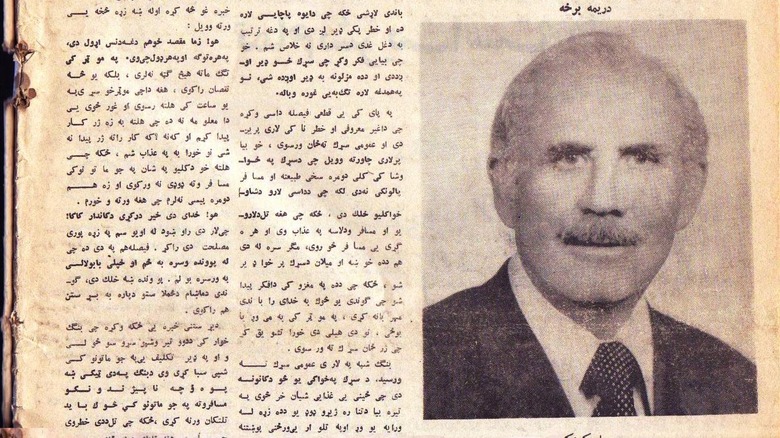

The assassination of Nur Muhammad Taraki

Despite the fact that Taraki and Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin had a close relationship after the revolution, by March 1979, they started to turn against one another. Around this time, Taraki wanted to build a closer relationship with the Soviet Union while Amin wanted to maintain relations with the United States. And according to "Afghanistan" by Mohammed Hassan Kakar, although Amin had built up Taraki's cult of personality, referring to him as the "genius of the East," and was his protégé, Taraki saw Amin's "monopolization of power" and soon they were each looking to get rid of the other.

In September 1979, Taraki and the Soviet Union came up with a plan to assassinate Amin. However, the plan failed, and although Sayed Daoud Tarun was killed, Amin survived. In response, Amin had Taraki arrested. Although there are various accounts as to what happened, it's believed that Taraki was suffocated on October 8, 1979. Amin installed himself as both the head of the party and head of the state, Kakar writes, and began to rule with the impression that the Soviet Union would support him. However, Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev "looked on the killing of Taraki as a personal insult."

The mujahideen rebel groups

Life under Hafizullah Amin's regime was even more brutal and as mass imprisonments and executions increased, thousands of Afghans fled the country. The PDPA was met with resistance from various fronts, but the most substantial opposition came from the mujahideen, also spelled mujahedin. According to Newlines, although the mujahideen were often led by Islamist figures or prominent clerics, many who joined came from various movements and parties. For many mujahideen leaders, the anti-government stance even originated in the early 1970s. The mujahideen weren't organized under a unifying ideology other than being anti-government and consisted of different factions. Some of the factions subscribed to Islamic fundamentalism, while others fought under various nationalistic movements.

Those who faced discrimination previously faced similar prejudices within the mujahideen and the mujahideen also repeatedly committed widespread human rights violations. According to Afghanistan by Nassim Jawad, "In Afghanistan the conflicts were primarily political, not ethnic and religious, and were fueled by superpower politics."

With the mujahideen, the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia saw an opportunity, and even before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the mujahideen were being funded and trained against the PDPA. Those who were fundamentalist were targeted to fight the Soviets because according to Ali Ahmad Jalali, there was a belief that fundamentalist groups would fight more efficiently, while "even nationalists would not have that same ideological fervor impelling them to continue and prolong the war."

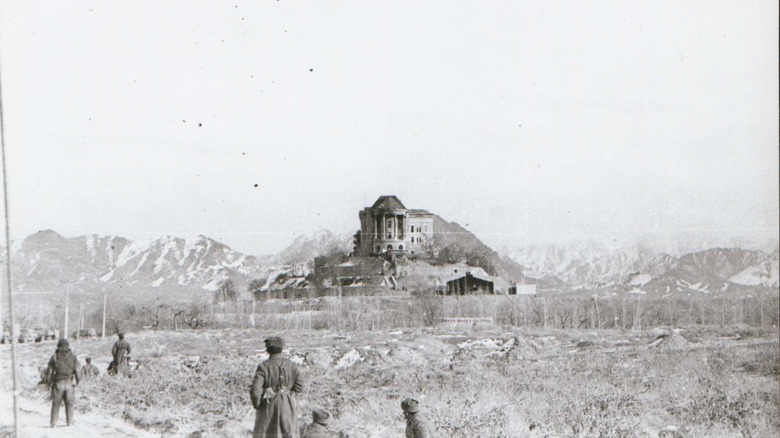

Operation Storm-333

Although the Soviets maintained "business as usual" with Hafizullah Amin, by December 1979, they made the decision to remove and replace him in what became known as Шторм-333, (Operation Storm-333), or the Tajbeg Palace Assault. The takeover was planned for December 14th, but it ended up being delayed by almost two weeks. And even after airlifting Soviet troops to Afghanistan, the Soviet Supreme Council determined that the decision to invade of Afghanistan "was made by a small circle of people in violation of the Soviet constitution, according to which such matters belong to the jurisdiction of higher state bodies," according to "Afghanistan" by Mohammed Hassan Kakar.

Although the Soviets claimed that they were invited to offer "assistance in rebuffing the armed interference from the outside," instead they invaded Tajbeg Palace in Kabul on December 27 and assassinated Amin, although it's unclear exactly how Amin was murdered. In his stead, the Soviets installed Babrak Karmal as president, who had been previously part of the purged Parchamites.

Eyewitnesses recounted that the Soviets used a gas attack against the Afghan soldiers to get into the palace, "causing dizziness, nausea, and paralysis of the limbs," Kakar writes. Everyone in the palace except for Jahandad, commander of the presidential guards, was murdered. But he was also later executed after being imprisoned in the Pul-e-Charkhi prison. And after installing a new government, the Soviets announced that they were going to be sending military aid to Afghanistan as per Afghanistan's request.

The Soviet army in Afghanistan

The Soviet Army remained in Afghanistan for almost 10 years, from December 1979 to February 1989. And according to Pervez Hoodbhoy, the Soviet-Afghan War ended up being the "largest, longest, and costliest military operation in Soviet history." Human Rights Watch writes that up to 115,000 Soviet troops were dispatched to Afghanistan to fight against the mujahideen. All parts of the Afghan government also came under Soviet supervision and even the most menial orders had to be cosigned by the Soviets. Even President Babrak Kamal couldn't make decisions, but he maintained that the Soviets "will never make mistakes in their accomplishments," per "Afghanistan" by Mohammed Hassan Kakar.

During the war, the Soviets used cluster bombs and butterfly mines, many of which still remain in Afghanistan as of 2021. And according to Asia News, hundreds of people are injured or killed every year due to the leftover explosives. Orchards and villages were destroyed in an attempt to keep the mujahideen from using them during ambushes, Ali Ahmad Jalali and Lester W. Grau write in "The Other Side of the Mountain," but at the end of the day, the Afghan civilians were the ones who suffered and the mujahideen were ultimately successful in expelling the Soviets. Irrigation systems and crops were destroyed, and granaries were bombed to keep those in the rural countryside from supporting the mujahideen.

Due to the "scorched earth" policy adopted by the Soviets, Afghanistan's industrial and agriculture output "declined to 40-60% of its [pre-invasion] production level."

Operation Cyclone

During the Soviet-Afghan War, the mujahideen continued to be armed, financed, and trained by foreign powers. According to "The Other Side of the Mountain," the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, Saudi Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates all funneled money and arms to the mujahideen through Pakistan. Pakistan, along with Iran, was also heavily involved in training and arming the mujahideen.

Operation Cyclone was the name given to the operation by the CIA. According to Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, it's estimated that between 1980 and 1987, the United States spent up to $600 million a year on Operation Cyclone. And because the United States funneled the money and arms through Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, this allowed the mujahideen to "downplay the United States' role."

The Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI) mainly funded seven major Afghan mujahideen factions, "favor[ing] the most fundamentalist groups and reward[ing] them accordingly." Pakistan was also primarily involved in "training for the fighters, provid[ing] safe havens." Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia matched the financial support of the United States "dollar-for-dollar."

In an interview with Le Nouvel Observateur, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, who started Operation Cyclone, described the operation as "giving to the USSR its Vietnam war."

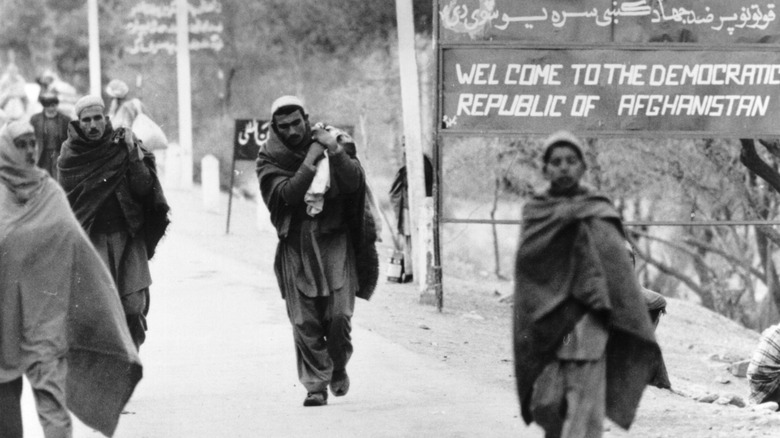

A refugee crisis

When the Soviet army finally left Afghanistan, between 15,000 and 50,000 Soviet soldiers had lost their lives during the war. But for the Afghan people, the sheer loss of life was staggering. When the Soviet army was frustrated by the mujahideen, they'd turn their weapons onto the Afghan civilians instead, Mohammed Hassan Kakar writes in "Afghanistan." But the killings also systematically targeting Afghan civilians in a genocide. It's estimated that over 1.8 million Afghans were murdered, out of whom only about 90,000 were mujahideen fighters. Up to 1.5 million people were also disabled as a result of the war.

The war also created a refugee crisis that affected up to 7.5 million people who were displaced as over 14,000 villages were destroyed, according to MEI. Out of the total refugees, 5.5 million were forced to flee the country. Most Afghan people fled to Pakistan and Iran if they were unable to find safety in Afghanistan. Over a third of the total Afghan population became refugees, and in "The Other Side of the Mountain," Jalali and Grau note that the majority haven't been able to return.

The peace accords

On April 14, 1988, the Geneva Accords were signed in order to resolve the Soviet-Afghan War. Afghanistan, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Pakistan all signed the accords after over six years of negotiations. The main point of the 1988 Geneva Accords was for the Soviet Union to pull all of its "uniformed troops" out of Afghanistan. It also stipulated for Pakistan to cease giving aid to the mujahideen. But by February 1988, Mohammed Hassan Kakar writes in "Afghanistan," the Soviets had already decided that they were going to withdraw their troops "with or without the Geneva settlement." And according to Human Rights Watch, the Reagan administration refused to accept the accords if Soviet aid to Afghanistan continued, so both nations decided to continue sending aid to Afghanistan if the other continued to do so.

The mujahideen weren't part of any of the negotiations for the Geneva Accords, and nothing was mentioned in the Geneva Accords about the future government of Afghanistan. Ultimately, the Geneva Accords did little other than "provid[e] a respectable exit for the Soviet troops."

After the Soviet withdrawal, the mujahideen continued fighting against the still-Soviet backed regime, renamed the Republic of Afghanistan in 1987, from 1989 to 1992 in the first Afghan Civil War.