How Henry Box Brown Escaped Slavery And Became An Entertainer

Henry "Box" Brown has gone down as a legendary figure of the American Anti-Slavery movement. A brave and ingenious character and a powerful campaigner, his personality and force of character emerged from his story as brightly as they did when he first told it himself to audiences on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1850s. And central to his story is the near-miraculous tale of his own daring escape from enslavement, when he cunningly got away from a plantation in Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 33. After his escape, he made it to the safety of Philadephia and into the hands of the city's growing abolitionist movement.

But as the academic Martha J. Cuttler explains, while the legend of Brown's escape may still be known to many of us today, the details of his life are not common knowledge. And according to Commonplace, little research exists to cast light on this most extraordinary of American lives. Here is what we know of the life of Henry Box Brown.

The tragic early life of Henry Box Brown

According to Martha J. Cuttler, Henry Box Brown was born in either 1815 or 1816, the child of enslaved people on a plantation in Louisa County, Virginia (per Commonplace). As Brown himself later put it, per Internet Archive: "I entered the world a slave — in the midst of a country whose most honored writings declare that all men have a right to liberty ... Yes, they robbed me of myself before I could know the nature of their wicked arts."

At the age of 15, Brown was sold to the owners of a tobacco factory in Richmond, Virginia, where he would remain enslaved for the next 18 years (per Biography). During these years, Brown got married to an enslaved woman who lived at an adjacent plantation, and the pair had at least three children. But Brown was heartbroken in 1849 when his family was sold to other slave owners in North Carolina and he never saw any of them again. "My agony was now complete," Brown later wrote. "[S]he with whom I had traveled the journey of life in chains, for the space of twelve years, and the dear little pledges God had given us I could see plainly must now be separated from me forever, and I must continue, desolate and alone, to drag my chains through the world."

Henry Box Brown escaped enslavement through the mail

Martha J. Cuttler believes that it was the loss of his young family in such heart-rending circumstances that affected a personal revolution in Henry Box Brown, Commonplace reports. Brown later said he approached his "master" in the hope that he could help prevent the same of his family. After he was refused help, he said he "had been meditating my escape from slavery ever since," per Encyclopedia Virginia.

Five months on from the loss of his family, Brown formulated an escape plan with the help of James Caesar Anthony Smith, a friend whom Brown knew from the choir at the First African Baptist Church where they both sang. According to PBS, Smith — who was Black but not enslaved — helped to convince a white sympathizer, Samuel Alexander Smith, to connect Brown to abolitionist contacts in Philadelphia.

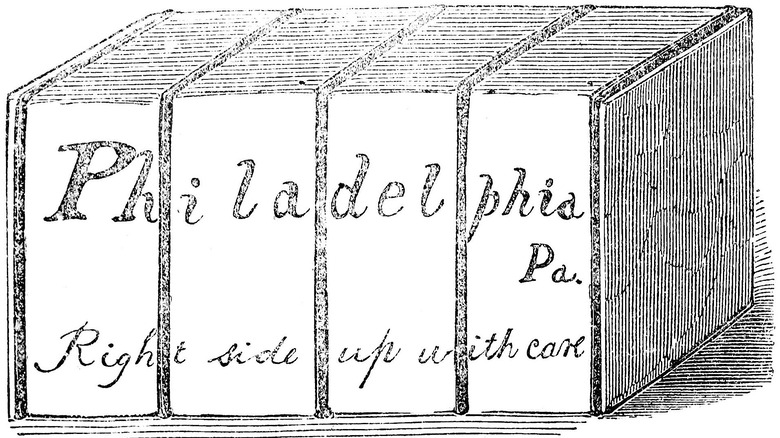

Brown began his journey on March 23, 1849, having been packed into a wooden crate, barely 3x2 feet wide, which his co-conspirators labeled "dry goods." The trip was deeply unpleasant; Brown later described the stifling conditions, while another label on the package, "this way up," was ignored by his couriers, and the escapee was regularly thrown around inside his container. The whole journey took a total of 27 long, painful hours.

Henry Box Brown found his freedom in Philadelphia

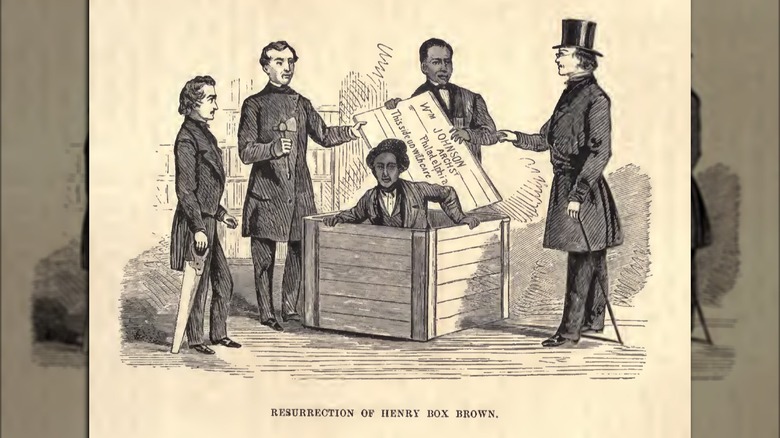

Finally, the lid of his container opened, and Henry Box Brown — who adopted the name "Box" in reference to his daring escape — found himself in Philadelphia among the abolitionists and, for the first time in his life, a free man. He had arrived at his destination: the office of a merchant and abolitionist named Passmore Williamson. Williamson was active in the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee — better known today as the Underground Railroad — which was a network that enslaved people used to escape to the free states in the north (via Commonplace).

And Brown had prepared a noteworthy entrance. Upon the lid of the box being opened, he greeted those around him with the phrase, "How you do you, gentlemen?" before breaking into a self-penned song celebrating and thanking God for his (in this case, literal) deliverance. As news spread of Brown's audacious escape, the newly freed man quickly rose to become a major celebrity of the abolitionist movement. His willingness to tell the story of his suffering — of his adventurous escape story — and to publicly decry the ongoing practice of enslavement made him a prominent and popular speaker. Indeed, crowds came out to see him throughout the free states.

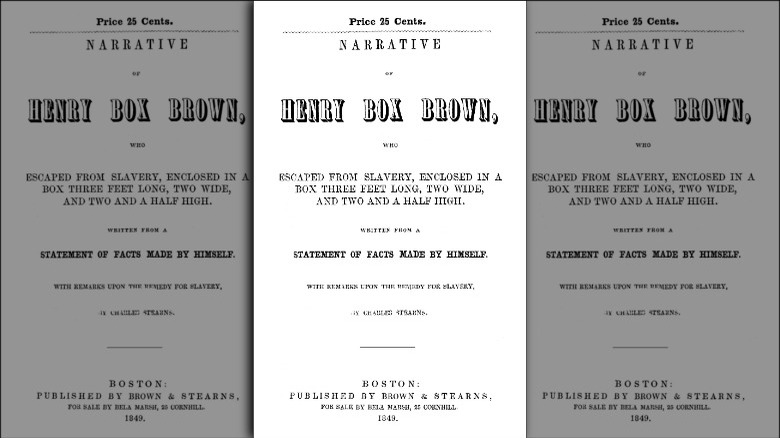

Henry Box Brown wrote a bestselling memoir

That the early tragedies and later triumphs of Henry Box Brown's life have endured along with the story of his audacious escape from enslavement is thanks to one more feat that he achieved in his incredible life. In 1849, the year that Brown secured his freedom, he collaborated with the abolitionist publisher Charles Stearns to produce "The Narrative of Henry Box Brown," which sold 8,000 copies in the first two months of publication, becoming a sell-out success (per Encyclopedia Virginia).

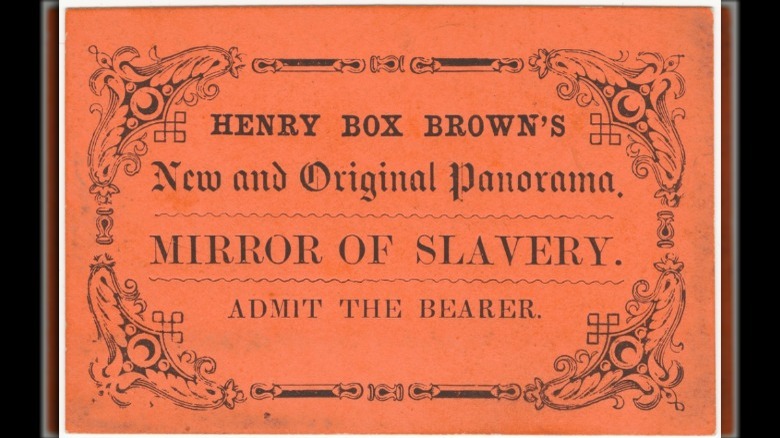

According to Virginia History, Brown used the funds from the sale of the book to build a "panorama" — a scale model that depicted numerous scenes of the conditions of enslavement in the South and of his escape. The model became a central highlight of Brown's multi-media performances and convinced his audiences of the brutal realities of slavery, which remained legal in some states until as late as 1865.

Henry Box Brown became a wildly successful performer

Martha J. Cuttler explains that following his escape, Henry Box Brown worked to establish himself as a thrilling stage performer. According to Commonplace, his shows incorporated sleight-of-hand magic, escapology, songs, and the famous panorama to tell the story of his enslavement and path to freedom. Cuttler claims there is some anecdotal evidence that Brown had learned to perform simple illusions while still a child, and that he used his skills as a magician in powerful performances to large audiences across the U.S.

But according to Biography, Brown was forced to leave the country in 1850 following the arrival of the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that the federal government locate all escaped former slaves — including those who had successfully made it to free states, just as Brown had done — and return them to enslavement. Brown fled to the U.K. where he would live, tour, and perform for the next 25 years.

Brown eventually returned to the U.S. in 1875, bringing with him an English wife and a daughter. According to Cuttler, he continued to perform, and eventually settled in Toronto, Canada, where documents reveal he worked under the title of "Professor of Animal Magnetism," suggesting that his stage show had evolved over the decades. According to Biography, Brown's final performance was in Ontario on February 26, 1889, though his final years and resting place remain a mystery.