The Messed Up Truth Of Life On A Plantation

The plantation system was first developed in the American South after it was colonized by British immigrants. Virginia specifically was divided into sections for farming on a large scale, which required people to work the land, writes National Geographic. Since the South had devised a crop-based economy for itself, plantations were inevitable. The necessity of labor led to slavery in the American colonies, though capture of Africans by the Portuguese had been occurring since the 1400s, notes Low Country Digital History Initiative.

Therefore, plantation life with slavery included was a mainstay since the start of the United States, up until the Civil War. However, slavery on plantations was terrible. Africans were first kidnapped from their homeland, then shipped on long journeys that severely killed or injured them, then were bought like chattel at slave auctions. Working on a plantation — even in the house over the fields — was more surviving than living. Though some white people cared for their slaves, that relationship was tempered by the class and status differences between owners and slaves. They couldn't forget that they were property.

After the Civil War, cotton continued to be a major Southern crop, says Mississippi Historical Society. The sharecropping system allowed freed African Americans to rent plots of land, though the landlords often maintained a strong hold over the former slaves' lives. Here are elements of the messed up life on American plantations.

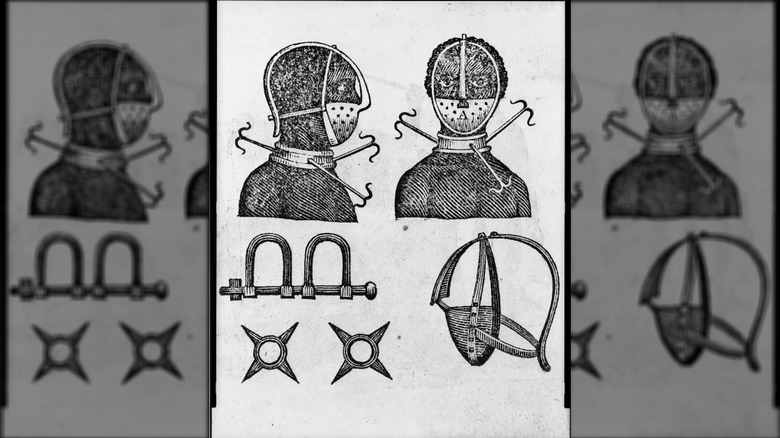

Slaves endured harsh punishments on plantations

Plantation slaves were punished for a number of infractions, including being late, not working quickly enough, and running away. They were whipped, tortured, mutilated, and worse. PBS notes that violence — real or threatened — was a tool to reinforce their property status.

It's no surprise that slaves were desperate to escape their harsh treatment, and thanks to networks such as the Underground Railroad, it's estimated that some 100,000 slaves managed to successfully flee to the North (via the Kansas City Public Library). For those not so fortunate, runaways who were caught could be whipped, shackled, and sold, among other forms of punishment.

The bell rack was one such punishment that was attached to the neck of a slave and topped with a bell that rang to alert the overseer or slave owner when a slave tried to escape (via the Library of Congress). Former slave Henry Watson recounted his experiences working on a plantation and the various punishments he endured or witnessed in his book, "Narrative of Henry Watson." "I was severely whipped with a cowskin, the scars of which punishment I have to this day, and then I was sent to the field to work ... each individual having a stated number of pounds of cotton to pick, the deficit of which was made up by as many lashes being applied to the poor slave's back as he was so unlucky as to fall short in the number of pounds of cotton which he was to have picked," he wrote. Watson went on to say that salt was often poured in the open wounds "till the blood was stanched" so the whipping could begin again.

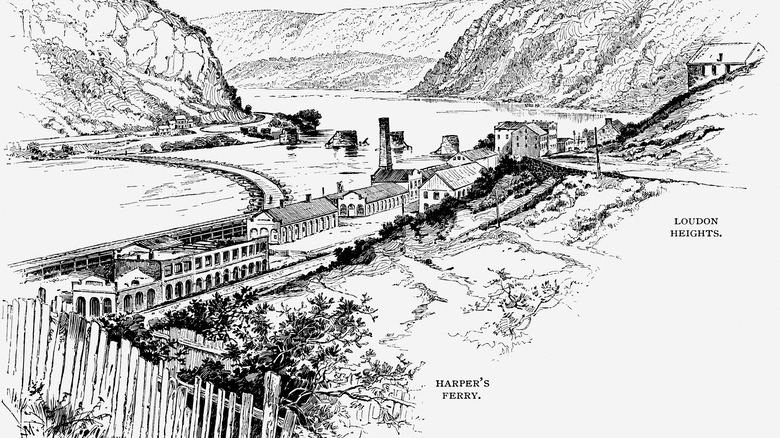

Plantation life founded slave rebellions

The most desperate form of fighting back that slaves on plantations had was the organized slave rebellion. Over 200 rebellions were discovered on American soil, many before they could be carried out. Historian Colin Palmer said about slavery, "Unconditional submission was, understandably, not easily achieved. In fact, it was an ideal that most slave owners never attained, because their often defiant chattel refused to grant it" (via National Humanities Center). Slaves planned rebellions out of a fervent desire to escape their lives of bondage by rising up against their masters.

Nat Turner, along with roughly 80 other slaves, killed 55 white people at 12 Virginia plantations in 1831, writes History. During his confession, Turner spoke about the slaves he planned the uprising with, saying, "I saluted them on coming up, and asked Will bow came be there. He answered, his life was worth no more than others, and his liberty as dear to him. I asked him if he thought to obtain it. He said he would, or lose his life. This was enough to put him in full confidence," as per his recorded "The Confessions of Nat Turner."

Slaves who were part of rebellions often did lose their lives. Despite the havoc rebellions wrecked, the consequences by white plantation owners were severe. After Turner's rebellion, legislation passed that further limited the movement, schooling, and allowance of slaves to gather in groups. Over 200 slaves who had no knowledge of Turner's rebellion were beaten by militias and mobs.

Plantation slaves -- and those who helped them -- were branded

An easy way for plantation owners to identify their own slaves was to brand them, either on the shoulder, abdomen, back, or even the face. Branding was also done as punishment, and the act was common in the South. Since the mark was intended to permanently scar the slave's body, this was yet another reminder that slaves were property, and on the same level as animals or market wares, notes Encyclopedia.

Former slave Frederick Douglass described the branding process during an 1846 lecture he delivered in England. "A person tied to a post, and his back, or such other parts was branded, laid bare; the iron was then delivered red hot, and applied to the quivering flesh, imprinting upon it the name of the monster who claimed the slave" (via Black Then).

White men who attempted to help slaves escape plantation conditions were also permanently marked. Johnathan Walker was branded in 1844 with the letters S.S. He attempted to bring Florida slaves who were part of his church to freedom in the Bahamas. He was caught and jailed for a year before the branding. The initials stood for the words "slave stealer."

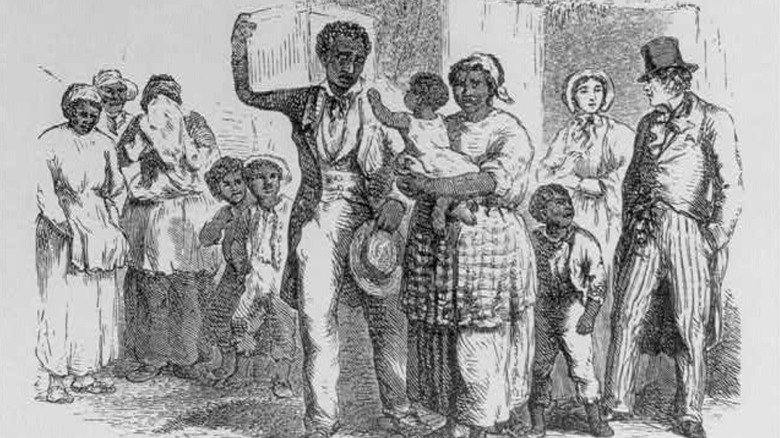

Slave families were sold away from one another

PBS notes that one of the worst conditions of enslaved life on a plantation was the constant threat of sale. Whether an owner was hard up for cash or wanted to mete out punishment, any slave, as property, could easily be sold away from their family and friends. Mothers and young children were separated; grandparents, cousins, and siblings scattered — all never to see each other again.

In March 1859, one of the largest sales of slaves in U.S. history took place in Savannah, Georgia, reports The Atlantic. Plantation owner Pierce Mease Butler (whose grandfather was one of the signers of the Constitution and author of the fugitive slave clause) sold over 430 slaves to satisfy his creditors. "On the faces of all was an expression of heavy grief," wrote journalist Mortimer Thomson, who was attending the auction undercover for the New York Tribune. "Blighted homes, crushed hopes and broken hearts, was the sad story to be read in all the anxious faces."

Slaves weren't safe on plantations due to the slave codes

Slaves were never safe, even when they were working diligently on their plantations. The slave codes were a loose set of laws that slaves endured throughout the South — and a part of why they weren't safe. Patrols of white men were organized to reinforce the rules; these men raided slave quarters and questioned slaves who were away from their plantations. In the instance of a real or even imagined insurrection, mobs of white men would come together to hunt and terrorize the Black workers.

Slaves were property and thus could not testify in a court of law, make contracts, own a gun, or buy and sell goods, among other rules. These codes were strengthened whenever there was even the rumor of a slave revolt, writes PBS. The Virginia General Assembly struck a blow to slaves in 1705 when it wrote its state's slave codes, writing (via PBS), "All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion ... shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master ... correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction ... the master shall be free of all punishment ... as if such accident never happened."

Both masters and slaves had conflicting feelings about slave drivers

Some large plantations required both a white overseer and a Black "slave driver" to keep the field workers focused on their daily tasks. Though overseers were hated, Black slave drivers received uncertain, mixed reactions from their fellow slaves, as well as the masters who hired them. Drivers were slaves in a position of power; they were both helpless and empowered, exerting authority on the very institution they were also bound.

In the 1850s, Henry and Moses were slave drivers for North Carolina plantation owner William Pettigrew. Pettigrew had to trust his slaves' capabilities; they practically ran his two plantations for him. From his letters, it's clear he had misgivings. In 1856, Pettigrew wrote to Moses (via National Humanities Center), "The people promised me to be industrious and obedient to you, you must remind them of this promise should any of them be disposed to forget it. I am anxious for your credit as well as my own that all things should go on well & it would be distressing & mortifying to me to hear the contrary on my return home."

Moses and Henry, in return, were exceedingly courteous, cognizant that their letters were going to a man who held their lives in his hands. Henry replied, "I return my respects to you. I was glad to hear from master. I have don all day in my power towards your benefit. I was glad to hear that master is in good health..."

Southern weather created health problems

The heat and humid weather of the South caused numerous health issues, notes PBS. Working in the rice plantations during the summer was worse than picking cotton, as it meant slaves standing in water under a sweltering sun for hours at a time. Malaria was very common, as was infant death. Staying indoors and hoping it would be cooler wasn't an option for field slaves who had to work in the sweltering sun for hours on end.

In 1826, Philip Tidyman, a South Carolina physician and planter, argued that, essentially, slaves were "protected by the very nature of his constitution from the unhealthiness of hot climates, which are so inimical to the whites, especially among those who may be necessitated to labour in low swampy situations," writes an article in the American Journal of Public Health. That same article quotes South Carolinian Charles Pinckney warning, "wherever the principal sources of national wealth — Cotton, Rice and Sugar — flourish, it is physically impossible for a white man to cultivate them; those who merely superintend the labors of the blacks are poorly compensated for the risk of health and life."

MIT notes that the climate and geography in the South providing a breeding ground for malaria and other parasitic diseases, with severe consequences like "low birth weights, high neonatal and infant mortality, stunted slave children, and the effects of protein deficiency."

Women were abused and exploited

Slave women were exploited by the white men around them. Harriet Jacobs' 1861 narrative, "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl," tells the reader that when she was around 14 years old, her master, his sons, or the overseer (or possibly all of them) began to give her gifts in hopes of sexual favors. When she refused, she was beaten and starved, in hopes that would force her to submit, according to J. M. Allain's "Sexual Relations Between Elite White Women and Enslaved Men in the Antebellum South: A Socio-Historical Analysis." And Jacobs' account is only one example.

Women had no recourse against assault, sexual favors, or being a long-term concubine to a white slave owner, as in the case of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson. There were no safeguards or a safe way out, and white men took all the advantages they could get. There were also sexual relationships between slave men and white women, though those were rarer. White women may have been trying to exert their own power in whatever way they could, since their husbands and fathers held the real power in their lives.

According to the National Humanities Center's article, "On Slaveholders' Sexual Abuse of Slaves," sexual abuse could extend to forced relationships between two slaves who were considered "good breeders." Their children would then be sold away from their parents for the sake of making a tidy profit.

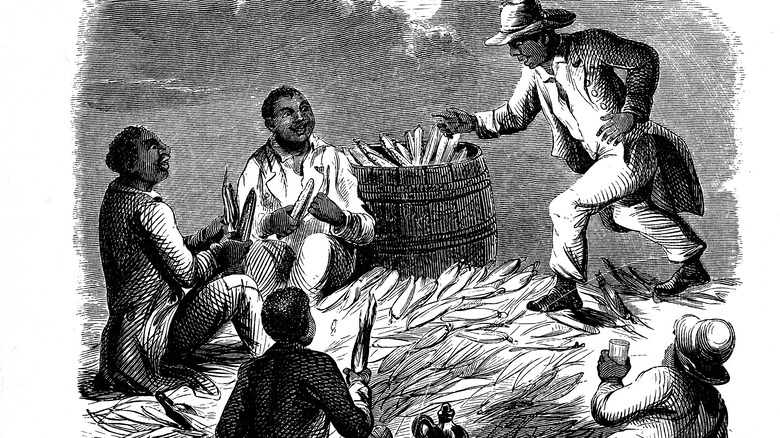

Working on a plantation was backbreaking labor

Slaves on sugar plantations in the Caribbean had a hard time of it, since growing and processing sugarcane was backbreaking work that killed many. New slaves were constantly brought in each year to replace those who had died. By the time a slave was 40, having worked since their teen years, they would appear to be near the end of their life, writes The Saint Laurentia Project.

Sugarcane was popular in Britain and America, and the laborers had to perform every step of the process themselves. Slaves grew the crop, separated the sugar juice from the cane, and treated it to create molasses. The waste was turned into rum, which was done in the Caribbean, as well as parts of Louisiana and Mississippi. The process of planting the sugarcane was particularly grueling, involving digging hundreds of holes in the ground each day. On large plantations, slaves worked 24 hour days for six days of the week at harvest time.

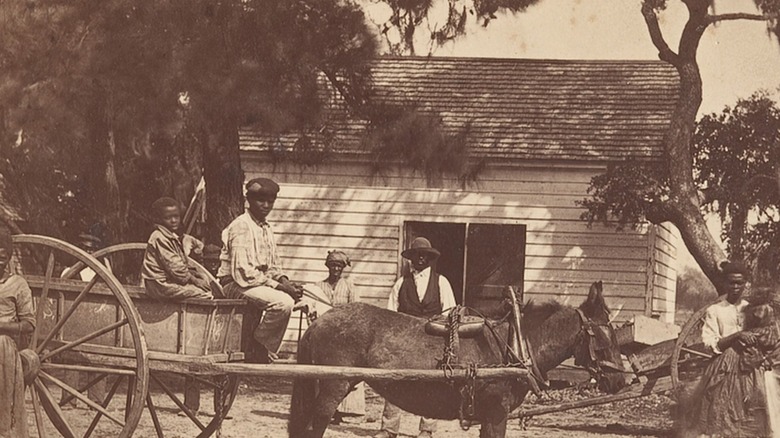

Many slaves who lived in the lower South worked on cotton plantations. Some plantations raised more than one crop, including tobacco, rice, corn, and sugarcane, writes PBS. Plantations and farms required plenty of other physical labor not necessarily related to planting and harvesting, such as digging ditches and clearing fresh land.

The class system between plantation slaves caused division

There was a caste system on plantations among slaves, dividing who worked in the house and who worked in the fields. Field work was excruciating but also didn't involve dealing with white owners as house slaves did.

Though working the fields was exhausting, house slave Lewis Clarke understood that serving in the house was not the best option either, writing (via Spartacus Educational), "There were four house-slaves in this family, including myself, and though we had not, in all respects, so hard work as the field hands, yet in many things our condition was much worse. We were constantly exposed to the whims and passions of every member of the family; from the least to the greatest their anger was wreaked upon us."

Thirteen notes things that often differentiated domestics from the field workers, such as clothing and attitude. House slaves were better dressed than field slaves, who were usually not given enough clothes except in the winter months. House slaves, by contrast, might be dressed in old castoffs from their white owners. Field workers found a sense of companionship together, while house slaves, working alone, might be swayed to their masters' interpretation over the slaves.

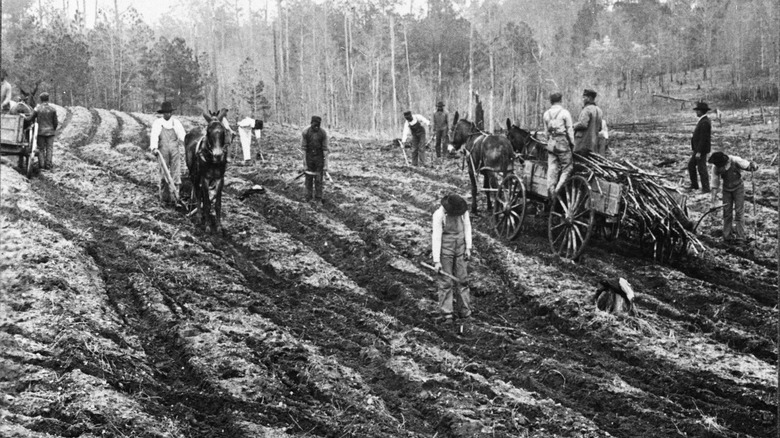

Reconstruction-era sharecropping wasn't the boon everyone hoped for

Though they were free after the Civil War, the new sharecropping system kept many African-Americans in poverty and even in debt to the white landowners they rented from. Similar to slavery, the debt, as well as laws favoring landowners, kept them tied to the land, unable to leave for better opportunities, writes PBS.

Plantation owners needed workers to recapture their failed economy, and African Americans needed to make a living. This meant that they were able to rent out land from white owners, but otherwise live their own lives. The beginning of a sharecroppers contract from 1867 reads (via Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History): "... the said Cooper Hughs Freedman with his wife and one other woman, and the said Charles Roberts with his wife Hannah and one boy are to work on said farm and to cultivate forty acres in corn and twenty acres in cotton ..."

However, very few free Blacks became landowners, writes Digital History. Unfair landlords, high interest rates, and unpredictable harvests kept African Americans downtrodden, particularly since debt was carried over from one year to the next.