Most Dangerous Animals In The Americas

It's nice to think of the modern, 21st century world as a place where we have a lot of conveniences that make the place safer than it was, say, a few hundred years ago. Humankind has an existence padded with things like vaccines, an in-depth knowledge of the do's and don'ts of basic nutrition, and clean water... for now. It's easy to forget just how good people have it today — there's no more hunting mammoths for food, or drinking water downstream from a dysentery-ridden camp on the Oregon Trail.

That's not to say our world is completely safe, though, because as soon as humans think they sort of got things under control, that's when nature says, "Hold my beer."

Nature is an unthinkably powerful force, and it's one to be reckoned with. It's worth noting that humans aren't the only violent, dangerous creatures that roam the planet's surface, and simply put, when it comes to some of these animals of the Americas, soft and squishy humans just don't stand a chance.

Home to the most poisonous animal in the world

There's no denying that the tropical rain forests of Central and South America are breathtaking, but anyone making their way through the jungle needs to be very careful: The entire area from Costa Rica down into Brazil is the stomping ground of the most poisonous animal in the world. That's the brightly-colored poison dart frog, and according to National Geographic, the tiny frog — which is about the same size as a paperclip — was so named because the area's indigenous population once used the frogs' poison on the end of their blowgun darts. The process of safely harvesting the poison isn't for the squeamish: the BBC says after the frogs were caught, they would be impaled via a stick down the throat, which would cause them to start sweating poison.

It's unclear just how the frogs synthesize the poison, but they make a lot — a single frog can kill 10 adult men. Even the babies are deadly, because the frogs — who incidentally make excellent, caring, and attentive parents — feed their young with their own unfertilized eggs, giving them an early dose of the deadly stuff.

They've been protecting themselves with deadly force for around 40 million years, and anyone who takes a bite out of them can't say they weren't warned. Studies from the East Carolina University in Greenville confirmed that the brighter the color, the more deadly the poison, which tends to kill by paralyzing the victim, both internally and externally.

Are rattlesnakes as dangerous as we think?

Healthline says rattlesnake bites aren't the sort of thing you can just shake off, as the snakes produce a venom that can destroy tissue, cause severe internal hemorrhaging, and do some serious damage to a person's circulatory system. Ideally, victims should be treated within half an hour, and the timeline for organ failure and death is about a max of three days. Even with treatment, research shows that some can suffer strokes, kidney failure, and the partial loss of organs like intestines.

That said, here's a bit of good news. The Los Angeles Times says that while the US logs an average of 7,500 people bitten by rattlesnakes every year, only about five of those cases are deadly... but the side effects are getting more deadly as the years progress, so maybe not roll the dice on this one. When rattlesnakes bite, it turns out that they don't always release their venom, especially into humans. But here's a very important footnote: Rattlesnakes that have been decapitated can still bite for around an hour after they're killed.

In 2018, a Texas man named Jeremy Sutcliffe beheaded a snake that was threatening his wife. Ten minutes later, it bit him. The Washington Post says he suffered internal bleeding, septic shock, and organ failure. It took 26 doses of antivenin to stabilize him, and experts added that being bitten by a decapitated rattlesnake head was "very common."

This is your pet what-now?

It sounds like one of those insane statistics that just can't be true, but according to the Humane Society of the United States, there are somewhere between 5,000 and 7,000 tigers in the US at any given time. No one's even really sure how many there are, as laws forcing owners to register tigers often don't exist and aren't enforced. It's also super easy to get a tiger: the World Wildlife Fund says (via The Guardian), "In some states, it is easier to buy a tiger than to adopt a dog from a local animal shelter."

That said... please don't adopt a tiger. There are more tigers living in the US in captivity than there are left in the wild, and the questionable ethics of making a tiger live in a cage aside, there's a whole slew of incidents that show why it's a terrible idea. National Geographic conservation biologist Imogene Cancellare sums it up like this: "These are animals whose brains are literally designed to be ambush predators. There is no scenario in which entering a [space] with a big cat is going to be 100% safe, even if it's been hand-raised."

And most of them are, thanks to a phenomenon called "speed-breeding," where tiger owners force the breeding of cubs for tourists to pet. When they're too big, they're culled — and that's exactly what GW Exotic Animal Park was investigated for doing in 2012, after 23 tiger cubs died between 2009 and 2010.

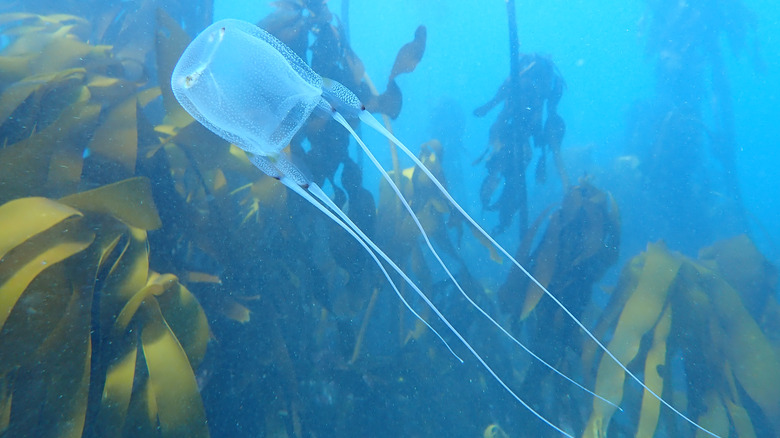

The most dangerous jellyfish in Australia

The National Ocean Service says that the most dangerous jellyfish in the world is the box jellyfish. There are a few different varieties of these beautiful yet deadly creatures, and while they're usually found in the waters around Australia and the Indo-Pacific, here's the thing: they're also one of the few jellyfish that swim instead of simply floating.

And yes, they've absolutely headed to the coastal waters of the Americas. In 2020, Newsweek reported that a beach in Hawaii was closed after 30 people were stung when jellyfish showed up, and they also noted that the phenomenon wasn't as unusual as people might hope. They're also pretty common in areas of Florida: In 2012, the Smithsonian reported that Caribbean box jellyfish had spread and made Boca Raton their new home. It was described as "another symptom of a changing world," so that's fun.

American Oceans says there's about 50 different kinds of box jellyfish, and while they're not all dangerous, those that are, well, they're really dangerous. The Irukandji is about 100 times more toxic than a cobra, and the Sea Wasp can kill 60 people with just one of the half a million or so darts that line the seemingly delicate-looking tentacles. What happens after the sting isn't pleasant. It depends on the jellyfish, but most symptoms include things like shock, paralysis, and cardiac arrest. A changing world, indeed.

Bambi's revenge

Deer might be incredible to watch, but they're also incredibly deadly. That's according to the Insurance Information Institute, which says that between 1975 to the mid-2000s, the number of deer-related road accidents was on the rise. And here's the thing: Defenders of Wildlife says that about 2% of those collisions involving a car and a deer turn deadly, but when it's a collision between a deer and a motorcycle, there's a fatality 85% of the time.

In some states, there's a high likelihood of having an accident. In West Virginia, it's a 1 in 37 chance, and in Montana, it's a 1 in 47 chance. In 2018, 190 people died in deer-related collisions, and that number is remaining pretty steady. Accidents peak between October and December (via IIHS), which coincides not only with deer mating season, but something humans are responsible for — hunting season.

Deer on their own aren't that dangerous, so what's made them so deadly? When LCB compiled the data, they found that there were several things that contributed. With the growth of cities and towns, people were pushing deer out of their native habitats and making them compete for space and food — which often led them onto and across the street. Deer populations have gotten so out of control that some areas resort to culling huge numbers of the animals, and The Washington Post says there's another problem. With fewer and fewer people hunting, population control has become a serious problem.

Do killer bees live up to their name?

The Scientist says that when Warwick Kerr, a Brazilian entomologist, died in 2018, the Amazonian city of Manaus held an official three-day mourning period. Which sounds odd, because he invented killer bees.

Kerr, says IFLScience, was trying to hybridize bees that would be able to work efficiently in Brazil's hot, muggy climate. He crossed European bees with African bees, and when they escaped to kill hundreds of people, he didn't shy away from the fact that he felt responsible — and he tried to fix it.

But according to the Natural History Museum, the cat was already out of the bag, so-to-speak. They moved up from Brazil, through Central America, and reached the US by 1990, and they're pretty terrifying. That comes not because an individual bee is more deadly than their unhybridized counterparts, but because they're wildly aggressive. They defend their nests en masse, with swarms of up to 800,000 bees having been reported. Every sting releases a pheromone that tells other bees to sting, and it takes about 1,000 to kill a person — likely someone that was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. Africanized bees often mistake vibrations — like cars — for threats, and attack. There's good news, though: In some places, like Puerto Rico, subsequent generations are slowly becoming not-so-aggressive. Instead, they're slowly starting to do exactly what Kerr wanted, and are working away in hot, humid climates.

Please don't feed the wildlife, and this is why

Moose are so downright goofy-looking, it's tough to see them as anything but cartoonish. Seeing one in person should be on anyone's bucket list, but Popular Science says that everyone should remember it shouldn't involve getting up close and personal. Moose attacks outnumber grizzly and black bear attacks combined, and that's for a few reasons. Alaska Zoo director Pat Lampi says he's heard all kinds of stories about people doing all kinds of dumb things, from letting their dogs off the leash to give chase to throwing snowballs at a moose, to thinking it's a great idea to try to feed one.

None of those things should ever be done. Moose can react to being surprised or threatened by charging, and given that they can run at 35 mph and hit like a freight train... don't surprise or threaten them. Females with young moose will react to threats accordingly, and male moose during mating season, well, Lampi says: "That's when they lose their minds. They'll fight with anything that crosses their path: another moose, a swing set, Christmas lights, anything."

And don't think moose attacks only happen in the wilderness, either. In 2021, a woman was walking a dog down the street of Glenwood Springs, Colorado, when she was attacked by a female moose thought to be protecting her calves. NBC noted that she was in no way to blame, and that living in moose territory simply comes with risks.

The deadliest animal in the world

The animal that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls "the World's Deadliest Animal" is also one of the most annoying, and it's the mosquito. It's a global problem, and they say that of the planet's 3 billion people, about 40% are at risk of contracting the mosquito-borne dengue fever. That's just one disease. The American Mosquito Control Association says that around a million people die each and every year thanks to these annoying little pests, and when it comes to things like malaria, it was a huge problem in the US up until the 1940s.

What about today? There's been more than 350,000 cases of Chikungunya in the Americas since the beginning of 2014, including a strain that thrives in the southern US. Heartworm is a major problem that pet owners need to prevent in their furry family members, outbreaks of dengue fever — with thousands of victims — happen pretty regularly, and yellow fever pops up occasionally, too. There's a whole bunch of different kinds of encephalitis that mosquitoes carry, and let's not forget about West Nile virus and Zika, either.

Mosquitoes have been around in the Americas from about 100 million years ago, and that's a lot of time to annoy — and kill — a lot of creatures, so would it be a bad thing if they went the way of the dodo? Entomologists generally say (via the BBC) yes, because we could end up with something much worse in their place.

Beautiful and deadly

Esteban Payán is the director of Colombia's arm of Panthera, an organization dedicated to encouraging people and big cats to live together peacefully. He says (via the Natural Resources Defense Council) that while jaguars typically don't attack people if they're left alone, the relentless onward march of the human population across the globe has brought them into closer and closer contact with people — sometimes, with devastating consequences.

In 2012, Panthera was asked to go over a case study where a jaguar bit one man, left, but later killed two others. They came to the conclusion that once the big cat realized with the first bite that humans were potential prey, she not only killed again, but brought her cubs along to teach them that people, too, were viable targets. All three jaguars ended up being killed, a move that Panthera supported. Payán explained: "You can't risk another human life when you're dealing with that," and there's a bit more to it.

Not only are they smart, but according to Discover Wildlife, they have the most powerful bite of any of the big cats — in relation to their size. Panthera CEO Alan Rabinowitz says (via National Geographic) that impacts how the jaguar hunts — not by going for the throat, but by crushing the skull. "I've actually seen where they've lifted the cranial cap off large animals, like a large tapir or a cow. It's the most incredible means of killing — terrifying and very, very fast."

Maybe this is a little bit of revenge?

Otters may be cute, with all their hand-holding and cuddling, but no human wants to meet one in the wild. Really. Otter attacks are pretty terrifying. A Montana woman needed stitches after being attacked by one in 2013, while it was an 8-year-old and his grandmother who were on the receiving end of otter wrath in 2014. Both were hospitalized, and the boy nearly died. Two teenagers were swimming in a California reservoir when they were attacked in 2017 (via the Independent), and several Floridan kayakers were attacked within days of each other in 2018 (via Fox 13). And so on, and so on.

University of Redlands biology professor Lei Lani Stelle says (via Outside) that while otters will usually go out of their way to avoid people, the problems come when individual otters contract rabies: According to a study from IUCN Otter Spec. Group, about 66% of attacks involve a rabid otter.

Things also go sideways when people wander into their territory — especially when there's babies around. And that's been happening more than most might expect. Otters were once widespread throughout North America before being extensively hunted for their pelts. Then, the growth of cities pushed people and otters even closer together, and for some, the results have been bloody.

The prehistoric monsters of the Americas

Crocodiles look like dinosaurs, and there's a good reason for that — they were doing their slow saunter across the land 200 million years ago, and Nova says they haven't really changed much in the meantime.

Experts from Charles Darwin University and RIEL say that across the globe, crocodiles kill around 1,000 people every year — and that includes stats from the Americas. The American crocodile is found throughout tropical areas in southern Florida, but National Geographic says they're also found across Central America and down into the northernmost reaches of South America. But there's another player in the game, too: National Geographic also says that worldwide, American crocs and alligators killed 33 people between 2000 and 2016... while 286 people were killed by Nile crocodiles.

Four of these super-aggressive, extra-murdery were found in Florida, and while Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Sciences' croc expert Adam Rosenblatt says we probably don't need to stress too much about these invaders, "we do need to take this seriously." Especially since Nile crocs — which can be longer than a giraffe is tall — make 15-foot-long American crocs look like children's toys.

Climate change is making the north much more dangerous

The consequences of climate change are unfolding across the globe in ridiculously devastating ways, and some areas are feeling the pressure more than others. The World Wildlife Fund says that as the polar ice caps continue to melt, that's going to force polar bears farther and farther from their natural habitat. That, in turn, is going to bring them into increasingly close contact with the people living in the northern reaches of the Americas, and it's already happening.

In fall of 2014, the town of Arviat — part of the Canadian Arctic — spent nights trying to keep three polar bears from getting too close. US Fish and Wildlife Service polar bear expert Jim Wilder explained (via Alaska Public Media): "When they have less opportunity to hunt... the bears become thinner, skinnier. ... when polar bears become thinner and skinnier, they become a little more aggressive in their pursuit of feeding opportunities."

The Smithsonian says that Wales, Alaska has even established the Kingikmiut Nanuuq Patrol — which translates to the Wales polar bear patrol. They're trained to run polar bears out of town before attacks can happen, because they definitely can. Research from Yale has found that polar bear attacks are happening more and more often, and most come during the months when there's the least amount of sea ice. That's historically been between July and December, but what happens when it's a year-around problem?

As if venom isn't enough...

University of Florida Health says that stonefish are found in tropical waters around the world, and that includes waters off Florida, and in the Caribbean. Their venom is ridiculously toxic, and getting stung means a world of hurt — along with a list of symptoms like difficulty breathing, bleeding, abdominal pain, shock, seizures, numbness, and in what's perhaps the most understated symptom of all: "No heartbeat." The best case scenario is getting stung in an extremity, making it to the hospital, and getting treatment for symptoms that are still going to last a week or two. Worst case? The victim is just a goner.

As if the toxicity isn't bad enough, University of Kansas researchers found that the fish — which can blend in with their surroundings so well that you don't know they're there until you step on one — also come equipped with something called a "lachrymal saber." In layman's terms: A switchblade in their heads.

Ali Francis stepped on one while vacationing in Barbados, and wrote (via The Guardian) that the near-death experience was enough to make her rethink all of her life choices. In the throes of excruciating pain, she was told by a local that it "probably" wouldn't kill her... and that's not super reassuring, is it?

The most successful hunter in the world

Let's talk about a different kind of dangerous — the animal that's the biggest danger not necessarily to humans, but to prey. It might seem like the best hunter in the world might be a big cat, but according to the BBC, that's not the case at all. When it comes to successful kills, it's a creature most Americans have in their backyard: the dragonfly. While big cats have an estimated success rate of one in seven or — according to some studies — one in 20, dragonflies are successful 95% of the time.

These little creatures are built to be killing machines. In addition to wings that are controlled by a complex series of muscles for unparalleled agility, they also have eyes designed to spot prey against the bright sky, and the ability to not just chase their prey like other predators but to predict movements. That allows them to get ahead of their prey and wait for it to come to them, instead of following along behind.

Dragonflies are pretty darn cool. The Smithsonian says that they evolved around 300 million years ago, and once grew to have a wingspan of a whopping two feet. While it's a given that they're much smaller now, they're still a major player when it comes to controlling the population of another deadly animal: the mosquito. Each dragonfly can eat hundreds of mosquitoes in a day, and that just goes to show that "dangerous" isn't always a bad thing.

The high cost of milk production

When it comes to cows, Heifer International knows what they're talking about — and they say that there's around 20 people who are killed by cows each year in just the United States. There are two major culprits: females that have just given birth, and males that just exist. Homestead on the Range shares some eye-opening information, including the fact that dairy bulls are much more dangerous and likely to attack. They're so dangerous, in fact, that dairy farmers who choose to keep a bull around typically kill them when they're only a few years old, or "before he has an opportunity to develop a bad attitude."

There's a few factors at work here. Dairy cows are often hand-raised by people in order to get the most milk out of mom and onto the shelf. But a consequence of that is that they don't necessarily learn to differentiate between cows and people, or respect the latter. Dairy bulls are often kept away from the others in order to manage breeding and birthing seasons, and a lonely bull is a mad bull.

Stories of lifelong farmers being attacked and gored by their own animals are terrifying. Farm and Dairy told the story of Judy Ligo, a farmer who bred and sold Highland cows. She had a hand-reared bull named Bandit, and he gave a snort, then charged her. He tossed her around a bit before she escaped, and she ended up with broken ribs and a broken neck.

Do not do a Google image search for sand fleas

There's a lot of nasty creatures that live in the sand, but here's the thing: There's sand fleas, and then there's the sand flea called Tunga penetrans. The CDC says these little nightmares are commonly found on tropical beaches, and that includes along the shores of the Caribbean, Mexico, Central, and South America.

When they first bite, they cause just sort of a general itch. That's just the start of things, though, as that's when the sand flea burrows deep under the skin. Health says it's the females that are the biggest problem, as they'll eat their way into an appendage — usually a foot — and then after mating and laying her eggs, she'll usually fall out. Most of the time.

What happens next is a high likelihood of bacterial infection, the development of lesions, ulcers, and in extreme cases, it's not unheard of to have that all followed up with full-blown gangrene, amputation, or tetanus. The World Health Organization says it's called Tungiasis, and it happens because not only is there a flea head buried under the skin, but in order to feed her babies, the female flea drinks blood and grows to around 2,000 times her original size and destroys the tissue around her. Treated, it can have long-lasting impacts, and untreated, it can absolutely be deadly.

It may be little, but it has a big bite

The Mayo Clinic says that of the 1,500 different types of scorpions, there's only about 30 that pose any danger to humans — and the most dangerous of all of those is the bark scorpion, which is native to the southwestern United States.

The bark scorpion is one of the few scorpions that actually produces enough venom to kill a person, with children being most at risk of death or severe symptoms, which can include loss of control over movements, high blood pressure, a fast heart rate, uncontrollable crying, drooling, sweating, and vomiting. New Mexico State University says stings in extremities can lead to paralysis that usually lasts no more than 72 hours, but here's some good news: They also confirm that they glow in the dark, so at least they're easy to see at night, which is when they're out hunting.

Fun fact: Bark scorpions are armed and ready to go almost from the day they come into the world. Texas A&M says that baby scorpions become completely independent at about 2 weeks old, and it's also worth noting that different species of bark scorpion come with different levels of danger. Texas bark scorpions, for example, have a relatively mild neurotoxin, so... that's about as good as a sentence with the word "neurotoxin" can be.

How dangerous are piranhas... really?

So there's no way to talk about the dangerous animals of the Americas without mentioning piranhas. But are they actually man-eating monsters? The Smithsonian says that in 1913, Teddy Roosevelt headed down to South America, and saw one in action. He reported: "They will snap a finger off a hand, ... they mutilate swimmers — in every river town in Paraguay there are men who have been thus mutilated; they will rend and devour alive any wounded man or beast..."

But will they really, though? It turns out that locals had known Roosevelt was coming and captured — then starved — some piranhas ahead of time. So of course, when they threw them back into a river with a dead cow, they went nuts. The official experts say that most piranhas exist quite happily on a diet of worms, seeds, other fish, and insects, and some are even completely vegetarian. Who would have thought?

Piranhas can, however, still zoom in on a single drop of blood in 52 gallons of water, and while there is one piranha that might live up to the lore, it's still not quite the monster it's portrayed as in countless pop culture references. The red-bellied piranha is known to attack swimmers, but that's typically only when they feel they're being threatened. They'll also attack if food is scarce, if their eggs are threatened, and they'll definitely lash out if they're caught in a fisherman's net or on a hook. But honestly, who wouldn't?