The Mythology Of Cronos Explained

There is a lot going on when it comes to Greek mythology. And that's definitely something of an understatement. There are just so many stories, and so many different versions of the stories — some of which even manage to contradict each other, because that's just how things go with tales from thousands of years ago that have been told and retold for generations.

So, for now, let's start at the beginning. Or sort of near the beginning, at least. Everyone's heard of the main group of Olympian gods — Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Hades — but where did they all come from? Well, you can hop back a generation to their parents, the Titans Rhea and Cronos, the latter of which has quite a few stories of his own, like his rise and fall from power, defeating the sky itself only to be thrown down to the deepest pits of the Underworld by his own family. And while there might not be quite as many stories about Cronos as there are about his famous offspring, there's still a whole long narrative that he's pretty central to. Maybe you're heard of it, or maybe you haven't, but either way, how does a dive into Greek myth sound?

Cronos overthrew his father

"Overthrowing fathers" is a bit of a trend with this whole section of Greek mythology, and Cronos is kind of the one who starts it.

Cronos — and the rest of the Titans — were born to Gaia (the Earth) and Ouranos (the Sky, sometimes spelled as Uranus, like the planet). But the Titans weren't the only kids born to Gaia and Ouranos; the full list also includes the Cyclopes, and another race called the Hecatoncheires, per ThoughtCo. Unfortunately for all parties involved, Ouranos was jealous of his children, and so, according to Greek Mythology, he forced Gaia to keep all of them imprisoned in her womb. (Hesiod's "Theogony" says that he specifically hid the Hecatoncheires — giant beings with a hundred arms and 50 heads — but suffice to say, regardless of which version of the myth you're reading, Ouranos wasn't a great father).

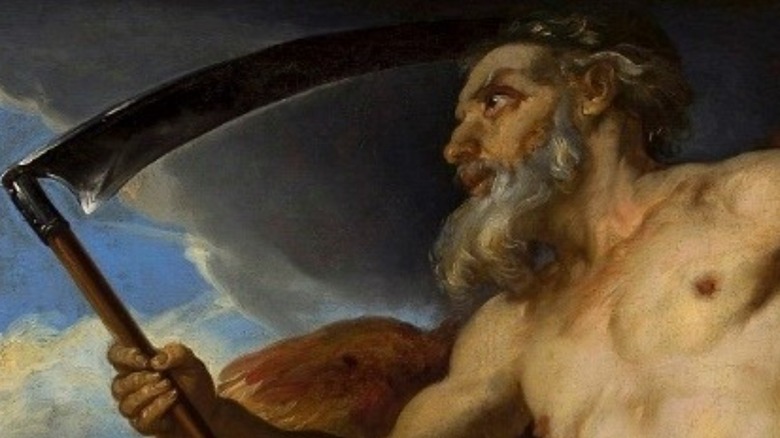

Naturally, Gaia wasn't pleased by the way things were going and the somewhat tyrannical nature of her husband, so she called for her children to rise up and punish their father. Given that their father was the literal heavens, most of them weren't exactly rushing to take up the task, as "Theogony" explains (via Theoi Project). Except for Cronos, the youngest and most ambitious, who was perfectly willing to take up his mother's flint sickle and castrate his father, placing himself on the throne as the king of the Titans.

Cronos' rule during the Golden Age of Humanity

One of the aspects of Greek mythology is the idea that human history can be separated into five different eras, (almost) all named after metals: gold, silver, bronze, heroic, and iron (via Theoi Project). There are entire stories around that mythology, but the part that matters here is the fact that Cronos was the ruler of the world during the Golden Era, and, despite his vilification further down the line, his rule during this age was said to be the high point of human existence.

After the fall of Ouranos, Gaia finally felt free, producing a bunch of crops and resources for humans, without them needing to do a single thing, per Greek Mythology. Without the struggle to survive, humanity flourished. Hesiod said in his "Works and Days" that humans lived almost like the gods. There was no such thing as grief, everything was provided for them, the weather was perfect, and age didn't affect them. Seriously, old age didn't slow down anyone in this era, and even though they did die from it, it was never a painful death. It was always a peaceful one, with dying being just as easy as sleep.

Plato later went on to attribute all of this directly to Cronos himself, saying that his decision to appoint a superior race of spirits to reign allowed for this utopia to exist. (By contrast, Plato doesn't seem all too impressed by Zeus' reign over the earth).

Cronos cannibalized (almost) all of his kids

With Cronos overthrowing his tyrannical father, it seemed that history was just about ready to repeat himself. As Ovid said, at some point after becoming king of the Titans, Cronos received some not-so-great news: "Best of kings, you shall be knocked from power by a son" (via Theoi Project). Now, as the king of the world, what would you do with that information other than turn incredibly paranoid and start making bad decisions?

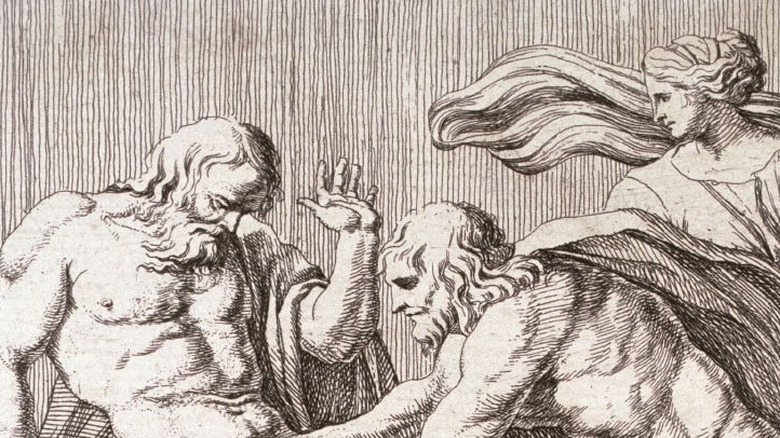

Obviously, Cronos couldn't risk losing his position of power, so when his wife (also sister) Rhea started to give birth to their kids, what was a paranoid ruler to do? Well, eat his kids, of course! The story generally goes the same way as it's told on Britannica: he swallowed all of his kids — the Olympian Gods Hestia, Demeter, Hades, Poseidon, and Hera — whole. (He also imprisoned the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires, just to be extra safe). Rhea wasn't really happy with what was happening, and while she was pregnant with Zeus, she sought out help from her parents (Gaia and Ouranos) for help. The "Theogony" explains that she was allowed to give birth to Zeus on Crete; from there Gaia helped to hide him away from his father. So what did Cronos get instead? A rock, swaddled in cloth to look like a child, which he swallowed, completely unaware that he hadn't, in fact, killed his own son.

Cronos' level of paranoia varies by myth

In general, the myth of Cronos swallowing his children goes the way that Hesiod tells it in his "Theogony." Cronos ate each of his children, as well as a rock in place of Zeus who was hidden away by his mother (via Theoi Project).

Funnily enough, though, that's not actually the only version of the myth out there (Greek mythology is truly wild, and there are tons of different versions of stories, depending on what you're reading). For example, if you felt like reading Pausanias' "Description of Greece," then you'd find out that, in some versions of the myth, Zeus wasn't the only one who was saved. Rather, Rhea also managed to save Poseidon, leaving him in a pasture, surrounded by a flock of lambs. When she returned to Cronos, she told him that she'd given birth to a horse, so he accepted a foal as his son (which he subsequently ate. Of course).

Or there's Pseudo-Hyginus and the "Fabulae," which says that Cronos (Saturnus, in this version, since it's a Roman telling) didn't eat any of his children. Rather, he threw Orcus (Hades) into Tartarus and Neptunus (Poseidon) into the sea. But since he knew it was a son who would overthrow him, he left, at least, Juno (Hera) alone and alive. She was the one who actually asked for Jove (Zeus) from her mother, raising him on Crete until he was old enough to overthrow their father.

Zeus would be Cronos' undoing

With Cronos having, essentially, no idea that one of his children had actually survived his feast (of sorts), that leaves us with the perfect set-up for an epic showdown, doesn't it?

Pseudo-Apollodorus' account in the "Bibliotheca" explains that Zeus was born on Mount Dicte, where "the armed Louretes stood guard over him in the cave, banging their spears against their shields to prevent Cronos from hearing the infant's voice" (via Theoi Project). There, he was kept safe, with some myths saying he was fed and nursed by the goat Amalthea, and others adding in a bunch of other beings (like nymphs) who somehow played a part in raising the child (like bathing him).

Point being: Cronos had no idea Zeus was being raised to overthrow him, just as the prophecy had predicted, and, according to Greek Mythology, it didn't really take too much in the end. Once he was fully grown, Zeus dressed as one of his father's cupbearers as a means of infiltration, but instead of carrying wine, he bore a concoction brewed by Metis. The brew was a vomit-inducing drink of some kind, and you can probably see where this is going. Cronos vomited up all of his children — that group of Olympian Gods — and from there, the real conflict got going.

The Titanomachy ended with Cronos sent to Tartarus

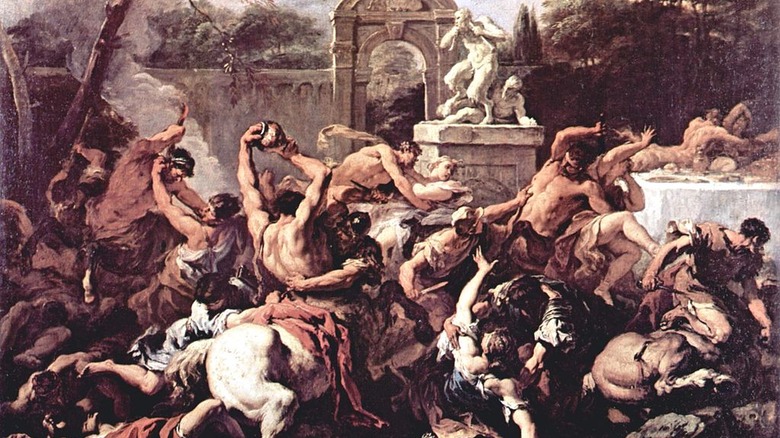

With Zeus and his siblings back in action, Cronos had a pretty big problem on his hands. You know, the kind of problem that ends up resulting in a war: the Titanomachy.

After Zeus returned and rescued his siblings, 10 years of fighting broke out between the Titans and the Olympians, according to Classical Literature. In "Theogony," Hesiod says that Zeus also reached out to the rest of the Titans, promising them power and privilege that Cronos hadn't allowed them (via Theoi Project) — long story short, it worked, the Titans Prometheus and Epimetheus fighting alongside the Olympians. What really turned the tide of battle, though, was the Olympians again making allies of those Cronos had spurned — namely the Cyclopes and the Hecatoncheires. Cronos had imprisoned them after taking power, but Zeus freed both groups, and Pseudo-Apollodorus' "Bibliotheca" adds that it was actually the Cyclopes who provided some of the most iconic symbols in Greek mythology: Zeus' thunderbolt, Poseidon's trident, and Hades' helm. With the help, the Olympians were able to overpower the Titans, and Zeus was said to have wrestled his father for the throne, ultimately throwing all of his enemies down into the deepest pits of Tartarus.

That said, the story didn't fully end there. Gaia tried to get revenge for the defeat of the Titans, giving birth to a horrific monster — Typhoeus — but it'll suffice to say that the Olympians still came out on top.

Cronos became the king of Elysium

Going through the whole story of Cronos, it seems like it would be fitting if there was no happy ending. Strangely enough, though, that's not really how things went. Greek mythology has its own version of the afterlife, with the worst of humanity being sent off for eternal punishment in Tartarus, and the best getting to reside in Elysium, or the Isles of the Blessed (via Theoi Project). Elysium was nothing less than paradise, the lands producing sweet fruit and beautiful flowers without anyone needing to lift a finger, and it became the resting place of a bunch of famous Greek heroes, like Peleus, Cadmus, and Achilles, just to name a few.

The Heroic era saw lots of humans gaining access into Elysium, but with Zeus in charge of the universe, it was getting harder to actually check who was coming and going. Unworthy folk were sneaking their way in, and the gods couldn't have that, appointing judges, but doing a bit more than that, too.

That's where Cronos comes in. The details aren't really elaborated on, but after being trapped in Tartarus for a while, Cronos was released from his bonds and made into the ruler of Elysium. He was, effectively, made into a king once again, with his own people working beneath him and presiding over the most honorable of the dead. It was basically a return to glory for him.

In some stories, Cronos escaped to Rome

Let's step away from Cronos for a second and take a look at his Roman counterpart (Saturn), because while Greek and Roman mythology are pretty similar, there is a difference between the two when it comes to Cronos.

See, the Romans, in general, saw Saturn in a much more positive light than the Greeks saw Cronos. To them, he was their wise old god of agriculture. As for why he took on that role, well, the story goes that, after being defeated by Zeus (or, technically, Jove in this case, because we've got the Roman versions of everyone here), Saturn fled to the region called Latium — better known as the future location of Rome — and settled there, per World History Encyclopedia. He even founded his own town — with the very on-the-nose name of Saturnalia — which he proceeded to lead. During his time as its ruler, he was said to teach the people of Saturnalia farming and agriculture in general (hence why he's so heavily tied to the practice in Roman mythology), helping them to become more civilized.

According to GreekMythology.com, his rule was another Golden Age for humanity, albeit only in Rome, which led the Romans to celebrate him with his own festival, the Saturnalia (depicted in the art above). It was the most important holiday to the Romans and was celebrated in December (and, thus, it might've played a part in influencing Christmas celebrations in the future).

Cronos created Chiron and Aphrodite, too

So, you might be thinking that saying Cronos "created" Chiron and Aphrodite is a weird turn of phrase, but there's a reason for it, don't worry.

The story surrounding Chiron — the centaur known for training a bunch of Greek heroes, like Heracles and Achilles — is more or less what you'd expect. At some point during his rule over the Earth, Cronos, well, cheated on his wife. The exact details vary by story, but Cronos — potentially while on the hunt for Zeus — ended up crossing paths with Philyra, daughter of Oceanus (via Theoi Project). He might have shown up in the form of a horse, or he might have turned into a horse to flee after Rhea discovered his tryst with Philyra. Either way, Philyra gave birth to the centaur Chiron because, you know, Cronos was a horse at some point during their interaction.

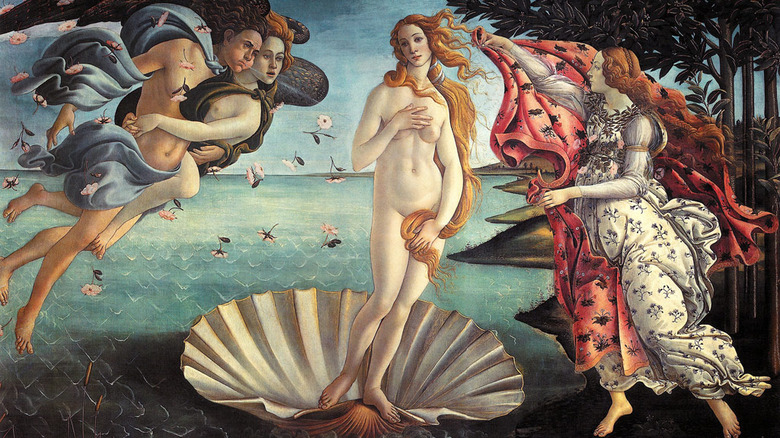

Aphrodite is a very different case. She's considered one of the Olympian Gods but doesn't share the same parentage (being the kids or grandkids of Cronos). Instead, she just appeared out of the sea foam — think "The Birth of Venus" (shown above), since it's that whole story. As for why, well, that's where Cronos comes in. He castrated his father, Ouranos, and that's how he became the king of the Titans. Per Britannica, doing that then involved tossing his father's severed genitals into the ocean, that's where the sea foam that created Aphrodite actually came from.

Cronos cursed Zeus to suffer the same fate he had

So, you know how there was that fun trend of sons overthrowing their fathers in this particular narrative? Cronos overthrew his father Ouranos, and then Zeus overthrew Cronos — that whole deal. Well, funnily enough, there's the possibility that the trend didn't stop there. Aeschylus made mention of it in the tragedy "Prometheus Bound." After being dethroned, Cronos saw to it that his son would, one day, suffer the exact same fate he had — being deposed by his child — and lay a curse on Zeus to ensure that it would come true (via Theoi Project). He wanted his son to experience all of the things that he had: the feeling of being so thoroughly humbled (but not, you know, in a good way) and falling so completely from grace.

Fortunately for him, Zeus had already been planning a marriage with the goddess Thetis (who would later be the mother of the hero, Achilles), and Cronos' curse would make this child into a powerful warrior, one who would "discover a flame mightier than the lightning... a prodigy who shall shiver the trident, Poseidon's spear."

But Zeus would manage to avoid that fate, with Prometheus warning him away from the marriage before any of that would come to pass. (Poseidon also avoided the same fate, according to Britannica, both he and Zeus having been given the same warning about Thetis from the goddess of justice, Themis).

Cronos, or Chronos?

Let's talk names for just a second, because the names in Greek mythology are a little bit of a mess. Or, maybe more than a little bit, to be honest.

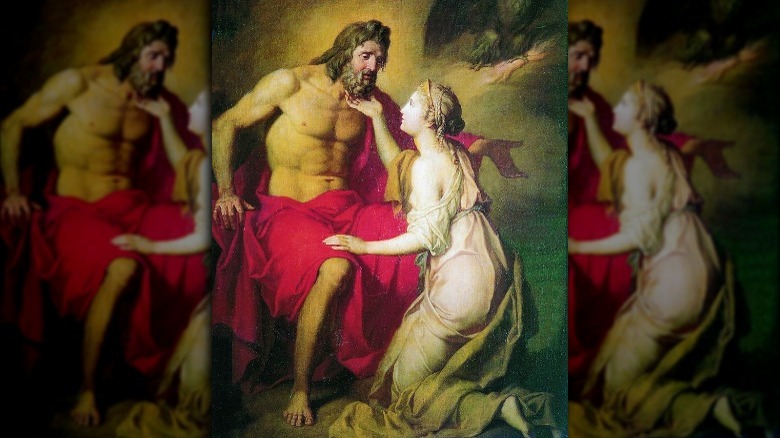

Cronos (or Cronus, or Kronos, or one of a couple other different spellings, depending on what you're reading) was one of the 12 Titans, often depicted as an old, bearded man with a walking stick, per ThoughtCo. Greek Mythology also adds that he was pretty often seen as "Old Father Time," which is sort of where a lot of the confusion comes from. You see, the Greek word for — and personification of — time was actually "chronos," which sounds essentially the same. And to make things more confusing, the Greeks themselves actually identified Cronos with the Phoenician god of time, El Olam.

Eventually, Cronos and Chronos just became more and more conflated with each other. The two of them looked physically similar in art, and Cronos was often depicted with some kind of a timepiece, and all of his actions were associated with the effects of time. His cannibalism of his kids became tied to the destructiveness of time, while his rule during the Golden Age or over Elysium became more associated with the "passing of the ages," as it's said on Theoi Project. By the time of the Renaissance, the two were effectively indistinguishable, leaving us with the portrayal of Cronos that we have today.