The Untold History Of Vaccine Passports

As of the end of August 2021, over 5 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been given out worldwide. However, most of these doses have been administered in wealthy, Western countries, and even when countries are able to provide vaccines to their residents, these vaccines aren't deemed to be good enough.

Associated Press reports that in the summer of 2021, the European Union decided that those who'd been vaccinated with AstraZeneca that was manufactured in India aren't sufficiently vaccinated. And while some countries have independently decided to allow people with "non-EU-endorsed vaccines" to enter, others maintain the ban.

What does this mean in a world where vaccine passports are necessary to travel? Will people be required to get multiple brands of vaccines just to travel? And how does this compare to the history of vaccine passports? This isn't the first time that documentation has been used for both medical and travel purposes and while it certainly won't be the last, the framework for the COVID-19 global vaccination passport will likely set the tone for future global travel requirements.

Certificates of health

Some of the earliest examples of a vaccine passport come just after the Black Death decimated the populations of Africa, Asia, and Europe. And although the certificates have changed throughout history, their basic components of ensuring the authenticity of bearer and authority have remained consistent since the 15th century, according to the Science History Institute.

But during the Black Death, the health passes did little other than underscore the idea that the person didn't show any symptoms, rather than ensuring that a person wasn't contagious. Initially handwritten, with the proliferation of the printing press, the health certificates became a little more standardized, with individual information being filled into pre-printed forms. And during times of travel restrictions, exemptions would even be printed. Ultimately, these documents were more about signifying that a person was "exempt from government controls."

According to ORIGINS, unfortunately, these certificates weren't always as valid as they appeared, even if they were received from an authority figure. When the plague hit London in 1665, health passes were handed out to the Lord Mayor to anyone who was well-connected and wished to leave the city, "handing them out to "all those who lived in the ninety-seven parishes," Daniel Defoe writes in "A Journal of the Plague Year."

Smallpox vaccination certificates

One of the earliest discussions involving a proof of vaccination started in India, then known as the British Raj, in regard to both smallpox and the plague. According to NPR, after Waldemar Haffkine developed a vaccine for the plague in 1897 and the vaccine started being used in India, Hindu and Muslim pilgrimage sites were designated by authorities as places that required proof of vaccination for pilgrims.

This occurred soon after the Compulsory Vaccination Act was passed in India in 1892, per the Indian Journal of Medical Research, to encourage smallpox vaccination. And before long, smallpox vaccination certificates were required to board ships for those traveling to Great Britain or Mecca from South Asia if there was an outbreak.

Smallpox vaccination certificates were also issued in Denmark as early as 1885, per the Danish Museum, and in the Ottoman Empire by 1903, per the Erciyes Medical Journal.

And as soon as there were vaccination certificates, forgeries came into existence. In 1904, The New York Times reported that there was "extensive traffic in worthless certificates of sufficient vaccination by east side physicians." And these certificates weren't just for traveling overseas. Many schools in the United States required for children to show a smallpox vaccination certificate before they were allowed to attend and in New Zealand, Māori were required to show a certificate in order to travel by train.

Targeting people crossing borders

Vaccination certificates and health passes also have a long history of being used as a type of border control and an added layer of harassment against migrants. In 1916, the United States started requiring day workers from Mexico to undergo "disinfection" at the border, claiming that workers were bringing typhus to the United States, a claim that was entirely unsubstantiated. More than one fumigation facility was built on the border, even after 26 imprisoned Mexican workers and two Americans burned to death at a disinfection facility.

The disinfection involved nothing more than being strip-searched and being sprayed with gasoline and insecticide and was often used to humiliate Mexican workers crossing the border. Afterward, a certificate was issued, but this certificate was only valid for one week, per Mexico Unexplained.

Carmelita Torres was responsible for starting the 1917 Bath Riots in her protest against the humiliating treatment, but unfortunately, the riots had little lasting effect. The mandatory gas baths and their respective certificates continued into the 1960s, with kerosene being replaced by DDR powder dusting in the 1940s, René Kladzyk writes in "The Gas Baths."

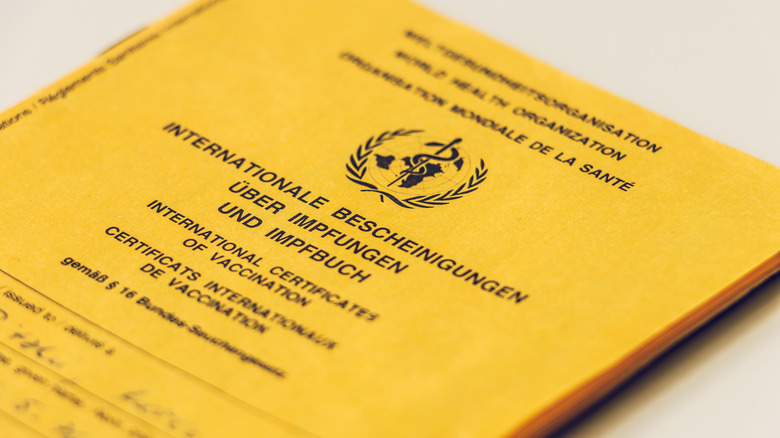

Current International Health Regulations

Since 1969, the World Health Organization has been issuing what's known as a "yellow card," which is used to show proof of vaccination for yellow fever and other diseases. And according to NPR, without proof of a yellow fever vaccination, countries have the right to refuse entry as specified in the International Health Regulations.

But depending on the country, vaccine recommendations can be made to travelers. For example, when traveling to Pakistan, as of April 2021 WHO recommends getting a single adult dose of the polio vaccine. However, these recommendations aren't considered a "blanket rule."

In the case of COVID-19, there have never before been any efforts to create global certification. And considering the fact that many people have yet to get even one dose of the vaccine while others have already gotten two. According to Jen Kates, senior vice president and director of Global Health & HIV Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, "A certification now could exacerbate inequities for such things as employment in other countries for people not yet vaccinated."