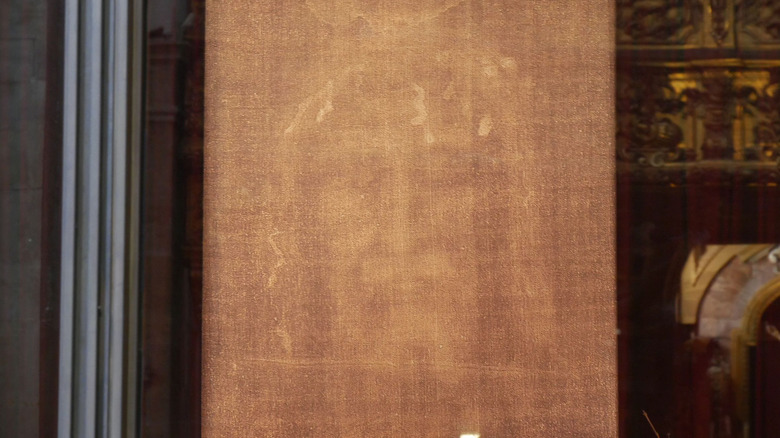

Does The Shroud Of Turin Actually Have Jesus' Name On It?

For about 700 years now, the ecclesiastical and scientific communities have been at odds over a piece of linen cloth. However, the Shroud of Turin, or "Holy Shroud" as it's also known, is no ordinary piece of cloth. Believers claim that the shroud, which appears to depict a negative image of a man who was tortured and killed in the same way that Jesus of Nazareth was, is Christ's actual burial cloth, his image somehow burned into it, as Chemistry World reports. Skeptics, however, point to radiocarbon dating, carried out in the 1980s, that placed its origin squarely in the Middle Ages, thus making it a medieval forgery. Further, according to Oxford University, believers claim those tests were flawed or inconclusive, but those challenges have been refuted. The Catholic Church, for whatever it's worth, has refused to take a stand on its veracity, according to Catholic Straight Answers.

Controversy about the shroud's origins erupted again when a Vatican researcher claimed that bits of writing on the cloth included the name of Jesus rendered in Ancient Greek, thus proving that the shroud truly was and is Christ's burial cloth. It's not an explanation that held any water with skeptics, and to this day the shroud's authenticity remains a matter of debate.

Did someone risk their life to forge Jesus' name on the shroud?

Vatican researcher Barbara Frale published a book in which she claimed that, via computer enhancements of faint markings on the shroud, she could see letters written in Greek, Latin and Aramaic scattered about. According to an Associated Press story posted at Phys.org, she concluded that among those words were "(J)esu(s) Nazarene" — Jesus of Nazareth in Greek. If you're a shroud skeptic, it's easy to conclude that whoever forged the cloth simply took the time to forge the writing on it as well. However, Frale claimed that if anyone did that in the Middle Ages, they'd have done so to their peril. That's because, as she sees it, to mention Jesus without mentioning his divinity, even when propagating a hoax, could have led to the person doing so being branded a heretic. "Even someone intent on forging a relic would have had all the reasons to place the signs of divinity on this object. Had we found 'Christ' or the 'Son of God' we could have considered it a hoax, or a devotional inscription," she said.

However, church historian Antonio Lombatti chalks up the letters to wishful thinking. "People work on grainy photos and think they see things. It's all the result of imagination and computer software. ... there are no letters," he said.