The C.S. Lewis And J.R.R. Tolkien Relationship Explained

On the topic of friendship, C.S. Lewis said it best: "Friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself ... It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival" as reported by Brain Pickings. This passage from his book "The Four Loves" was inspired, at least in part, by Lewis' celebrated friendship with fellow author and English professor J.R.R. Tolkien (pictured).

It's no exaggeration to claim that both authors would have never reached the zenith of their literary potential without this friendship (via Literary Traveler). Yet, the relationship proved highly complicated and not without controversies. Unfortunately, these problems would eventually get the better of both men, souring their camaraderie and pulling them apart. They spent the last decade of their lives separated by unspoken resentments and a buildup of passive-aggressive feelings.

How could such an epic friendship later turn so bad? Keep reading as we break down the C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien relationship.

J.R.R. Tolkien led C.S. Lewis to Christianity

One of the most famous discussions in literary history occurred on the night of September 20, 1931 (via The Gospel Coalition). It involved three professors — C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Hugo Dyson — at the University of Oxford near Magdalen College's Addison's Walk. Had the discussion gone differently, the repercussions for English literature would have proven incalculable. Tolkien and Lewis had yet to write their greatest works. And Lewis would never have blossomed into one of the greatest Christian apologists.

What happened during the conversation? Lewis expressed deep dissatisfaction with his belief in materialism and atheism, according to Eric Metaxas. But Tolkien pointed Lewis beyond the confines of tangible reality. He argued that more profound truths lay within the world's great mythologies, from the Greeks to the Romans and the Norse. Chief among these? The greatest myth of all — Jesus Christ. The key difference between Jesus and other myths? Jesus' story was both tangible and true.

Tolkien asked Lewis why materialism and atheism should lead to such sadness were these concepts true? And he wanted to know why and how humans developed the concept of the Divine if it had no basis in reality? Tolkien drove his point home by asking Lewis "to consider whether it was possible that one time this myth had coincided with history — whether one time eternity might have broken through into time." This thought proved too captivating for Lewis to ignore.

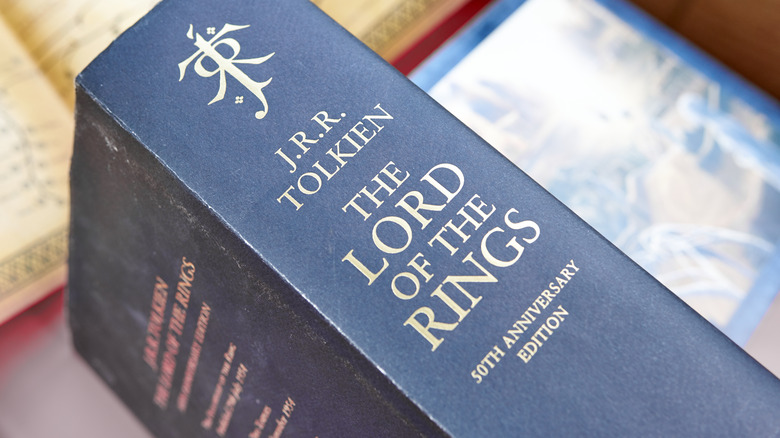

C.S. Lewis encouraged J.R.R. Tolkien to write 'The Lord of the Rings'

Four years into their friendship, the literary duo were members of the Inklings, a literary society created for the love of ancient tales of heroes and gods, as reported by Newsweek. The group met up to share each other's writing and to workshop new ideas and manuscripts.

When J.R.R. Tolkien shared an early draft of one of the stories that would figure prominently in his Middle Earth saga with Lewis, he received consistent encouragement. Tolkien would later admit that without C.S. Lewis' encouragement, he never would've finished the books. As Tolkien later confided to Dick Plotz, "Only from [Lewis] did I ever get the idea that my 'stuff' could be more than a private hobby. But for his interest and unceasing eagerness for more I should never have brought [it] to a conclusion" (via Good Reads).

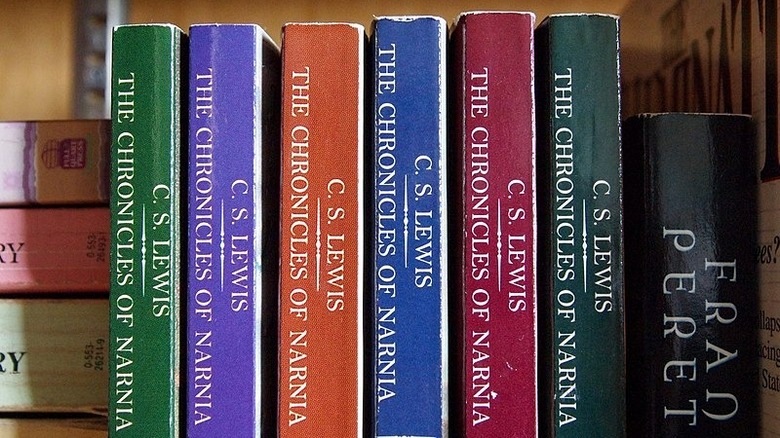

Conversely, Lewis' literary work proved forever influenced by Tolkien, according to Eric Metaxas. After the garden stroll, Lewis converted to Christianity. But his newfound inspiration didn't stop there. He started weaving Christian themes into his writings, setting the stage for "The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" and many other works (via The Christian Broadcasting Network).

They bonded over their experiences in WWI

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien (pictured) experienced the horrors of war firsthand in the trenches of the Great War (via the C.S. Lewis Institute). Both men served as second lieutenants and lost their closest friends in combat. The Great War left deep scars that would follow these men throughout their lives. Lewis would later report suffering from troubling dreams about the war for years after his service had ended.

Yet, despite the horrors that both men faced, they didn't give in to the natural inclination of so many contemporaries. Instead of writing bitter, cynical, or absurd novels, they remained idealistic. Unlike other members of the "Lost Generation" who spent their words rejecting time-honored concepts such as heroism and virtue, Tolkien and Lewis borrowed heavily from the great epic stories of the past. Instead of crumbling beneath spiritual rot, their wartime experiences shaped their spirituality in profound ways.

According to the C.S. Lewis Institute, "In the stories of Tolkien and Lewis, there is this very important idea about our responsibility to resist evil and choose to do the right thing, even when it looks very risky. This is what heroes do." Both men learned these lessons while on the battlefields of France during the so-called "War to End All Wars." And these lessons and their response to them comprised the mortar that deeply bonded them, according to the Literary Traveler.

C.S. Lewis wanted to 'smack' J.R.R. Tolkien

When J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis (pictured) met for the first time in 1926, Lewis proved far from impressed by his new colleague (via Newsweek). They met at a Merton College English Faculty Meeting, and he would later note in his diary that Tolkien looked like a "smooth, pale, fluent little chap" who "only needs a smack or so."

Of course, poor first impressions aside, the men had far too much in common not to become best mates. After all, they existed in a sort of "isolation from the mainstream of intellectual culture." They felt like outsiders regarding their interests, literary pursuits, and worldviews. Despite being WWI veterans, they didn't fit the mold of the "Lost Generation."

What's more, their profound spirituality contrasted heartily with a world increasingly oriented towards agnosticism and even full-on atheism, especially in the academic sphere. Because both writers felt increasingly alienated by the changing world around them, it made them cling even more closely to their "escapist" tendencies as well as their friendship, according to Literary Traveler.

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien helped bridge the gap between literature and linguistics

Although both men served as English faculty, they occupied very different roles at the college, according to the Literary Traveler. C.S. Lewis remained firmly embedded in the literature faction while J.R.R. Tolkien stuck strictly to linguistics and the history of languages. Tolkien took his fascination with all things medieval to such an extreme that he refused to read any works written after the Middle Ages. In other words, no Charles Dickens, no Bronte sisters, and no Thomas Hardy.

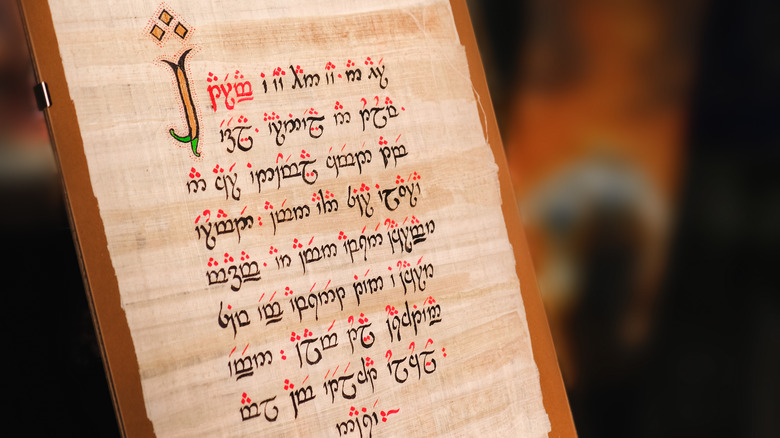

Yet their friendship endured despite the radical schism in their academic preferences. Even more surprisingly, instead of causing a civil war within the English department, Lewis and Tolkien forged a pioneering bridge between both departmental factions. To these ends, they revised the English Department syllabus, making both study pathways richer for the effort. Despite synthesizing these disparate study paths through their friendship, Tolkien remained obsessed with constructed languages throughout his life, according to Babbel.

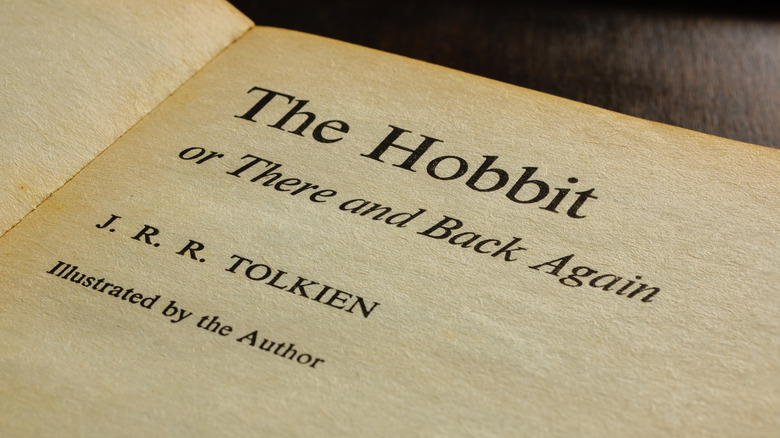

To further his Lord of the Rings trilogy, he invented expansive languages and histories to accompany them, including various dialects of Elvish and Dwarvish. Creating these languages represented a labor of love designed for a "linguistic aesthetic" in his works. A veritable language genius, Tolkien described his fascination as a "secret vice," as reported by CNRS News. Yet, in an ironic twist, Tolkien ultimately satiated his linguistic obsession through the vehicle of literature.

They both lost their parents as children

C.S. Lewis' mother, Flora Lewis, died of cancer when he was nine years old, and his bereaved father sent him to boarding school, effectively abandoning him (via A Pilgrim in Narnia). Years later, Lewis would describe the fallout from this event: "With my mother's death all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared from my life." Themes of abandonment (both voluntary and involuntary) prevail in his literary works, where the absence of parental figures remains palpable. From the Pevensie children to Prince Caspian and Eustace Scrubb, these characters must operate in a world without benevolent authority figures.

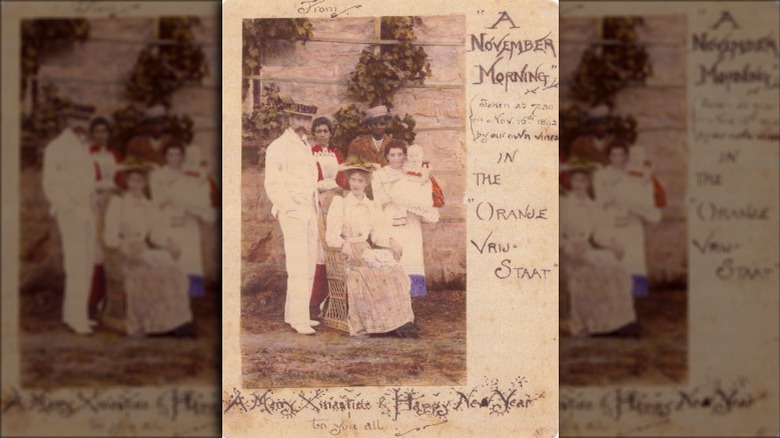

Common ground existed between Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien when it came to familial circumstances, according to the Tolkien Society. Born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, on January 3, 1892, Tolkien retained few memories of his African home apart from a giant, hairy spider that would later turn up (along with its friends) in The Hobbit trilogy. His father suffered a severe hemorrhage and died on February 15, 1896.

His mother, Mabel, chose to return to the familiar: her family in West Midlands, United Kingdom. Yet, by 1904, she faced death, diagnosed with diabetes, which proved almost always fatal before the discovery of insulin. This left Tolkien and his brother wards of the family's parish priest, Father Francis Morgan, according to Britannica. Like Lewis, he would make many of his main characters either orphans or semi-orphans, like Frodo, whose parents died when he was 12 (via Mega Interesting).

J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis pursued escapism through their writings

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien both rejected aspects of modern life (via the C.S. Lewis Institute). They used their love of folklore and mythology to escape from an increasingly frenetic and technology-dominated reality. As both men dove deeply into fantasy and sci-fi realms, they found a dearth of fantastic fiction. So, they pulled a Toni Morrison.

Remember when Morrison said, "If there's a book you really want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it?" (via Goodreads). That's precisely what C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien did (via the Literary Traveler). They wove into fiction the stories they most wanted to read. Their colleagues would accuse them of escapism, especially Tolkien. But that's too simplistic an appraisal of their work. After all, their fictional worlds contained plenty of drama and trouble, too. But the authors still appear to have found solace, nonetheless, in anachronistic settings liberated from the technologies (and problems) of the present age.

As reported by NPR, Dr. Alan Jacobs argues Lewis and Tolkien "were convinced that they were two oddball weirdos who cared about stories that nobody else cared about, who were interested in periods of literary history that no one else was interested in." And it's not hard to see how they came to this conclusion in a literary world dominated by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and e.e. cummings (via Family Search).

Both men enjoyed legendary love affairs

C.S. Lewis and his wife Joy Davidman had a storied romance cut short by her cancer diagnosis and death in 1960, as reported by The Guardian. Letters by Lewis detail the profoundness of his grief and the deep and abiding love he would always feel for her. Their real-life love story would become the basis for the critically acclaimed movie "Shadowlands."

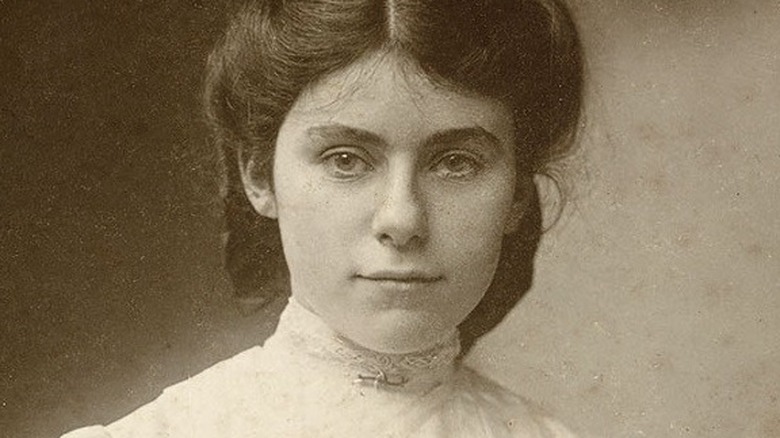

In "A Grief Observed," Lewis expresses both the depths of his sorrow and the fullness of the esteem he felt for his late wife, a poet in her own right. He would write of Davidman, "Her mind was lithe and quick and muscular as a leopard ... I was never less silly than as [Joy's] lover" (via Lit Hub). According to Refinery 29, J.R.R. Tolkien enjoyed an equally passionate love affair with his wife, Edith (pictured). The two met as teenagers living in a boarding house. At 19, Edith was three years Tolkien's senior, yet they fell head over heels for each other.

Tolkien's guardian disapproved of his ward's relationship with Edith, the illegitimate daughter of a Protestant governess. Father Francis forbade Tolkien from corresponding with her until he turned 21. By then, she was engaged to another man, as reported by Mental Floss. Yet, they rekindled their romance; she left her fiancé, converted to Catholicism, and married Tolkien. The film "Tolkien" brings this epic romance to life, showing how Edith became the muse for her husband's most famous heroines, including Luthien (via Entertainment Weekly).

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien received different receptions during their lifetimes

During the 1930s and the 1940s, C.S. Lewis published extensively, earning the esteem of his colleagues and the public. According to the Literary Traveler, "Oxford quickly embraced him as a literary and religious celebrity." Soon, he had speaking engagements across the nation, and his books flew off shelves, as reported by his official website.

But things looked quite different for Lewis' friend and colleague, J.R.R. Tolkien. He could have gone the route of a dour linguistics academic, celebrated by his colleagues. Indeed, published academic works such as his translation of "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" garnered him the appropriate attention. So did his essay on "Beowulf." But his creative ambitions wouldn't allow him to remain pigeonholed as a professor of linguistics. For this, his professional reputation paid the price.

It's easy to forget today that Tolkien's work was once received with derision. His colleagues joked with him about his fantasies and mockingly asked him, "How is your hobbit?" Nevertheless, Lewis encouraged Tolkien to put pen to paper, turning his daydreams into something material.

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien held 'Beowulf and Beer' sessions

Yes, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were academics, but they also knew how to have a good time. During "Beowulf and Beer" sessions, they discussed the hero's journey and the worlds each spun in their imaginations (via the Literary Traveler). By November 1931, Lewis noted in a letter to his brother, "It has become a regular custom that Tolkien should drop in on me of a Monday morning and drink a glass," as reported in A Pilgrim in Narnia. This Monday morning routine eventually evolved into author gatherings.

Where did they host these meetups? According to Newsweek, none other than the Rabbit Room, located at The Eagle and Child, on St. Giles Street at Oxford's campus. (They cheekily called it the "Bird and the Baby.") The men's regular drinking spot also proved an ideal meeting location for their literary association, the Inklings. Were the "Beowulf and Beer" sessions and meetings of the Inklings the height of nerdiness? Most assuredly. But these events provided fertile ground for authors in the prime of their writing careers.

The friendships forged during these events would also see reflection in the works of each author. Lewis went by the nickname "Jack," and he liked to refer to Tolkien as "Tollers." He dedicated an entire chapter of his book "The Four Loves" to friendship. And, more particularly, his friendship with Tolkien. What's more, both men emphasized "the importance of friendship in the struggle against evil" (via the C.S. Lewis Institute).

Their friendship hit lows over writing difference and religion

Despite the abiding friendship that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien cultivated, rivalries and disagreements marred the relationship over time, according to the Literary Traveler. From the genres they chose to their writing styles, the men didn't see eye to eye. What's more, they clashed over their authorial methods and even how fast they produced new work.

Over time, these small arguments magnified. Lewis complained about Tolkien's obsessive perfectionism and inability to accept advice from anybody else. He would write of Tolkien, "His standard of self-criticism was high, and the mere suggestion of publication usually set him upon a revision." Yet, Lewis still admired Tolkien's stories and enthusiastically supported his colleague. Without Lewis' robust encouragement, it's hard to imagine Tolkien ever publishing his work.

But Tolkien failed to reciprocate these feelings for Lewis' work. When Lewis first read a draft of "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" aloud to the Inklings, "Tolkien was horrified," as reported by NPR. "He thought it was a terrible book," namely because of the mishmash of myths and legends. Tolkien also disapproved of Lewis' personal life, including his marriage to Joy Davidson (an American divorcee), writes Colin Duriez in "Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: A Gift of Friendship."

According to Mental Floss, "Their relationship cooled over what Tolkien perceived as Lewis' anti-Catholic leanings and scandalous personal life." As Duriez notes, they never truly regained their closeness, even after Lewis' wife died of cancer in 1960. Their fell out of contact with one another, and their meetings became sporadic.

A fellowship of writers never broken

One of the most incredible and influential literary relationships of all time ended with rather bittersweet. Involving two of the 20th century's most celebrated authors, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, this friendship left indelible impressions on English literature. Yet, what appeared to be an unshakeable camaraderie had waned. Why? Because of petty disagreements and unspoken resentments.

According to Tolkien's letters, by the time C.S. Lewis died from kidney failure on November 22, 1963, the two literary had been estranged for a few years. As Colin Duriez writes in "Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship," the two hadn't been very close for nearly a decade, only sharing pleasentries through the occasional letter. And it was only within a few weeks prior to Lewis' death that Tolkien had visited is sick friend on his deathbed.

However, Tolkien attended Lewis' funeral and in a letter penned to his daughter, Priscilla, expressed profound grief. Tolkien would write, "This feels like an axe-blow near the roots. Very sad that we should have been so separated in the last years: but our time of close communion endured in memory for both of us."

Despite the blemish at the end of their relationship, the shock waves of their friendship still resound today. After all, it's no exaggeration to attribute their greatest literary works to the encouragement they showed one another (via Newsweek). And their friendship would transcend time. How? Through their many literary works where camaraderie remains a fundamental theme.