What Really Happened During The 2001 Anthrax Attacks?

Also known as Amerithrax, from its FBI case name, the 2001 anthrax attacks started occurring less than a month after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, and although the two weren't connected, both the American government and the American public were suddenly on as high alert as they'd ever been. Millions were afraid of opening their mail and any and all white powder was suddenly deemed suspicious.

Although the FBI claims that the sole perpetrator of the 2001 anthrax attacks was identified, more and more information has come out over the years that shows that the government's case wasn't as air-tight as they wanted everyone to believe. In the end, some accused the FBI of "dragging their feet" during the investigation, which took seven years to conclude. And when the FBI finally finished their investigation, it was difficult for many to accept their conclusions, especially since they targeted an innocent person along the way.

But what really happened during the 2001 anthrax attacks? And who did the government finally pinpoint as the culprit? This is the story of what really happened during the 2001 anthrax attacks.

What is anthrax?

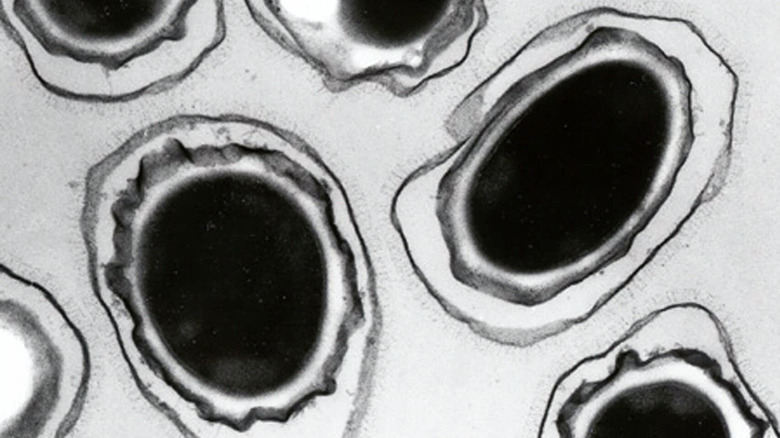

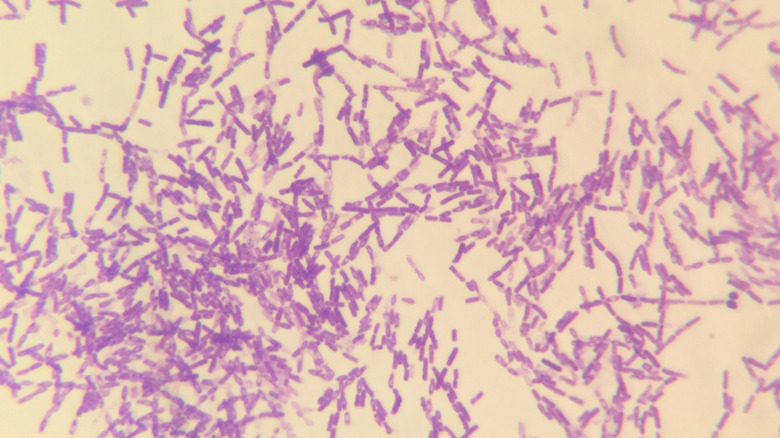

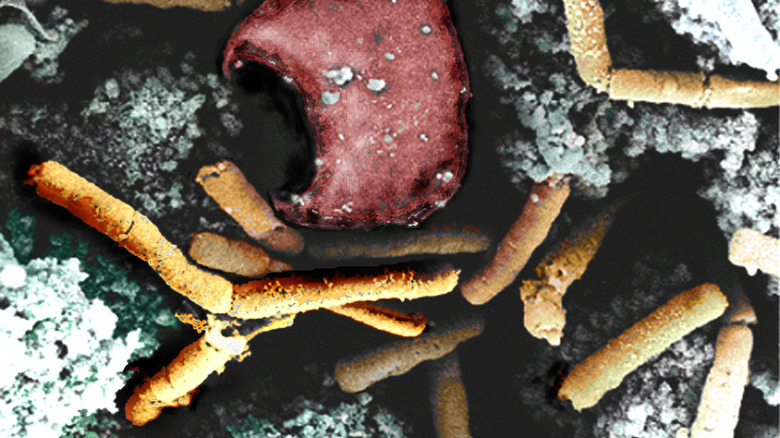

Caused by the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis, anthrax is a rare but life-threatening illness that is caused when B. anthracis enters the body. A person usually becomes infected with anthrax when bacteria enters the body through an open wound, but infections also occur through inhaling spores or eating contaminated meat, according to the Mayo Clinic. The American Medical Association writes that anthrax has been described by writers and scientists for thousands of years, and the "fifth Egyptian plague (circa 1500)" is thought to have been due to anthrax.

Depending on how anthrax is contracted, different types of anthrax can occur, including cutaneous anthrax, pulmonary anthrax, and gastrointestinal anthrax, and all of them have the potential to be life-threatening if left untreated. The CDC writes that when it comes to pulmonary (or inhalational) anthrax, symptoms can range from body aches, chills, and fever to stomach pains, vomiting, and shortness of breath. Cutaneous anthrax, on the other hand, presents as a group of small itchy blisters or bumps that turns into a painless ulcer with a black center.

Treatment typically involves multiple courses of antibiotics, but severe cases can also require continuous fluid draining and breathing assistance with a ventilator. Antitoxins have also been used to effectively treat anthrax, but it must be combined with other treatment methods.

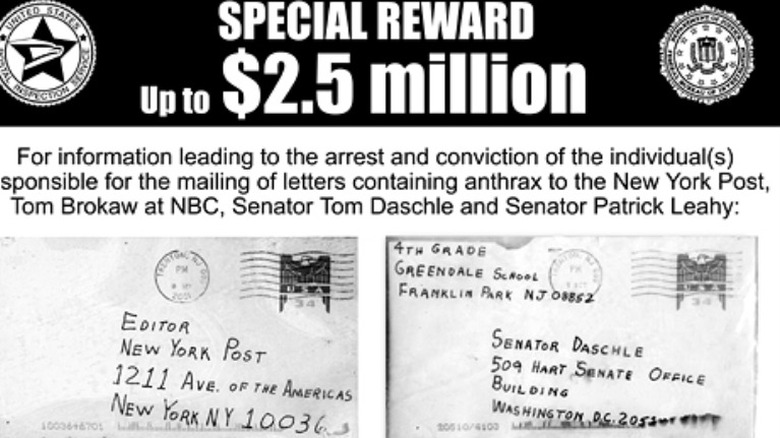

The first wave of letters

On September 18, 2001, five letters containing B. anthracis spores were sent out from a mailbox in Trenton, New Jersey. It took several days for them to arrive at their intended recipients at The New York Post, The National Enquirer, ABC, CBS, and NBC and according to Smithsonian Magazine, the letters were basically ignored as just a strange delivery. Casey Chamberlain, Tom Brokaw's assistant at NBC, was one of the people who came in contact with one of the letters. "There was one letter that looked as if it were written by a child. Something seemed unusual. I'd never seen a letter containing a granular substance. I mentioned the strange letter to my friends," per NBC.

On October 4, Robert Stevens, who worked as a photo editor with The National Enquirer, was hospitalized and diagnosed with inhalation anthrax. At this point, Stevens' anthrax diagnosis wasn't connected to the letters. If anything, government officials were initially reluctant to claim that the anthrax poisoning was intentional. Debbie Crane, a spokesperson for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services even tried to minimize the situation by stating that "anthrax happens."

Meanwhile, Chamberlain was suffering from severely swollen glands, but her doctor said it was just a reaction to her acne medication. Another one of Brokaw's assistants also fell ill around this time. On October 5th, Steven passed away, becoming the first anthrax death in the United States since 1976, NPR reports.

The second wave of letters

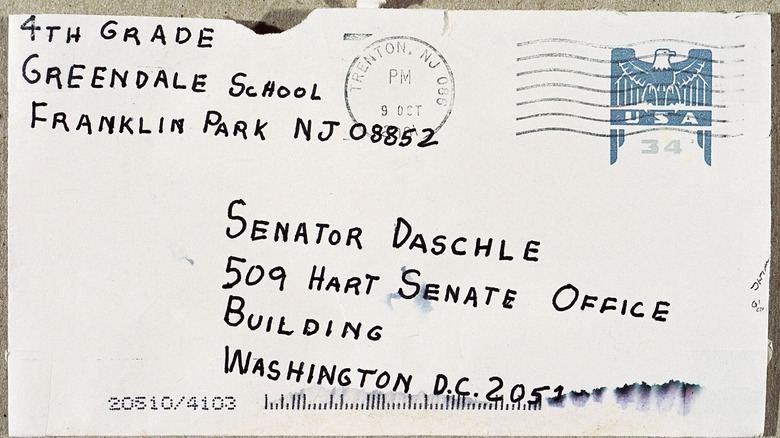

Around October 9th, two more letters with anthrax spores inside were mailed out from Trenton, New Jersey. This time, the letters were addressed to Tom Daschle, Democratic Senator from South Dakota, and Patrick Leahy, Democratic Senator from Vermont. At the time, Daschle was the Senate majority leader and Leahy was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

According to the Review of the Scientific Approaches Used During the FBI's Investigation of the 2001 Anthrax Letters, one of the letters, the one addressed to Senator Daschle, was opened on October 15th by one of Daschle's interns, Grant Leslie. Upon discovering the contaminated letter, the House and Senate buildings were closed for decontamination. The letter, addressed to Senator Leahy, wouldn't be found until November 16th due to a misread zip code causing the letter to be misdirected to the State Department mail annex.

The Smithsonian National Postal Museum writes that both letters bore a fictional return address and passed through the Hamilton Township facility and the Brentwood facility. And the day after the anthrax letter to Senator Daschle was discovered, a postal worker at the Hamilton Township facility tested positive for cutaneous anthrax. Another worker fell ill on October 17th and although the Hamilton facility closed on October 18th to be tested for anthrax, the Brentwood facility continued to operate despite the fact that postal workers like Thomas Morris Jr. and Joseph Curseen were starting to fall ill.

What did the letters say?

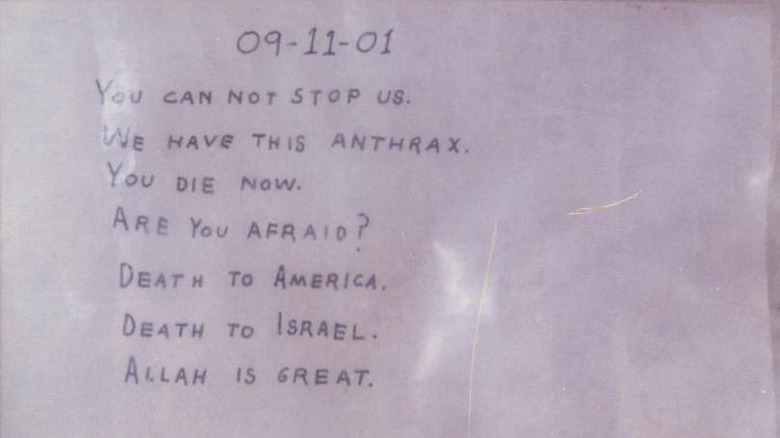

The letters included with the anthrax in the two batches of mailing bore similar messages but they weren't identical. According to the Amerithrax Investigative Summary, the letters in the first batch, which were recovered from Tom Brokaw at NBC and the editor of the New York Post, read: "09-11-01/ THIS IS NEXT/ TAKE PENACILIN (sic) NOW/ DEATH TO AMERICA/ DEATH TO ISRAEL/ ALLAH IS GREAT." Meanwhile, the letters to the senators read "09-11-01/ YOU CAN NOT STOP US./ WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX./ YOU DIE NOW./ ARE YOU AFRAID?/ DEATH TO AMERICA./ DEATH TO ISRAEL./ ALLAH IS GREAT." And unlike the letters to the senators, the first batch of letters didn't seem to have a return address of any kind.

All of the envelopes contained a photocopied letter and as of 2021, the originals of the letters haven't been recovered. Investigators also noted that all of the recovered letters had been cut down to an "irregular size by trimming one to three edges of the page."

What happened to those exposed?

Overall, at least 22 people became infected with anthrax due to exposure from the mailings. Half of the individuals contracted pulmonary anthrax after inhaling the B. anthracis spores and the other half contracted cutaneous anthrax through skin contact after spores got in through the skin. Out of the 22 people infected, 12 were postal workers, per the CDC.

According to the Amerithrax Investigative Summary, another 31 people tested positive for "exposure to anthrax spores" and an additional 10,000 people were considered to be at risk of exposure and were given antibiotics as a prophylaxis.

A total of 35 mailrooms and postal facilities were contaminated and out of the 26 buildings tested on Capitol Hill, B. anthracis was detected in seven buildings. Smithsonian Magazine writes that once it was confirmed that the anthrax infections weren't isolated cases, large quantities of mail were quarantined in an effort to prevent further infections. After having been assured by the CDC that envelopes contaminated with anthrax "would not be a danger to postal workers," postal workers as well as workers for both businesses and government agencies were supplied with gloves with which to open mail.

How many people died?

Out of the 22 people infected with anthrax, five people lost their lives. Robert Stevens of American Media was the first to lose his life on October 5 and Thomas Morris Jr. and Joseph Curseen, the two postal workers who became infected with pulmonary anthrax, both passed away on October 21th and October 22nd, respectively.

The fourth person to die as a result of pulmonary anthrax was Kathy Nguyen. According to The Washington Post, Nguyen, a 61-year-old Vietnamese émigré, was a hospital worker at the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital and was the first person to contract anthrax without having any ties to the media or the mail. In "American Anthrax," Jeanne Guillemin writes that Nguyen went to the Lenox Hill Hospital's emergency room on October 28th "too weak to describe her chest pains." On October 30th, blood tests confirmed anthrax infection, but by that point there was nothing that the doctors could do. On October 31st, Nguyen passed away.

The fifth death attributed to anthrax infection was 94-year-old Ottilie Lundgren, an equally curious outlier. According to Yale School of Medicine, Lundgren arrived at Griffin Hospital in Connecticut on November 16th and by November 19th, it was confirmed that Lundgren was suffering from pulmonary anthrax. Two days later, she passed away. Although no anthrax spores were found at her house, spores were found on a mail-sorting machine in a distribution center in Wallingford, Connecticut, "including the bin that contained mail for Lundgren's route."

Hoax letters

While investigators were trying to find out who was responsible for the anthrax letters, they were inundated with thousands of hoax letters. According to "Anthrax Attacks Around the World" by Tahara Hasa, by January 23, 2002, over 15,000 anthrax hoaxes were reported in the United States.

With the large number of hoaxes and false alarms being reported after the anthrax attacks, the CDC and local laboratories "were so overloaded with testing requests that they contemplated setting up triage procedures to prioritize tests," per Anthrax In America.

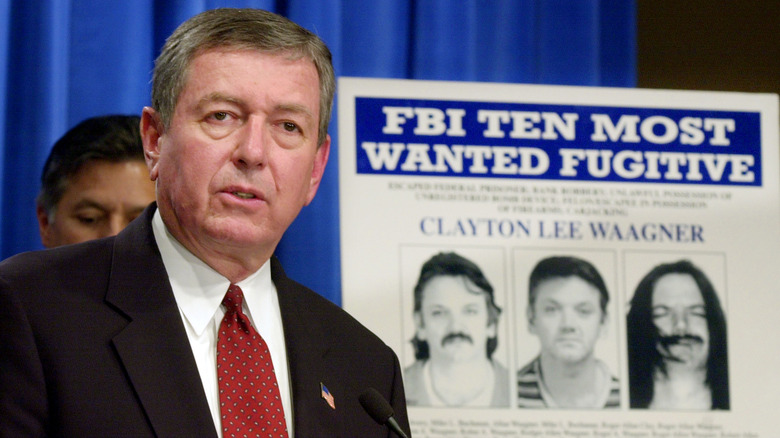

One of the many perpetrators of these anthrax hoax letters was Clayton Lee Waagner. Waagner already had a history of harassing and threatening women's reproductive health care clinics and after hearing about the anthrax letters in the fall of 2001, he decided to try a similar method. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, hundreds of letters were sent by Waagner to reproductive health clinics with the phrase "TIME SENSITIVE SECURITY INFORMATION, OPEN IMMEDIATELY" on the outside. The envelopes contained a white powder claiming to be anthrax along with death threat letters. "While Waagner targeted abortion clinics, he also mistakenly sent these 'anthrax letters' to several pro-life organizations." And according to TFAH, women's health facilities often received hoax letters of a potential bio-threat even before the anthrax letters attack.

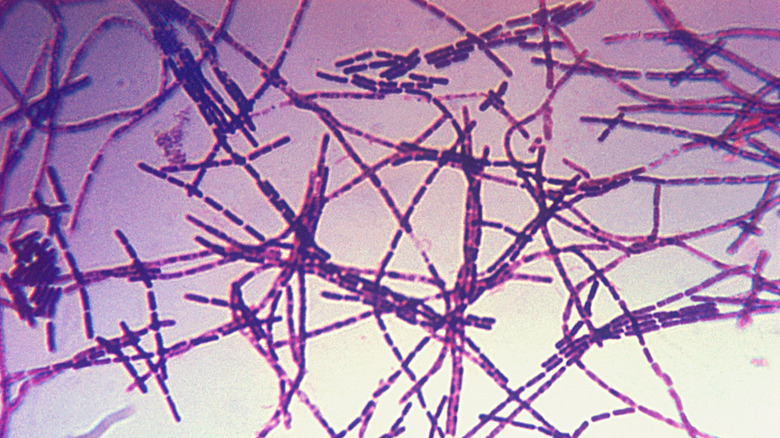

The Ames strain

When it was discovered that Stevens was suffering from anthrax in Florida, scientists rushed to try to figure out what strain of anthrax was responsible. According to Anthrax In America, doctors were initially hesitant to identify it as the Ames strain, with Dr. Martin Hugh-Jones even claiming "It's not the Ames strain, far from it." But on October 13th, microbiologists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory discovered that the anthrax strain implicated in the attacks was in fact the Ames strain, a strain of anthrax that was acquired by the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in 1981, per The Washington Post.

Dr. Paul Keim, one of the microbiologists who identified that the anthrax was the Ames strain, described the discovery as "chilling" not only because of its association with the U.S. Army, but due to what the army used the strain for as well. "We knew that it was highly virulent. In fact, that's why the Army used it, because it represented a more potent challenge to vaccines that were being developed by the U.S. Army. It wasn't just some random type of anthrax that you find in nature; it was a laboratory strain."

Destruction of the anthrax archive

After the Ames strain was identified, it was mistakenly linked to the Iowa State University laboratories in Ames, Iowa. In fact, the strain originally came from Texas and was only named the Ames strain because it was mailed to the U.S. Army with an Ames return address, Patch reports. But this fact wouldn't be realized until January 2002, almost three months after seven decades worth of old anthrax cultures were destroyed.

Rumors spread that the strain was stolen from the laboratory in Ames and upon hearing this, the Iowa Governor sent state troopers to guard the university and federal laboratories. Researchers tried to send the anthrax, more than 100 old anthrax cultures dating back to 1928, to the FBI, the CDC, and the USDA, but "none of the agencies were interested."

Out of fear of additional thefts, Iowa State University destroyed their anthrax archive on October 10 and 11, 2001. Iowa State Daily writes that it was going to cost $30,000 a month to guard the old anthrax cultures for 24 hours a day and in the end, it was decided that there was no use in keeping the old cultures. Norman Cheville, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine office, stated "Of course, we thoroughly and very clearly thought out what we wanted to do. If there had been any thought that these would have been useful to someone, we wouldn't have destroyed them, but there weren't."

Looking for the culprit

Because the anthrax attacks occurred one week after the September 11th attacks, the Bush administration reportedly pressured the FBI to find a link between Al Qaeda and the anthrax attacks. According to the former FBI director Robert Mueller, "They really wanted to blame somebody in the Middle East."

But The Atlantic reports that Dr. Steven J. Hatfill, a scientist who once worked for the USAMRIID, was the focus for most of the investigation. Although Hatfill had an alibi, there was a lot of circumstantial evidence that led some to zero-in on him as a target, taking their suspicions all the way to Capitol Hill when the FBI wasn't initially interested. By August 2002, the FBI and the Justice Department tailed Hatfill everywhere he went. And whatever they learned, they leaked to the press. The FBI also proceeded to run over Hatfill's foot in May 2003. Meanwhile, Hatfill was ticketed for "walking to create a hazard" and fined over the incident.

Hatfill kept insisting that he'd never had access to anthrax and was "a virus guy" but the FBI continued to consider him a suspect until early 2007, at which point they started focusing on microbiologist Bruce Edward Ivins instead. In 2008, the Justice Department settled a lawsuit filed by Hatfill, agreeing to pay him $4.6 million after his lawsuit accused the FBI and the Justice Department of leaking information to the media "in violation of the Privacy Act," reports The New York Times.

Was it Bruce E. Ivins?

Bruce E. Ivins was a microbiologist who worked at the U.S. Army's biodefense laboratory in Fort Detrick, Maryland. According to PBS, Ivins was initially involved in the anthrax attacks investigation and even mentioned the Ames strain by name in one of his emails and offered to include them in "ongoing genetic studies." Later, Ivins would be accused of submitting false samples and covering up an anthrax spill, which would add to the circumstantial evidence surrounding his guilt. But as ProPublica notes, the FBI has never been able to prove that Ivins created the dry powder from the wet anthrax at Fort Detrick, that Ivins wrote the notes mimicking Islamic terrorists, or that Ivins posted the two batches of letters. "It could prove only that he had an opportunity to do so undetected."

In the summer of 2008, the FBI searched Ivins' home and found a cache of ammunition and guns. Meanwhile, Ivins was struggling with his mental health and was briefly committed to a mental health institution in July 2008 due to threats he reportedly made after learning that he was to be indicted for capital murder. After being released, Ivins died by suicide on July 26th at the age of 62.

On August 6, 2008, the FBI announced that they'd finished their investigation of the anthrax attacks and had concluded that Ivins was the sole perpetrator. But as the University of Minnesota notes, this conclusion was "greeted with skepticism by many in the scientific community."