The Life-Saving Heroics Of Cholera Detective John Snow

In the early 19th century, Britain faced a cholera epidemic that took thousands of lives. The first few cholera cases were diagnosed in 1831, and by the following year, the disease had spread in London. Back then, medical professionals theorized that cholera was an airborne illness that spread from rotten organic materials. Authorities and doctors weren't prepared to face the epidemic, and there were disagreements among them on which measures to take to stop cholera from spreading, according to the National Library of Medicine.

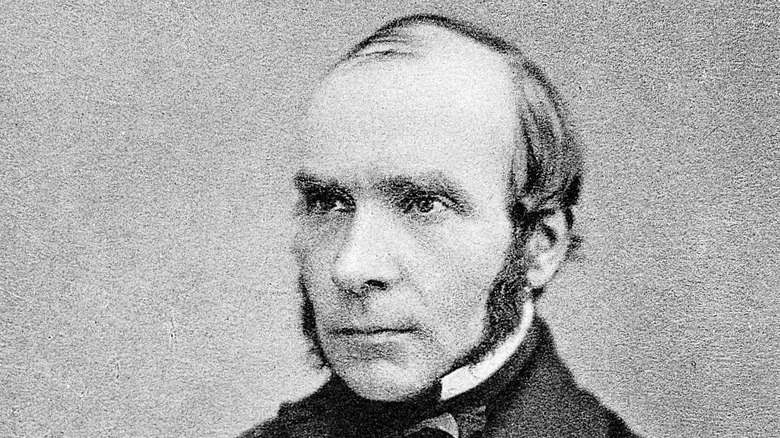

Cholera is a diarrheal infection contracted by ingesting bacteria-contaminated water or food, and when left untreated, it can kill a person within hours (via World Health Organization). Because this information wasn't known during the cholera epidemic in Britain, up to 7,000 people died of the infection within a 10-year period. At that time, physician John Snow didn't believe the popular theory that cholera spread through the air and person-to-person contact, so he did his own investigations to come up with the root cause of the illness, which he believed to be contaminated water.

John Snow maps the origin of cholera

John Snow was still an apprentice during the cholera outbreak in 1831. He went to medical school to further his studies and graduated with a medical degree from the University of London in 1844, per the Royal College of Surgeons of England. In 1854, there was a cholera outbreak in Soho, London, the third in the district since 1832. During the third outbreak, more than 550 people died in Broad Street alone within a span of two weeks, and based on that information, Snow wanted to test his theory that cholera was being spread through dirty water.

Using a map, John Snow plotted all the confirmed cholera cases. Upon further investigation, he found out that there was a water pump in Broad Street that residents used to draw water. He found that many of the people who died of cholera drank water from the pump.

According to Immunology.org, Snow then presented his findings in a letter to Medical Times and Gazette and said, "There has been no particular outbreak or prevalence in cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking water of the above-mentioned pump well." His theory wasn't immediately accepted, but the pump's handle was removed to test his assumption. Soon after, the epidemic was under control and it was discovered that the water from the well was, indeed, the source of cholera.

The contamination of the well

At that time, some districts in London were not yet equipped with a sewer system, and such was the case in Broad Street. For that reason, it was common for homes to have cesspits underneath or nearby. Further investigation into the cholera outbreak in Broad Street revealed that an infant, who died of diarrhea, was the first cholera case in that area (via Boston University Medical Campus). The infant's mother was interviewed and she revealed that she tossed a pail of her baby's diarrhea into the cesspit near her home, which was adjacent to the water pump. The area was excavated and it was discovered that the cesspool had a leak. With the wall of the well that led to the water pump decaying, content from the cesspool seeped into the well and contaminated the water.

John Snow's drive to investigate the root cause of the cholera epidemic helped save numerous lives, as well as lead to a better understanding of cholera. Today, Snow's efforts are memorialized with a water pump on Broad Street (now known as Broadwick Street), per National Center for Biotechnology Information.