The U.S. Embargo Of Cuba Finally Explained

To be honest, politics feels like some kind of minefield, and that's on the very best of days. There's just a lot that's always going on, and a ton of different topics that come and go, depending on who you're listening to and what issue has come into the limelight on any given day. So it's understandable if it gets hard to keep track of things.

And it just seems all the more confusing when one of the policies on the table actually originated in the early 1960s — the embargo of Cuba. Yearly, the embargo loses Cuba $685 million and the United States $5 billion (via History) and has cost Cuba about $130 billion as of 2018 (via Reuters), though the specifics over that period of time haven't always been straightforward. Or consistent, for that matter. Being as old as it is, the embargo on Cuba has seen its fair share of changes and revisions over the years, depending on the state of the world at the time (and especially the state of American politics).

So what's really the deal with the embargo of Cuba? Well, here's a bit of a primer on just what's been happening with this long standing piece of American foreign policy.

Why did the U.S. embargo of Cuba start?

Alright, let's get a little bit of the history out of the way here, because, unsurprisingly, the origins of the embargo are pretty firmly rooted in the complicated political history between the U.S. and Cuba. So, technically, you could just blame the Cold War, but here are the details.

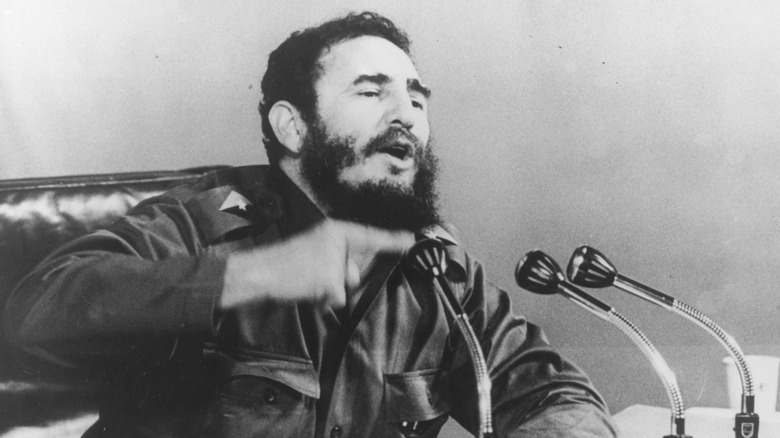

Things really started around the late 1950s, when, according to History, Fidel Castro himself claimed that he was interested in pursuing good relations with the U.S., despite having just overthrown the U.S.-backed government in 1959. The U.S. wasn't exactly so trusting, though; deposing a government would tend to do that.

The situation really began to sour from there. In 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stopped American exports of oil to Cuba, leading Castro to nationalize foreign assets, including U.S. oil refineries in Cuba. Per the Council on Foreign Relations, Castro also raised taxes on U.S. imports and started to look to the Soviet Union for a new trade partner. Not to be outdone, Eisenhower cut all diplomatic ties with Cuba and froze Cuban assets in the U.S.; by lowering imports quotas on Cuban sugar, the embargo was up in all but name.

Massive diplomatic incidents in the early 1960s (namely the Bay of Pigs Invasion) really drove the nail in the coffin on foreign relations, leading President John F. Kennedy to officially announce the full embargo on Cuba in February 1962.

Trade still exists, despite the embargo

The U.S. embargo of Cuba is a pretty complicated thing. It would seem like there being an embargo would imply that there isn't any sort of trade, right?

That's not what's happening here, though, and let's get that out of the way. The U.S. and Cuba still trade with each other, and quite a bit, mostly in the form of food and medicine. On top of that, Reuters adds that this isn't some sort of small-scale operation, what with the U.S. being one of Cuba's top five trade partners for the first time in 2007 (almost half a century since the embargo was first put into place). That statistic came just five years after the U.S. finally started exporting food to Cuba, due to a reform to the rules of the embargo that was proposed in 2000 (the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act, in case you're curious). It also coincided with the peak of U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba, which came in 2008 and amounted to $684 million, per a report by the Congressional Research Service.

More recently, the numbers have dropped, with 2020 export numbers more closely matching those in 2002. That said, trade hasn't completely disappeared. Sure, the legalities are tedious, but Cuba imported $123 million in chicken from the U.S. during the first six months of 2021, alone (via NBC News). And around 2016, it diversified its U.S. imports to include beer, baked goods, and chocolate.

The 1992 Cuban Democracy Act

If you want a pretty good overview of just what the embargo includes, then the Cuban Democracy Act is a nice place to start. In general, this act, the text of which is provided by Congress, tightened the embargo in that it made communication and trade really tedious.

Communication was allowed between the U.S. and Cuba, but the United States Postal Service had to provide a direct mail service between the two countries. Physical travel was also limited, with the act specifically talking about any "U.S. persons" visiting the country in order to finance any Cubans trying to leave for America. These limitations were born out of a fear that any sort of travel would be an opportunity for the Cuban government to get its hands on U.S. currency, which American politicians didn't want to allow.

Trade was even more of a hassle, though. Enter the "180-day rule": according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, any vessel which entered Cuban waters — whether to trade, or even just to get some repairs — would have to wait 180 days before it could dock in any U.S. port and unload freight. All of that waiting makes trade really expensive and pretty unattractive (via NBC News). And, on top of that, just about any vessel carrying goods or passengers to and from Cuba couldn't enter a U.S. port at all, barring specific authorization.

The 1996 Helms-Burton Act

The history of relations between Cuba and the U.S. really does hit a fair few low points, and 1996 was another of those years where that relationship soured even further. According to NBC Miami, the whole debacle got started on February 24, 1996, when some Cuban military jets shot down a couple of U.S. civilian planes. The attack killed members from the Cuban-exile group Brothers to the Rescue and subsequently provoked the U.S. government into creating the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act — or the Helms-Burton Act (via NBC News).

The Helms-Burton Act was a pretty general tightening of restrictions and a restatement of the policies the U.S. was trying to enforce, as well as a reminder as to why the embargo was up at all. The act, provided by Congress, starts with berating the Cuban government for human rights violations, then adds that the building of any nuclear facilities in Cuba or the "political manipulation" of Cubans to flee en masse to the U.S. would be detrimental in one way or another. The actual policies made it basically impossible for any U.S. institution to extend loans related to confiscated property in Cuba (in other words, U.S. business interests pretty much weren't allowed in Cuba), denied visas to Cuban citizens — mostly those involved in some way with the government — and effectively stopped some activities of human rights organizations, like gathering news or hosting certain educational activities.

Title III of the Helms-Burton Act eventually took effect

Even though the Helms-Burton Act went into effect in 1996, it wasn't fully in effect until 2019. See, Title III of this particular act has always been sort of controversial (via Skadden); that's probably why it's been suspended this entire time.

So, what's Title III? Per NBC News, it allows Cuban-Americans the opportunity to sue anyone — individuals or companies — for the use of property that was confiscated from them by the Castro government. Initially, this piece of legislation was written due to the Castro regime confiscating property from citizens without compensation; trafficking in that property could bring in profits to the government and cripple the embargo.

Anyone with business ties in Cuba could be subject to lawsuits, including foreign business owners whose home countries aren't involved in any embargo. Foreign businesses could be punished for their investments in Cuba or have their assets seized — not exactly desirable. Cuban-Americans were more pleased, though. They got the chance to regain property that was wrongfully seized from them, and it proved that the U.S. was willing to fight for their rights.

All that said, the policy is tricky. The property needed to have been worth $50,000 at the time it was seized, and the entity being sued needs to own assets in the U.S. Plus, lawsuits are expensive and would require original documents from Cuba to prove ownership. Maybe it's not surprising that only a couple thousand cases have been filed.

Other countries were told not to trade with Cuba

Even though this is the U.S. embargo of Cuba, it was never really meant to only affect those two countries alone.

Per Congress, the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 urged the president to push other countries to take part in the embargo, whether or not they were already trading with Cuba. After all, the more countries that get involved in the embargo, the more hypothetical pressure that would put on Cuba.

But this wasn't just a friendly favor being asked of foreign countries; the act itself also added that failure to comply could lead to further sanctions. In effect, if another country decided that they still wanted to trade with Cuba, then the U.S. could decide to impose sanctions on said other country for, in a sense, assisting Cuba. And like Cuba, they might become ineligible to receive aid from the U.S. under the Foreign Assistance Act and could have a harder time getting their debts forgiven or reduced.

The Helms-Burton Act (via Congress) strengthened this particular idea even further, adding certain actions to the definition of "assistance" (namely certain financial transactions). And instead of potentially punishing countries for assisting Cuba, that punishment became a certainty. To top it off, the act also recommended that the United Nations Security Council institute an international embargo against Cuba, officially involving the entire world in what started as a purely American policy.

The embargo has changed a lot over time

A bunch of different acts and policies have shaped the exact nature of the embargo on Cuba over the years, depending on contemporary political climates (and who was leading the U.S. at the time, to be honest).

For one, the embargo has actually been semi-lifted in the past. Early in the embargo, travel restrictions were actually such that Americans could travel to Cuba but weren't allowed to do so with their U.S. passport (via The Washington Post). Under President Jimmy Carter, though, those restrictions were lifted, allowing for travel and moving toward more normalized relations, which coincided with both countries reopening interests sections within other embassies, making for reopened communication. Similar policy changes came with the Obama Administration, which, overall, eased travel restrictions. Per The New York Times, tourism still wasn't allowed, but Americans could freely travel without special permission, so long as it was done for educational purposes (like visiting museums and learning about Cuban culture). That also came with Cuba being removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism in 2015 and the reopening of embassies (via Council on Foreign Relations).

A lot of that got rolled back under the Trump Administration, though. Cuba was reinstated as a state sponsor of terrorism, and the embargo was tightened again, restricting trade and financial transactions (via PBS) and making it near-impossible for Americans to travel to Cuba, per AP.

Other nations don't really agree with the embargo of Cuba

There's plenty of debate to go around about the U.S. embargo of Cuba, especially when you're looking within the U.S. itself. But if you turn your eye to the world stage and what the rest of the world actually thinks of the embargo, you get a pretty different story.

Foreign countries really aren't a fan of the embargo, to put it plainly. That was especially true after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union. After all, Cuba had been relying pretty heavily on its relationship with the Soviets to effectively stay afloat, so why keep up the embargo anymore? It seemed pointless and appeared to cause more suffering to the Cuban people than to the Castro regime itself (via The Heritage Foundation).

More than that, though, the embargo hurts the economies of a bunch of countries — not just Cuba and the U.S. Any products shipped to Cuba that contain at least 10% American-made content — regardless of what country is shipping those goods — become subject to the embargo, per NBC News, which means they suddenly require official licenses (and a whole lot more tedious paperwork). Plus, as of 2019, any individual or company that's said to have "trafficked" in properties seized by the Castro regime are at risk of being sued. That can potentially include foreign entities, which isn't super appealing to other countries with financial stakes in Cuba (via Skadden).

Ending the U.S. embargo of Cuba requires some change

The embargo has been going on for decades now, and it's something that, as of 2021, has still been a relevant topic in the world of politics. All the same, it's not like the embargo was planned without an end point in mind. (That just sounds sort of ridiculous).

So, what is that ending, exactly? Well, there are a couple of different steps, each with specific requirements — all of which are centered on Cuba's political system (via Congress). One of the earlier parts of that overall plan has to do with the fact that Cuba wasn't a valid recipient of a couple of pieces of legislation that provided humanitarian aid (in the form of food and medicine) to foreign countries. Regaining access to that aid required Cuba to actively take steps to implementing free elections, work to respect human rights, and stop providing aid to potentially violent foreign groups.

Going a step further, there are the conditions for the sanctions to be dropped entirely, which are pretty close to the ones already mentioned: actively conducting free elections with multiple, opposing political parties, establishing a free market, ensuring civil liberties for its people, and instituting constitutional change to uphold all of that.

The president can report to Congress if that's the case — Congress being the ones to actually decide to lift the embargo — at which point they can send aid to Cuba and provide any sort of emergency relief.

Maybe the embargo should be lifted

With the embargo of Cuba being such a longstanding policy, there are plenty of people who argue that, at this point, there isn't really any reason to keep it up anymore.

Opponents of the embargo argue that the U.S. is missing out on massive opportunities by making trade with Cuba so difficult. The Congressional Research Service's report goes into all of it, explaining that Cuba quickly became a huge market for both agricultural imports and exports, just between 1956 and 1958. So historically, there's some basis for the speculation that follows.

Essentially, the U.S. could potentially become one of Cuba's largest trading partners, because the logistics seem really favorable, were the embargo to be lifted. Geographically, the U.S. is super close, making shipping relatively quick and cheap, and it can already provide many of the products that Cuba tends to import anyway. On top of that, Cuba imports 80% of its food — a space that U.S. providers feel they could fill. And, if travel restrictions were no longer an issue, then exports of foods like pork and beef to Cuban tourist locations could also provide further profits. The American agricultural sector doesn't want to lose out on the potential market in Cuba, seeing the restrictions placed by the embargo as their main obstacle.

Plus, there's the argument that the embargo has hurt the Cuban people, not the government, and done nothing to advance their freedoms, which seems pretty self-explanatory.

Maybe the embargo should stay in place

Given that the embargo has lasted as long as it has, it only makes sense that there's some sort of argument as to why. And that argument mostly circles around The Heritage Foundation's assertion that the embargo will work one day. It'll apply enough pressure to force the hand of the Cuban government into agreeing to the conditions set out by the U.S.

ProCon.org gets into some more detailed arguments, though. For one, Cuba has been included on the U.S's list of state sponsors of terrorism in the past (and, as of 2021, is now back on that list, per the U.S. Department of State). So maybe, in that case, sanctions are kind of warranted. On top of that, there are the morals that get drawn into the question, and the argument that holding up the embargo equates to standing up to a cruel and dictatorial regime. The U.S. shouldn't give up its moral values, sort of in the same way that lowering the embargo could potentially look like the U.S. was weak in its convictions. After all, Cuba still hasn't actually agreed to any of the terms set out; it hasn't made any changes to its political system, so there really aren't grounds to lift the embargo at all. And if the embargo was lifted at this point, all those profits from trade might just go to funding the Cuban government, not helping the people.