The Worst Massacre Of Native Americans In US History Explained

The history of relations between the United States government and Native American tribes has never been particularly favorable. There's probably a pretty good chance you've heard of some of the pretty awful things that have happened — after all, there's more than a few of them, taking place over the centuries.

But there's also probably a pretty good chance that you've never actually heard of the deadliest massacre of Native Americans in all of U.S. history. And that's just kind of crazy, right? How could most people have never heard of it? You'd think that this bit of information would've cropped up somewhere or another.

Except for the fact that it's not really talked about anywhere, and the passing of time has pretty thoroughly hidden it from us. In the winter of 1863, blood was spilled all over the lands near Preston, Idaho (which was, at the time, part of the Utah territory). The rage-filled slaughter left bodies scattered across the ground, left to be picked away by wildlife and buried, to the point that, in the decades since, farmers would uncover human remains by plowing their fields (via KUER).

The Bear River Massacre was seriously bloody, and without equal in American history. Here is the worst massacre of Native Americans in U.S. history explained.

Tensions between Native Americans and the expanding United States

Let's get some of the historical context out of the way right at the start. When it comes to relations between Native Americans and the United States government, things have never really turned out too well. And that's just a general statement.

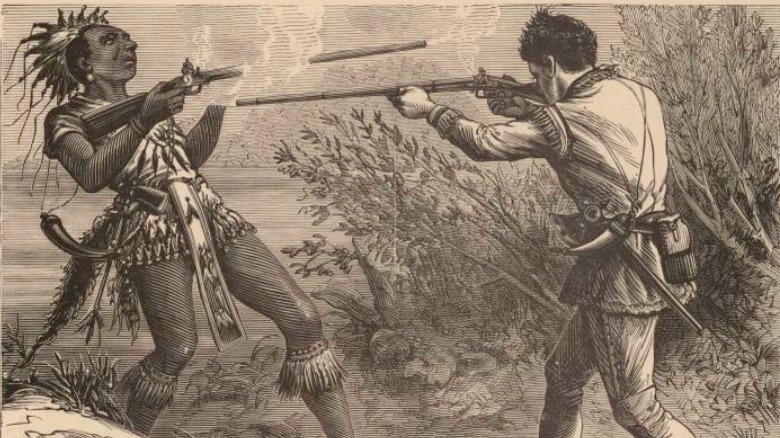

History explains that these problems have always been around, even before the U.S. itself was. Native American tribes allied with both British and French settlers, getting pulled into their wars and politics, despite it never really benefiting them (or actively harming them). Then, with the 19th century came the idea of expansion, of pushing the border of the U.S. further and further in order to grow the country — the idea that, overall, became known as Manifest Destiny. But those ambitions ended up bringing American settlers into even more contact with Native American tribes, who became roadblocks to the dream of Manifest Destiny, according to KUER.

Native American autonomy was slowly whittled away, as was their land, with the U.S. government refusing to recognize Indigenous tribes as independent nations worthy of diplomatic talks and treaties. Instead, they were subjected to policies like President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act, which kicked them off their land and forced them onto the infamous Trail of Tears. No small number of Native Americans tried to fight to retain or recover their lands and rights, only to be usually met with defeat and a long history of bloodshed.

Problems between the Northwestern Shoshone and Utah settlers

Even with all of the overall tensions between Native Americans and white settlers, if you took a look within Utah, there were some problems particular to that one specific region.

On one hand, there were those more general issues, like the large influx of Mormon settlers and miners. According to "Racial Conflict in Early Utah: Mormon, Native American, and Federal Relations," the native Shoshone were left starving and destitute, federal agents completely unable or unwilling to do anything, pushing them to steal horses from the settlers and killing their cattle for food.

A report from the Department of the Interior also mentioned that Chief Bear Hunter of the Northwestern Shoshone allegedly held a young white boy hostage, and a bloody confrontation between soldiers and some Shoshone in late 1862 led to supposed retribution by Native Americans in January 1863. There were accusations thrown at the Shoshone for a deadly attack on a group of miners.

Warrants went out for the Shoshone chiefs, though it's worth noting that, according to BYU, it wasn't even within the court's jurisdiction to issue those. Beyond that, Mae Parry — one of the elders of the tribe — said that those episodes of stealing were done by groups of "troublemakers," and the Northwestern Shoshone weren't themselves responsible (via Indian Country Today). But the settlers saw all Native Americans as the same and blamed them, regardless.

The U.S. Army was ready to punish the Shoshone

With news of the growing unrest in Utah spreading, the U.S. government decided to deal with what they'd termed the "Indian Problem." And the troops they dispatched to take care of the situation in Utah weren't exactly too upset about it.

Well, that's not entirely true. Per KUER, many of these soldiers had signed up to fight in the Civil War but ended up sort of stuck out in the Western territories with relatively little to do. The "Indian Problem" gave them something more tangible — some sort of action that they could be excited for.

Their leader, Col. Patrick Edward Connor, was just as eager. Much like his troops, Connor was assigned to a post out West, which meant that he, in particular, wouldn't be able to make any sort of name for himself (via Indian Country Today). He didn't think there was any glory in it. And on top of that, he just didn't like the Native American tribes, which really made him the perfect candidate for the situation when things appeared beyond saving (even though the Shoshone's Chief Sagwitch had every intention of finding a peaceful resolution).

So he was pleased to be given this command. Per BYU, he was glad that these were supposedly the same Native Americans who had killed people on a mail route 15 years earlier and had every intention to "chastise them," taking no prisoners in the process.

The Army marched on Bear River

On January 29, 1863, those building tensions finally came to a head. Col. Patrick Edward Connor had managed to gather a group of about 200 volunteer soldiers from California — aided by Brigham Young's Utah militia — and started marching them toward the winter village of the Shoshone (via Legends of America). He was determined to get this done in the winter, his logic being that Shoshone warriors wouldn't be as effective when there were women and children at the scene, per the Department of the Interior. The journey also gave them time to spread plenty of misinformation about what was going on.

That morning, the soldiers arrived at Bear River with dramatic flair. The Shoshone could see what looked like a giant, moving cloud descending the bluff (via Smithsonian Magazine). But it wasn't a natural occurrence; it was the breaths of men and horses fogging up the air and heralding their arrival. The Shoshone bunkered down to defend their home, even managing to fend off the initial assault and causing a few casualties (via BYU). But they weren't able to hold out forever, with Connor's use of the cavalry to flank them managing to break through their lines. Army soldiers flooded into the village and carved through it. Once the smoke cleared (literally), over 250 Native Americans had been killed — including one of the Shoshone chiefs — and 160 were captured. In contrast, the Californians suffered only 14 deaths and just over 50 wounded.

The atrocities of the Bear River Massacre

The Bear River Massacre is notable not just for the number of Native American casualties but also for how many of those casualties were inflicted. This was slaughter in the most violent sense of the term.

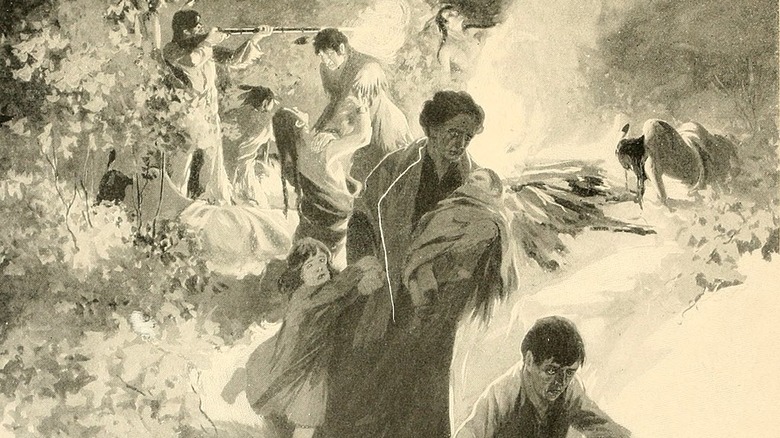

Once the soldiers broke their way into the village, no one was safe. Gunfire gave way to hand-to-hand combat, with men using their rifles as clubs. Some of the Shoshone tried to flee by jumping into the river, only to be shot in the process. Chief Bear Hunter was singled out by the soldiers and tortured upon being caught. Per Indian Country Today, he wasn't just whipped, kicked, and shot — he was killed by a heated bayonet rammed through his head. And if that wasn't horrific enough, well, his family had to watch it all happen from where they hid.

To make things even worse, all of those things happened after the Shoshone had immediately tried to surrender. According to Sgt. William Beach, they cried for quarter, only to be ignored, making the battle look "more like a frolic than a fight" (via BYU).

But the horrors didn't end with the battle. Some soldiers went around after and assaulted the women, while others would kill injured children by bashing their heads in with their weapons (via Legends of America) or by grabbing and swinging them by their ankles, smashing their heads against the rocks (via KUER). All done in the name of saving ammunition.

Surviving the Bear River Massacre

The stories of all the things that happened during the Bear River Massacre are absolutely horrifying. But for all that the stories of death are awful, the stories of survival are pretty scary.

The sons of Chief Sagwitch fall into this category, per Indian Country Today. One of the younger sons — Yeager — remembered running through the battlefield, somehow managing to dodge the bullets that flew through the air. What kept him alive was hiding among bodies, pretending to be dead. He waited there for hours, eventually opening his eyes, only to come face to face with the end of a rifle. The soldier holding the weapon aimed it at him three times but apparently couldn't bring himself to pull the trigger. Soquitch, one of Sagwitch's older sons, also managed to survive the battle, escaping on horseback, but not without his girlfriend getting shot in the process.

Others tried a bunch of other means of escape; mothers jumped into the freezing river to swim away, only for the babies they held to drown. Some hid in the river itself, waiting under ice or other bits of greenery to stay safe.

And even years later, Darren Parry, a councilmember of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, said his grandmother would tell him that survivors of the massacre could still hear the cries of dead children whistling on the winds through the willow trees (via KUER).

A massacre? Or a battle?

As explained by NPR, words like "massacre," "battle," and "riot" all carry different implications with them.

According to All That's Interesting, U.S. Army reports documented the events that occurred at Bear River, referring to it as the "Battle of Bear River," while the Shoshone called it the "Massacre of Boa Ogoi" (the Shoshone name for the river). "Battle" makes it feel like the bloodshed and blame fell on both sides equally, while "massacre" is decidedly more one-sided — and the reports from varying sources kind of fit with those two conflicting views.

When it comes to casualty counts, it's believed that the U.S. Army under-reported the numbers, citing 224 casualties (via BYU), while most modern estimates fall between 250 and 400, with one Danish traveler actually counting 493 bodies. A pretty notable difference. And the site itself was described differently, depending on who was doing the talking. American soldiers saw Shoshone warriors hiding in holes, which they described as fortifications and trenches dug out specifically for the battle (via the Department of the Interior). But that's probably not what they were. Per Indian Country Today, it's more likely they were either meant to make traversal of the steep riverbank easier or were foxholes dug by children.

The Mormon Church and the Northwestern Shoshone

Everything surrounding the Bear River Massacre took place in Utah around the mid-19th century, which also just happened to be around the same time that the Mormons began to settle there.

That said, their place in this story is a little confusing. A report from the Department of the Interior paints the relationship as contentious, with the Mormons potentially allowing — or even taking some relief in — a massacre. According to Legends of America, Brigham Young also contributed soldiers to Col. Patrick Edward Connor's forces, more directly taking part in the massacre itself.

Or things weren't that antagonistic. Smithsonian Magazine says that the two groups worked together, trading supplies and knowledge. According to "Racial Conflict in Early Utah: Mormon, Native American and Federal Relations," Young also instituted a policy of "feeding the Native Americans" as a way to keep the peace, rather than fighting them (though that came with a view of Native Americans as inherently lesser than the Mormon settlers).

Either way, though, in the aftermath of the massacre, the 150 survivors, led by Chief Sagwitch, reached out to the Mormons for help, which they did provide, building them a ranch and teaching them farming techniques (via Indian Country Today). Those survivors also became members of the Mormon church, which later would help their descendants buy back the land.

The site of the Bear River Massacre has been sort of lost

The place of the Bear River Massacre in history is a little strange. Despite being regarded as the deadliest massacre of Native Americans, it's been almost completely lost to time.

Strangely enough, the site of the massacre itself underwent something similar. Future generations of the Northwestern Shoshone can recognize where their ancestors used to live in the valley. As detailed in Smithsonian Magazine, Darren Parry, a descendant of Chief Sagwitch, can see what drew his ancestors to the location and how the landscape interacted with their way of life. But researchers don't feel like they have the same clarity.

Kenneth and Molly Cannon, archaeologists working at Utah State University, decided to try and find the exact site of the battle — not something that seemed too difficult and which should've resulted in uncovering artifacts from the battle itself: bullets, bodies, remains of homes, and the like. But that didn't really happen. Following historical descriptions led them to a seemingly perfect site that didn't turn up any relics. Well, aside from a single lead ball and a prehistoric hearth from circa 900 A.D., which is cool, but not what they were looking for.

Further research on the terrain, though, revealed that everything had probably shifted, with Bear River actually being 500 yards south of where it would've been in the mid-19th century. The same process probably also buried the site of the massacre under years of sediment.

History doesn't really remember the Bear River Massacre

The Bear River Massacre is known as the deadliest massacre of Native Americans in U.S. history. But, there's probably a decent chance that you'd never heard of this event. Why?

The Bear River Massacre took place in 1863, right in the middle of the Civil War. At the time, people weren't paying attention to the western territories; everyone's attention was glued to the east (for reference, the Battle of Gettysburg was only a few months away, so that kind of makes sense). The Civil War just overshadowed everything else, both at the time and since. The Bear River Massacre is often left off lists of the bloodiest and most important Native American massacres, despite having more casualties, per Legends of America.

Even local media at the time didn't cover the story. Eastern and midwestern newspapers didn't report on it, and only a small handful of newspapers based in Utah and California — you know, where this was relevant — barely published any accounts of it (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Or this could all come down to perspective and discrimination, according to Hubert H. Bancroft (via the Department of the Interior). A massacre of Native Americans was allowed to be lost, but if the roles had been reversed — if the Shoshone had killed a regiment of U.S. soldiers — then that'd be a different story.

Efforts to remember what happened at Bear River

With how dramatically the Bear River Massacre has been basically erased from history, there have been more recent efforts to try and remember all that happened there and all those who were lost.

Over time, monuments have gone up at the site to commemorate what happened, the earliest being erected in 1932. Although, per "Racial Conflict in Early Utah: Mormon, Native American and Federal Relations," this particular monument paints the Mormons as saviors, swooping in after a battle between savage natives and purely peaceful settlers. It's not exactly the version of the story accepted now. According to KUER, another monument was also put up in the 1950s, standing near the road. In the 1990s, the National Park Service stepped in and added a series of signs to the area, explaining the events of the massacre.

More recently, the Shoshone Nation did manage to buy back around 550 acres of land where the massacre took place, with the intention of building up an interpretive center where they can teach more people about their ancestors, as well as about their ancestors (via Smithsonian Magazine). An article from Utah State University also mentions that the Boa Ogoi Development and Interpretive Center would include restoring the land's natural habitat — planting willow trees, reintroducing native species, or at least mimicking the effect of those animals on the region.