Creation Myths From World Religions Explained

One of the best things that humans have ever invented is the ability to tell stories, and according to University of Connecticut professor emeritus in English David Lemming, stories capture the essence of what it means to be human. He says (via NPR): "...humans are defined by the fact that they tell stories, and particular myths reflect particular cultures, but they also reflect the human culture. So, if you put together all the myths of the world, you'll get a picture of the human mind, as it were."

And that's pretty cool. Humankind has been trying to learn for a long time just where they came from and where they're all going, and that's where religion comes in. Lemming says that tales of creation are called myths because they're "a story that's often considered sacred, but essentially it's a story in which the events that take place don't normally take place in our everyday lives."

The creation myths of the world's religions provide a valuable touchstone that helps countless people get through their lives on earth — lives that, let's be honest, can be awful and stressful and downright horrible sometimes. Religion gives us a chance to believe in something bigger than ourselves — or our problems — and the idea that something divine decided to make us along with the rest of the world is kind of neat. Let's look at some of the world's creation myths, and why they're so important to so many.

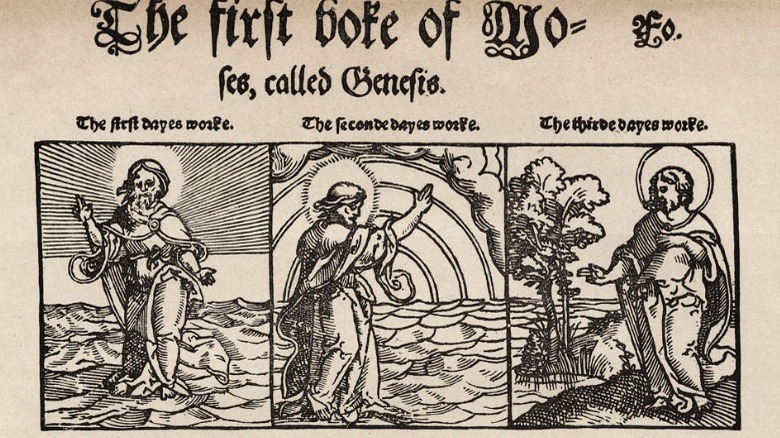

The six days of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism

There's a lot of things that separate the world's three biggest religions, but go back to the beginning of creation, and their stories are pretty similar.

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism all have six days of creation by a divine being at the beginning of the world, but that's not to say they're all identical stories. Understand Christianity and Chabad both describe those six days similarly: God created light on the first day, the sky on the second, formed the land and seas of the earth on the third, made all the celestial bodies on the fourth, added fish and birds on the fifth, and then did the animals and humans on the sixth.

So far, pretty straightforward — but the six-day creation story from Islam has some major differences. According to the BBC, the story is referenced in places across the Qur'an, but not told in one single go. One of the big differences is one that's easy to overlook: This story, too, says the world was created in six days, but while the Christian story interprets this as six 24-hour periods, Northern Arizona University says the word the Qur'an uses for "day" is "youm" — and it's a word that references a period of time that's anywhere from 1,000 to 50,000 years long. Those "days" are what we'd think of as eons, and they also note that it puts this version more in line with scientific findings about the age of the earth.

The first humans of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism

The big three world religions of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism also have something else fascinating in common: The creation story of Adam and Eve. Bible Gateway, the BBC, and Chabad all tell a similar story of a divine being — God, Allah, or G-d — that takes mud or dust and creates the first man. Then, he creates a companion for Adam, and things go sideways from there.

It's a story that shows that humankind has been screwing things up from the very beginning, but it's also been incredibly divisive. NPR found that around 40% of Americans believed in the Adam and Eve creation story in 2011, but there was a fascinating footnote to that: Among those who didn't believe were a group of conservative Christian scholars — like Dennis Venema, a Trinity Western University biologist — who were starting to doubt. He was pretty straightforward about it: "[Adam and Eve] would be against all the genomic evidence that we've assembled over the last 20 years, so not likely at all."

There's another big difference in the way Adam and Eve's story goes, too. While Bible.org says there are no passages that specifically say the pair were forgiven for eating the forbidden fruit, they were forgiven in the Qur'an.

Baal and the sea monsters

When it comes to the Bible, it's Genesis that usually gets pointed to as the OG creation story — but according to Haaretz, there's an even older one. It's mentioned in a few different books, including Job, Isaiah, and it's in Psalms, too. It's the story of Leviathan, and it basically says that God came down, defeated the massive sea monster, and "gavest him to be meat to the people inhabiting the wilderness." Along with that, God also made light, sun, night, day, the seasons, and the boundaries of the world.

Strangely, archaeologists have even discovered the source of the story — it's a retelling of a Canaanite creation story. Preserved on ancient tablets is the story of Baal, a storm god who killed a sea god called Yam, and in doing so, created the division between sky and ocean. The Canaanites aren't the only people to tell this story, either. In the Babylonian version, it's Marduk who slays the sea monster Tiamat, and it's also a theme in Greek, Norse, Slavic, and even Hindu stories. (Adam also has Babylonian counterparts: Adapa misses out on becoming immortal when the god of wisdom convinces him not to eat the food he's offered by other gods.)

There's no denying that the Bible was influenced by the Canaanite tale: The text of Isaiah 27:1 is nearly word-for-word taken from one of the ancient Canaanite tablets.

Is Buddhism's creation story a myth or a fable?

Buddhism's creation story is a little different from other religions, because according to the BBC, when the Buddha was asked how the earth started, he didn't answer. That's in line with the basic principles of Buddhism: Rather than focus on the unknowable, try to make the present a better place.

That said, there is something to a creation myth in the Agganna Sutta: Learn Religions says it's kind of a fable wrapped in a creation story. It's the story of two Brahmins (members of the highest rank of India's class system) who talk to the Buddha about their experiences becoming monks and living among the lower ranks. They say they're not being treated very well, but Buddha reminds them that at the end of the day, everyone's human.

He tells a story of the cosmos being born and reborn, and of "luminous beings" who exist in pure happiness. The earth was formed in the last rebirth, and when the beings went to earth, they gorged themselves on all it had to offer. First, the earth itself — then fungus, then rice, and so on. The beings fell victim to greed, lust, distrust, and finally, they created other evils of the world. To deal with those evils, they formed the caste system — but anyone of any caste can be good, just as anyone can be bad. In the end: "... he with wisdom and good conduct is the best of gods and men."

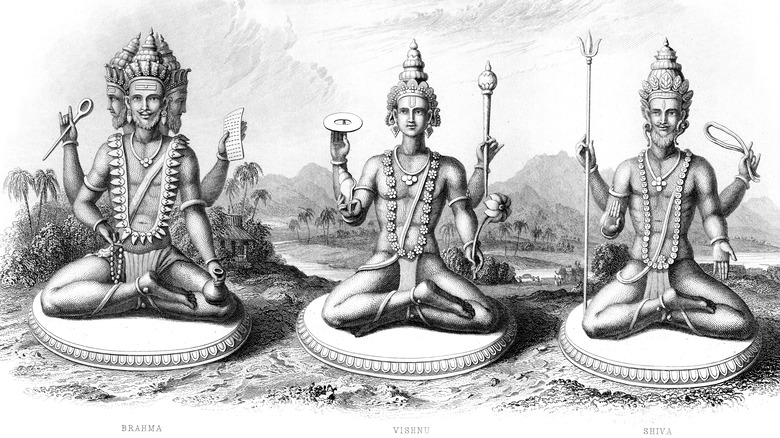

Hinduism's many creations

Hinduism, explains Patheos, says that the universe wasn't created just once, but exists in a pattern where it's created over and over again. That means there are numerous creation stories, but that's not saying they don't have anything in common, because they do. While other religions — like Christianity — separate the divine and our material, earthly world in what's called Western dualistic traditions, Hinduism features stories that are largely rooted in fundamental nondualism. In a nutshell, it means that humans are living in a divine or semi-divine world.

The creation cycle is overseen by three deities: Brahma creates, Vishnu sustains, and ultimately, Shiva destroys. How the creation and destruction happen vary by the telling, in a cycle called the Brahmaloka (says Learn Religions). The cycle governs not just Earth, but all worlds. The lifespan of our world is four billion years, and it's the same as a single day in the Brahmaloka: That cycle will repeat for 100 years, and at the end, Brahma will die and be reborn 100 years later — and everything will start again.

Hindu creation stories are beautifully epic, like the one that says the universe and everything in it was born when the Primeval One became bored and decided to separate Itself into the world and everything in it — all things for It to love and care for.

Pan Gu: Daoism's first man

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says that pretty much any attempt to define Daoism is going to be incomplete and controversial, so let's just say that it's formed the backbone of Chinese philosophy since at least the 4th century B.C. Daoism comes with a creation myth, and it's the story of Pan Gu. He was the first man, says Britannica, and there's a few different versions of how the world came to be.

First, says the Shen Yun Performing Arts, there was nothing but an egg. Inside the egg was everything that would be, and as time went by, the yin and yang made a baby called Pan Gu. After 18,000 years of growth, he first woke, then split the egg in half. As he emerged, one half rose into the sky and the other formed the earth... but it was small. Pan Gu continued to grow and continued to hold the pieces of the egg for another 18,000 years, and when the world had been formed, he died.

The parts of Pan Gu's massive body were transformed into the rest of the world: His eyes became the sun and the moon, his blood became the rivers, and his hair turned into the plants. His spirit became the first humans — which explains the belief that humans are considered to be the soul of the universe.

The female submission of Shintoism

Shinto, says Asia Society, translates to "way of the gods," and it's been at the heart of Japanese beliefs and culture since before the written word. Along with an acknowledgement of the divine spirit that exists in the oldest parts of the world, there's a creation story that teaches life lessons on the importance of observing tradition.

Michigan State University explains that it started when the particles of chaos separated formed the heavens and earth. That brought into being five deities — who retreated from the world and were followed by pairs of brother-and-sister kamiyo-nanayo.

Izanagi and Izanami were the youngest and the most important, as they were the ones that created the islands of Japan, then discovered first marriage, then sex. When they had their first child together, he was so misshapen that they abandoned him; they came to the conclusion that he had been born that way because while they embarked on their sexual rituals, Izanami had spoken first. Her affront to the natural order of things had caused her son to be deformed, and according to the BBC, the story is used to support some of the foundations of the old beliefs: Women are subservient, children who aren't perfect can be abandoned, and anyone who disrupts the natural order of things or doesn't respect traditions will have very bad luck, indeed.

The oft-spoken tales of Maori creation

According to historian and composer Te Ahukaramu Charles Royal (via The Encyclopedia of New Zealand), there is no single tale the Maori tell of the world's creation — but, there is a belief that every time the stories are told aloud, the world is refreshed. Each and every tribe has their own unique story, but they all share some elements: The light of our world is created from the darkness, the sky and the earth are separated, and the divine creates everything.

The gist of the story is this: The sky father Ranginui and the earth mother Papatuanuku are born from the darkness, and it's a conspiracy between their children that brings light into the world and pushes the parents into their own separate realms. After the retreat of their parents into the earth and sky, the children go on to become the rulers of their own domains. One goes to become the sea, another the forest, and so on.

Exactly how the children separate their parents varies by the telling, and interestingly, not all of them feature a supreme deity. The Maori god-of-all is called Io, and instead of being the driving force behind centuries of creation stories, he only shows up in the late 19th century. Some scholars suspect he was a modern invention added into Maori stories to give the belief system a figurehead that could be related to Christianity's God, and while he's been pretty popular, his inclusion isn't absolute.

The Cherokee world that came from water

In 1888, the anthropologist James Mooney wrote one of the first books on Cherokee culture. According to the National Endowment for the Humanities, one of the first things that struck him during his time living with the Cherokee was the importance of water to not only their daily lives, but their stories.

There's a very good reason for that, and that's the fact that according to their creation myth (via Lumen), the animals once lived in a realm far above what's now our own. Everything was water at this time, but it was getting so crowded that the animals sent the grandchild of the Beaver, the Water Beetle, down to see what he could see. The Water Beetle dove deep underwater and started bringing up bits of mud that grew to become the land.

The land wasn't dry, though, and the Great Buzzard flew down to see if it was safe for all the other animals. He reported when it was safe, and when all the animals descended, it was into darkness. The first attempts at putting a sun in the sky didn't go so well, and it was only after raising the sun seven times, they got it just right. The land was then suspended from the sky by four long cords, one at each of the cardinal directions. Someday, the cords will break and everything will be water again.

The Dreamtime of Australia's original people

Christine Judith Nicholls, a senior lecturer at Flinders University, says (via The Conversation) that not only is the creation myth of the Aboriginal People of Australia not at all well understood by those outside of the culture, it's even poorly translated as The Dreaming, or The Dreamtime. Unlike other creation myths that talk about the beginning of time, The Dreaming happens at all times, in all places. Anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner put it this way: "One cannot fix The Dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen. ... [Non-Aboriginals] shall not understand The Dreaming fully except as a complex of meanings."

Before British settlers landed on the shores of Australia, it was home to a wide range of different groups that had somewhere around 250 unique languages... which gives an idea of how diverse the creation mythology is. Common Ground says that some of these stories have been passed down through 65,000 years' worth of generations, and they often connect the Ancestral Beings with nature and ultimately, people.

The stories are as beautifully diverse as the people who tell them, and (via Australia) range from the birth of the Tjoritja mountains from piles of caterpillars to a giant cod who, while fleeing a hunter, carved a river through the land. Some places have more than one story told about them. Bottom line: 65,000 years of stories aren't easy to translate.

The Hopi emerged from the darkness

While many creation myths start with the formation of the sky and the land, then the birth of the people, the Hopi story is a little different.

Their creation myth says (via PBS) that originally, they lived deep beneath the earth. When they finally made their way upwards to the surface, they found the world being watched over by a caretaker named Maasaw. Maasaw — also the creator of the world — told the newly emerged Hopi that he had made the earth for them as a divine gift, and instructed them, "To find your home, you must find the center place."

So, the clans walked, and walked, and walked, wanting to become one with their new home — a journey represented by the spiral frequently seen in Hopi art. Finally seeing a bright sun in the southwest sky, they knew it was the sign that they had been promised: They were in the home that they had promised to protect.

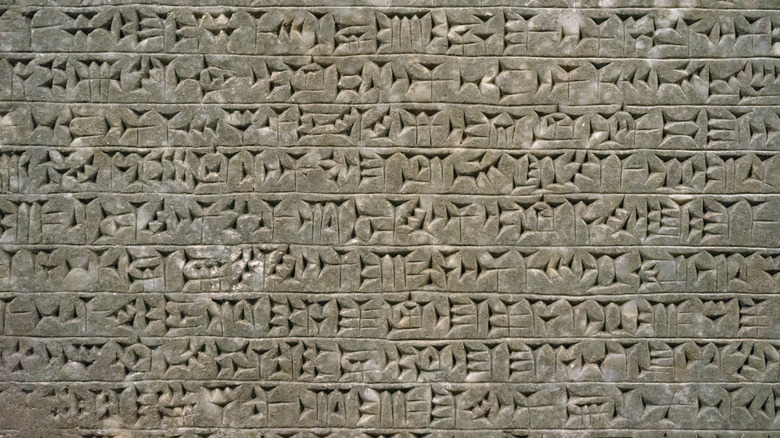

The oldest creation myth ever written

According to Learn Religions, the Enuma Elish is the oldest creation myth that's ever been found written down. It was discovered inscribed on a clay tablet in what was once one of the greatest cities on the earth: Babylon. And strangely, it's been compared to the Book of Genesis, even though the Enuma Elish predates the Bible by hundreds of years. It's not certain just when it was written down — or for how long prior to the recording it was told — but it's thought to come from somewhere in the second millennium B.C.

It starts, says World History, with the birth of water from chaos: the salty waters of Tiamat, and the fresh waters of Apsu. They give birth to children, who — as children do — are constantly interrupting Apsu's work. Apsu decides to kill some of them, but before he can, Tiamat warns her oldest of the impending conflict.

Her oldest son kills Apsu and kicks off a war between the older and younger generation of gods. Finally, the storm god Marduk defeated Tiamat, and from her body, he created the sky, the earth, and everything on it, in order to reign over this new land as a supreme being. He needed creatures to serve him, though, so he took the blood of the fallen Tiamat and of her husband, Kingu, and made man.