Who Really Wrote The Declaration Of Independence?

The Declaration of Independence is, like the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address, one of those seminal pieces of American history whose words make up the narrative of the American experience. Written in 1776, the document was intended to explain to Britain exactly why the colonists were rising up against their colonial rulers, contained an explanation of their beefs with the king, and laid out the reasons why the colonists considered themselves independent states rather than colonies, as History notes.

The scope of the Declaration's message resonates even beyond the borders of the United States. For example, as a young boy, Sigmund Freud was so moved by the document's words that he hung a copy of the text from the wall in his bedroom, as Psychology Today notes.

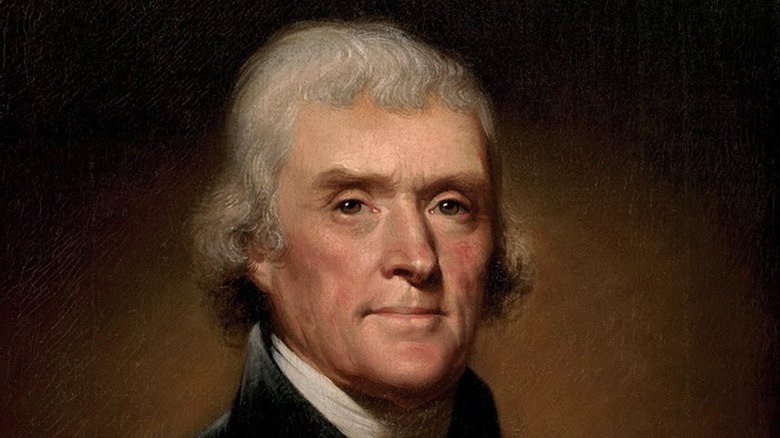

For centuries, American schoolchildren have been taught that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration. While that is true, up to a point, it's not the whole story. What's more, the text's authorship was initially kept under wraps for political reasons.

Jefferson wrote most of the Declaration of Independence

Officially, according to the JSTOR, Thomas Jefferson was merely one member of a five-person committee tasked with writing the Declaration of Independence, the others being John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. However, Jefferson was considered the most competent writer of the group, and he did most of the groundwork by writing several drafts, the last of which was edited by the rest of the committee, and later by the Continental Congress as a whole. Indeed, according to the Library of Congress, Jefferson was rather salty about some of the edits, including the excision of an entire, lengthy paragraph.

It wasn't until a few years had passed before the public became aware that Jefferson had written most of the document, and even so, the third president himself deflected attention about this subject, owing to 18th-century political culture that favored humility. Further, though he admitted authorship later in his life, he continued to deflect, noting that the ideas in the document weren't his own, but belonged to earlier philosophers such as Locke and Montesquieu.