The Mythology Of Freya Explained

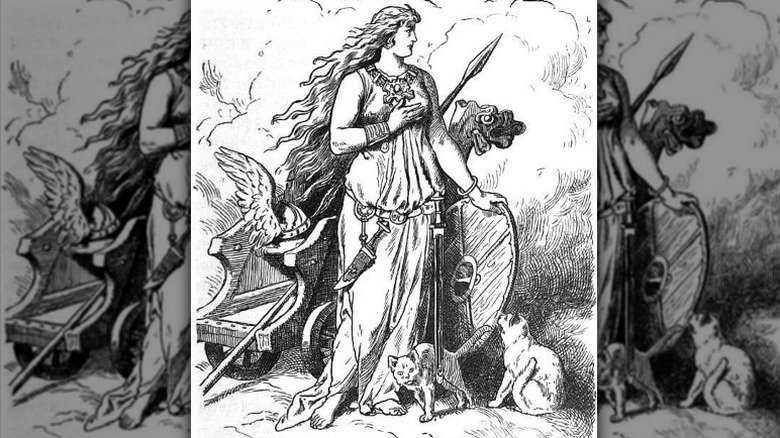

The Nordic goddess Freya mostly appears in Scandinavian mythology, more specifically in many Icelandic sagas, 13th century texts written by Snorri Sturluson, and other archaeological sources. She is the goddess of life, death, and war. Attractive and beautiful, she rides around with the help of cats and visits the underworld often, to gather prophecies and visions. She knows her magic, is a master of sacrifice, and can spin a yarn to foresee the future. She also dominates fertility, sex, and love, which makes her one of the friskiest goddesses in Norse culture. She likes to have fun but is fiercely independent, an emblem of a wild woman.

The original meaning of Freya became distorted when Christianity took over Scandinavian and German areas between the eighth and 12th centuries. As in many other areas, paganism became interlaced with Christian teaching, often masking the first under the ritual of another.

Many interpretations of Freya's nature were written after Christianization, and much of Freya's initial power and vigor was lost. With censure of everything that was associated with women and their rights, turning it into something evil, Freya had to remain hidden for many centuries. Her symbols, celebrations, and teachings became forbidden, transforming her into a woman known for infidelity and weak morals. Like Mary Magdalene, her female essence was seen as a threat to patriarchy, fully subjecting women. Here is the mythology of Freya explained.

Freya has a twin brother

According to Norse Mythology for Smart People, when Njord, one of the main gods of the Vanir tribe, married his sister, twins Freyr and Freya were born.

Norse and Germanic tribes adored Freyr for the abundance he shared. One could find the signs of him in a plentiful harvest, big family, or a hefty paycheck — basically anything that was plenty and generous. He lived among the elves and owned a ship, which could be tucked up in a tiny bag. Freyr was often depicted as riding on a boar. He had a huge sexual appetite and had many lovers among the goddesses, even his own sister, Freya. This was considered normal among the Vanir people.

As written in "The Ynglinga Saga," when Odin, the king among the gods, fought against the Vanaland people, the war was long and tiring. With many sacrifices on both ends, the enemies decided to make peace by exchanging their best men. The Vanaland people sent Njord and Freyr but felt they were deceived, since the people of Asaland sent men who weren't exactly the best of the best. Several twists later, Odin decided that the best place for Njord and Freyr were as priests, and Freya, being very knowledgeable of magic rituals, joined them. Freya became the priestess of sacrifices, carefully teaching the Asaland people how to make offerings to the gods in accordance with the Vanaland culture.

All the ladies are named after Freya

After Freyr's death, Freya was the only one who remained of the gods, as per "The Yngling Saga." When Freyr was dying, his closest companions hid this from the Swedish people to not disturb them and their peaceful, abundant lives. They continued to offer him sacrifices and did so long after they realized he was gone. Some of this love and devotion was transferred to Freya, the remaining deity. People loved Freya so much, they decided they would call all respectable women after her, so her name became to also mean "a mistress over her property" and "lady."

Since Freya was a goddess of many different nations and tribes, her name was often spelled differently — and so are the expressions for a lady in various languages. For example, in German-speaking areas, this could be frau (via Mythopedia). It is also possible to find the word with similar language roots in the Old English expression for lord (frea) and Middle Dutch expression vrouwe (woman or wife), as per the Online Etymology Dictionary. According to Nordic Culture, Freya could be spelled in various ways, such as Freyja, Freja, Fröja, or Frøya.

She was often called by different names, such as "the giver," "lady of the slain," "sea shaker," and many others.

She is a shaman and a seer

As written by Kevin Crossley-Holland in "Norse Myths," Freya was closely connected to the kingdom of the dead. For that reason, people perceived her as a shaman and a seer, being able to move between the worlds of the dead and living. As Crossley-Holland notes, the women of the sagas had the ability to fall into a trance to "obtain hidden knowledge" for the benefit of their community. Freya was the first who taught the Aesir people these powers, so her influence is reflected in these stories.

According to Mythopedia, Freya held the sacred knowledge of seiðr, a special magic ritual that allowed seers to foretell and even change the future. As explained further by Eldar Heide, seiðr was a practice that involved sending out energy with the mind to obtain "desired objects, persons, or resources." This energy could manifest in visible form as well, called gandr, such as in animal or some other form.

Archaeologist Neil Price writes that the ritual was popular all across Scandinavian countries during the late Iron Age period. Many cultures perceived the ritual as sorcery or cult practices (via Yale), since god Odin was deemed to be the "supreme master" and Freya his teacher. As Yale explains, "it is true to say that the corpus of Icelandic sagas, skaldic verse and Eddie poetry is saturated with references to sorcery in general, and seiðr in particular."

She owns special jewelry

Freya is often associated with a beautiful necklace made out of pure gold and fiery amber. As C. Scott Littleton details in "Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology," the beautiful Brísingamen was crafted by dwarfs, the artisans of Norse universe, according to the World History Encyclopedia.

The Icelandic short saga, "Sörla þáttr," written by Snorri Sturluson, describes how Freya got this most important symbol. As Littleton tells, Freya encountered four dwarves on one of her hikes. When she saw the necklace, she became obsessed with it, asking the dwarfs what the price for it would be. They responded the only way she could obtain the necklace was by spending the night with each of them. Unable to get the jewelry out of her mind, she accepted the proposal and spent four days and four nights with the dwarves.

Loki, the trickster god, somehow found out about secret Freya's necklace. When he told Odin about Freya's adventures, Odin demanded to see the necklace. Loki turned into a flea, bit Freya during her sleep, and stole the necklace. In demanding its return, Freya agreed to start a war between two kings.

She travels around on a carriage pulled by cats

Freya was a busy woman, being a warrior and a shaman, so it stands to reason her mode of transportation would be just as fantastical as she is. Legend has it that she traveled with her own glittering carriage, pulled by two male cats.

As written by William P. Reaves for Germanic Mythology, there is a lot of mystery surrounding Freya's cats, and the idea that Freya drove around in a carriage pulled by cats was not accepted easily by the male scholars of the 19th century. A reason for this is that Freya's means of transport isn't mentioned in the Poetic Edda, the original source of these legends. The first time her chariot is mentioned is in Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson's version of the stories. While the writer uses the word köttum on one occasion, meaning cats, he uses fressa on another one. Because the word fressa could be translated as a bear, confusion arises.

It should be noted that by the time these scholars tried to unravel this cat enigma, the idea that cats were evil and connected to witchcraft was already firmly planted, Reaves notes. Because Freya was associated with sorcery, cats seem the most likely to pull her carriage.

Cats often represent femininity, divinity, secrecy, capriciousness, and independence, according to researcher and therapist Ae-kyu Par – all things associated with Freya's nature.

Freya owns a falcon feathers coat

Among other magical objects, Freya owned a special falcon coat. According to "The Norse Myths," by Kevin Crossley-Holland, her falcon skin enabled her spirit to shapeshift into a bird, journey to the other world, and bring back "prophecies and knowledge."

Freya's coat was a salvation, since flying was a useful skill to have. The Prose Edda tells the story of Loki and Odin coming across a herd of cattle while searching for food. However, the two gods could never fully cook the meat, despite the hot fire they were using to roast their meal. As it turns out, the fire was being controlled by a giant, Thjasse, in the shape of an eagle. The two made a deal with the giant, who ultimately helped himself to the best parts of meat. This angered Loki, who then attacked the giant, getting himself dragged along in the process.

In an attempt to save himself, Loki made another deal with Thjasse, promising to being him goddess Idun and her apples of youth. But with Idun and her apples gone, the gods started to age, so they pressed Loki to bring her back. He borrowed Freya's falcon coat to rescue Idunn. But Thjasse followed him back to the kingdom of Asgard, and gods waited for him near the fortress wall. Once Loki and Idun were safely inside, Thjasse was caught in a trap, catching fire in his eagle form and unable to escape. The gods slayed him and saved the kingdom.

Originally, she was the goddess of war

Initially, Freya was known as the goddess of war. According to "The Norse Myths," by Kevin Crossley-Holland, Freya often rode to battle on her cat carriage, as written in the poem "Grímnismál." The end of the poem notes her warrior face, full of victory and courage. Other references to her warrior status include her association with Hildisvini, a battle boar, as mentioned by Crossley-Holland.

In the Prose Edda, she's commended for accompanying warriors after they die heroically in battle. Only those who are chosen by Freya can enter paradise to enjoy their afterlife: "Folkvang it is called, and there rules Freyja. For the seats in the hall half of the slain she chooses each day; the other half is Odin's."

As written in the Ynglinga saga, Freya also played an important part in the war between the Aesir and Vanir people. As a main deity of the Venir people, when peace was finally achieved, she brought harmony to the nations by guiding sacrifices, which helped maintain fertility cycles and life in general (via Mythopedia).

Supposedly, she had a lively sex life

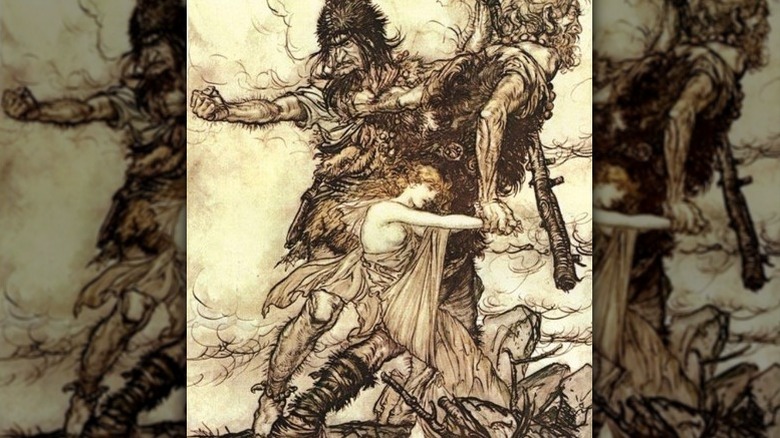

A lot is written about Freya's lusty sex life, and she has served as an inspiration on many paintings through art history. She's often portrayed as a young beautiful woman, which helped to stir the imagination of interpreters.

According to Norse scholar Daniel McCoy, Freya is known somewhat as a "party girl" and a " a passionate seeker after pleasures and thrills," ruling over the realms of love, beauty, and fertility. Accused of infidelity on many occasions, often by the trickster god Loki, she was blamed for cheating on her husband Ódr, sleeping with her brother Freyr, and messing around with the elves.

But it was not only her freedom-loving nature that got her in trouble — it seems her beauty was so immense, it often captivated other mythological creatures, or even served as a bait in different shenanigans the gods indulged in. In one of the stories in the Prose Edda, a hill giant offered to build a fortress for the gods in a short amount of time. His payment? Freya's hand, along with the moon and the sun. As Mythopedia also details, the giant was working so diligently that the gods decided to trick him so they wouldn't have to meet the agreed-upon terms. With the help of Loki and Thor, Freya was saved from an "unwanted marriage."

Freya or Frigg?

There are many debates among academics whether there are two goddesses or only one. The reason for this confusion may be dependent on the area and time period of research.

According to Norse scholar Daniel McCoy, the two goddesses are more than likely the same, with their distinction as two separate characters basically attributed to "the Norse [being] in the process of splitting into Freya and Frigg sometime shortly before the conversion of Scandinavia and Iceland to Christianity (around the year 1000 C.E.)." He goes on to argue that both are often associated with love and desire, are known for their infidelities, possess magic, and own a falcon feather cloak. In his discussion, McCoy takes a firm stance that they are "ultimately the same goddess."

Stephan Grundy in "The Concept of the Goddess" takes a bit more of a pragmatic approach, stating it may be difficult to discern due to the "scantiness of pre-Viking Age references to Germanic goddesses, and the diverse quality of the sources." He notes some of the same similarities as McCoy, also identifying the story of Freya/Frigg cashing in their bodies in exchange for a beautiful necklace. Of their differences, he writes that while Freya is wild and free, Frigg is known for her virtue, as a mother figure, and keeper of the home. Grundy also details that Frigg is connected to the Aesir people, while Freya is firmly rooted among the Vanir. "This firmly rooted distinction of race between Freya and Frigg would seem to establish them as basically different in kind as well as in person," he writes.

A lot of Freya's original power was diminished through Christianity

Today's explanations of Nordic myths are often based on interpretations, not original texts. These interpretations are heavily tainted by opinions and beliefs of writers, which were very different from the original Viking society. "Freyja's erotic qualities became an easy target for the new religion, in which an asexual virgin was the ideal woman ... many of her functions in the everyday lives of men and women, such as protecting the vegetation and supplying assistance in childbirth were transferred to the Virgin Mary," writes Britt-Mari Näsström in "Freya, the Great Goddess of the North." The author notes that the goddess was often called derogatory names by clergy and Christians.

Christianity at the time praised modesty and chastity. So when Christianity took over Scandinavia, many local myths, as in many other places, were transformed and censored to portray the gods as "lifeless idols" and "demons," writes Näsström. According to the National Museum of Denmark, old beliefs were "reinterpreted." With this censorship came a change to Freya's narrative. Patriarchal views of women did not allow her to be independent, free, and alive but turned her into another frivolous goddess or even a witch, connected to even the devil himself, as per "Lucifer, The Devil in the Middle Ages," by Jeffrey Burton Russell.

Friday is named after Freya

According to "The Stories of Months and Days," by Reginald C. Couzens (via Sacred Texts), while it is not clear whether Friday is named after Freya or Frigg, it was definitely named after one of those two. Similarly, Romans named Friday after Venus, goddess of love and beauty — both also attributes of Freya. In pagan times, people saw fertility as something extremely important. And, with Freya associated with fertility, as the Huffington Post notes, it make sense that she would be celebrated with a day of the week.

As per "Panati's Origins of Everyday Things," by Charles Panati, there are some theories that superstition around Friday the 13ts originates in Nordic myths. After Christians colonized Scandinavian countries, they converted Freya from being a goddess into a witch and believed that she, the devil, and 11 other witches met every Friday to plot the evils for upcoming week.

The Huffington Post also notes that the number 13 itself was also closely connected to feminine goddess energy in pagan times, since the average woman has 13 menstrual cycles in a year, which relates to 13 moon cycles. Astrologer Tanaaz Chubb (via Forever Conscious) notes that Friday the 13th was known as the "day of the goddess," a bridge between death and life itself. However, patriarchal religions erased this from the society, and as Vice reports, made women feel ashamed, thus perpetuating the notion of bad luck.