What It Was Really Like Being A Black Student In An Integrated School

Although the United States Supreme Court ruled segregation unconstitutional in public schools with Brown v. Board of Education, public schools in the United States remain largely segregated. There are also vast discrepancies between the schools, with school districts that are predominantly white collectively get $23 billion more per year than school districts that are non-white.

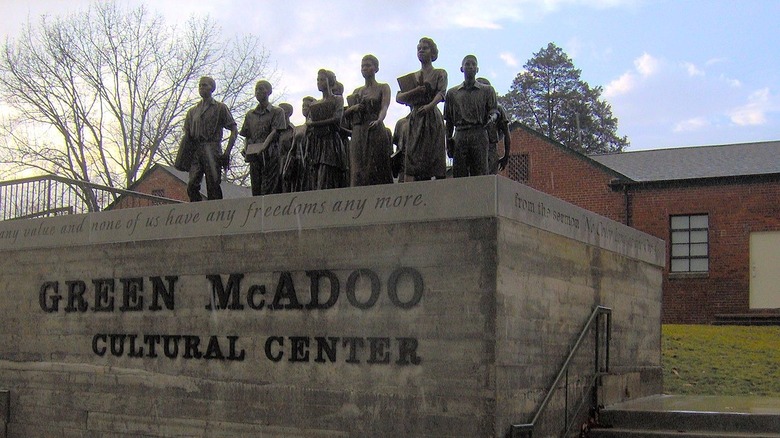

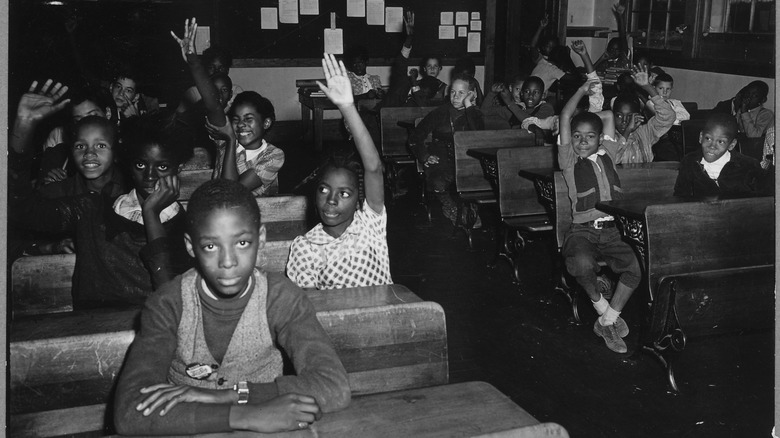

As the battle for school integration continues into the 21st century, it's worth looking back on some of the first Black students who were part of school desegregation in the 1950s to the 1970s. Many of the Black students who were part of integration are still alive today, as are those who harassed and abused them, and the things they experienced aren't part of some distant past.

Occasionally, there would be a white teacher or white student at an integrated school who didn't adhere to racist ideologies. But in general, every Black student who was part of desegregation encountered some form of abuse from the resident white population, whether it was the parents, the students, the teachers, or the school administrators. This is what it was really like being a Black student in an integrated school.

A disordered transition

In 1954, the Supreme Court's ruling on Brown v. Board of Education found that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. However, this ruling didn't mean that schools were suddenly segregated and integrated overnight. White Americans fought integration in public schools through a variety of means, and some places like Little Rock closed high schools during the 1957-1958 school year instead of integrating them, according to "Making America, Vol. II." This resulted in the Supreme Court ruling of Cooper v. Aaron, which kept state authorities from interfering with desegregation "either directly or through strategies of evasion."

However, in 1974, Milliken v. Bradley allowed segregation to remain and reemerge in the form of school district lines. NPR reports that while suburban districts didn't deny the fact that their schools were segregated, they maintained that this wasn't due to discrimination and that "school district lines had been drawn without malice." When the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that since the suburbs "weren't actively hurting" students, then they "couldn't be forced to help them either." As a result, federal courts couldn't compel these communities to desegregate.

Meanwhile, federal redlining and restrictions on house sales based on racism made it incredibly difficult for Black families to move to the suburbs, which meant that their children continued to be segregated. In his dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall described the Milliken v. Bradley ruling as a "giant step backwards."

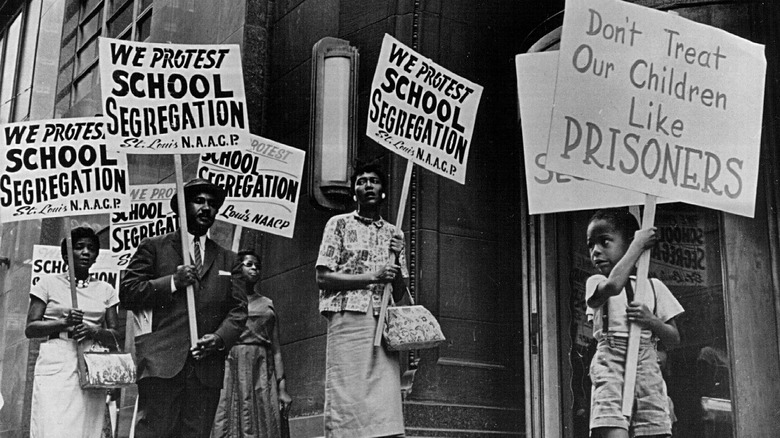

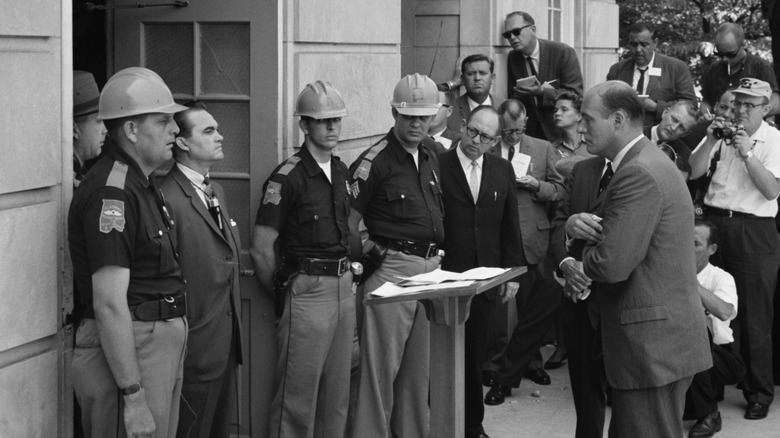

Protestors outside the school

Across the United States, white Americans came out to protest once integration was introduced in public schools. The Little Rock Nine is one of the most famous cases, when nine Black teenagers — Thelma Mothershed Wair, Minnijean Brown Trickey, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, and Melba Pattillo Beals — were the first Black students at Little Rock's Central High School. According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Guard even helped "a belligerent mob" prevent the nine Black students from entering the school.

The Little Rock Nine were supposed to start school on September 3, 1957, but they wouldn't be able to enter the school until September 23rd. But even then, after just three hours, the students were sent home as an "angry crowd gathered and tried to rush into Central High." It wouldn't be until September 25th, when U.S. Army troops arrived to escort the Little Rock Nine to class, that they were able to regularly attend Central High.

When 6-year-old Ruby Bridges became the first Black student at the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana, she'd have to cross the picket line of protestors in front of the school every day. Although the crowd slowly grew smaller and smaller, Bridges remembers that "they lasted the whole year." Sometimes, the crowd of protestors would even bring a box resembling a coffin with a Black doll inside of the box.

Mostly white teachers

Although schools across the United States were compelled to integrate students, there wasn't a similar mandate to integrate teachers. As a result, almost all of the teachers that remained at integrated schools were initially white. According to the National Education Association, tens of thousands of Black teachers and principals who taught at Black-only schools were dismissed, demoted, or forced to resign after Brown v. Board. This occurred because "many white superintendents in the southern U.S. who were against integration in the first place were unwilling to put Black educators in positions of authority over white teachers or students." This continued into the 1980s as over 20,000 Black teachers lost their jobs between 1984 and 1989. Although some Black educators were eventually hired, the disparity continues in 2021.

Some ended up with teachers who were outright cruel. Ruth Carter recounts how her sister Pearl was part of integrating A.W. James in Mississippi and the teacher working with Pearl would "hold her nose when she'd stand over her." Theodore Adams, who was part of desegregating Orangeburg High School in South Carolina, was laughed at by a teacher after reporting physical abuse from other students.

For some Black students, limited interaction from teachers was the norm. Hull Franklin recalls how at Marks High School in Mississippi, the most common interaction with a teacher amounted to "Ok you here follow along if you can. If you can't catch up, who cares? I don't want to deal with you."

Pulling white children out of school

On her first day of school at the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Ruby Bridges was taken directly to the principal's office. She wouldn't be taken to her classroom until the second day, at which point she realized that the building was essentially empty. "I remember thinking, you know, my mom has brought me to school too early. There's no one here. But that went on for months. Being in an empty classroom just my teacher and myself, I constantly was trying to figure out why was I the only child in the whole school," Bridges recounts to NPR.

According to "The Jim Crow Encyclopedia," edited by Nikki L. M. Brown and Barry M. Stentiford, many white parents pulled their children out of public schools and enrolled them instead into private schools, which popped up across the country during the 1960s and 1970s and "continue to be segregated both racially and along class lines."

At some places, like the Sturgis Consolidated School in Kentucky, parents claimed that they kept their students out of school due to the presence of the National Guard. However, the National Guard had been called there only because a group of white farmers and miners had previously prevented nine Black students from attending class, per Sturgis And Clay.

Verbal abuse in class

As Black students were integrated into previously all-white schools, they faced a barrage of racist verbal abuse. Remember getting a book in class and finding "turn to page 52" on one page, which led you to another page and another until there was a note? Crystal Giddings followed one such handwritten note to find a paragraph that read "you black and ugly, dumb and stupid go back to Africa," followed by a racial slur, in her school in Atlanta, Georgia per the National Education Association. Henry "Fred" Guinn remembers at Oak Ridge High School in Tennessee, one morning he came to school to find "Go home, n*****" written on the cafeteria wall. But before other students arrived, the wall was wiped clean and there were no further incidents like that one.

According to "Troublemakers" by Kathryn Schumaker, at Neshoba Central School, Pennsylvania, white students harassed the 42 Black students so much during the 1966-1967 school year that the following year there were only 11 Black students attending Neshoba Central School. "Within three years, only one black student remained at the school." In 1972, legal scholar Derrick A. Bell noted that "Black children are harassed unmercifully by white students."

Black students weren't the only ones subjected to verbal abuse. In New Orleans, white mothers known as the "cheerleaders" screamed verbal abuses and pounded on the cars of both Black and white parents who continued taking their children to school, per the "Encyclopedia of African American History" by Paul Finkelman.

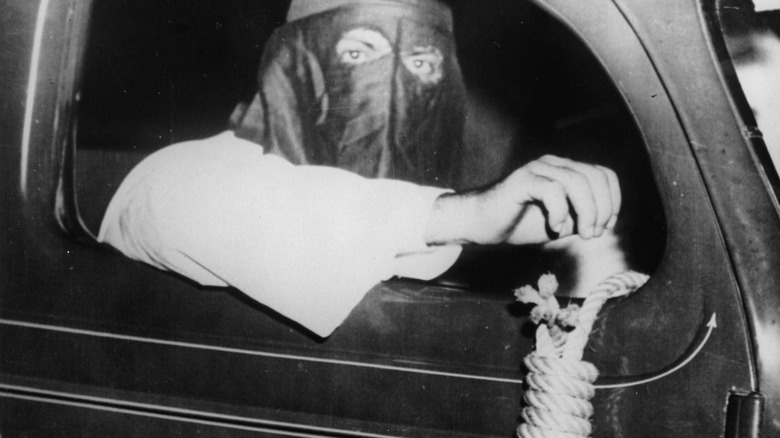

Threats of lynchings

Black students who participated in integration were often threatened with lynching. WRAL reports that when Joe Holt Jr. applied to attend the all-white Josephus Daniels Junior High School in 1956, his family became suddenly subjected to constant phone calls through the night for years, threatening to kidnap and lynch Holt. In the end, his applications were delayed and delayed until Holt graduated and went on to college.

When up to 400 white people surrounded Mansfield High School in Texas to prevent three Black students from enrolling, they attacked reports and "hanged the three black students in effigy" according to Black Past.

When Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine, walked into school, she'd pass a crowd of white protesters yelling "Lynch her! Lynch her!," per "Making America, Vol. II." In Ebony Magazine, Eckford recalls looking for a friendly face or someone who might help her, but found only an elderly white woman who spat on her. The National Guard officers also offered no help, so Eckford started walking to a nearby bench at a bus stop. But upon sitting down, the mob followed her and someone started shouting "Drag her over to this tree! Let's take care of this n*****."

Bomb threats and urine-filled bottles

In addition to lynching threats, schools that integrated received numerous bomb threats. After Millicent Brown's 1963 court case Millicent Brown et al v. School District 20 led to the desegregation of Charleston public schools in South Carolina, Rivers High School received three bomb threats on her first day of school on September 3, 1963, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Carol Watkins recounts how in Birmingham, Alabama, before the schools were even integrated, bomb threats would be called in to the all-Black high school and when the Black students were outside, white people would drive by "and throw Coke bottles filled with urine."

In 1957 in Nashville, the KKK called and threatened every Black parent in Nashville who registered their child at a white school.

But unfortunately, they weren't always just a threat. When Hattie Cotton Elementary School became integrated in September 1957, they admitted one Black girl, 6-year-old Patricia Watson. After the first day of school, shortly after midnight on September 10th, an explosion rocked the elementary school, as someone threw dynamite at the building from a moving car. Thankfully, since it was so late at night, no one was injured. But although John Kasper was arrested for the mob he rallied that night, no one has ever faced criminal charges for the actual bombing, per Tennessean.

Steered away from AP classes

Although the schools were integrated, they'd continue to maintain a "partial internal segregation." By herding white students into Advanced Placement classes and steering Black students away from them, schools were able keep the school virtually segregated. As Leland Ware notes in "A Century of Segregation," "the talented and gifted programs became the reserve of affluent white students."

According to "With All Deliberate Speed," in Hayti and New Madrid in Missouri, Black parents claimed that putting the majority of Black students in "special education classrooms produced a new variety of segregation." The Washington Post reports that one woman who is now a social worker recalls how her teacher even tried to get her transferred from the school by claiming that she was mentally disabled.

According to "Invisible Enemy" by Greta de Jong, the practice of separating students based on academic ability is known as "tracking" and has been found to be "related more closely to race than to academic ability." Meanwhile, a study of New York City public schools in the 1970s found that the criteria used to put Black students in non-honors classrooms was "vague" and "subjective." One study also noted that "school districts have been willing to trade off Black access to equal education opportunities for continued white enrolments in the school system."

Physical attacks

Amidst bomb threats and verbal abuse, many Black students faced physical harassment and abuse as well. At almost any moment a white student would try to trip, kick or assault the Black students in some way and U.S News and World Report says that Black girls often received more abuse than Black boys.

Melba Pattillo Beals, one of the Little Rock Nine, faced near-daily assaults. While it was typically kicking or spitting, in an interview with NPR, Beals recounts how one day, a boy with a plastic toy gun shot acid into her eyes and face. It was only because her bodyguard immediately raced her to a water fountain and ran her eyes under water that Beals didn't lose her vision.

Minnijean Brown, also part of the Little Rock Nine, was attacked by a white girl in February 1958. Brown responded by calling her "white trash," and in the end, Brown was the one who was expelled. The white students were emboldened and some started wearing buttons that read "One down and eight to go," per "The Shadows of Youth" by Andrew B. Lewis.

Accused of wanting to be white

Some Black students who were integrated into white schools found that it ended up affecting their relationships with their Black peers. Lucy Brenda Patterson Frinks recalls how after she was integrated into Abbeville High School in South Carolina in 1967, she lost virtually all of her friends because everyone saw her as wanting to be white: "When I would try to go to the football games for the predominantly Black school, nobody wanted to sit with me. Nobody wanted to hang out with me."

Millicent Brown had a similar experience while desegregating Rivers High School in South Carolina. One time while visiting her boyfriend's basketball game, at his all-Black high school, the girls there said to her, "What are you doing here? You knew you always wanted to be white anyway."

Michael J. Klarman writes in "Brown V. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement" that ultimately, few would end up holding out and many Black students ended up returning to all-Black schools after attempting to desegregate all white-schools.

No guidance from the school

The teachers weren't the only ones who neglected their Black students. Guidance counselors also did the absolute bare minimum. Emma Harvin recalls how at Edmunds High School in South Carolina, the guidance counselor only told them what classes to take and never mentioned "These are the colleges; what you need to do; or where you need to go" or "this is your weak point and this is your strong point." Harvin believes that if they'd gone to an all-Black school, they would've known about college applications and scholarships and their options for Black colleges.

At Abbeville High School in South Carolina, Lucy Brenda Patterson Frinks describes how the guidance counselor would sign necessary forms but offered no guidance in the way of SAT information or paperwork help: "If you didn't know about it, then you were lost."

As with the dismissal of Black teachers and principals, Black guidance counselors were also part of the wave of dismissals. According to "The American South in the Twentieth Century," between 1954 and 1964, up to 38,000 Black teachers and administrators lost their jobs. As noted by the National Education Association, as a result, Black students lost a majority of their advocates in the school system.