Who Was Really Behind The Assassination Of Park Chung-Hee?

Park Chung-hee was no stranger to deadly assassination attempts. There were several attempts on his life, one of which occurred on August 15, 1974, when Mun Segwang tried to assassinate President Park in the National Theater in Seoul. However, while none of the bullets hit Park, his wife, Yuk Young-soo, was mortally wounded by the bullet meant for her husband. And in the gunfire between Mun and Park's security guard, a gunshot hit and killed a high school student, Jang Bong-hwa.

But no matter how used to assassination attempts one might be used to, it's impossible to guess what flashed through Park's mind when he realized that he was going to be assassinated by someone he thought he could trust. Was it a crime of passion or was this something that had been in the works for years? And unfortunately, it seems as though Park wasn't the only one left in the dark.

It's easy to find the culprit red-handed and consider the case solved. But the motivations that drive people are often less straightforward than one might imagine. And how does one even go about figuring out the motivations behind an assassination if no one's willing reveal themselves? This is the story of who was really behind the assassination of Park Chung-hee.

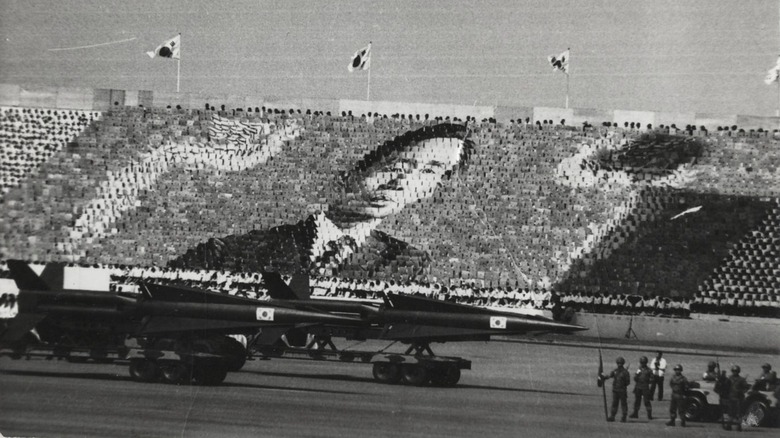

Who was Park Chung-hee?

Park Chung-hee, also written Pak Chŏng Hŭi, was born to Paek Namui and Pak Songbin in Sangmo-ri, a village in the Province of North Gyeongsang, Korea on November 14, 1917. In "Korea's Development Under Park Chung Hee," Hyung-A Kim writes that Park came from a financially insecure family and was the youngest of seven children.

At the age of 15, Park entered the Taegu Teachers' College, a school sponsored by the Japanese colonial state, which sought to create "Japanized" teachers. However, according to "Post-War Korean Conservatism, Japanese Statism, and the Legacy of President Park Chung-hee in South Korea," there was limited success in "Japanizing" students and those who went on to teach would end up trying to "arouse [their] students' nationalist sentiments," just as Park did at Mun-gyeong Common School.

In 1940, Park resigned from teaching and instead joined the Japanese Manchurian Military Academy. He would end up staying in Manchuria until 1945. With the collapse of the Japanese Empire, Korean soldiers in the Manchurian or Japanese Army joined the Korean Liberation Army instead.

Rising through the ranks of the army, the April Revolution provided the catalyst that Park needed to seize power. And on May 16, 1961, Park organized a military coup d'état that put him in power and brought the Second Republic of Korea to an end.

Park's Third and Fourth Republics

With less than 4,000 soldiers, Park Chung-hee and his men occupied KBS and major government institutions. By May 18, Park forced the resignation of Prime Minister Chang Myon's cabinet and created instead the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction, which was meant to be in charge until the next elections. According to "A History of Contemporary Korea," although the United States issued a statement saying that it supported the "lawful government of Korea," officials invited Park to Washington D.C. in November 1961.

Park was elected president in October 1963, although he only received less than 200,000 more votes than Yun, and on December 17, 1963, Park was sworn in, establishing the Third Republic, Jinwung Kim writes in "A History of Korea."

The Third Republic essentially became a "one-person dictatorship" ruled by Park, who built up his political power while pushing for Korea's economic development. Despite having claimed that he would restore a civilian administration, Park maintained control. Even when it came to accepting $500 million from Japan for reparations, which came in the form of public loans and interest-free commercial credit, Park did so without any "national discussion or hearings," according to the Asia-Pacific Journal.

In 1972, Park suspended the constitution and a new Yushin Constitution was implemented. According to "Post-War Korean Conservatism, Japanese Statism, and the Legacy of President Park Chung-hee in South Korea," under the Yushin Constitution, government control was highly centralized, and the president could be re-elected indefinitely. Under the Yushin Constitution, Park inaugurated Korea's Fourth Republic.

The Bu-Ma Democratic Protests

In response to the increasing brutality, repression, and censorship of the Fourth Republic, protests erupted in Busan on October 16 1979. According to "Asia's Unknown Uprisings," by October 18, martial law was declared in Busan and "anyone who looked like a student was arrested and beaten." Over 200 people were arrested in Busan alone. But within days, the protests spread to Masan, now known as Changwon, and Seoul, and they were confronted with tear gas, according to the Washington Post.

In "Protest Politics and the Democratization of South Korea," Youngtae Shin writes that over 50,000 people participated in the protests. And although the protests were started by university students, a majority of the demonstrators were regular citizens.

According to Hankyoreh, a 2018 investigation revealed that Park Chung-hee's declaration of martial law and deployment of troops was done without a garrison decree, which meant that Park violated the law when he sent the military to quell the demonstrations and told them to "take necessary measures at your discretion."

Kim Jae-gyu, head of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), would later testify that Park's chief bodyguard, Cha Ji-cheol, suggested that millions of casualties in Busan "shouldn't be an issue" and that Park was leaning towards this decision, per The Korea Times. Some even suggest that it was this method of suppression that led to Park's assassination.

What was the KCIA?

The KCIA was established on June 10, 1961 by Kim Jong Pil (Kim Chongp'il), Park Chung-hee's nephew-in-law. According to "A History of Contemporary Korea," the KCIA was organized to focus on domestic intelligence and criminal investigations. Given "massive manpower and financial support," as well as unlimited judicial power, the KCIA essentially had free reign to intervene on anything that seemed in any way to be anti-government related.

According to "Human Rights in Korea," numerous organizations found that the KCIA used horrific varities of physical torture as well as psychological intimidation. Ch'oe Hyong-u, a former opposition National Assemblyman who was temporary paralyzed as a result of the torture he experienced at the hands of the KCIA, questioned during a National Assembly why cattle dealers who forced their animals to drink a lot of water were arrested while "the KCIA and other agents who used water torture" remain free. He asked, "Are the assemblymen less important than the cattle?"

The KCIA saw little limit to its power. In August 1973, the KCIA kidnapped Kim Dae-jung, a former presidential opponent of Park, from his hotel in Tokyo and came very close to assassinating him. Kim was seconds away from being drowned, but because the KCIA had been "sloppy at their work," according to Reuters, a U.S. aircraft arrived just in time and kept the kidnappers from killing Kim. Although his life was spared, Kim was taken back to South Korea and put under strict house arrest.

Who was Kim Jae-gyu?

Kim Jae-gyu was born on March 6, 1926 in Kumi, a village in the Province of North Gyeongsang, Korea. Kim briefly became a middle-school teacher before joining the army and attending the Korean Military Academy, per Britannica. Like Park Chung-hee, Kim rose through the army, and he became vice president of the Army College in 1957.

According to a "Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Korea," Kim didn't participate in Park Chung-hee's May 1961 coup and was briefly detained based on the suspicion that he was opposed to the coup. However, Park ordered his release, and Kim went back to his army career. After serving as the minister of construction from 1974 to 1976, Kim was appointed director of the KCIA in 1976 after the KCIA's former director, Kim Sang Keun, defected, the New York Times reports.

Kim and Park reportedly met at the Korean Military Academy and were lifelong friends. However, Kim reportedly tried to persuade Park not to seek reelection after 1971, and was "unhappy" that Park didn't take his advice. Kim was also reportedly opposed to the Yushin Constitution, and expressed disagreement with the increasingly repressive measures favored by both Park and Cha Ji-cheol, though as the head of the KCIA this was a relatively ironic position to take. But regardless of Kim's prior relationship with Park, in October 1979, Kim decided to take Park's life into his hands.

A deadly dinner in a safe house

On October 26, 1979, President Park Chung-hee sat down to dinner with KCIA director Kim Jae-gyu, his bodyguard Cha, and former KCIA director Kim Gae-won at a KCIA safe house. Joining them were Shim Soo-bong and Shin Jae-soon, who were brought in to entertain the men.

According to the Korea Times, Park was reportedly distressed that the KCIA hadn't anticipated and preemptively subdued the demonstrations. When Kim claimed that the demonstrations were being held by "angry citizens" rather than "impure elements," Park reportedly had a tantrum.

The fighting escalated and around 7:40 PM, Kim stormed out of the room. Returning with a .32 caliber handgun, Kim yelled at Park "How can you have such a miserable worm as your adviser?" and shot at Cha, hitting him in the wrist. After shooting Cha in the chest, Kim's weapon jammed and he ran out of the room. Meanwhile, Kim's KCIA guards killed three of Park's presidential guards and injured another, having been told by Kim to shoot Park's guards if they heard gunfire. Kim returned with a .38 caliber gun and shot Cha in the stomach, killing him. As Shim and Shin ran out of the room, Kim walked over to Park and shot him once more behind the ear, killing him.

What was Kim Jae-gyu's motive?

While it's clear that Kim Jae-gyu was responsible for Park Chung-hee's death, the exact motive for the assassination remains unclear. According to Courthouse News, during the trial, Kim testified that he acted in order to "restore democracy and save lives" because otherwise millions might have been executed in Busan. Other theories have been suggested ranging from insanity caused by a liver disease to jealousy over Cha's closeness with Park.

According to "Famous Assassinations in World History," Kim also frequently saw CIA station chief Robert G. Brewster and reportedly met with U.S. ambassador William Gleysteen five hours before the shooting, leading some to suggest that the "CIA promoted Park's assassination." But the theories vary between premeditation and impulsive and at the end of the day, Kim is the only one who knows for sure exactly what happened.

Others, including Major-General Chun Doo Hwan, stated that Kim planned everything as early as June 1979 and had intended to make himself president using the power of the KCIA. But Kim's actions after the assassination lend little credence to this theory. Ultimately, as of 2021, the debate continues and no one other than Kim knows exactly what led to Park's assassination on the evening of October 26, 1979.

Kim Jae-gyu's almost immediate arrest

Within four hours of killing Park Chung-hee, Kim Jae-gyu was arrested. According to the Korea Times, Kim hailed a cab outside as he ran off, leaving behind the three surviving witnesses to the murder. The fact that Kim left behind witnesses is what leads some, including investigators, to think that "the murders were an act of spontaneous passion rather than part of a premeditated coup attempt by the KCIA."

According to Keesing's Record of World Events, Kim initially intended to head to the KCIA headquarters, but he ended up going to the army headquarters instead. There, Kim reportedly suggested declaring martial law and keeping Park's death secret for a couple of days. But by 11:30 that night, Kim was exposed as the murderer and was arrested. And martial law was still declared anyway. However, when the BBC originally reported this story, the government statement they cited claimed that Park died trying to intervene in a fight between Kim and Cha.

Courthouse News writes that domestic security chief Chun Doo-hwan was assigned to investigate Kim's motivations and after one week came to the conclusion that Kim was influenced by a "vain desire to become president." But within a few months, Chun was the one swooping in to take power.

Chun Doo-hwan seizes power

Unfortunately, Park Chung-hee's murder did little to change the political structure of the underlying system and after his assassination, it was easy for Chun Doo-Hwan to take over, using President Choi Kyu-hah as a brief figurehead. But according to "The Military and Democracy in Asia and the Pacific," this didn't mean that his quick seizure was easily accepted by the population. "The immense political cost of Chun's rule was manifested in the bloodshed in Kwangju (Gwangju)," it states.

As peaceful pro-democracy protests started in Gwangju in May 1980, Chun sent military forces in to suppress the demonstrators, turning a peaceful protest into a "nine-day revolt," according to Yonhap News Agency, as the military brutally repressed the protestors. Government figures state that up to 200 civilians were killed and up to 2,000 were wounded, but others claim that the death toll was as high as 2,000.

Ultimately, in 1996, Chun was found guilty of corruption, mutiny, and treason in relation to the Gwangju Uprising and sentenced to death, but he only spent around two years incarcerated, according to Reuters. In 2018, the BBC reported that the South Korean defense minister also apologized an apology regarding the numerous acts of sexual violence inflicted on the residents of Gwangju during the uprising.

What happened to the conspirators?

In addition to Kim Jae-gyu, Chief Secretary Kim Gye-won was also arrested as a collaborator in Park Chung-hee's assassination, as were four KCIA agents, the head of security of the KCIA facility, and a driver. According to the Washington Post, the charges ranged from capital murder and attempted sedition to destruction of evidence.

During the trial, news reports were typically censored and what came out put most of the blame on KCIA Director Kim Jae-gyu. In the end, Kim Jae-gyu and five other KCIA workers were sentenced to death for their part in the assassination of Park. The Korea Times reports that Kim Jae-gyu and four other KCIA workers were hanged on May 24, 1980. Another would be executed by firing squad. Seo Young-jun was also imprisoned, but was released in 1982.

Kim Gye-won was thought to be complicit partly because it was believed that he could've prevented the events, being Kim Jae-gyu's friends, but the fact that he fled from the scene and didn't immediately reveal that Kim Jae-gyu was guilty suggested that he was involved. While he was initially given the death penalty, the court decided that "he was more irresponsible than guilty" and his sentence was commuted. He also ended up being released from prison in 1982.

Seeking a posthumous acquittal

Over 40 years after Park Chung-hee's assassination and Kim's execution, Kim Jae-gyu's sister, Jung-sook, is pushing to have her brother postumously acquitted of treason. According to Courthouse News, Jung-sook insists that Kim "was executed without telling his side of the story — on why he had to do what he did." Jung-sook isn't contesting the murder charges or the death penalty that Kim was given, but she refuses to accept that Kim killed Park as an act of treason against the state.

But while little is currently known about the full proceedings of the original trial and recordings were only revealed to exist in 2020, and only exist because a security official disobeyed orders to destroy the 128 hours of tapes decades ago. In an attempt to rectify the secrecy of the original proceedings and clear Kim's name, Kim's family has requested a retrial.

According to Korea Expose, Kim has also become an "unofficial hero" for some Koreans and his grave has turned into a pilgrimage site.