The Untold Truth Of The Book Of Proverbs

Tucked away after Psalms, the Book of Proverbs might be one of the most misunderstood books of the Bible. In contrast to many of the Christian and Jewish Scriptures, which often teach history, law, or theology, Proverbs is primarily a collection of "wise sayings" — proverbs, like its title says.

In other words, unlike much of the Bible, Proverbs isn't there to tell you what you have to believe, or what you have to do; it's there almost entirely just to give you advice. "Hey you," says Proverbs, "you're doing life wrong. Not, like, sin-wrong, but just not as good as you could be doing it." The source of iconic lines like "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom," "Spare the rod and spoil the child," and "Better to live on a corner of the roof than share a house with a quarrelsome wife," Proverbs has also given a name to at least one multi-level marketing company (see: Thirty-One).

It's a book whose influence is everywhere if you look for it. But where did it come from? Who wrote it? And why is it in the Bible? Let's take a look!

It almost definitely wasn't written by Solomon

While the Book of Proverbs opens with the lines "The proverbs of Solomon son of David, king of Israel," modern scholars agree that the book, as we know it today, dates to long after Solomon's reign — which isn't to say that King Solomon definitely had no input into it, just that there were many more people involved in its composition and editing, probably over centuries. As My Jewish Learning puts it, "The attribution more likely stems from the tradition of tying a book to a biblical figure known for a certain quality" — in other words, because it's a book of wisdom, and Solomon was known for being wise, scribes attributed it to him. That's not necessarily intentional dishonesty, though — it's much more about honoring Solomon as a symbol for collective Jewish wisdom.

So who actually wrote Proverbs? It's been said that Proverbs is "a collection of collections" — that is, various scribes, over many generations, collected wise sayings, and then later editors collected their collections into the compendium we know as Proverbs. The book itself identifies multiple authors, attributing its first two sections (1–9; 10–22:16) to Solomon; its third section (24:23–34) is simply introduced as "the sayings of the wise"; the fourth section (25–29) is "other proverbs of Solomon that the officials of King Hezekiah of Judah copied." Then there are two appendices (30, 31) credited to "Agur" and "Lemuel" — two figures we know nothing about outside of the Book of Proverbs itself.

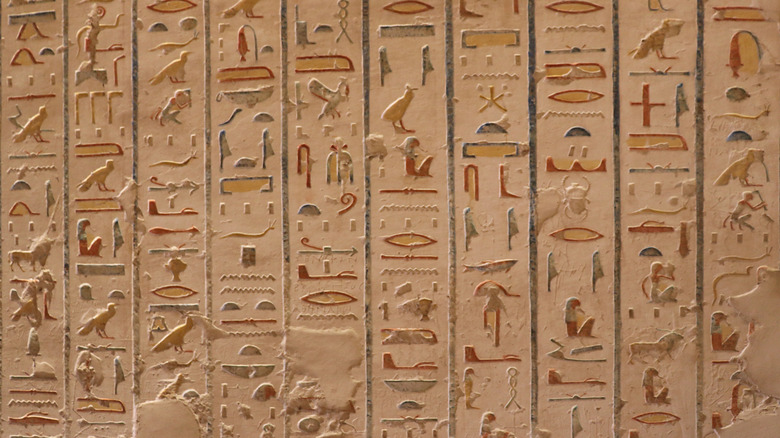

It may have been partially borrowed from an Egyptian source

As we've said, Proverbs is a collection of collections, so it wouldn't be a huge surprise to see bits and pieces of passages similar to it floating around in the wisdom literature of the ancient near east; still, there's at least one extended passage in Proverbs that has proven strikingly similar to another piece of ancient literature.

The Wisdom of Amenemope — an Egyptian text discovered in the late 19th century and eventually translated into English in 1976 — has enough parallels to Proverbs 22:17–23:11 that it's difficult to ignore. Some of the parallel verses are listed over at Got Questions: For instance, while Proverbs 22:22 reads, "Do not rob the poor because he is poor, Or crush the afflicted at the gate," Amenemope chapter 4, lines 4–5 features the similar "Guard yourself from robbing the poor, From being violent to the weak." And while Proverbs 23:5 tells us, "For wealth certainly makes itself wings; Like an eagle that flies toward the heavens," Amenemope chapter 10, line 5 reads, "They [dishonest riches] make themselves wings like geese, And fly to heaven."

It's hard to know exactly what the relationship is here — it's possible it's just a coincidence, or that Amenemope borrowed from Proverbs — but many modern English Bible translations actually defer to Amenemope when there's an ambiguity in translation — for instance, Proverbs 22:20, which was once considered nearly untranslatable, now follows Amenemope chapter 27, lines 7–8 in modern translation like the English Standard and New International Version (via Bethany Bible Church).

It was almost excluded from the Bible

There's a common perception that which books were included or excluded from the Bible was decided by a handful of random people at a single point in history but that's not really the case. The process of determining which books are in the Bible and which aren't has been much longer, messier, and more contentious than many imagine, and it's been no less so among Jews than it has among Christians. When the rabbinic college decided to determine their canon in the late first century, there were several books that were particularly controversial — and Proverbs was one of them.

Why did certain rabbis object to Proverbs? According to Harold Wilmington, the dean of the School of the Bible at Liberty University, there were two main reasons. First of all, there are several passages warning about the dangers of adultery that get pretty explicit, and second, there are several apparent contradictions. One example of the latter is the back-to-back pair of verses 26:4 and 5, which together read, "Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest you be like him yourself. Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes."

Well, which is it, Solomon? Should we answer fools, or not? There doesn't have to be a contradiction there — maybe there's a time and a place to answer a fool — but it was enough to make at least a few rabbis feel icky about it.

It's had considerable influence on Christian theology

Numerous commentators have observed that, despite the book's Jewish origins, it shares very few of the practical or theological concerns of much of the Old Testament. There are no verses warning against idolatry, for instance, and very few verses with reference to burnt sacrifices or temple worship, which has led some scholars to assert a later Greek influence on the book (via Brill).

One of its particularly Greek-seeming aspects is that Proverbs occasionally anthropomorphizes Wisdom as a goddess-like character who actively calls out to people, offering to teach them her insights. In Proverbs 8:23–31, Wisdom actually claims to have eternally coexisted with God himself, saying, "Ages ago I was set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth." This personification of Wisdom gave way to a strain of Jewish thought imagining Wisdom as co-creator of the universe with God; in turn, the Apostle Paul and the Apostle John both borrowed this Wisdom imagery to describe the eternal nature of Christ in their writings: Paul in Colossians ("He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation") and John in his Gospel ("In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.")

In turn, both these and the Proverbs passages proved pivotal when there was debate in the fourth-century church over whether Jesus was God himself or a creation of the Father; obviously, the Jesus-is-God bunch won out, mainly because of how these passages lean (via New Advent).

It's said you should read the entire book every month

According to Dr. Harold Wilmington, a proverb is "a short sentence drawn from long experience." Each proverb takes the hard lessons learned over the course of an entire life and condenses it down into a single line or two of poetry. The upshot is that, to really wrap your head around the meaning of a proverb, you often have to sit with it a while and unpack it — sometimes you have to ponder it for weeks, or even years. Wisdom, as they say, doesn't come easy.

Because of this, it's been suggested that anyone looking for wisdom from the Bible should simply read a chapter of Proverbs every day — Proverbs has 31 chapters, so you'll get through the whole book in a month (and, if you want, can continue to re-read it every month thereafter). As Theology of Work points out, Proverbs, as a collection of collections, repeats its subject matter several times, often coming at it from different angles, so if you can't make sense of some of its wisdom early in the month, maybe you'll get something out of it weeks later when the topic comes back around.

In any case, the acquisition of wisdom — like the creation of the Book of Proverbs itself — is a long and involved process. It's a journey, not a destination.