The History Of Palm Reading Explained

Palm reading has been around for centuries. It apparently originated in India, though it has been found all over the globe, most notably in Europe and Greece. The Romani people, in particular, learned and passed on the fortune telling arts, including palm reading, to the rest of the world due to their mostly nomadic nature (via Seagrape Apothecary). Modern palm readers now occasionally include psychology in their readings as well.

Palm reading is essentially using the lines of the palm to figure out a person's characteristics or future. Different features of the palm and fingers signal different signs to individual palm readers, though certain concepts are common. Palm reading has also been featured in paintings and literature throughout history.

Palm reading is a way for people to feel as though they have more of a hand in their own futures because they are able to foresee them. Though certain religions forbade divination, people still flocked to palm readers. Believing that they carry the possibility of their futures in their hands is powerful knowledge. So, let's learn more about the history of palm reading.

What is palm reading?

Palm reading, also called palmistry and chiromancy, is the art of using palm lines and undulations of the palm to divine the future and characteristics of a person. Palm reading has had periods of popularity throughout history, as well as periods of others fearing it as divination. There isn't any scientific evidence that physical characteristics of the palm have occult meanings, writes Britannica. However, the hand does show physical evidence of cleanliness, someone's occupations, nervous habits, and even hobbies. For example, guitar and bass players might have calluses on the tips of their fingers from playing constantly.

The arts of chirognomy and chirosophy go hand in hand with palmistry; the first is about finding intelligence in the hands, while the second compares the values of different formations in the hands (via Encyclopedia). Palmistry uses the elements gleaned from the first two arts to foretell future events. Palmists study the hands in general, then focus in on specific lines and markings, such as the lines of health, wealth, and happiness, which separate the hand from the forearm at the wrist. It is generally regarded as a good thing if the lines are deep, firm, and narrow. There are also different types of hands, mainly based on physical characteristics such as length and width of the fingers.

Practitioners generally give their own special attributes to different meanings or areas of the hand. Others are standard, such as the mount of Venus, which signifies a person's energy levels.

Origins of palm reading

Palm reading can be found all over the globe. In general, the origins of palmistry are somewhat uncertain, writes Britannica. Much of the practice of modern palm reading came from ancient Greece, though it was also found in China, Persia, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Tibet.

According to "Wonders of Palmistry," the Greeks Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Anaxagoras all wrote about their individual views on palmistry. One particular book, written by Hispaunus, was inscribed in gold when it was presented to Alexander the Great.

However, the fortune telling of the Romani people, which included palm reading, began in northern India; palm reading was possibly practiced by the Brahmin caste. It is likely that the Indian practice of palm reading is even older than that of the ancient Greek or Chinese practices. Indian astrologers first gained knowledge of the signs that were later used in palm reading. Samudra Rishi was the first Indian scholar to write about palm reading; he was followed by many others. Knowing about their life challenges ahead of time allowed those who had their palms read to have time to work to change themselves or the events before they happened in order to improve their life.

Romani and palmistry

The Romani people also elevated the art of palmistry throughout the centuries, even inspiring others to study it, such as American palmist William Benham. The Romani originated in the northern Indian Punjab region as a nomadic people, and entered Europe between the ninth and tenth centuries, writes Holocaust Encyclopedia. Europeans mistakenly believed they came from Egypt, and therefore called them "Gypsies." This is a derogatory term (and not just in English: the German word for "Gypsy" is from a Greek root meaning "untouchable"), which has unfortunately stuck around to this day. The Romani faced prejudice and persecution wherever they traveled for centuries, and were targeted in the Holocaust.

Between 1 to 1.5 million Romani were in Europe in 1939, writes Holocaust Encyclopedia. They spoke Romani, which is based on Indian Sanskrit. According to professional palm reader and Romani Jezmina von Thiele on the Seagrape Apothecary, palm reading equaled survival to the Romani, since it was something they could practice (and make a living with) just about anywhere.

The Romani still practice fortune telling today, and different groups are known for different practices. Truly nomadic Romani are on the decline; some have converted to either Christianity or Islam and many have ordinary jobs that have nothing to do with fortune telling. Nonetheless, families are known for their talent at specific arts. Overall, von Thiele asserts that the community is known for their creativity, resistance, and resilience (via Seagrape Apothecary).

Palm reading and the witch-hunters

People have always aimed to bring stone-cold certainty into their lives by trying to read the future in various ways. Palmistry was just one way of accomplishing that. Palm reading was popular in the Middle Ages, ironically with witch hunters. According to Google Arts and Culture, they saw birthmarks and other marks on the palm as proof of a Satanic pact. Palm reading allowed them to find further signs of witches and apply those to their work. Medicine wasn't so advanced yet as to convince people living in rural areas that a series of moles on the back of the hand were harmless. No, it must be the work of the devil; it couldn't possibly be anything else.

Nevertheless, the practice's popularity continued, albeit with some skepticism. At the time, female Romani soothsayers, known as "drabadi," told fortunes in various ways, including palmistry. As the age of witch hunts began to fade into the past, people began to think less of the actual features of the palm and their possible connection to the Devil and more of the art itself and its own connections to either magic or science.

Palm reading in the Renaissance

Palm reading remained popular throughout the Renaissance, although rulers weren't always fans. In 1530s England, palmistry wasn't officially popular – not by the standards of the government, anyway. One of Henry VIII's statutes, according to the Independent, called the art "a crafty means to deceive people." But by the 1650s, Europe was overrun by pseudo-sciences; books on palmistry began to pop up around this time. Thomas Hill was a jack of all the mystical trades, and wrote about both astrology and palmistry.

By that point, scholars had begun searching for scientific reasons behind the art. Science, magic, and religion have always had an uneasy coexistence throughout the world, and it was finally time for science to oust magic from its place when it came to palm reading, they decided. "Chirology" began to replace palm reading: though they were the same thing, a scientific name was an attempt to rationalize the art. At the same time, male scientists began to push female fortune tellers out of their own profession, to make it more interesting to the British upper class.

Palm reading during the 19th and 20th centuries

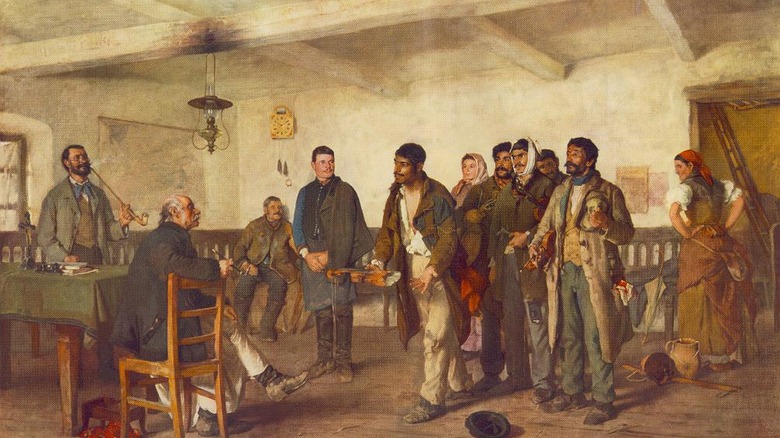

Palm reading was elevated in popularity during the 19th century due to the efforts of palmists William Benham, Casimir d'Arpentigny, and William John Warner (also known as Louis Hamon or Cheiro). Both d'Arpentigny and Benham became interested in palmistry after being introduced to it by the Roma people.

According to Hand Reading, Benham didn't really make palmistry into a proper science, even though that was his original goal. He focused on classifying the planets to fit with a handshape, which is now seen as unreliable and unscientific. He also proposed a system for figuring out what someone's career should be from their hand. Benham and d'Arpentigny both did work on the morphognomy of the hand, fingers, and thumb, which essentially meant studying the psychology of the hand. Benham specifically saw the lines of the palm as expressions of the flow of energy in the palm, and felt that the whole hand should be considered when making a judgement, instead of just the fingers. He used photographs and hand prints of prisoners in his work, and founded a school of palmistry in New York, as well as an Institute for Vocational Guidance.

Famous palmist William John Warner (or Louis Hamon, or Cheiro) wrote a book on palmistry at the age of just 13, and was known for having wealthy clients. When he died in 1936, Time reported that a nurse who was there said the clock outside his room struck the hour of 1am three times.

Julius Spier and Carl Jung

Julius Spier wrote the first work on palmistry that also took psychology into account: "The Hands of Children." Carl Jung wrote the introduction, where he focused on bringing palmistry and astrology up from their centuries of obscurity, feeling that they were useful and shouldn't be thrown away without due cause. He also felt that in the twentieth century, science had really only been progressing for about 200 years, and the superstition of the past was worth investigating. Hands, he wrote in his introduction, might well reveal some kind of truth (via "The Hands of Children").

Patti Lightflower, a professional palmist, agrees with Jung that Julius Spier's work focused on the intuitive side of palmistry. It takes time to build up that level of skill, however. On the other hand (pun totally intended), knowing both the physical feel of the hands and the meaning of each element found on them equals knowing everything at once. "A model of our psyche is hiding in the palms [of] our hands," writes Patti Lightflower on I Read Hands.

Modern palm readers

People who read palms today often combine it with psychology and holistic healing. Other methods of divination are also often used, depending on the practitioner.

Professional palmist Patti Lightflower has researched and investigated the modern science of palmistry over the past 30 years. She considers palmistry to be the understanding of the body's language, and teaches classes in palm reading. According to her site I Read Hands, people's biology and self are connected. Their hands interact with the world and the world, in turn, interacts with their hands. For example, someone can explore their surroundings or be visibly afraid of where they are. The fingertips contain plenty of nerve endings; what are their brains telling them to do, by sending messages through their nerves?

She claims that human beings also work at different electrical speeds, which can be seen through the different patterns on people's palms and fingers by way of nerves working beneath the surface. Experiences combine with behaviors and personality to equal a person, and the hands are part of that, forever sensing what's going to happen next (via I Read Hands).

World religions and palm reading

Islam forbids divination. According to Islamic Studies, the outlawing of divination falls into several categories. Muslims are not allowed to take part in games of chance other than those made by way of a decision (for example, drawing straws to decide something between multiple people). Muslims are also not allowed to seek knowledge about themselves through superstitious means or by way of another god or goddess. Superstitious divination of course includes palmistry, astrology, geomancy, and various other fortune telling methods.

The Bible also forbids practicing palmistry, even though it appears throughout ancient Judaic texts. It is mentioned first in a chapter of Merkabah mysticism. The chapter references obscure symbols in palmistry, and doesn't have a relation to astrology, as is common elsewhere, writes Jewish Virtual Library. It does make clear that the mystics figured out whether a man was ready for specific teachings by using palmistry.

Several Jewish books were also written to summarize palm reading at the start of the 16th century, though the traditions of the early kabbalists (of the 12th century) were rarely mentioned. The kabbalists examined the hands for good things at the end of the Sabbath.

The Romani trifecta of fortune telling

Tarot cards, crystals, and palm reading are the trifecta of fortune telling, particularly among the Romani people. Tarot, like palm reading, tells stories about people's lives, including where they're going and where they've been.

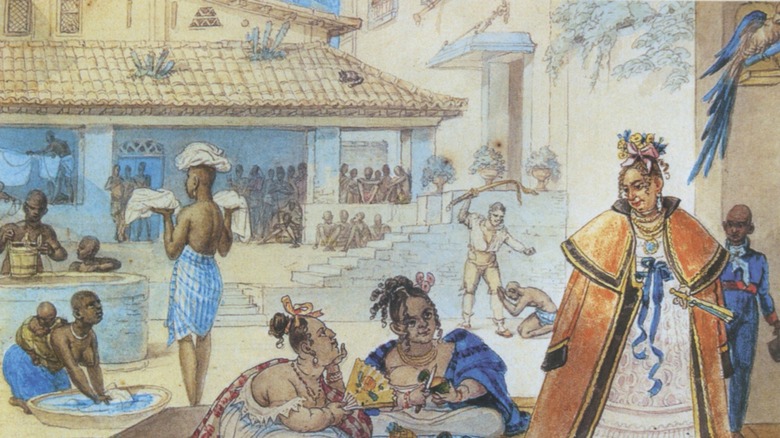

According to the Human Rights Fund Progress, fortune telling was a Romani female livelihood and it was only done with non-Romani. The Romani stylized their fortune telling to either be lofty, familiar, or homely, depending on the client. Though divination was valued by those who paid for the service, the practice was historically punished harshly by the Catholic Church. Whoever told fortunes could even be arrested without a warrant.

Playing cards were eventually also used to tell fortunes; it is unclear whether it was originally intended that they were used for telling fortunes or playing games. In the 16th century playing cards were used for fortunes, but by the 18th they were being used for their current more common purpose in daily life.

Palm reading in media

Caravaggio's 1595 painting "The Fortune Teller" (pictured) features a palmist – a female Romani "drabadi" – who steals a young man's ring while doing her job (via Google Arts and Culture). This detail was likely included to indicate just how untrustworthy the Romani were seen at the time. "The Gypsy Crown" children's series, by Kate Forsyth, is set in the 17th century and features times being hard for the Romani because of the aura of fear that these types of paintings created.

The paintings featured in the Human Rights Fund Progress are split into more modern paintings and older pieces. In 1993's "Fortune Teller" and 1998's "Line of Destiny" the focus is on the Romani fortune tellers performing the art. In 1625's "The Scene of Fortune Telling" and 1710's "Fortune-teller," by contrast, the eye is drawn to the Europeans having their fortune told, while the Romani are shadowed by scarves or shadows. The dark shadowing possibly was also meant to indicate untrustworthiness.

Author Diana Gabaldon, meanwhile, uses palmistry to foreshadow events in her "Outlander" series (via Google Books) when the protagonist, Claire, has her palm read. One aspect the palmist sees is that her marriage line splits, indicating bigamy, which (spoiler) does indeed come to pass.

Modern dermatoglyphics

Dermatoglyphics is the study of ridge patterns in skin, specifically of the palms and fingertips. It is often used in criminology in regards to fingerprinting, and often vital in making formal identifications and linking a suspect to a crime scene (via Brown and Rutty's 2005 article in the Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine).

Everyone's ridge patterns are completely unique, writes Indiana Public Media. They were created in the womb, forming as the result of stress patterns. During fetal development, if the growth of the limbs is changed in any way, subsequent changes in the ridges of the skin are common. Possibilities are chromosomal aberrations or gene mutations, writes Health Jade. Papillary ridges (on the palms and soles of the feet) form early and are unchangeable during the later stages of pregnancy. They only get bigger during someone's life, but otherwise don't change.

Certain diseases leave their tell-tale signs on the palms and the ridges of the fingertips. Scientists have catalogued various genetic diseases with unusual palm prints. For example, schizophrenia, certain allergies, and fetal alcohol syndrome have all left specific fingerprint patterns. Dermatoglyphics have therefore been used in genetics, anthropology, and medicine to identify diseases, since it is quick, cheap, and a good diagnostic tool.