The Insane True Story Of L'Oreal's Founder

Beauty standards might change as the centuries go by, but one thing stays the same: People always want to look their best. Fortunately, in our 21st-century world, making ourselves look attractive isn't nearly as deadly as it once was. Gone are the days of using arsenic and belladonna to change our appearance for the better, and that's in large part thanks to Eugene Schueller and L'Oreal.

Schueller founded L'Oreal in 1909, and it was built on the idea of making safe hair dyes. It was such a big deal that today, L'Oreal has become one of the giants of the fashion industry. Forbes says that as of 2021, they're worth around $225.7 billion, bringing in $31.9 billion in annual sales. According to Business Insider, heiress Francoise Bettencourt Meyers spent years being the richest woman in the world, with her one-third-of-the-company inheritance being worth around $58.6 billion.

The story of L'Oreal's founder, though ... that's the stuff of the shadier side of history. Schueller's quest to find a hair dye that was safe to use regularly might sound harmless enough, but alongside striving to give people the means to feel more beautiful, there's an ugly side, too. It's one that involves Nazis, the persecution of Europe's Jews, assassinations, bombings, and growing that fortune with the help of the Third Reich. It's dark stuff, indeed.

The official story from L'Oreal on their founder

Let's get the low-down on L'Oreal founder Eugene Schueller from L'Oreal themselves. They say, "Eugene Schueller seized the moment. He creates the beauty that moves the world," and that's definitely accurate.

The son of Parisian pastry shop owners, Schueller was a brilliant chemist who, in 1907, launched his first product line. The original company was called the Societe Francaise de Teintures Inoffensives pour Cheveux — or, the French Company of Inoffensive Hair Dyes — and that's exactly what they sold. It was pretty genius, and for the first time, women could dye their hair without worrying about the chemicals they were putting on their scalp.

He did pretty well, and when production was interrupted by World War I, L'Oreal says that he enlisted and was recognized for his valor in combat. After the war, two important things happened, and they'll be important later: L'Oreal mentions that he acquired a company called Valentine, and in 1934, they started manufacturing the first sunscreen. L'Oreal goes on to laud his creativity, business sense, and ability to look ahead at developing trends to see just what was going to be a massive hit with consumers, and that's certainly true. But there's a lot that's left out of this history — for example, they just sort of skip right from 1933 to 1953, and history buffs might get a little suspicious about that ... as they should.

He had an ... interesting take on company policies

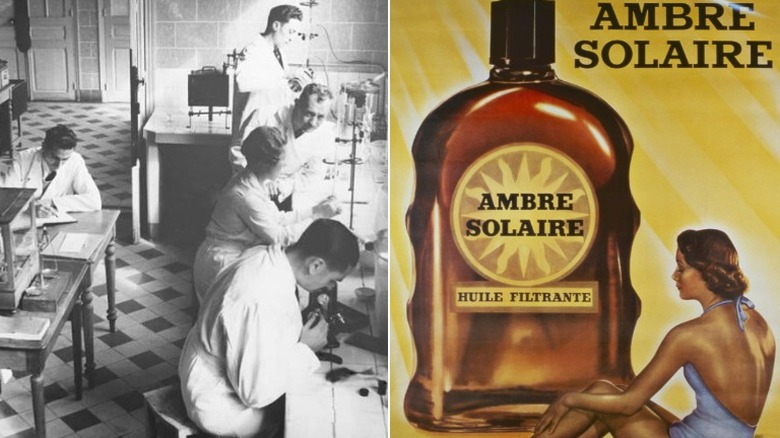

L'Oreal launched the first sunscreen in 1935. It was called Ambre Solaire, and according to the United Kingdom's Science Museum, it was created not by Eugene Schueller personally, but by L'Oreal chemists who designed it to help people tan without burning. This was about the same time that regular vacations for workers were introduced: People wanted to take advantage of their time off, and that meant going to the beach. It made Schueller both rich and widely known, but ironically, when it came to his own employees, he hated the very idea of a vacation.

According to the Smithsonian, Schueller widely condemned the policies implemented by left-wing Prime Minister Leon Blum. These were things like a five-day work week and regular raises — along with two weeks of vacation time. They all ran in opposition to the ideas that Schueller had been developing throughout the decade. For example, he was a huge proponent of "proportional salary," which basically meant you got paid for the work you did, not how much time you were there.

While L'Oreal quotes Schueller as saying, "a company is not walls and machines, it's people, people, people," The New York Times says that it's a bit more complicated. In 1941, he gave a speech in Paris and noted (in part): "I consider it impossible to build a representative state based on universal liberty and equality ... Everyone must realize that many are his superiors and deserve more than he."

Eugene Schueller's bank-rolling of a far-right extremist group

In the 1930s, France was home to a far-right extremist group called the Comite Secret d'Action Revolutionnaire, and according to research from Old Dominion University, they were — in a nutshell — an ultra-violent paramilitary organization that was prepping to overthrow the French government and install a military dictatorship, ahead of re-establishing the monarchy. By 1938, they were already connected to a series of assassinations, including that of several Italian, anti-facist exiles.

They were more commonly called the Cagoule because of their tendency to hide their identities beneath hoods, and they were hardcore. French police connected them to several bombings, a gun-running network between France and Italy, a series of underground prisons, and the training of terrorist cells. It was put together in response to the development of Prime Minister Leon Blum's leftist government, and one of their major bankrollers was none other than Eugene Schueller.

According to The Jerusalem Post, Schueller not only bankrolled the group, but ended up becoming good friends with leader Eugene Deloncle (pictured) (via the Smithsonian). L'Oreal headquarters was one of their regular meeting places, as they hatched plans to assassinate Blum. Later, La Cagoule would throw in on the side of the Nazis, and L'Oreal remained pretty tight with them. Several high-ranking members of La Cagoule ended up working in the equally high ranks of L'Oreal, and one married Schueller's daughter.

He was incredibly vocal about his views

When France fell to the advancing Nazi forces, they fell very, very quickly. According to the BBC, it took just six weeks: German air raids started on May 10, 1940, Paris was occupied on June 14, and France officially surrendered on June 22 (pictured).

Eugene Schueller took it both as an offense and proof that what he'd been saying was right: Democracy, he said, only led to weak individuals being put in charge of a weak nation. Instead, he envisioned a world where the everyman would bow to what he called (via The New York Times) the "Fuhrers of the professions."

He was definitely not quiet about his views, either. According to the Smithsonian, he gave regular speeches and lectures, and wrote a lot — including a 1941 book called "La revolution de l'economie." Included in that work were copies of some of Adolf Hitler's speeches, and Schueller's support of his ideas. He wrote, "We don't have the gift that the Germans had ... We don't have the faith of national-socialism. We don't have the dynamism of a Hitler pushing the world." Schueller was one of the voices speaking to his fellow Frenchmen over German-controlled radio, and after the fall of France to the Nazi war machine, he promoted the idea that of course this revolution was going to be bloody — they always were. He wrote, "We must rip from men's hearts the childish concepts of liberty, equality, and even fraternity. [They only] lead to disaster."

Eugene Schueller was first in line to support France's new, Nazi-backed party

Historian Bertram M. Gordon says (via "The Condottieri of the Collaboration: Mouvement Social Revolutionnaire") that La Cagoule — with their secrecy, their hoods, and their masonic-esque initiation rituals (pictured) — had pretty much come to an end after 1937. After the fall of France, they reorganized into a public political party.

The Mouvement Social Revolutionnaire (MSR) was founded a few months after Nazi victory in France, and at the head was the same guy who had been at the head of La Cagoule, Eugene Deloncle. He was joined by former La Cagoule associates who had been exiled or jailed, returning only with the emergence of Nazi rule, particularly in Vichy (via "MSR: the National People's Legion"). Their mission statement included backing "severe racial laws to prevent such Jews ... from polluting the French race," and their slogan included "for an authoritarian, anti-democratic and anti-Semitic power."

According to The New York Times, the very first person to sign his name on the charter for this new political party was L'Oreal's Eugene Schueller. Their stance was so extreme that Henri-Philippe Petain — the French general who, says History, was named head of the Vichy State and later condemned as a Nazi collaborator — tried to talk Schueller out of throwing in with Deloncle and the MSR. Schuller declined the advice, funding the young party and donating space for their meetings. He also supplied them with transportation and equipment from L'Oreal when they needed to flee ahead of Allied liberation.

A middleman supplying the Nazis with paint

Eugene Schueller bought the company Valentine in the late 1920s. L'Oreal called it one more step on the journey of building a global empire, but according to the Smithsonian, there's a little more to the story.

Valentine might not be as widely known as L'Oreal is today, but they manufactured a product that was kind of adjacent to the beauty industry giant: They made varnish and paint, and during World War II, Schueller made sure they were making it for his side. It was a huge deal: Every military vehicle that rolled off the assembly lines needed to be painted, after all. In 1941, Valentine became one of the "first category" companies that supplied the German Navy with paint. The deal lasted for three years, and it was negotiated by Schueller, as then-director of Valentine. He partnered with a German company called Druckfarben via a German businessman named Gerhart Schmilinsky.

Schmilinsky, it turns out, wasn't just an ordinary sort of businessman: He was a key player in the Nazi's economic plan to strip Jewish citizens of their businesses and transfer those — and their assets — into Nazi hands. He had nothing but good things to say about Schueller, calling him "an ardent partisan of the Franco-German accord."

Eugene Schueller, his SS friend, and his political aspirations

Eugene Schueller didn't just go through World War II making shady business deals, and the Smithsonian says he was also pretty buddy-buddy with German SS intelligence officer Helmut Knochen (pictured). Knochen was a high flyer in the SS, and after signing up to become a member of the Nazi party in 1932, just eight years later he'd risen through the ranks to become a senior commander of their security police. By 1942, he was overseeing the entirety of occupied France and Belgium, and according to the Jewish Virtual Library, chief among his tasks was deporting France's Jews to Nazi concentration camps, and executing anyone who was causing trouble.

His crimes were on a level that eventually got him a death sentence (which was never carried out — he was ultimately pardoned and retired in Germany), so he was a big deal. Schueller was apparently convinced that Knochen could help him get into politics — he had his eye on a position in the Vichy government: the minister of the national economy.

Schueller didn't exactly get there, but Knochen found him such a big help that he did shortlist him for a different ministerial position that never quite came to fruition. Later, when Knochen was sitting on death row, Allied investigators were given a list of 45 of his best agents. Schueller was on it, called one of his "voluntary collaborators."

Eugene Schueller & Andre Betttencourt

In 2010, France 24 was reporting on questions of whether or not Andre Bettencourt — the husband of Eugene Schueller's daughter Liliane — had made massive donations to the presidential campaign of Nicolas Sarkozy. What was going on there was still being investigated, but the news outlet pointed out that this wasn't the first time some serious questions had been raised about Bettencourt (pictured).

Bettencourt was one of Schueller's inner circle from way back, going all the way to La Cagoule. At the time, he was just as outspoken as Schueller was, once writing for the Nazi-sponsored "La Terre Francaise" that Jews were "hypocritical Pharisees," and that their "race has been forever sullied by the blood of the righteous. They will be cursed."

And here's where things get a little weird. Bettencourt seemed to switch sides around 1943, suddenly joining the French Resistance with a different friend, who would become President Francois Mitterrand. He spoke more widely about that, calling his dabbling in extremism and support of Nazi beliefs "youthful mistakes." Then, it gets a little stranger. In spite of the fact that Bettencourt often tried to brush aside his work alongside the Nazis early in the war for his participation in the Resistance later, that's not all he was doing. When things caught up to his old pal Schueller, he was right there to lend all the help he needed.

He was ultimately acquitted of any wrongdoing

The Allied armies started retaking France in 1944, and for collaborators, justice was oftentimes very, very swift and sometimes extremely bloody. Some went to trial, some were just executed, and according to the Smithsonian, Eugene Schueller escaped detection for a while, but was officially sanctioned on November 6, 1946.

The charges of both political and economic collaboration were so serious that had he been found guilty, Schueller would have faced the loss of his company and — perhaps — even the death penalty. But in a decision that's both shocking and not-at-all shocking, all charges were ultimately dropped.

Schueller was cleared of economic collaboration in large part because of the massively complicated and deceptive layers and layers between himself, L'Oreal, and the deals he'd made with German companies like Druckfarben. When it came to clearing himself of political collaboration, that was just as complicated. He started off by claiming that he'd never actually been a member of La Cagoule, and anything anyone might have heard to the contrary was just propaganda. Then, he called in some witnesses, like Andre Bettencourt. Leaning heavily on the fact that he'd been in the Resistance, Bettencourt then used that clout to lend some credence to his testimony that Schueller had actually been sheltering Jews and funding the resistance, not helping the other side.

It was all convincing enough that Schueller walked free, and later, witnesses — including Bettencourt — ended up with high-ranking positions within L'Oreal.

Here's how much money Eugene Schueller made

The war years were bloody, horrible, and incredibly hard, and it came with struggles from the front lines to the homefront. Rationing was a huge deal with tons of supplies redirected to the war effort. People needed to get creative, and oftentimes, they needed to do without.

Take makeup and other cosmetics. Culture Trip says that while Nazi directives instructed women to stop using makeup and go natural, the Allies encouraged their women to use a ton of it. It was good for morale, the theory went, but in occupied territories and front-line countries, it wasn't always possible. Take France: Cosmetics were so scarce that women reformed tubes of lipstick from melted pieces.

Meanwhile, the Smithsonian says that Eugene Schueller and L'Oreal made a fortune during the war years. While Schueller's personal wealth increased by around 10 times, L'Oreal's sales numbers quadrupled between France and Great Britain's late-1939 declaration of war (via History) and the Allied liberation in 1944.

How the heck did that happen? At the same time L'Oreal's sales to Germany were low, the spiders' web of companies that had been set up to sell paint — a military necessity — to the Nazis also allowed for the flow of raw materials to go the other way — into L'Oreal. And since cosmetics were ultimately deemed to be of "no direct military interest," that was A-OK.

L'Oreal's German headquarters and the lawsuits

L'Oreal has been on the receiving end of lawsuits and investigations into the wartime conduct of their founder and other high-ranking officials. In 1995, for example, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that Andre Bettencourt was under investigation for his pro-Nazi writings, and they were also looking at his claims of working for the Resistance — an association that French Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld said only began about 10 days before the Allies liberated Paris.

L'Oreal's German headquarters is also the site of a massive lawsuit and a struggle that's been going on for decades. According to a 2004 piece in The Guardian, it started in 1937 when the Rosenfelder family fled ahead of Nazi persecution. They were forced to sell their land for just 12% of the estimated value, and not only does Edith Rosenfelder — the only surviving family member — say they were never given the money, she also adds that her family was still sent to the camps: Her mother died in Auschwitz, and her father passed away three years later in a Red Cross facility. L'Oreal then bought the property from the German insurance company who'd gotten it from the Rosenfelders.

Although post-war legislation says that deals like this one can be declared unlawful and property had to be returned, Forbes reported in 2005 that Rosenfelder's previous cases had been dismissed, with L'Oreal saying they can't be held responsible for what happened in the past.