What Really Happened To The Shroud Of Turin?

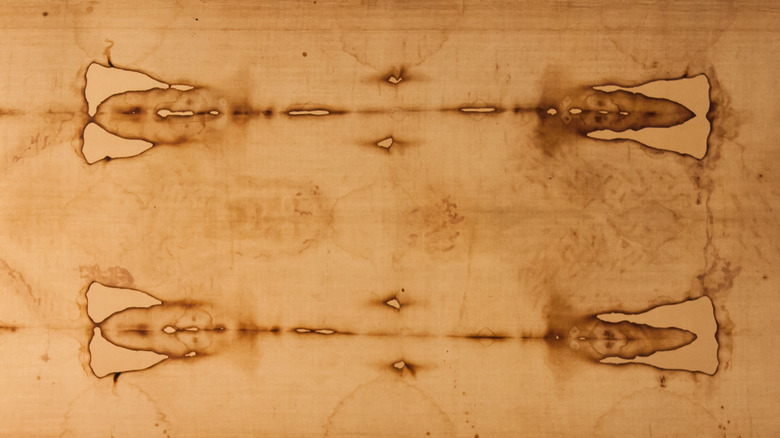

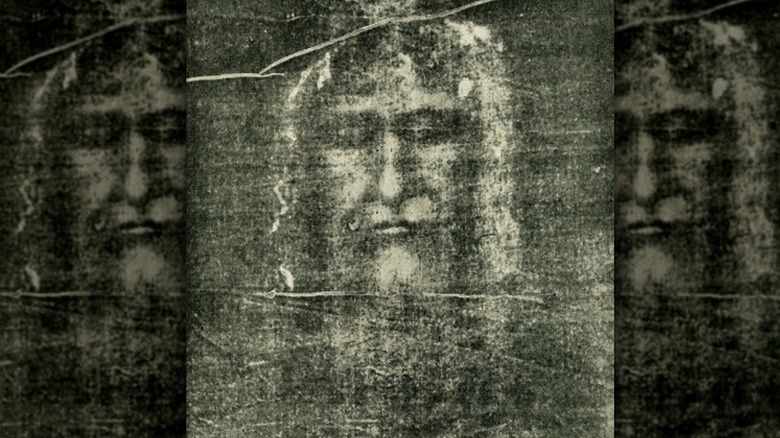

In the mid-1350s, French Knight Geoffroi de Charny presented the dean of the church of Lirey, France, with a roughly 14x3.5-foot linen cloth, per Britannica. According to legend, Charny claimed the cloth — which is imprinted with the faint image of a man — was the burial shroud that was laid on the body of Jesus of Nazareth following his crucifixion. As reported by History, no historical records prove the existence of the shroud prior to the mid-1350s, which religious texts suggest was more than 1300 years after Jesus of Nazareth was crucified and subsequently entombed.

Immediately upon receipt of the purported relic, the shroud was put on display at the church of Lirey. As news of the display spread, pilgrims traveled great distances for a glimpse of the shroud, and the church received a number of sizable donations. Although many believed Charny's claims about the origin and authenticity of the shroud, church leaders were skeptical. History reports then-bishop of Troyes, France — Pierre d'Arcis — was convinced it was a fake. In a letter to Pope Clement VII, d'Arcis accused the dean of the church of Lirey of dishonestly presenting the shroud as an authentic relic in an attempt to make money. Pope Clement VII ultimately determined that the church of Lirey could continue displaying the shroud. However, they were ordered to display it as a manufactured religious "icon" as opposed to a historic "relic."

The shroud's journey from Lirey to Turin

The shroud remained in the possession of the church of Lirey until 1418. Amid the Hundred Years' War, Geoffroi de Charny's granddaughter, Margaret de Charny, expressed concern that the church could be overrun and the shroud either damaged or stolen. As reported by History, she and her husband offered to keep the shroud in their castle, where it would be safe from harm.

Although Margaret and her husband vowed to return the shroud to the church of Lirey when the danger passed, they refused to honor the agreement. Instead, they kept the shroud and toured Europe, claiming it was Jesus of Nazareth's authentic burial cloth. Margaret ultimately sold the shroud to the royal house of Savoy, which would eventually ascend to the Italian throne. Although she received two castles in exchange for the shroud, she was excommunicated for selling a religious icon. The house of Savoy initially displayed the shroud in the Chambéry's Sainte-Chapelle. However, In 1578, it was moved to Turin's Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, where it remains to this day. Based on its location, the icon became known as the Shroud of Turin.

Even though Pope Clement VII declared the Shroud of Turin was not Jesus of Nazareth's authentic burial cloth, it remains "one of the most sacred religious icons on Earth," National Geographic reports. The Shroud of Turin also remains a subject of heated debate.

Scientific testing only raised more questions

While Christians believe the Shroud of Turin is the actual cloth that covered Jesus of Nazareth's body when he was entombed, others argue that it was created as a work of art. As reported by National Geographic, the Shroud of Turin has undergone extensive testing by botanists, chemists, forensic pathologists, microbiologists, and physicists. However, their results were often conflicting. Although a vast majority of scientists believe the Shroud of Turin is a work of art, they can not prove how it was made.

In 1981, a group of scientists with the Shroud of Turin Research Project determined, "The Shroud image is that of a real human form of a ... crucified man." They also concluded "the blood stains are composed of hemoglobin" and said no artificial pigments were found on the shroud. In 1988, researchers sent samples of the shroud to the Universities of Arizona, the University of Oxford, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology for carbon-14 testing with the Vatican's authorization. National Geographic reports all three concluded with a 95 percent degree of reliability that the Shroud of Turin originated between 1260 and 1390.

In an interview with National Geographic, physicist Paolo Di Lazzaro admitted, "It is unlikely science will ever provide a full solution to the many riddles posed by the shroud. ... A leap of faith over questions without clear answers is necessary — either the 'faith' of skeptics, or the faith of believers."

The shroud has been in Turin for more than 440 years

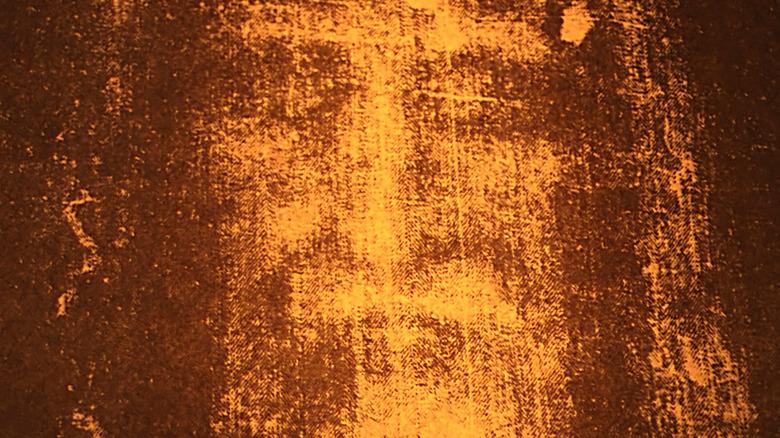

As reported by National Geographic, the hue of the image has been tremendously difficult to identify or replicate. It is also unknown how the image was produced, as it barely penetrated the fabric. At this time, "every scientific attempt to replicate [the Shroud of Turin] in a lab has failed." Still, Paolo Di Lazzaro admitted that the image might have been created using some kind of ultraviolet light. However, the power needed to produce a similar image would exceed any available modern sources. Indeed, those who believe the Shroud of Turin was Jesus Christ's authentic burial cloth believe the radiation theory could prove the image was produced by "divine light."

Although the shroud is rarely on display, CNN reports that an estimated 200,000 people visit the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist — where it's housed — each year. On Easter 2020, images of the Shroud of Turin were live-streamed amid lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic.