The Untold Truth Of The Bible's Saul

One of the best known figures from the Bible is David, the shepherd boy who slew a giant and became king. But lurking in the background of that popular Sunday School tale is the glowering King Saul, who both admires David and violently envies his successes. Saul, as the first king of Israel following centuries of lawlessness among the Hebrew people, is an interesting character in his own right. Chosen by a desperate people in a time of great danger, Saul constantly tried and failed to live up to the standards set for him by both God and his own people.

He is also a prime example of the way that political bias can creep into the Bible, with a recurrent tension running through the biblical narrative between accounts that are pro-Saul and those that are anti-Saul. If all you know about Saul is that he was a king who hated David, there's a lot more to know about Israel's first king.

Israel's first king

If you know one fact about King Saul, it's likely that he was the first king of the United Monarchy of Israel and Judah. You might expect that Israel's first king would have come at the beginning of the existence of Israel, but as the Jewish Virtual Library explains, the twelve tribes of Israel had occupied those lands for hundreds of years before instituting a king. According to the biblical account, the Israelites claimed the Promised Land of Canaan for themselves after escaping slavery in Egypt and doing a genocide on basically all of the Canaanites. Following that time, the twelve tribes lived as a loose tribal confederation with no formal leadership. In times of crisis, God would appoint military and/or religious leaders known as judges to deliver the Israelites from trouble (this is, as you may guess, what the Book of Judges is about).

The repeated refrain from the Bible during this era of Israelite history is that in those days there was no king in Israel and every man did what he wanted. However, this loosey-goosey way of life was an issue when it came to the superior military might of the Israelites' neighbors, the Philistines. The Hebrews began asking for a king to lead them, against God's wishes. Ultimately Saul was chosen for the right reasons: he was the tallest and handsomest of all the Hebrews.

Two views of King Saul

The story of Saul and his kingship are told in the biblical Book of Samuel (divided into two books in Christian Bibles). Although the traditional view of this book is that it was written by the prophet Samuel himself (with other prophets supplementing the parts that take place after Samuel's death), biblical scholars believe that like much of the rest of the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Samuel is actually compiled from multiple, often conflicting, documents without much effort from the compiler to reconcile them. As a result, as the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, events are often repeated in contradictory ways. And one of the things that becomes clear is that one layer of the text is very anti-Saul (and arguably anti-monarchy as a whole), and one is more generally pro-Saul.

These conflicting views on Saul would continue long past the biblical era and into modern times. The Jewish Encyclopedia asserts that one group of rabbis felt that Saul's punishment at God's hands is a sign of his weak moral character whose only virtue was being tall and handsome. Another group, however, argues that as God's anointed king, Saul was both morally upright and perfectly just. Either view is biblically justified due to the way one chapter will say how great Saul is and the next will make him look like an unstable fool due to the conflicting layers of text in the book.

Becoming king three times

Thanks to the pastiche-like nature of the Book of Samuel, the Bible actually contains not one, but three versions of the accession of Saul to the throne of Israel. According to My Jewish Learning, the Hebrew people demanded from God a king in the face of the military expansion of the Philistines, despite God's reservations about a human ruler. Chapter 9 of 1 Samuel says that Saul was chosen king when he went out looking for his father's donkeys that had run off and stumbled across the prophet Samuel, who unexpectedly anointed him king. The very next chapter, however, recounts a different version of Saul's selection as king, where Samuel summons the tribes and clans of the Israelites in order to choose a king and finds Saul hiding among the baggage when he is casting lots to find the man God has chosen as king.

The third account comes in the next chapter in the account that My Jewish Learning calls the most reliable of the three. In this version, Saul leads a military expedition against the Ammonites, who have laid siege to the Israelite town of Jabesh-Gilead. Saul, emboldened by the spirit of God, routs the Ammonites and delivers the people of Jabesh. After this decisive military victory, the people, together with Samuel, unanimously proclaim their allegiance to Saul as their king. In all three versions, Samuel anoints Saul king.

Saul among the prophets

In 1 Samuel 10:11, there is a story told in which Saul, after having been anointed by Samuel (the first time), has his heart changed by God and he sings and dances and starts prophesying. The people around him are confused and say, "Is Saul also among the prophets?" This story is meant to give an origin for what was apparently a common saying at the time of the composition of the Book of Samuel. But as with most things about Saul, a second origin is given as well. In chapter 19, after Saul tries and fails to kill David, he is once more seized by the spirit of God and begins prophesying, causing people to once again ask that question we all know and love, "Is Saul also among the prophets?"

The problem is, we have no idea what this saying means for sure. Rabbi Michael Howald gives the most likely explanation, that it refers to situations in which even the most unexpected person participates in a given event, like a Marvel movie hater who gets really into the Eternals or whatever. Such a saying would rely on a popular understanding of Saul as a hater of the prophets. This view is incredibly likely, since–as the Jewish Virtual Library explains–the prophets of Judaism served largely as a counter to the despotism of certain Hebrew monarchs.

Rejected as king, twice

As My Jewish Learning explains, Saul enjoyed military successes against the Philistines despite their superior might by leading a guerrilla war against their enemies, full of surprise attacks and ambushes carried out by only a few hundred men. However, despite the fact that he likely drove the Philistines out of central Israel, Saul lost favor with God and was rejected by him as king. As with most major events in Saul's life, this happens twice. The first account occurs in 1 Samuel 13, when Saul and his troops are waiting for Samuel to arrive to perform a burnt offering prior to a battle. When after seven days Samuel does not arrive at the appointed time, Saul decides to perform the sacrifices himself. Just as he finishes, Samuel arrives and condemns him for his lack of faith, telling him that God has chosen a new king.

The second account of Saul's rejection comes in chapter 15, where God instructs Saul to not only defeat the Amalekites, but to utterly wipe them out, killing man, woman, child, and all their animals. After Saul defeats the Amalekites, he deems it strategically prudent to take their king hostage and keep the best of their cattle for himself. At this point, God regrets ever having made Saul king and decides to pick a king who will do a genocide when he asks him to.

Saul's trouble with David

If you know two things about King Saul, the second thing is probably his stormy relationship with his God-chosen successor, David. As the Jewish Encyclopedia points out, Saul of course meets David two times: first when David is chosen to come play the harp to help even out Saul's depressive moods, and the second time when the small shepherd boy unexpectedly kills the Philistine giant Goliath. The Jewish Encyclopedia goes on to explain that even though Saul rewards David by giving him his daughter Michal in marriage and Saul's son Jonathan becomes David's best friend (maybe more than friends?), Saul becomes increasingly jealous of David's popularity and military successes. As My Jewish Learning points out, Saul becomes paranoid that his new son-in-law is conspiring to take the throne from him. Consequently, Saul tries to kill David multiple times.

In 1 Samuel 10, Saul first tries to kill David by straight up pinning him to the wall with his spear, but David dodges twice. He then tells David that he can't marry Michal until he brings Saul 100 Philistine foreskins, thinking that David will definitely die in this attempt. Instead, David brings back twice as many. Jonathan helps David escape Saul's wrath, but Saul and his army pursue him, even as he escapes into Philistine territory, with Saul executing as traitors a group of priests who gave David aid.

David almost killed a pooping Saul

As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, after fleeing from Saul, David finds himself the leader of a band of about 400 men, whom 1 Samuel describes as "desperate, in debt, or discontented." David and his group of men then spend some time working as freebooters–essentially like Robin Hood and his Merry Men going around saving Israelite towns from Philistines while dodging King Saul's armies. At this point, Saul regards David as a full-on rebel and focuses as much attention on him as on the Philistines. This leads to an incident in 1 Samuel 24 in which Saul chases David to his hiding spot and then goes into a cave to poop, not knowing that this exact cave is where David is hiding. David sees the king doing his business and realizes he could kill him. Instead, he cuts off the corner of his robe to later reveal to him the mercy he had shown him.

Naturally, this happens a second time, but without the pooping (obviously from the camp who respected Saul more). In 1 Samuel 26, David sneaks into Saul's camp and breaks into his tent while he's sleeping. Again, he spares the king's life but steals his spear and water jug to show the king how close he had come to death. At this point, Saul realizes he has been wrong to pursue David and blesses Israel's future king.

Hiring a necromancer

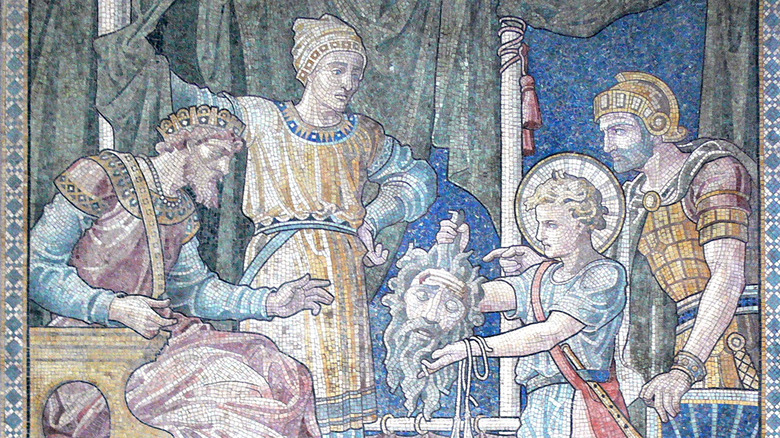

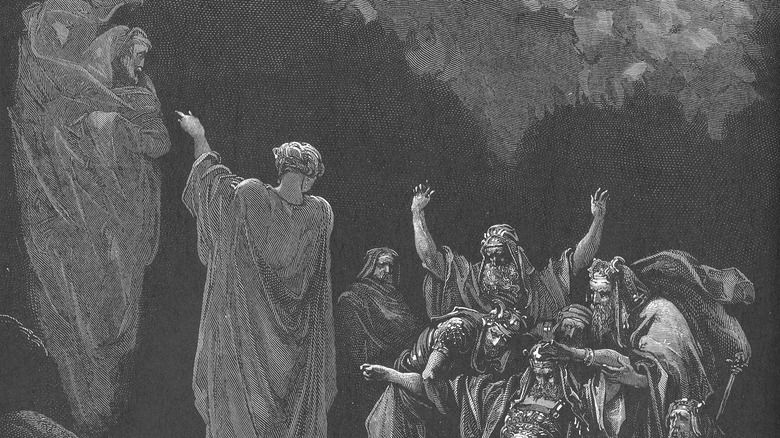

One of the strangest passages in the Bible comes in chapter 28 of the Book of Samuel. After giving up his pursuit of David, Saul finds himself dealing with renewed aggression from the Philistines. As Encyclopedia.com explains, it had previously been customary for Saul to consult the will of God prior to battle, primarily through the interpretation of dreams, casting lots, or consulting a mysterious divination device utilized by the high priest known as the Urim and Thummim. However, due to his having been rejected by God, Saul finds himself cut off from knowing God's will. Desperate for advice on how to proceed in battle against his enemies, Saul consults a woman who has come to be known as the Witch of Endor. This woman was a practitioner of a foreign religion that had been outlawed by Saul himself, but desperate times, etc.

Saul, disguising his identity, demands that the woman use her necromantic abilities to summon for him the ghost of Samuel (side note: Samuel died a little while before this) that the prophet might advise him one more time. Instead, ghost Samuel curses him for a fool and lets him know that God no longer hears Saul's prayers. God's favor has fully shifted to David and Saul will lose not only the next day's battle, but also his kingdom and his very life.

The two deaths of King Saul

As with basically everything else in the life of Saul, there are two different accounts of his death. The more sympathetic version in 1 Samuel 31 says that after being routed by the Philistines, Saul's sons were killed and Saul himself fell on his own sword in desperation, dying together with his sons and armor-bearer. The more critical version in 2 Samuel 1 says that Saul was too cowardly to kill himself and so roped a passing stranger into doing it for him. Either way, the Philistines took the bodies of Saul and his sons and mounted their heads on the wall as a display of power. Much later, David is able to rescue their bones and bury them on family land.

As My Jewish Learning explains, it's hard to know many concrete details about Saul's reign. The traditional Hebrew text of the Bible used by Jews and many Christians states that Saul reigned only for two years and also that he became king when he was one year old. Modern translators and commentators consider both of these facts extremely improbable and most translations modify this verse to say that Saul became king at age 30 and ruled for either 22, 32, or 42 years. The Jewish Encyclopedia judges that Saul's reign as a whole was a failure, apart from his success in uniting the tribes of Israel and giving a prominent position to David.

Succession crisis in Israel

Following the death of Saul and three of his sons at the hands of the Philistines, David was still not the uncontested king of Israel and Judah, despite having been named so by God himself. In fact, there was something of a succession crisis between David and one of Saul's surviving sons, Ish-bosheth. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, Saul's general Abner names Ish-bosheth as king in the north, in a small kingdom still under Israelite control east of the Jordan River. In the south, however, the Israelite forces crown David the king of the southern tribes of Judah. There is a civil war between the two kings, including a strange battle in 2 Samuel 2 in which 12 soldiers on each side all kill each other, but this status quo doesn't last long. After only two years as king, Ish-bosheth is assassinated by two of his own generals, who hoped they would be rewarded by David (they weren't; he executed them for treason).

But even in death Saul continued to haunt David. A story in 2 Samuel 21 tells how during David's reign as king, a three-year famine cripples the people of Israel. Upon consulting the Lord, David finds out the famine is punishment for Saul's unjust treatment of a tribe called the Gibeonites. There is no relief for the Israelites until David hands over seven of Saul's descendants to be hanged by the Gibeonites.

Was Saul bipolar?

Much has been made in modern times by commentators about King Saul's mental health. The fact that he alternated from dark moods that had to be calmed by David's harp playing to such surprising moments of ecstatic joy that a common saying arose from it has certainly given some people pause. The fact that he ended his life by suicide only adds fuel to the fire for some people. Dr. Michael Eleff lays out some of the attempts by modern doctors and commentators to retroactively diagnose King Saul, which include looks at his seeming bipolar depression, his paranoia, impulsivity, sudden uncontrolled rages, and recurrent despair.

Hebrew professor Joel Baden, however, urges caution when it comes to trying to diagnose someone who is said to have lived some 3,000 years ago. Furthermore, he wonders whether the "evil spirit" that the Bible says was the cause of Saul's dark moods should even be equated with mental illness. The danger of such an assessment, he says, is in equating mental illness with the moral lapse Saul shows in his repeated attempted murders of David. Additionally, identifying an evil spirit sent by the Lord with mental illness assigns an agency, cause, and motive behind mental illness, which is not only the wrong way to think about illness, but also potentially dangerous. The idea of Saul's actions as only explainable by madness shows the clear pro-David bias of the author of Samuel.

Did Saul even exist?

Another issue with trying to assign modern categories of mental illness to a biblical figure like King Saul is the fact that King Saul might not have even existed. As My Jewish Learning explains, the archeological record of Saul's kingship is practically non-existent. The available information seems to suggest that at this time, Israel was still largely an agricultural society with very little central government or organization. At the time of Saul, a fortified area northeast of Jerusalem called Khubert ed-Dawwara had about 100 inhabitants, which would have been a bustling metropolis at that time. Saul is never described as having established a capital or palace; he is only ever said to have set up a tent under a tree. By contrast, there is a wealth of archeological information about the Philistines of the 11th century BCE, who enjoyed a flourishing society in several large cities.

Saul's main contributions as king–his military successes–are dubious as well. It is likely Saul's battles against the Moabites, Edomites, and Amalekites were actually carried out by David and attributed to Saul by an author who needed to have something to say about a king they didn't know anything about. Foreign wars such as this seem extremely unlikely when the immediate threat of the Philistines was so pressing. By pretty much any measure, Saul–if he even existed at all–was a failure as a king.