The Untold Truth Of Angel Island

Though it's often called the "Ellis Island of the West," the real history of Angel Island is significantly different compared to its Atlantic counterpart. Located within sight of modern-day San Francisco, Angel Island has actually been in use for thousands of years. But its most well-known history is surely its time as an immigration station and detention center, which would ultimately see more than 300,000 people past through (via NPR).

Unlike Ellis Island, which primarily saw immigrants of European descent, History reports that the vast majority of people processed through Angel Island were from Asia and then mostly from China. Racist attitudes and highly restrictive legislation like 1882's Chinese Exclusion Act made it especially difficult for Chinese immigrants to enter the country. Those that did were subjected to long, intensive interviews, physical exams, and open-ended stays at the island's crowded and poorly maintained immigration station. By contrast, it was more likely for European entrants (of which there were a few over the decades) to bypass Angel Island entirely with a simple check of their papers.

All told, Angel Island is now packed full of history. From its early days as a hunting and foraging ground for the local Miwok tribe, to its time as a facet of U.S. immigration history, to the brief period where it hosted the U.S. military and some Nike missiles, visitors are presented with a dizzying array of information. Here's the untold truth of California's Angel Island.

Angel Island was originally Miwok land

Located within sight of modern-day San Francisco, Angel Island was traditionally used by the Coast Miwok native people for fishing, hunting, and foraging, according to the Angel Island Conservancy. Though it appears that Coast Miwok people mostly lived on the mainland, they would make the crossing to the island using reed boats, which were pretty well suited to making the relatively short crossing over to the island. Once there, they established camps to fish and hunt some of the rich game resources nearby, which included deer and seals, as well as a seasonal glut of salmon that ran through the strait between Angel Island and the mainland. Some plants, like irises and the galls from oak trees, would also have been foraged for medicinal purposes. As far as anyone can tell, the Miwok only ever built temporary structures on the island and didn't establish any permanent settlements there. Instead, they lived in temporary structures made in part with the same reeds that formed their short-range boats.

Things began to change dramatically when Spanish colonizers took over Angel Island in the late 18th century, per the National Park Service. At that point, many Coast Miwok were already caught up in the Spanish mission system or pushed out of the region. British and Russian sailors also used the area, with one damaged ship giving Raccoon Strait its modern name after anchoring there in 1814. The Russians, meanwhile, mainly concentrated on hunting sea otters for their furs.

The U.S. government took control of the island in the 19th century

In 1839, Antonio Maria Osio must have thought that the matter of who owned Angel Island was pretty clear to anyone who bothered to ask. As the National Park Service reports, he had just gotten permission from the Mexican government to take over Angel Island that year, after asking for the land grant in 1837. In the years that followed, Osio was able to establish a fairly sizable ranch that eventually grew to an estimated 500 head of cattle, with some land reserved by the Mexican government for use as a fort. For his part, Osio grew pretty rich and socially prominent from both his holdings on Angel Island and other properties he owned in the rest of Mexico-held California.

Then, war came and changed seemingly everything. During the Mexican-American War, Osio fled the region. In his absence, the U.S. Navy occupied Angel Island and quickly did away with Osio's cattle. With the end of the war, Angel Island eventually became U.S. territory, but not everyone agreed on the result. Osio, returning from a sojourn in Hawaii, was embroiled in over a decade of disputes over the island.

Eleven years later, the U.S. government still claimed that his land grant was invalid, namely because only the governor had officially signed off on the affair and not other Mexican officials. The U.S. refused to return the island and Osio himself settled in Baja California, dying there in 1878.

Chinese immigration helped set the stage for Angel Island

To understand the full story of Angel Island, you have to reach out quite a way farther than its shores, going all the way from the interior of the United States, over the Pacific Ocean, and into the various Asian and European nations across the sea. Much of that history is concentrated on Chinese laborers, who would eventually become a controversial lightning rod and collective scapegoat for any number of American woes, from job scarcity to eugenics.

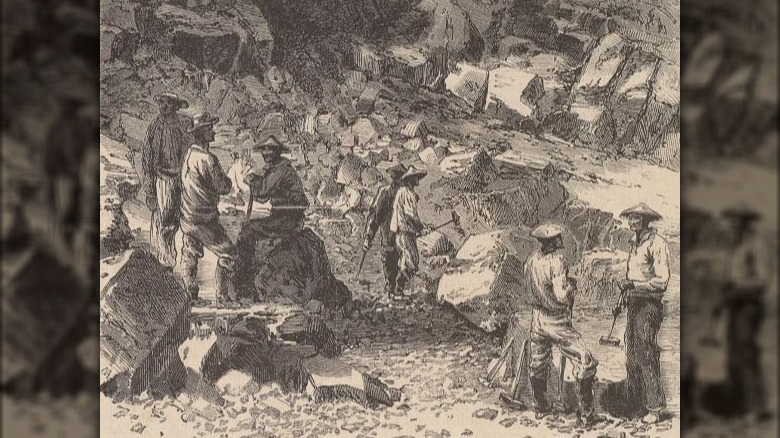

Beginning in the 1850s, as the National Park Service reports, Chinese immigrants traveled to the U.S. to labor in the mining, agriculture, and construction industries. Some of those infrastructure efforts included setting up for the massive travel advancement that would eventually become known as the Transcontinental Railroad. Political upsets and outright war in China also pushed many individuals to flee their native country, while labor shortages in the U.S. made hiring them especially attractive.

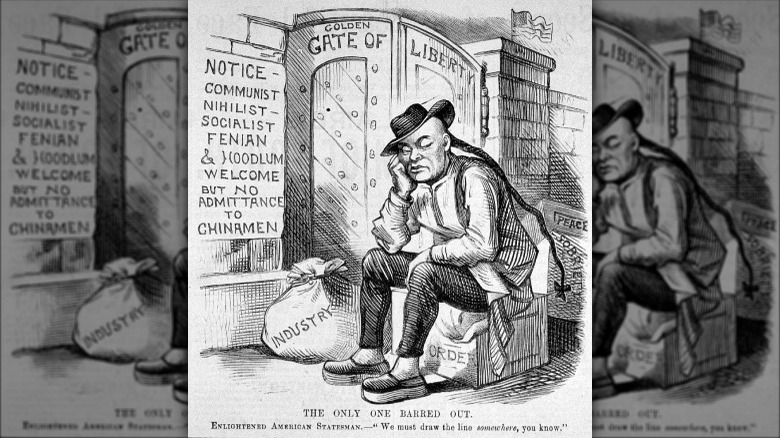

But growing racism and economic pressure turned white laborers (and voters) against the newcomers. The 1870s saw considerable money problems for the U.S., which eventually spelled poor wages and increasingly scanty job prospects for workers of all types. Many white workers, seeing lower-paid Chinese immigrants being hired instead of them, began to target the newcomers as the cause of their troubles. Some of the most racist detractors falsely claimed that Chinese immigrants were compromising the racial "purity" of the nation and lowering its moral standards (via U.S. Department of State).

Angel Island's immigration station was rooted in racist legislation

Even before it was constructed, the immigration station on Angel Island was beginning to take root in U.S. laws and bills, as well as the growing anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant sentiment in 1870s America. According to History, the first major legislation focused on this matter was the 1875 Page Act, meant to severely curtail the entry of workers of various Asian nationalities. Ostensibly, the act blocked the travel of people brought to U.S. shores without their consent. More stringent and wide-reaching laws came in 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, which almost completely blocked Chinese workers from entering the country.

Only immigrants with relatively already living in the U.S. could enter, and even then, they would not be allowed to become citizens down the road. Later, intense interviews were ostensibly meant to expose fraud like the "paper sons" or "paper daughters" who falsely claimed family relationships with existing U.S. residents.

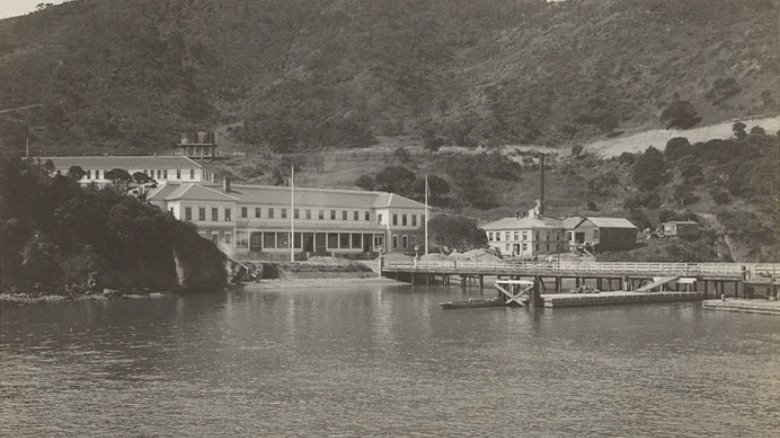

After the Chinese Exclusion Act, government officials detained Chinese travelers to question them about their intent to enter the country. This took place first on anchored ships near Angel Island, then later on the island itself. Some of the first immigrants to face questioning actually traveled to the mainland near San Francisco, where they were subjected to a stay in a "detention shed" that was notoriously dirty and full of other migrants. Angel Island, at least, would eventually have a purpose-built immigration station that opened there in 1910.

Your Angel Island experience depended on your nationality

On Angel Island, the speed and quality of your experience with immigration officials differed quite a bit, depending on the color of your skin and your nation of origin. According to History, European immigrants, who were in the minority at Angel Island, typically had the easiest go of things. Along with first-class passengers, they would move rather swiftly through the checking process and be allowed to the mainland in short order. For most of the history of the immigration station, there were few things that would keep them detained on the island for very long.

Other people, including the majority group of Asian immigrants, faced a more uncertain fate. Along with other nationalities such as Russian and Mexican people, as well as those who were placed in quarantine for what were deemed health reasons, they faced an indeterminate time on the island. Most of that time was taken up by exhaustive and presumably exhausting interrogations that zeroed in on an individual's family relationships and background in their country of origin.

Immigrants moving through New York's Ellis Island on the other coast, by contrast, would typically move through the immigration station there in a matter of hours or days. Those who were detained at Angel Island, however, could face weeks, months, or even years. They would be confined within sight of the mainland but never allowed to set their feet on it until after officials had deemed them acceptable to American society.

Conditions at Angel Island were tough

For detainees at the immigration station, life on Angel Island wasn't exactly luxurious. Per Britannica, the buildings at the station included barracks, a hospital, a bathhouse, and a laboratory, among others. Quarters were crowded and surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, says the California Department of Parks and Recreation. Windows were barred and guards made sure that doors were locked. According to Found SF, women and the children in their care were occasionally allowed to walk outside in a tightly monitored group, but no such right was afforded to the men.

Social isolation was also common. Found SF notes that men and women were typically separated, regardless of whether or not they were married or members of the same family. Visitors weren't allowed, either, supposedly because they could feed immigrants information that would unfairly allow them to pass their entrance interviews. The dormitories were spartan and poorly cleaned; at one point, a group of detainees was forced to advocate for seemingly basic supplies like toilet paper and soap.

Some immigrants were obliged to undergo invasive physical exams as well, under the explanation that parasitic diseases needed to be uncovered lest something like hookworm or live flukes spread to the rest of the mainland population. However, advocacy groups argued against some of these excuses, saying the medical exams were a thinly veiled attempt to exclude Chinese people on the basis of what were ultimately minor and easily treatable diseases (via Found SF).

Angel Island was also used as a deportation station

After all the questioning and time spent in the grim barracks, some would still be deemed "undesirable" and deported. The island was also used as a stage for deporting others throughout its history. "Resident radicals" were given the boot via Angel Island during World War I, reports the National Archives. This meant that noncitizens who lived in the U.S. during this time and who also represented an ideological threat to approved American points of view could find themselves on Angel Island. From 1917 until 1921, it's estimated that more than 60 resident aliens, as they were classified, were questioned and detained on Angel Island due to their supposedly "radical" political affiliations.

"Alien enemies" also occasionally found themselves on Angel Island during this time. This rather broad category included German passengers and sailors who were essentially caught in the U.S. at the outbreak of the country's involvement in the war, German nationals working in the Philippines (then managed by the United States), resident aliens, and even some soldiers discharged from the U.S. Army because they weren't officially citizens.

Later, Angel Island was involved in the "repatriation" of Filipinos in the 1930s. The Filipino American National Historical Society reports that, in 1934, the Tydings-McDuffie Act was the inciting event. Also known as the Philippine Independence Act, set out a timeline for an independent Philippines. It also suddenly turned many U.S.-based Filipinos into "aliens," some of whom were sent to Angel Island and deported.

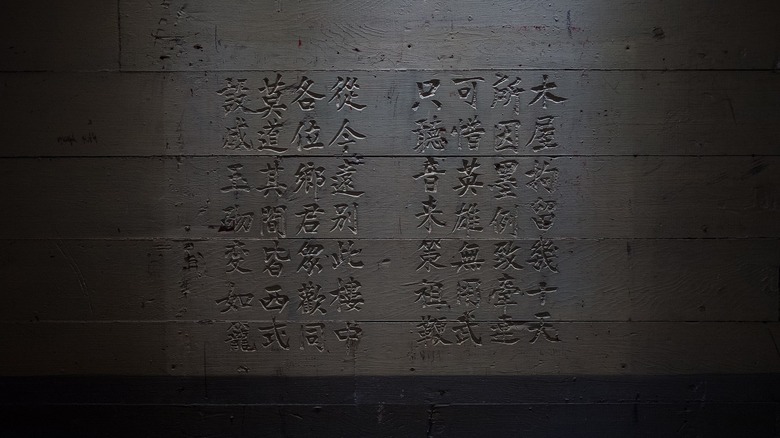

Chinese detainees left behind haunting poetry

Much of the history of Angel Island speaks to the unfair treatment of Chinese and other immigrants there, but rarely does it allow for those people to speak for themselves. While first-hand or at least personal accounts of traveling through the island's immigration station do exist, it can still be difficult to track down experiences in detainees' own words.

At least, it seemed that way until the 1970s. That's when state park ranger Alexander Weiss was evaluating the dormitory building on the island, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The parks system was planning to demolish the decaying building, but Weiss uncovered the first of what would be many poems carved into the walls. Members of the nearby community, including descendants of some of the people waylaid on the island, began organizing to preserve the station's buildings and the poetry contained on the walls inside. Now, restoration efforts have found even more of these poems, though the meticulous process means that the work is slow going, per Stanford Magazine.

To date, more than 200 individual poems have been recovered from Angel Island. While some stuck to relatively neutral topics like Chinese literature, others wrote more plainly about their time there, yearning for freedom and deploring the lonely conditions. "Sadness kills the person in the wooden building," wrote one anonymous poet (via Stanford Magazine). Very few of the poems are signed, probably to keep incensed guards and other officials from tracing the works back to their creators.

Some Jewish people fled WWII Europe via Angel Island

While it's true that Asian immigrants made up the bulk of the travelers who moved through Angel Island's immigration station, they weren't the only ones. In the years leading up to World War II, some Jewish refugees went so far as to travel across Europe and Asia, hopeful of making their way through Angel Island and into the relative safety of the United States.

They traveled in two main waves, reports The Jewish News of Northern California, with one in the 1920s after the Bolshevik revolution caused great upheaval in Russia. The second came in the build-up to World War II between 1938 to 1940. Jewish aid societies often stepped in to vouch for the new arrivals, making the experience noticeably smoother for many immigrants, at least when compared to their Asian counterparts.

It wasn't completely easy, however. According to the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, refugees like the Schott family, who arrived at the station in 1940, first had to be sponsored for a visa by family already living in the U.S. They also had to affirm that they weren't, among other things, "idiots, imbeciles, feeble minded ... or anarchists." And because they had very little money when arriving in the U.S. (the Nazi government wouldn't allow many Jewish people to leave with large funds), they were deemed at risk of becoming "public charges" and detained. They were only released when a charity donated money to the family.

The immigration station relocated after a 1940 fire

Though some of the detainees may have wished for it pretty early on in their time on the island, the end of Angel Island's immigration station didn't come until 1940. That's when a fire seriously damaged the station's administration building, forcing the whole operation to move to nearby San Francisco a few months later, as the National Park Service reports. Immigrants would now be processed on the mainland.

After the immigration operation moved, Angel Island briefly became a U.S. Army station, though it turned out to be a fairly short-lived mission. The military pulled back significantly from the island in 1946, closing its installations there and winnowing its presence down to a minimum. According to the California Department of Parks and Recreation, the island and its few inhabitants also played host to a Nike missile base in the 1950s and 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. Beginning midway through the 1950s, portions of the island were decommissioned and progressively opened to civilian visitors.

The military life of Angel Island finally came to an end in 1962, when the last portion of federal land was granted to the state of California (via National Park Service). Today, it's officially Angel Island State Park, where visitors can view the exceedingly close-quartered environment of a recreated dormitory, along with visiting exhibits and taking guided tours of the now historic immigration station.