The Myth Of Typhon Explained

Greek mythology is filled with all sorts of conflict. Mortals fighting with other mortals — like with the Trojan War — or demigods and heroes facing impossible challenges, fighting great beasts, and becoming legends in their own right. In all honesty, it's often the gods who originally created all the problems that humans eventually had to deal with.

But for all that the Greek gods have a tendency to meddle and mess with mortal lives, on occasion, they find themselves in a tricky situation of their own. Sometimes, it's just the drama that comes with a family as dysfunctional as that of the Greek pantheon, but at other times, it's having to deal with the literal deadliest monster in all of history.

That's right. Medusa, the Minotaur, the Cyclopes, the Hydra — all of them can stand aside, because they've got no claim to the title of "deadliest monster in Greek mythology." That title can only belong to Typhon — or Typhoeus, depending on what source you're reading — due to the fact he very nearly unseated the Greek pantheon as it's known today. For once, the Greek gods feared for their lives, and Zeus was nearly dethroned, all because of a single creature. Seriously, Typhon didn't mess around.

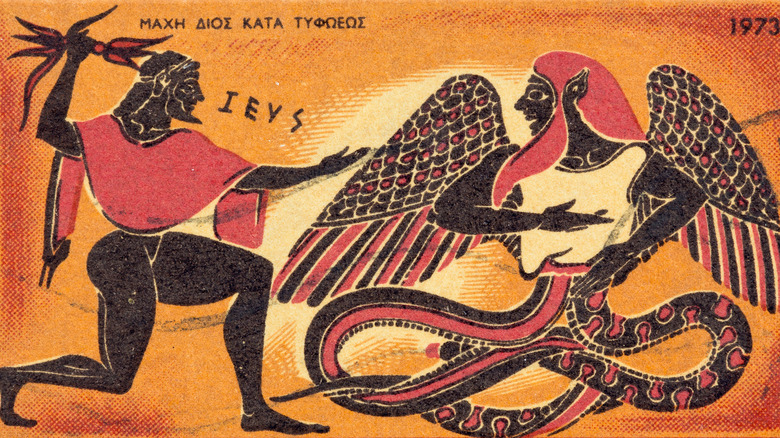

Typhon's appearance was grotesque

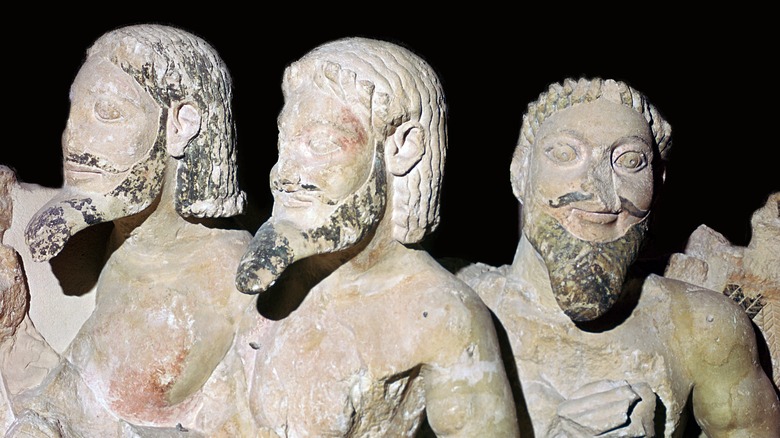

Just about every time you see Greek mythological figures depicted in art, you're usually treated to the stereotypical heights of beauty, right? After all, the Greek gods and heroes were just so great; clearly, their image would align with that. But as for Typhon? Well, Typhon was very different.

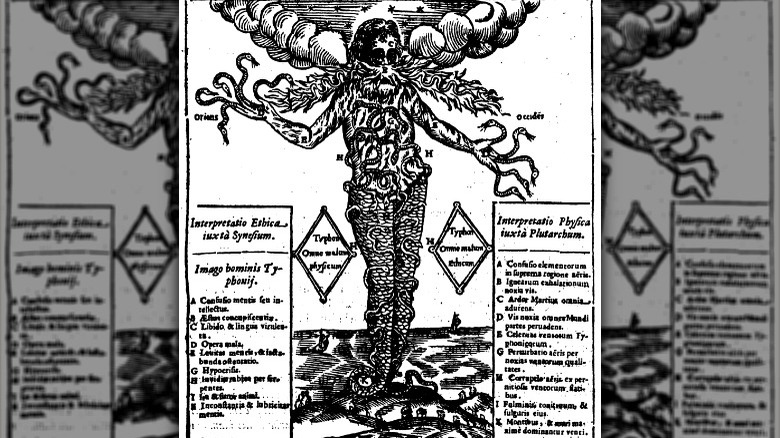

He was a monster (the deadliest of all time, according to Greek Mythology), and that's not an exaggeration. The actual descriptions of him in myths are grotesque. Hesiod describes him (via Theoi Project) as a monstrosity with a hundred dragon heads spouting from his shoulders, his eyes burning bright with fire and voice screeching loud with all manner of inhuman sounds. (Imagine every single animal you can think of, all screaming their lungs out at the exact same time. It's awful, and more or less how Typhon sounded.) Pseudo-Apollodorus added that he was "so large that he extended beyond all the mountains while his head often touched even the stars." Keeping on brand with the reptilian theme, snakes curled down his legs which, according to Nonnus, spit out tendrils of foaming poison. And that's not even it for the poison; he himself could spit the liquid from his lips, and it dripped down from every strand of his matted hair, raining down on the ground that was crushed beneath his massive feet. In short, he was, more or less, a mash-up of every terrible thing you could think of, all wrapped up in a single being.

Typhon fathered many famous monsters

Half of the fame in Greek mythology has to go to the famous and glorious heroes that everyone has heard plenty about: Hercules, Perseus, Achilles — the list of these timeless names goes on and on. But just as famous as these heroes are the monsters that they fought. After all, who hasn't heard of the Minotaur or Medusa or the giants? These monsters are about as iconic as the heroes who slew them, and many of them have Typhon to thank for their existence.

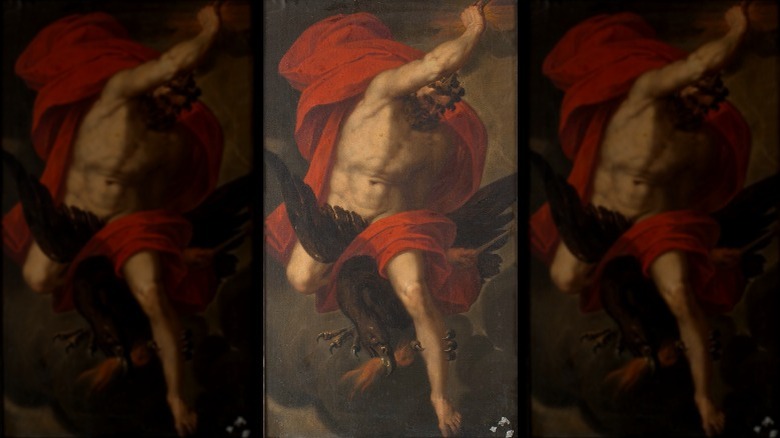

Despite his fearsome appearance, Typhon did find a wife: Echidna, known as the "mother of all monsters" (via Greek Mythology). And, knowing that, it follows that Typhon became known as the father of all monsters, the two of them giving birth to some of the most iconic creatures ever. Among them? The Sphinx, known for her notoriously difficult riddles and slain (or, rather, defeated) by Oedipus. The Nemean Lion, whose indestructible skin couldn't save it from death at the hands of Hercules during his Twelve Labors. Cerberus, the three-headed — or 50-headed, if you ascribe to Hesiod's version of the myth (via Theoi Project) — hound of Hades. And the Chimera — part-lion, part-serpent, part-goat, all fire-breathing monstrosity. Pseudo-Apollodorus even notes Typhon and Echidna as the parents of the eagle known for eating out Prometheus' liver for the rest of time. Regardless of Typhon's own fame, his progeny really made a name for themselves.

Typhon was born to defeat the gods

To fully understand what Typhon's entire deal was, you need to hop a little further back into mythological history. Back to the time before the Olympian gods — the time of their predecessors, the Titans.

As explained by Greek Mythology, the original ruler of the universe was Uranus — the Greek personification of the heavens (via Britannica) — but he was shortly overthrown by his children, the Titans. His son Cronus took power, but feared losing power to his own children, leading him to cannibalize all of his own kids. That is, except for Zeus, who was hidden away. Jumping forward in time, Zeus eventually returned to free his siblings, and all-out war raged between the Olympian gods and the Titans. This conflict — also called the Titanomachy — went on for ten years and ended with the triumph of the Olympians.

But not everyone was exactly happy with that. Hesiod (via Theoi Project) cites the defeat of the Titans as the catalyst for Gaia (the Earth, and also the mother of the Titans) to fall in love with Tartarus; Pseudo-Apollodorus gives credit to the fall of the Giants, but either way, she wasn't too happy with the end of the Titanomachy. Many of her children had been sentenced to punishment by the Olympians, and so in retribution, she gave birth to Typhon, who, according to Virgil, was intended to "break down Heaven."

Typhon fought the gods ... and won

In most mythologies — Greek mythology included — there are plenty of triumphant stories of heroes overcoming hardships and struggles only to come out on top. The Greek gods very much fit that mold: all-powerful and deserving of the utmost respect, even despite their flaws.

But Typhon showed up to change everything. He'd been born to take down the gods, and — in at least one version of this myth — he actually didn't fail.

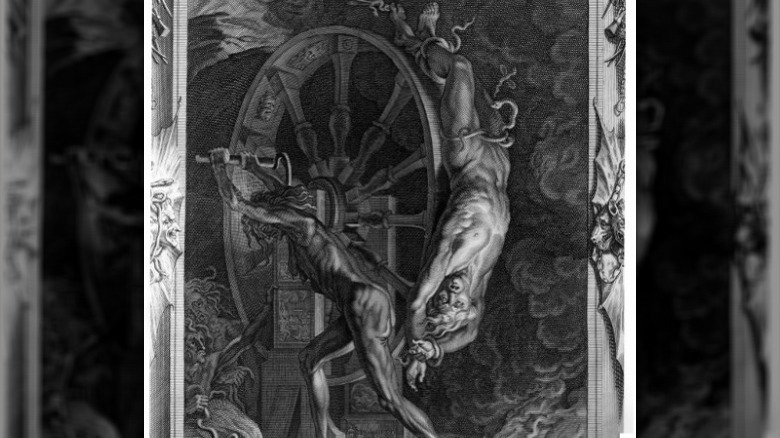

According to Pseudo-Apollodorus' "Bibliotheca" (via Theoi Project), most of the Olympians just fled at his approach. But not Zeus, who fought back, using both his thunderbolts and "a sickle made of adamant." At first, things seemed to be going in Zeus' favor, but as he was about to strike the final blow, Typhon rallied. He grappled Zeus before wrestling the sickle away, using it to "cut out the sinews from Zeus' hands and feet." Typhon carried the incapacitated god across the sea and deposited him in the Korykian cave, taking care to hide the sinews — or tendons, in more recognizable terms — far away (and inside of a bear, just for good measure). For all intents and purposes, it honestly looked like Typhon had dethroned the king of the gods — not the sort of achievement that just anyone could boast.

Many of the gods fled to escape Typhon

There's a decent chance you know that the Greek gods and the Roman gods are basically the same. Zeus is Jupiter, Poseidon is Neptune, Hades is Pluto, so on and so forth. That isn't exactly new information. But did you know that there's actually a myth out there that claims that the Greek and Egyptian gods are the same?

Basically, once Typhon showed up on the scene, the Olympians were absolutely terrified. They knew what he intended, after all. Fearing for their lives, most of the gods — save Zeus, Athena, and Dionysus in Valerius Flaccus' account (via Theoi Project) — fled Greece entirely.

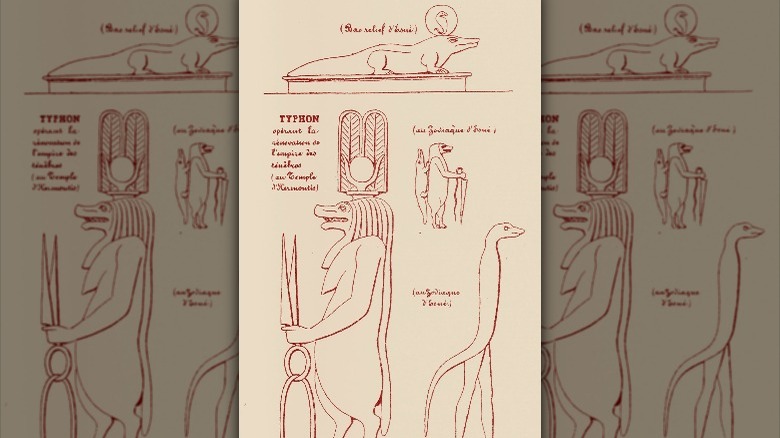

As for where they went, well, the answer was actually Egypt. The Olympians who fled from their home started donning new names and masks so that their identities could be kept a secret from Typhon. Ovid's account of the myth in "Metamorphoses" explains that "Jupiter [Zeus] became a ram ... Delius [Apollon] hid as a raven ... Semeleia [Dionysos] as a goat" and goes on to list even more of the gods and their disguises. But doesn't that sound familiar? Gods with animal heads match up perfectly with Egyptian mythology, and Greek mythology explains it as their gods in hiding. Zeus became Amon, Apollo became Horus, Dionysus became Osiris, and the pattern goes on. So, in short, Typhon was intimidating enough to ultimately spawn an entirely new religious system. Pretty wild, right?

Zeus managed to make a comeback

Given that, in the 21st century, Greek mythology is remembered with Zeus being the king of the heavens, then that has to mean that there's more to this whole story, right? After all, if Typhon just won, then wouldn't mythology have remembered him more clearly?

The Oxford Classical Dictionary explains a version of the story, saying that, after overpowering Zeus, Typhon left both the incapacitated god and his severed sinews in the Korykian cave. Helpless, Zeus couldn't do anything to save himself, but, by a stroke of luck, Hermes and Pan managed to sneak into the cave as well, stealing back the sinews and giving them back to Zeus, helping him to heal.

Back at full power, Zeus was ready for round two against Typhon, and this time, his lightning bolts proved powerful enough, striking the monster square in the chest. The force of the blow sent him hurtling beneath the earth, and, in Aeschylus' account of the story (via Theoi Project), even reduced him to ashes. With that, Typhon's time at the top came to an end.

Typhon and Mount Etna

Lots of Greek myths — and myths in general, regardless of where they originate from — work to try and explain natural phenomena in the world. The changing of the seasons, the rising of the sun, the nature of love — you name it, and mythology has an explanation for you. The Typhon myth really isn't all too different.

In the aftermath of the final fight between Zeus and Typhon, Zeus cast his enemy underground, where he would be trapped for the rest of eternity. Just to be even more safe, though, he piled an entire mountain on top of this location, according to Antoninus Liberalis (via Theoi Project), and set up Hephaestus' workshop at the peak, the god of metalwork acting as warden to their greatest enemy. Obviously, Typhon wasn't the most thrilled about this, and, per BBC, would rage against this captivity — on occasion, his temper would burn so bright that he began to spit fire from one of his many dragon heads, which would rain down on the land below.

A mountain spewing fire — sounds like a volcano, right? Well, that's because the location that Zeus chose to bury Typhon was the location of the real-life Mount Etna. Regarded as one of the most active volcanoes in Europe (and sporting a name that derives from the Greek for "I burn"), it's not too surprising that the ancient Greeks would consider the volcano's volatility to be something god-given.

Typhon might have been trapped elsewhere

While one of the more common versions of the story of Typhon has him defeated and trapped under Mount Etna, spewing lava when he's angry, that's not the only version of the tale. As per usual, Greek mythology isn't exactly consistent, and the location of Typhon's imprisonment does vary a bit.

One of the alternatives is also the simplest: Typhon was tossed down into Tartarus, the deepest, darkest segment of the Underworld, reserved just for the enemies of the Olympian gods, per Britannica. (Yes, technically the same Tartarus who fathered Typhon — Greek mythology is just like that, to be honest.) Hesiod's "Theogony" specifies (via Theoi Project) that it was Zeus who did the banishing, casting Typhon into the darkness where he would constantly fight against his captivity, inadvertently creating the "god-sent" winds that could put sailors' lives in peril while out at sea. Or, if it wasn't Tartarus itself, then there's also the possibility that he was imprisoned directly under the "mythical land of the Arimoi" — a misty, mysterious place which the ancient Greeks believed to house the entrance into Tartarus.

Another alternative is that Typhon was imprisoned in another country entirely. More specifically, he was cast underground, "engulfed in the waters of the Serbonian Lake," according to Apollonius Rhodius. Which doesn't sound all too strange, until realizing that this Serbonian Lake (or marsh, or bog, depending on what you want to call it) is actually located in Egypt, not Greece.

Greek god or Egyptian god?

As it turns out, the mythological figure of Typhon actually has a few connections with a few outside mythologies. After all, it really does start feeling like all of these stories are connected somehow.

The one that comes up the most often is Typhon's relationship to the Egyptian god Set — or Seth — whose domains included war and chaos, per the World History Encyclopedia. War and chaos and the like do seem to fit with Typhon's monstrous ways, though Herodotus (via Theoi Project) doesn't really explain much, only mentioning on multiple occasions that the two figures are one in the same. Apollonius Rhodius seems to corroborate those claims, but only by pointing out that Typhon was defeated and "engulfed in the waters of the Serbonian Marsh [in Egypt]." Britannica explains further, though, saying that around the first millennium B.C., there was a pretty big cultural shift in Egypt which led to the vilification of Set. He wasn't counted among the Egyptian gods anymore, instead becoming associated with Egypt's conquerors; this new, evil makeover led to him being more easily tied to Typhon.

Even outside of Egypt, though, Typhon seems to almost appear in other mythologies as well. According to Livius, a Babylonian epic tells the tale of Marduk — a storm god — fighting the monster Tiamat, while an Aramaean story tells of a river god (Orontes, but once named Typhon) being struck down by lightning and trapped in the earth. Sound familiar?

Typhon's parentage varies

As with plenty of ancient Greek myths, the whole story of just where Typhon comes from has gone through its fair share of different versions. In general, quite a few writers from ancient Greece and Rome agree that he's the son of Gaia and Tartarus (via Theoi Project). It fits in nicely with the whole narrative of the Titanomachy, after all.

But not all tellings of the myth are the same, with Stesichorus saying instead that he was the "son of Hera, who bore him without a father in order to spite Zeus."

Granted, that's not exactly a whole lot of detail, but a Homeric poem fills out the rest of the story. And honestly? It's sort of Zeus' fault. After all, Zeus isn't known for being faithful to his wife Hera; just take a look at all of the demigod heroes he fathered. For that matter, some of the Olympian gods are actually the result of one of Zeus' flings. Which is exactly the problem. Hera got pretty understandably angry with Zeus after the birth of Athena and vowed to get vengeance on him by giving birth to a son — albeit without ever breaking their bond of wedlock. Sounds tricky, but she left the rest of the gods and pleaded for the help of Gaia and Uranus, who did hear her cries. Gaia was moved and decided to help, and within a year, Typhon was born and ready to be "a plague to men."

Two versions of Typhon might've existed at once

As per usual, different translations and versions of a particular myth always make things complicated. In general, when you look up who Typhon was, you'd happen upon a couple of different spellings of the name — Typhon and Typhoeus being the two main ones listed by Theoi Project. In general, you can kind of ignore those different spellings and chalk it all up to translations, but in this case, there's a chance that things don't really work that way.

Hesiod in particular separates the two, saying that Typhoeus was the son of Gaia and Tartarus (or the son of Hera, if you're ascribing to the version where he was born to spite Zeus over the birth of Athena). But then Typhon was actually the son of Typhoeus, and he was the one who married Echidna and father all manners of monsters that haunt Greek mythology. The two parts of the story basically got split up into two different figures with slightly different names.

An article by The Classical Association of the Middle West and South makes similar references, citing Typhoeus again as the son of Gaia and Tartarus, the monster created to fight against Zeus and the Olympians after the fall of the Titans. But in this case, Typhon is listed as the son of Hera and created as a weird sort of parallel to Apollo, both of them being painted as sons of Zeus potentially destined for overthrowing him..