What It Was Really Like To Travel Across The US In The 1800s

One of the things we take completely for granted in the 21st century is the act of being comfortable. If you are driving somewhere, you can open or close your car windows at the push of a button. You can push another button to warm your butt. Add in modern tires, not to mention good (or at least decent) roads, and it all means a painless ride. Sure, there's plenty you could complain about, like traffic jams, potholes, the type of music your passengers are making you listen to, and how you can never adjust the seat to get the lumbar support exactly how you like it.

Well, your ancestors are rolling over in their graves, you ungrateful little – Not only did traveling back in the 1800s take tens or even hundreds of times longer than it does now, but the process of traveling was painful, uncomfortable, and very often deadly. That's right: even though we're talking about covered wagons, slow trains, and bicycles, just about every type of travel would try to kill you. So you'd spend days or weeks being uncomfortable and cold, only to maybe die before you even reached your destination.

But the 1800s was a time of immense progress. In that 100-year period, you went from people dreaming that the Industrial Revolution might make boats a little bit faster, to the first person driving a car across the entire United States. Here's what it was really like to travel across the U.S. in the 1800s.

Wagon trains and the Oregon Trail

It won't be a surprise to anyone who's a millennial that traveling by wagon train, specifically on the Oregon Trail, was a dangerous endeavor. But there was a lot more that could kill you than fording rivers and dysentery. And even if you lived, that didn't mean taking a wagon out west was at all a pleasant experience.

The Oregon Trail Center says Margaret Frink kept a journal when she and her husband traveled to California in search of gold in 1850, and that it's one of the best records we have of the experience. One average day went like this: "We started at six o' clock, forded Thomas Fork, and, turning to the west, came to a high steep spur that extends to the river. Over this high spur we were compelled to climb ... Part of the way I rode on horseback, the rest I walked. The descent was very long and steep. All the wheels of the wagon were tied fast, and it slid along the ground. At one place the men held it back with ropes, and let it down slowly." Two days later, things got worse: "It rained considerably during the night. Mr. Frink was on guard until two o' clock, when he returned to camp bringing the startling news, that for some unknown cause, the horses had stampeded."

Abigail Scott was just a girl when she was put in charge of recording her family's journey out west. One line highlights the harsh realities of the trail: "The mosquitoes are troublesome in the extreme: passed four graves."

The Cumberland Road

In a country where an interstate system of highways has been the reality for almost 100 years, it's easy to forget that means for a century and a half before that there just ... wasn't one. But once the U.S. started claiming and colonizing the West in earnest around the turn of the 19th century, they realized the lack of good roads was an issue. Suddenly people on the East Coast had reason to head west in droves, and they knew the trip would be a million times easier if there was a road.

This meant there was a big push to build said road. Known as the National Road at the time, now the Cumberland Road, it transformed the country completely. According to National Geographic, it was the first road in the new country to be funded by the federal government. Started in 1811, it was a massive undertaking which continued for decades. But as each new section was built, it opened up wide areas of the country to colonizers, allowed easier trade, and laid the literal and figurative groundwork for the eventual highway system we have today.

Even at the time, everyone knew how big a deal the National Road was. Politico reveals that by 1825, the road was so beloved it was "celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry." Can that be said about any other road besides Route 66? After all, even with all the creative types who live in Los Angeles, no one is writing love songs about I-5.

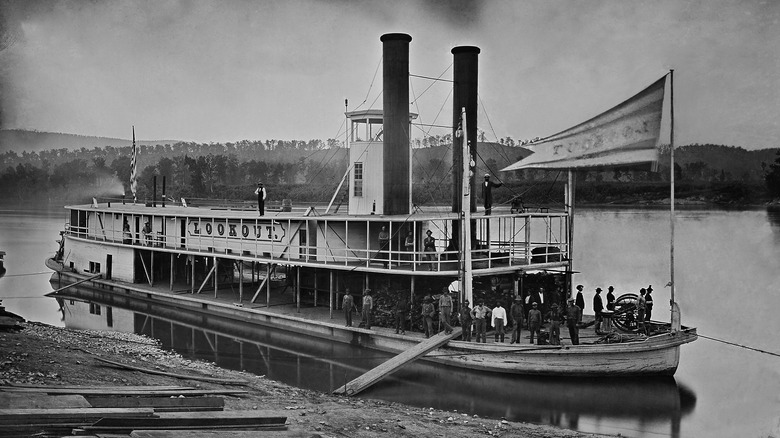

Steamboats

Surely, of all the ways to travel in the 1800s, the steamboat must have been the most pleasant. No beautiful views, nice regular pace, room to walk around on deck. Look how happy Mickey Mouse was in that cartoon! The Mississippi was the backbone of the country, and people traveled up and down it constantly.

One person who spent a lot of time on steamboats on the Mississippi was Mark Twain. His pen name even comes from his time on the river, and he wrote a memoir about his experiences called "Old Times on the Mississippi." In an except (via the New York Times), he talked about how his first steamboat experience involved some unexpected issues: "What with lying on the rocks four days at Louisville, and some other delays, the poor old Paul Jones fooled away about two weeks in making the voyage from Cincinnati to New-Orleans."

Not all steamboat trips were on the Mississippi, nor so boring. A student at Oberlin wrote a letter to his family in 1837 telling them about his dramatic journey to the college on a steamboat traveling from Providence to New York: "A sudden and severe gale struck upon us, which for a few minutes, rendered the prospects of life, hopeless. There were three or four hundred on board, I should think, whose lives were all saved by a hair's breadth. – The wind came so sudden & strong, that it tipped the boat up so much that it almost dipped, ... But while it was safety for us, others were overwhelmed in the deep."

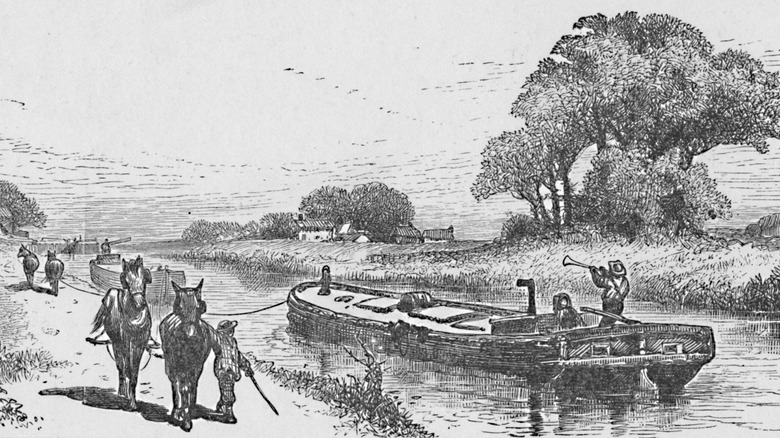

Canals

Before railroads, canals were going to be the next big thing. And they were the cutting edge of progress; Thomas Jefferson called the proposal for the Erie Canal "little short of madness," according to Eyewitness to History. Once it was finished in 1825, the Erie Canal cut the time it took to get from New York to Chicago in half, plus it was a much smoother ride than a carriage on unpaved roads.

Thomas S. Woodcock took a trip on the Erie Canal in 1836 was amazed at how nice the boat was, even though it looked so small from the outside. But, Tardis-like, somehow the inside was lovely. "These boats are about 70 feet long, and with the exception of the kitchen and bar, is occupied as a cabin ... at mealtimes ... the table is supplied with everything that is necessary and of the best quality with many of the luxuries of life."

Who wouldn't like traveling on a canal boat? Luxurious, calm, good food. And surely nothing could be safer than slowly floating down a canal. Right, Thomas S. Woodcock? You're not going to tell us that horrific deaths occurred on the boats? "The Bridges on the Canal are very low, particularly the old ones. Every bridge makes us bend double if seated on anything, and in many cases you have to lie on your back ... Some serious accidents have happened for want of caution. A young English woman met with her death a short time since, she having fallen asleep with her head upon a box, had her head crushed to pieces."

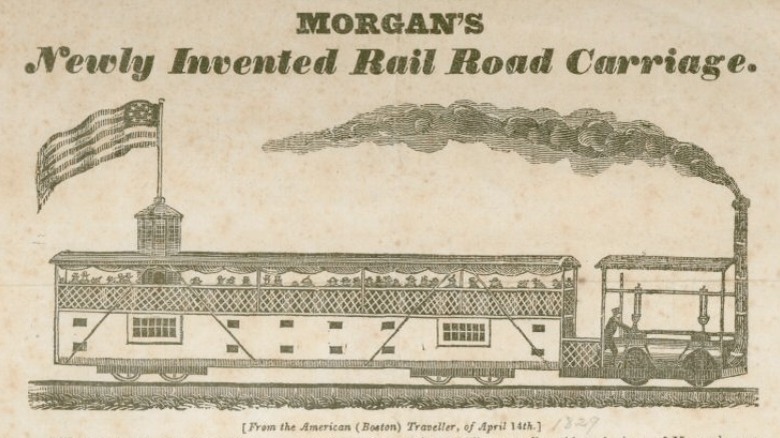

Early railroads

It cannot be overstated how important the railroad was. But in the year 1800, there were no railroads. Which meant the next 100 years involved inventing and perfecting them, but the bit in between could get a bit messy. Early railroads were not the same as the railroads travelers would enjoy at the turn of the 20th century.

Inventor Oliver Evans famously predicted in 1812, "The time will come when people will travel in stages moved by steam engines from one city to another almost as fast as birds fly – 15 to 20 miles an hour ... A carriage will set out from Washington in the morning, and the passengers will breakfast at Baltimore, dine in Philadelphia, and sup at New York the same day."

The dream began to be realized in 1827,according to the Library of Congress, when the first 13 miles of railroad track opened. The train was still only about as fast as a horse, but it was a start. What was fast was the expansion of the railroads from there. There was big money in it, no government oversight, and ridiculously half-arsed construction. This meant train derailments were common, per American Rails, and people died. Sometimes the floors of the train car would "disintegrate," with deadly results. The trips were also psychologically jarring. Railroads and the Making of Modern America explains how people's very concept of space and time was "annihilated" by the speed of this new way of travel.

Room and board

When you were traveling out west, you usually had to pack light. This meant that most people had to rely on places along the way for a place to sleep and, more importantly, a square meal. Even today stopping at a roadside restaurant while on a road trip is a gamble. Some places will be hidden gems, most ... not so much. While establishments like the St. James Hotel in Red Wing, Minnesota claim on its website today that after it opened in 1875 it was a "regular stop for riverboats and trains alike" and the guests found "modern features, including steam heat, hot and cold running water, and a state of-the-art kitchen," the general rule of stopping for food on your trip west was that it was going to be terrible.

"We found the quality on the whole bad," said traveler William Robertson, according to American Heritage, "and all three meals, breakfast, dinner and supper, were almost identical, viz., tea, buffalo steaks, antelope chops, sweet potatoes, and boiled Indian corn, with hoe cakes and syrup ad nauseam." Another man said things got worse the further west you went, when all you found were restaurants "consisting of miserable shanties, with tables dirty, and waiters not only dirty, but saucy."

But every now and then the traveler struck culinary gold ... or so one group thought. "The passengers were replenished with an excellent breakfast—a chicken stew, as they supposed, but which, as they were afterward informed, consisted of prairie-dogs—a new variety of chickens, without feathers. This information created an unpleasant sensation in sundry delicate stomachs."

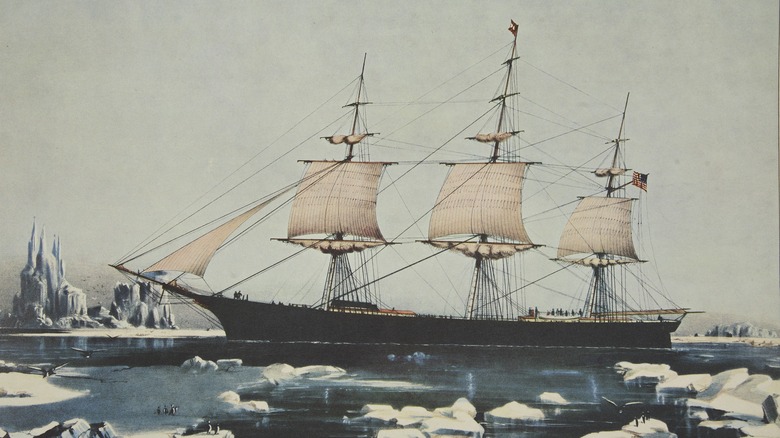

Going around Cape Horn

Possibly the main reason so many advances in getting across the country emerged in the 1800s was because the only real viable way of doing it in the first half of the century took an absurdly long time. Basically, you got on a boat and then you didn't get off again for the better part of a year.

Not that the boats didn't look pretty! One observer, writing in "The Annals of the City of San Francisco, June 1852" (via The Maritime Heritage Project) described the sight of the boats entering the Bay, "large and beautifully lined marine palaces, often of two thousand tons ... These are like the white-winged masses of cloud that majestically soar upon the summer breeze."

But for those who were on the boats, they were probably more like a never-ending hell. Going from New York to California meant sailing around the very bottom of South America, a.k.a. Cape Horn. To get an idea of how slow this was, according to Stephens & Kenau, "the fastest clipper ship ever launched" was the Flying Cloud and her stats make for depressing reading today. In 1851, the ship "reached San Francisco in a record time of 89 days and 8 hours. The average time for clipper ships being more than 120 days." Three years later the boat beat her own record by a mere 13 hours. Even more shocking, no one else would beat that time for well over a century: not until 1989. And since most people in the 1800s weren't on the Formula 1 car of boats, and even the Flying Cloud ran into major, time-consuming issues on many of her voyages, this was not sustainable.

'An Overland Journey From New York To San Francisco In The Summer Of 1859'

The most logical way to get across the country in a quicker, safer, relatively cheaper fashion seemed to be by rail. But the idea of a transcontinental railroad was almost ludicrous. Take just one of the issues you'd run into: the Rocky freaking Mountains. Considering how new the technology was even in the middle of the century, not everyone was convinced it was possible.

One person who was sure it was worth trying was the founder of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley. According to Encyclopedia.com, in 1859, he traveled across the country, writing articles about his journey for his newspaper. These were then turned into a book. Greeley wanted people to know all about the western part of the country and how awesome it was, and once they wanted to see it themselves, he'd get what he really wanted: a railroad to make the trip easier. Because Greeley had a tough time of it: a New York Times review of his book explained how "his stagecoach was overturned by buffaloes. His body was racked by boils from riding muleback weeks on end ... Fastidious about food and cleanliness, he had little chance to observe his principles about either westward of the Mississippi."

While the railroad was the most important reason he wanted people to learn about his trip west, there was another vital thing that he believed America needed to get to the frontier ASAP: "The first need of California today is a large influx of intelligent, capable, virtuous women."

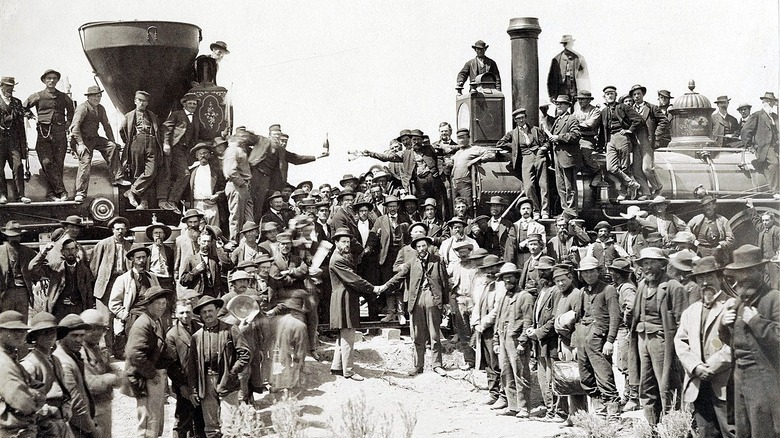

The Transcontinental Railroad

While there were plenty of railroads before the Transcontinental railroad, they were a spider web of tracks and companies, mostly relatively localized. The Transcontinental would be different, and would do what it said on the tin: connect one coast to the other with railroad tracks. Technically, track only needed to be laid from Nebraska to California, and in 1869 it was finished. Now people could travel that 2,000 mile stretch in just a matter of days, according to History. Seven years after the Transcontinental railroad was finished, an express train made the journey in 83 hours.

It was not only faster, but impossibly more comfortable. "I had a sofa to myself, with a table and a lamp," wrote one rider (via American Heritage). "The sofas are widened and made into beds at night. My berth was three feet three inches wide, and six feet three inches long. It had two windows looking out of the train, a handsome mirror, and was well furnished with bedding and curtains." A reporter from the New York Times wrote it was "not only tolerable but comfortable, and not only comfortable but a perpetual delight. At the end of our journey [we] found ourselves not only wholly free from fatigue, but completely rehabilitated in body and spirits."

Of course, no long journey is perfect. In 1972, one traveler said the train trip "caused more hard words to be spoken than can be erased from the big book for many a day."

Getting across the country by (wo)manpower

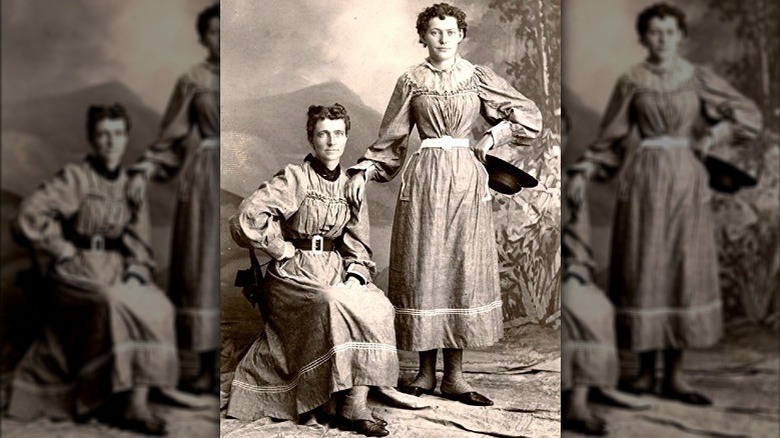

One of the most extraordinary journeys that was undertaken during the 1800s wasn't from east to west, and it wasn't undertaken by a man.

An article in the San Francisco Call from May 5, 1896 explained the crazy plan: "Mrs. H. Estby and her daughter, aged 18, leave tomorrow morning to walk to New York City. They are respectable but will 'rough it' as regular tramps and carry no baggage." Respectable women walking alone across town was scandalous, let alone doing something no one had ever tried before. (Although Frank Weaver had made a cross-country trip by bicycle in 1890.) But times were hard, and the women had good reason, since "Mrs. Estby is the mother of eight children, all of whom are living with their father on a ranch near here, except the one going with her. The family is poor, and the ranch is mortgaged. Mrs. Estby, seeing no other way of getting out, concluded to make the journey afoot."

How would walking across the country save the farm? Well, some person or group or company (unfortunately this detail was lost somewhere over the past century, according to Transportation History) was offering $10,000 to the first woman to accomplish the feat. For seven and a half months, going around 30 miles a day, working along the way to pay for food and board, the mother and daughter made their way to New York ... whereupon the sponsors refused to give them the prize on a technicality, and wouldn't even pay for the women to get home.

The first cross-country car journey was the end of an era

You could argue that in Britain, the 19th century didn't really end until 1901, with the death of Queen Victoria. In America, the key date could be seen as 1903, when the first person crossed the country by car. This signaled a new era, one where the West was no longer wild or out of reach to anyone. The continent had been crossed by foot, wagon, train, and now the newfangled car was added to the list.

H. Nelson Jackson, a doctor, and Sewall K. Crocker, a mechanic, drove from San Francisco to New York City after Jackson's friends said they didn't think it was possible. "The majority opinion expressed was that, save for short distances, the automobile was an unreliable novelty," Jackson would later explain (via SFGate). "Everyone pooh-poohed the idea of even attempting such a journey." So the two men and a dog named Bud set off.

While no one today would consider their trek easy, they managed it without major issues in just 63 days. Jackson spent $8,000 on the trip, which was a lot of money back then, but that number does include the cost of the car. Others were inspired, and copycat cross-country trips started by the dozens. The trip "was a pivotal moment in American automotive history," said Roger White, curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. "At the time they made the trip, there was a perception that the American frontier was closed. The Jackson-Crocker trip excited people across the nation. It got people thinking about long-distance highways."