What You Probably Didn't Know About Covered Wagons

Safety in numbers. Or, if you prefer, misery loves company. Either way, the great Western Migration of the 19th Century was largely accomplished by people crossing the Great Plains, bound from the East, or even what's now the Midwest, en route to the lush lands of Oregon and California, there for the taking, there for the settling — if you survived the trip.

There was no easy way to make a new life for yourself in the 1800s. Not if you wanted to move, and not if you wanted to move a family. Passage by ship around the tip of South America was an expensive and dangerous option. Railroads? The transcontinental railroad wasn't completed until 1869, according to History. Stagecoach? Impractical for families, plus what they might need when you got where you were going — tools, household goods.

Not that the alternative was a whole lot better. While many of the Latter-day Saints made the trip to Utah using handcarts (and walking), relates Historynet, many others would invest in a covered wagon of some kind. There were various sizes available, and of course in this case, size actually mattered — because you had to take into consideration how you were going to move that wagon, loaded up with supplies, tools, and household goods with which to make your new start in a new land.

Most people walked most of the way

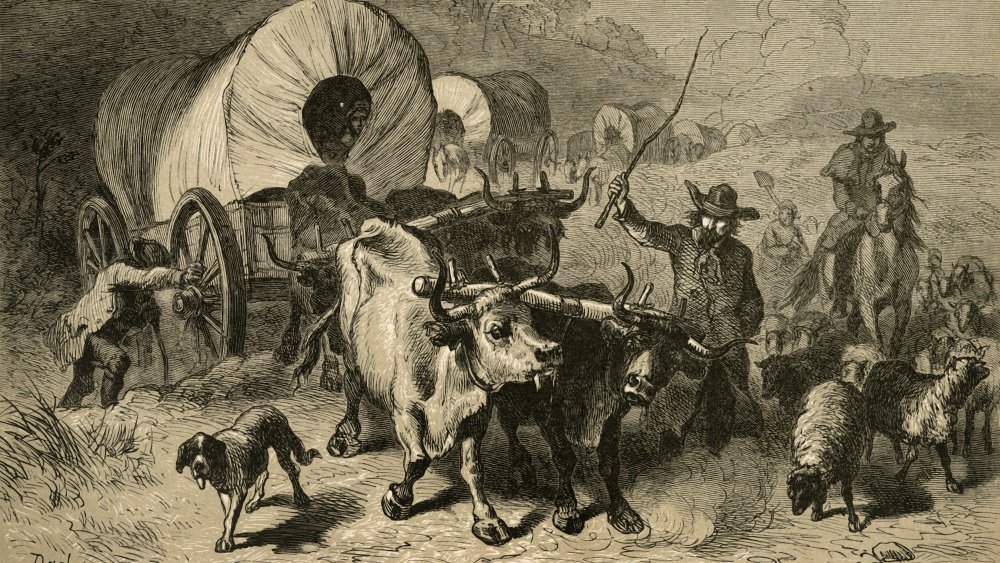

They would travel in packs — wagon trains, a collective of like-minded folk, guided by someone who claimed to know where they were going and the best way to get there (though that didn't always work out — ask the Donner Party). Migration began in earnest with the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in the 1820s, then picked up considerably with wagons headed for Oregon and California in the 1840s, writes Marshall Trimble in True West Magazine. The first wagons generally measured about 10 feet long, four feet wide, and two feet deep, writes Jana Bommersbach, also for True West. Arches over the top of the wagon were covered by heavy canvas. The incredible weight being moved required significant animal power, and so most often, wagons were pulled by teams of oxen, though occasionally mules or horses were utilized instead. Added benefit: an ox wasn't a very attractive target for thieves — they moved slowly, you couldn't ride them, and not particularly tasty. As the trip wore on, and the oxen wore out, it was not unusual for families to start abandoning the things that seemed so important before they left.

The so-called Conestoga wagon was extremely popular until the 1850s — as popular as something as primitive as this could be, anyway — rugged, dependable, and incredibly uncomfortable. One advantage of using oxen was that the family could walk alongside at a relaxed pace.

Wagons were built to endure

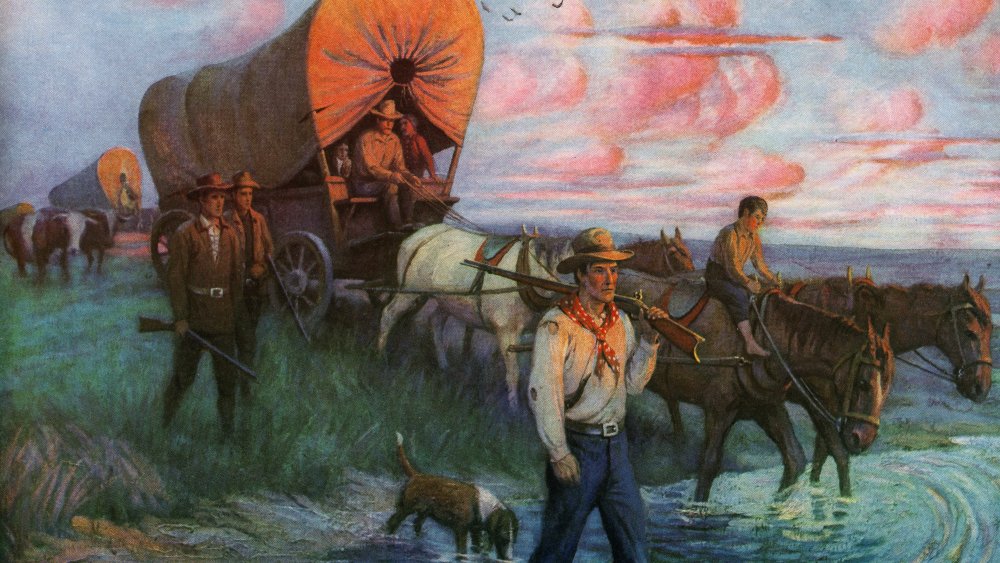

On a good day, a wagon train might cover 20 miles — seven days a week, with no holidays, trying to take advantage of good weather before autumn and winter struck, trying to cover some 2,000 miles in about five months. There was a break for lunch, then the evening stop for the night, with beds unrolled underneath the wagon — there wasn't room within for people. Repairs had to be done on the road. The wagons had springs, but if you did try to ride, it was a bone-jarring trip and most people didn't bother. Advancements in wagon design — it's probably a stretch to call it "technology" — resulted in the slightly smaller, perhaps faster, "prairie schooner," replacing the Conestoga in the middle of the century.

Wagon trains, especially the larger groups, were rarely attacked by Native Americans. More problematic was the weather. A swollen river could prove impossible to cross, causing days, even weeks, of waiting. Muddy ground could slow progress. And if the guide was inexperienced, there was always the nightmare of getting lost, losing time, and getting stuck. (Donners, anyone?)

The voyage completed, the wagon often served as temporary shelter

Once arrived in the new territory, the wagon would provide the first shelter for the family, until something a little more permanent could be built, whether of timber or simply prairie sod. The vehicle itself would continue to be used to move what needed moving as the family settled in.

Texas rancher Charles Goodnight is credited (by some) with inventing another form of Old West wagon: the chuckwagon, a rolling kitchen serving the needs of cattle drives. The cook would drive the wagon ahead of the herd during the day, meet up to serve hot food, move ahead again to prepare for the evening, while gathering firewood and perhaps fresh game or even wild bird eggs along the way. It was smaller than the prairie schooner or the Conestoga, and would feature fold-down work spaces, maximized storage for cooking equipment, and no matter who invented it, was generally an ingenious piece of American engineering.