Little Known Facts About Acting Legend Sidney Poitier

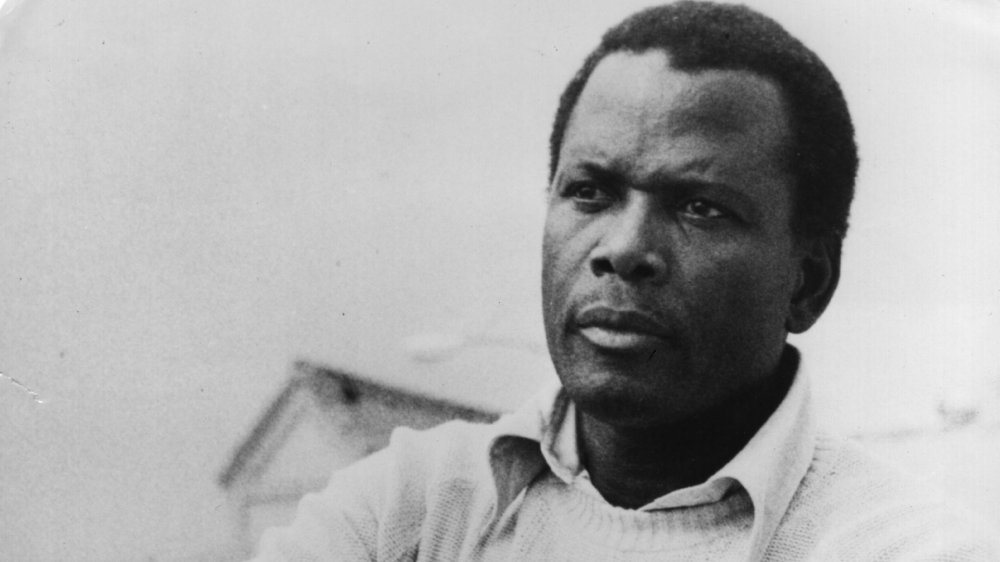

While Sidney Poitier was far from the first Black actor to appear on the big screen or gain popularity with an interracial audience, his career marked a turning point for African Americans in the media. During the first half of the 20th century, if Black actors were used (instead of white actors in blackface), their characters portrayed demeaning and stereotypical roles.

Lincoln Perry, considered America's first Black film star, represented Old Hollywood's ideal role for a Black actor. His "Stepin Fetchit" character was popular enough to see Perry become a millionaire at the height of his fame in the mid-1930s, according to NPR. Said character, unfortunately, gained success by playing up the stereotype of a mumbling and lazy Black man. Behind the camera, Perry fought unsuccessfully for equal pay to his white co-stars and eventually left the industry. Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win an Academy Award in 1940 when she won Best Supporting Actress for Gone with the Wind. But like Perry, her role was stereotypical, this time as "Mammy," which Ferris State University states was supposed to prove "that blacks — in this case, black women — were contented, even happy, as slaves."

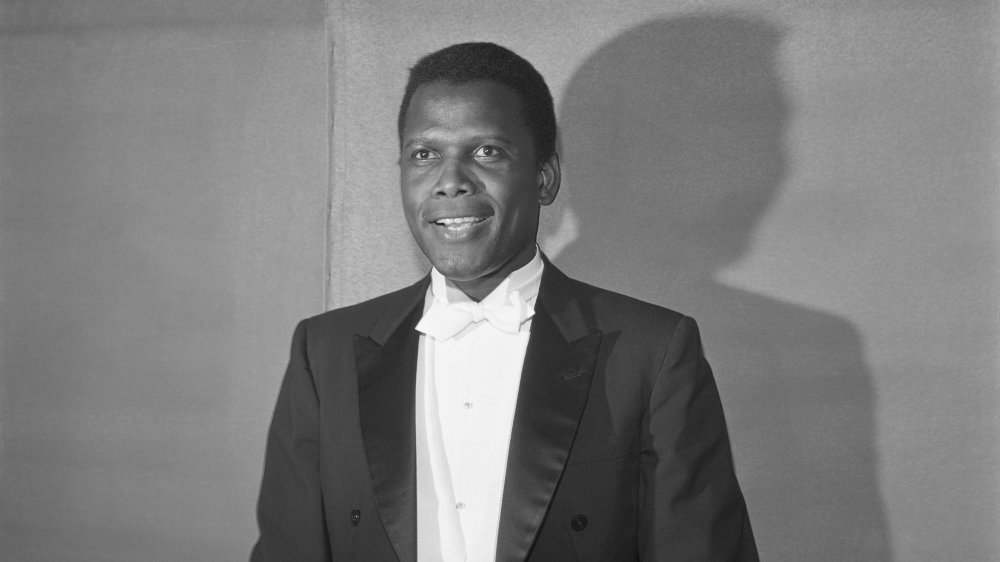

When Sidney Poitier broke to the mainstream in the 1950s, walking in step with the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, he bought a new and proud image of African Americans and new dreams for the country. Sadly, the legendary actor passed away January 7, 2021, reports NBC News. He was 94. Here are some little-known facts about the acting legend.

Sidney Poitier almost died at birth

Sidney Poitier worked in the movie industry into his 80s, a true testament to his longevity and endurance. It's even more outstanding considering that Poitier wasn't expected to see the outside of the hospital in which he was born, let alone a Hollywood studio.

According to People, Poitier's parents were immigrants from the Bahamas who happened to be in Miami when his mother, Evelyn, went into labor two months early and gave birth to her youngest child. The chances for Poitier to survive were so low that his father, Reginald, had returned home to the Bahamas with a shoebox to bury his son. However, the future movie star survived, and soon, the family returned to their farm on Cat Island in the Bahamas, where Sidney would spend the first decade of his life.

As reported by Vanity Fair, Poitier talked about how his skin color was never a concern while living in the Bahamas. Poitier eventually moved to Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas, at the age of ten. Vanity Fair says that at 15, because of his parents' age, he was sent to live with his older brother in Florida, where the teenage Poitier finally came face-to-face with institutional racism. It "baffled" Poitier, who moved up north to New York City within a year, with the words of his mother, "Charm them, son, into neutral," in the back of his mind.

Sidney Poitier had to change his accent

When the Beatles made their journey across the Atlantic to the United States, their English accents made them unique and attractive to the American public, The Independent notes. The same cannot be said for Sidney Poitier and his Bahamian accent. Black actors from the United States already had trouble finding success in their home nation, so a darker-skinned man from another country like Poitier had another barrier to overcome.

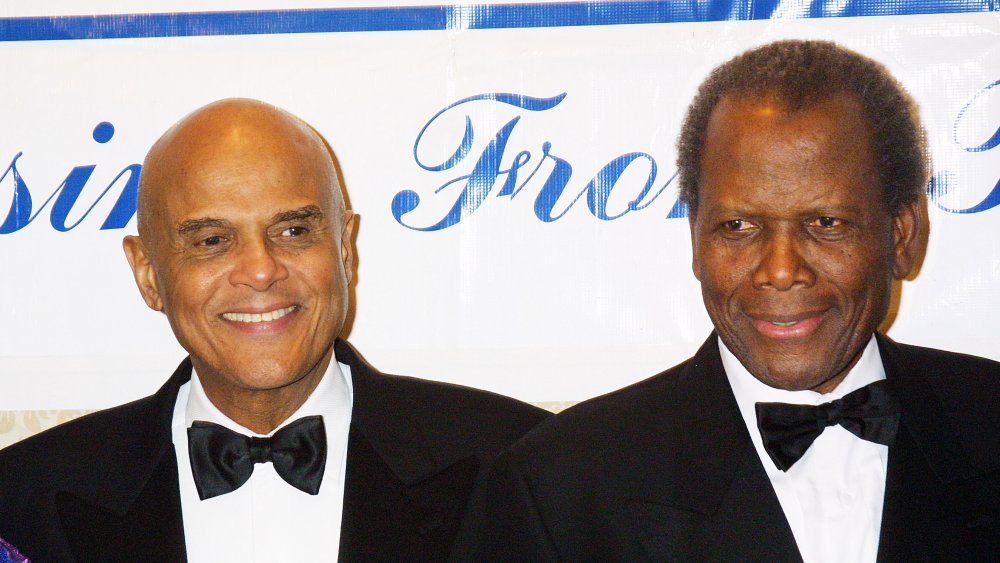

According to Britannica, after a stint in a medical unit during World War II, Poitier applied to the American Negro Theatre. The ANT, as reported by Black Past, ran from 1940 to around 1955 and helped train and shape some of the finest African American actors of the next decades, such as Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Alice Childress, and Poitier. One of the main goals of the company was to "to produce plays that honestly and with integrity interpreted, illuminated, and criticized contemporary black life and the concerns of the black people," a practice that Poitier and the other actors of the ANT would continue during their careers.

However, the studio did not accept his application at first, in part because of his strong accent. This led Poitier to spend the next six months trying to rid himself of his accent. He did so by practicing American enunciations by listening to the radio, Britannica states. Six months later, he was accepted, and in 1946, he made his Broadway debut in Lysistrata.

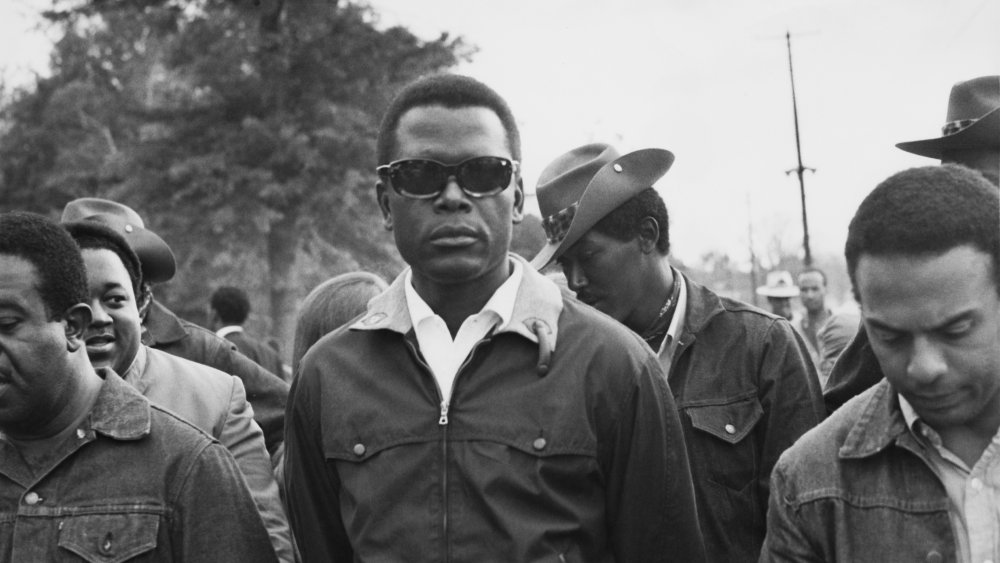

Sidney Poitier fought for civil rights

The deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor have sparked many Black celebrities to use their platform to push a message of social justice and equality, but this is not a new practice. The Civil Rights Movement was one of the earliest examples of Black celebrities openly voicing their anger and hope for the nation. Sidney Poitier was one of the loudest voices of the era in this regard.

Poitier, along with his friend and ANT alumnus Harry Belafonte, became two of the most recognizable celebrity faces during the Civil Rights Movement. According to a New York Times piece about their friendship, Belafonte convinced Poitier to help him bring $70,000 to the Freedom Summer activists in 1964. The two were met by Klansmen firing guns at their vehicle when they entered the South. Poitier and Belafonte helped organize the March on Washington the previous year, as well as the funeral for Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, the article reports. King said this of Poitier: "He is a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom."

Poitier also used his acting to portray Black characters not as classic stereotypes such as Stepin Fetchit but instead as more dignified and professional in order to change the image of his people in the public eye. Despite this, Poitier would receive criticism for his characters being, as an AP News article says, "too perfect," rather than believable.

Sidney Poitier made history at the Academy Awards

Sidney Poitier spent his early career fighting back against negative, stereotypical roles that African American actors were given. In his first credited film appearance, No Way Out in 1950, he played a doctor who had to treat a white bigot, and he continued to climb the acting ladder throughout the 1950s. In doing so, Poitier set the standard for Black actors to be taken as serious contenders for awards.

His 1958 film, The Defiant Ones, again saw Poitier's character having to work with a white bigot, played by Tony Curtis, this time as escaped prisoners chained together. The role landed Poitier his first-ever Oscar nomination, for Best Actor. It was the first time a Black actor had ever been nominated for the award.

By 1963, Poitier had become an established Hollywood actor with a string of commercial and critical successes such as A Raisin in the Sun and Porgy and Bess, both of which led to Golden Globe nominations for Best Actor. That year, Poitier starred in Lillies of the Field, an adaptation of the William Edmund Barett novel of the same name. The performance led Poitier to become the first African American to win Best Actor at the Academy Awards, in addition to a Golden Globe. Not since Hattie McDaniel won Best Supporting Actress with her role in Gone with the Wind had an African American won a Best Acting award at the Academy Awards.

"The Slap" became a landmark movie moment

Movie cops have come in all shapes, sizes, and colors, or at least that's what many people want to believe. From Ice T to Samuel L. Jackson, seeing Black cops has become common. However, because of the authority and respect that cops and detectives tend to hold, the idea of a Black police officer or detective commanding respect was once unheard-of, especially if they demanded respect from white citizens.

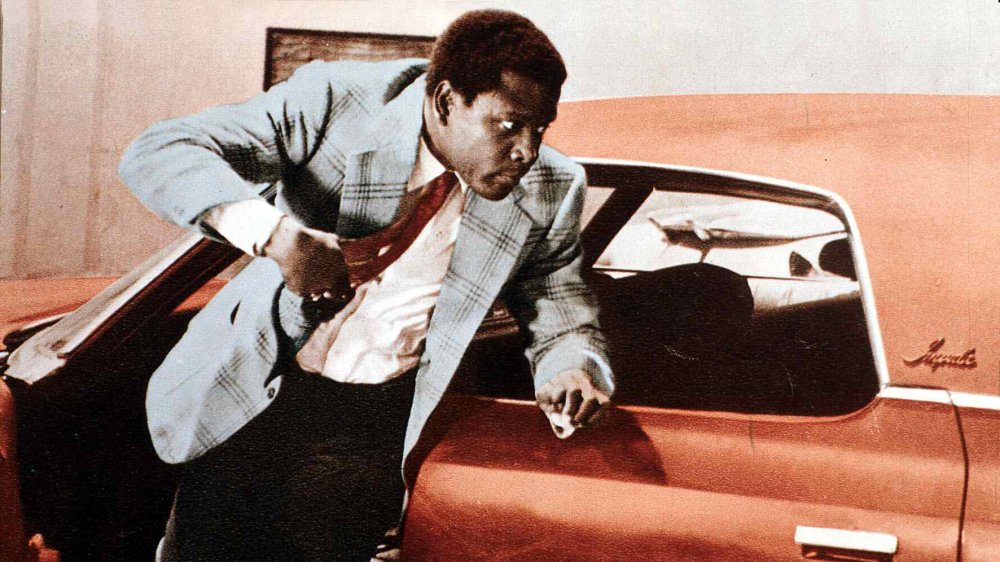

Like any racial obstacle Sidney Poitier faced, he tore through this one like an ax in the forest. In 1967, he starred as Detective Virgil Tibbs in the film In the Heat of the Night. Poitier's character travels to Mississippi to investigate a murder with the local sheriff. According to The Independent, Poitier slept with a gun under his pillow while they filmed in Tennessee before the rest of the production was moved to Illinois. During a scene when Detective Tibbs was questioning a racist, wealthy resident, the resident slaps Tibbs across the face, at which point Poitier's character slaps him back harder. The scene made the final cut of the film and became a landmark moment in cinematic history, showing a Black authority figure reprimanding a wealthy white man.

Director Norman Jewison said of the moment to The Guardian, "A black man had never slapped a white man back in an American film. We broke that taboo."

In the Heat of the Night had two sequels

The end of the 1960s saw the optimism and hope that began the decade turn more radical and violent with the continuing struggle of the Civil Rights Movement and the ongoing Vietnam War. 1967 was a blockbuster year for Sidney Poitier, with three of his most acclaimed films coming out during the year: To Sir, with Love, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and In the Heat of the Night.

With the success of In the Heat of the Night and the popularity of his character, Detective Virgil Tibbs, Poitier reprised the role on two separate occasions for sequels. First was 1970's They Call Me Mr. Tibbs!, titled so because of the famous line from the original film, and The Organization the following year. Both films, unfortunately, did not meet the expectations set by their critically and commercially acclaimed predecessor. Film critic Roger Ebert gave The Organization two stars, saying, "The plot is not exactly believable," according to his website's archives.

They Call Me Mr. Tibbs! received only a 36 percent Audience Score on Rotten Tomatoes and was 35 points lower on the Tomatometer when compared to the first film (60 vs. 95 percent). While the trilogy seemed to downgrade with each movie, the last film was a stepping stone for another acting trailblazer. The late Puerto Rican acting giant Raul Julia gave one of his first film appearances alongside Poitier in The Organization.

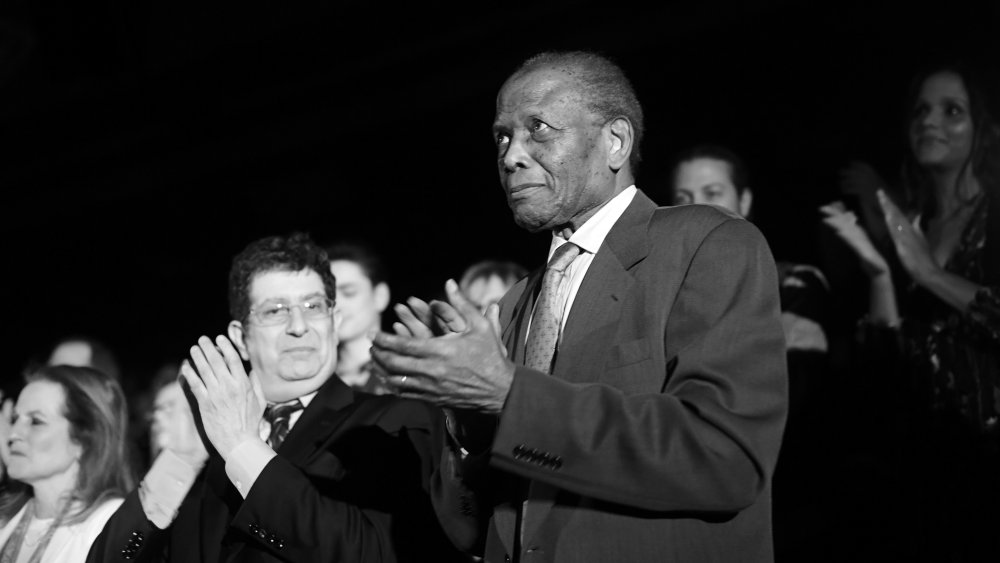

Sidney Poitier gave up acting for more than a decade

The end of the 1960s left many tough questions in the minds of Americans, Poitier included. The assassinations of Malcolm X in 1965 and Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy in 1968 left the nation and the Civil Rights Movement without a leading voice to guide the country through the turbulent times.

For Poitier, the late 1960s marked a time to reflect on his own life and career. An article in The New York Times titled "Why Does White America Love Poitier So?" made the actor question his own contributions and image he projected. The late 1960s saw a rise in Black nationalism, with less of an emphasis less on wanting to project an image that white America could respect and instead favoring self-respect within the Black community and holding an apathetic attitude on white America's opinions on Black culture. This was reflected in the term "black power," coined by Kwame Ture.

According to PBS, the criticism from the article accused Poitier of being "too passive" to the white public, leading him to retreat back to the Bahamas to reflect on his life. When he returned to the United States, he focused more on working as a director. His directed films included Buck and the Preacher, Uptown Saturday Night, and Stir Crazy. Poitier unofficially gave up acting in 1979, though he returned as an FBI agent in the 1988 movie Shoot to Kill.

Sir Sidney Poitier: international diplomat

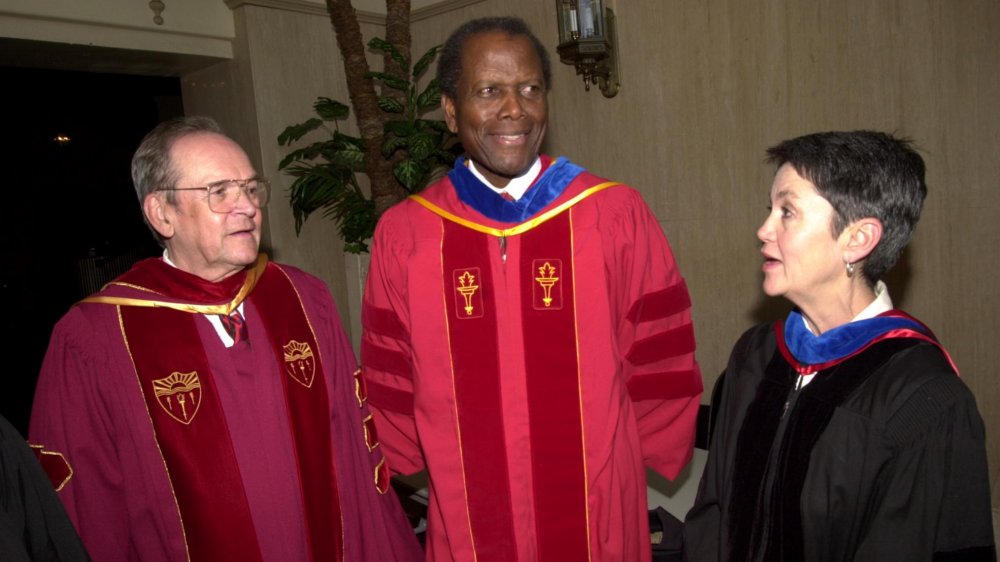

In 1974, a year after the Bahamas became an independent nation from the United Kingdom, Poitier was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. According to Achievement, Poitier does not use the title in the U.S. but is referred to in the British Commonwealth as Sir Sidney Poitier.

In 1997, at 70 years young, Poitier added a title to his illustrious career. He was named the ambassador of the Bahamas for the country of Japan. The Independent reports that Poitier, following the ceremony, presided over by Japanese Emperor Akihito, said, "It's exhilarating, it's a very satisfying feeling," Poitier continued by discussing the importance of being a good representative for his home country, a practice that he had spent his career displaying in his films: "I was raised in the Bahamas. My roots are there. I am as familiar with that society and its people as I am with America and there is in the present government a need for me to be of some service."

Despite the title and position, Poitier made it clear that his primary focus would be his career with films and not as an ambassador. The Bahamas themselves did not have an embassy in Japan. Poitier had only, at the time, made two trips to the island nation and had no intention of moving to Japan. According to the Chicago Tribune, one trip was to see film director Akira Kurosawa in 1967, and the other was a family vacation.

Sidney Poiter was a mentor to Denzel Washington

Following the death of Kobe Bryant, more came to light about the relationship between him and his role model in basketball, Michael Jordan. As reported by ESPN, Jordan would refer to Bryant as his "little brother," and Kobe called Jordan his "big brother." Denzel Washington's relationship with Sidney Poitier mirrors this master/disciple dynamic. Washington could be argued to be the modern version of Poitier, given that they're among the few African American men who've won Best Actor at the Academy Awards.

HuffPost detailed a conversation Washington had early in his career with Poitier: "I called Sidney and told him 'man they are offering me $600,000 to play the 'N****r They Couldn't Kill.' And he told me, 'I'm not going to tell you what to do. But I will tell you this, the first, two, three, or four films you do in this business will dictate how you are perceived.' He didn't tell me what to do, I give him credit for that. So I turned it down."

Poitier has played Black figures such as Nelson Mandela and Thurgood Marshall. Washington earned two Oscar nominations playing black activists Steve Biko in Cry Freedom and Malcolm X in the film of the same name. Later in his career, he starred in and directed the adapted August Wilson play Fences.

Sidney Poitier helped usher in a new era for Black actors in Hollywood

Golden Age Hollywood has been canonized the same way the Founding Fathers of the United States have been. In both circumstances, the stories told are extremely kind and meant to create a type of mythology. And both are told from a white perspective. In Old Hollywood, African Americans were subjected to humiliation and abuse, only appearing as buffoons for the delight of white audiences and to give credence to racist stereotypes.

According to The Guardian, in a 1967 interview, Sidney Poitier described the images he saw when he watched Black actors as a child: "The kind of Negro played on the screen was always negative, buffoons, clowns, shuffling butlers, really misfits. This was the background when I came along 20 years ago and I chose not to be a party to the stereotyping ... I want people to feel when they leave the theatre that life and human beings are worthwhile. That is my only philosophy about the pictures I do."

In 1992, Denzel Washington presented Poitier with the American Film Institute Achievement Award. He called Poitier "a positive example of elegance and good taste" and "a source of pride for millions of African Americans." Sidney Poitier may have not been the first successful African American film star or the first to be awarded honors, but as Washington said, he was a source of pride and a positive example for African American actors in the second half of the 20th century and beyond.