The Tragic Story Of When The British Starved Bengal

During the Second World War, Great Britain recruited over 2 million people from British India to fight in the British Indian Army, and it's estimated that at least 89,000 died during the war. And although that number is high and horrific, it's incomparable to the millions who lost their lives during the simultaneous Bengal Famine of 1943.

This famine is especially unique due to the fact that it was largely caused by British policy rather than any natural elements, leading many to describe it as "man-made." Although the food supply was certainly affected by the brown spot fungal disease and flooding, there wasn't a staggering absence of food at the time. Instead, it was inflation, hoarding, and Britain's scorched earth policy, among other factors, that resulted in millions of people being unable to access food.

Many walked for hours in search of food, seeing people on the way "lying on the fields and vultures circling them." And while the famine itself eventually subsided, the effects of the famine lingered in the region for years. However, although the Bengal famine of 1943 wasn't the first famine induced in India by the British, it did in fact turn out to be the last. This is the tragic story of when the British starved Bengal.

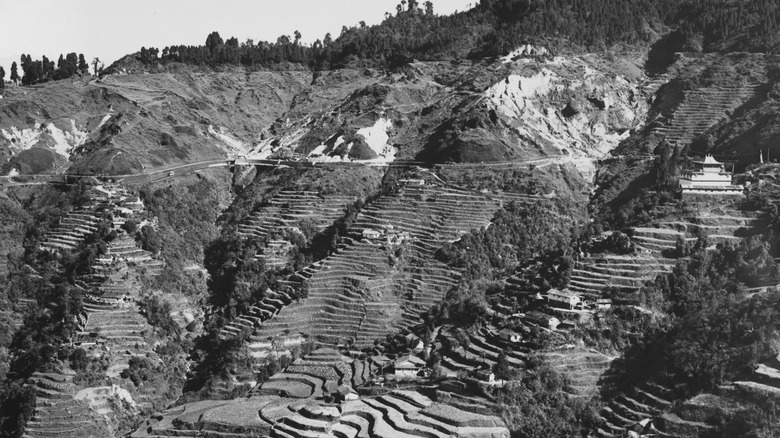

Bengal in Colonial India

After the defeat of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, in the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British East India Company took control of Bengal. According to the University of Delhi, this victory "was not a great triumph of English arms," and instead had largely to do with the betrayal of members of the Nawab's court, like Mir Jafar, who opposed him and "meticulously planned his downfall." ThoughtCo. writes that after the Battle of Plassey, the British East India Company "seized the modern equivalent of about $5 million from the Bengali treasury." And as the plunder continued over the following years, millions ended up starving. Between 1770 and 1773 alone, it's estimated that between 2 to 10 million people in Bengal died of famine as a result.

After an unsuccessful rebellion in 1857, begun by Bengali Muslim troops against the rule of the British East India Company, the British government took control over region, encompassing what would eventually become Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

In 1905, Bengal was divided by the British colonial government into Hindu and Muslim sections, known as the first Partition of Bengal. However the partition was met with widespread opposition and protest from both Hindu and Muslim people and in 1911 the partition was annulled "in the face of continuing militant public protest," according to "Emergence of the Political Subject." However, not all of East Bengal was reunified and districts like Assam remained separate.

Myanmar falls to Japan

Myanmar, known then as Burma, was also a province of the British Empire at the time and in 1937, and was separated from India as its own colony. According to "Bengal Partition Stories," there were many Indian laborers and workers in Myanmar and "a sizable population" was from Bengal. And when Japan started bombing Rangoon in December 1941 as part of their offensive against Great Britain during WWII, hundreds of thousands of Indian people left Myanmar.

While the exact number of evacuees is unknown, it's estimated that up to 500,000 Indian people left Myanmar and out of those, anywhere between 10,000 and 50,000 died along the way on the way to Bengal and Assam. And with robberies along the way, many who managed to survive made it back to India "with very little means."

In Understanding the Bengal Famine, Arundhati Choudhuri writes that with the fall of Myanmar to Japan, India lost "1.5 million tons of rice that fed the population of [Kochi], Travancore, Malabar and the industrial population of Madras and Bengal." The Allied retreat from Myanmar also meant that the army reserves were moved to Bengal and Assam and as the war industry also brought workers into Bengal, this put an even more increased strain on the food reserves of Bengal.

The boat denial policy

After Myanmar fell to occupation by the Japanese imperial army, Winston Churchill and the British instituted two scorched earth policies that would severely affect the food security of Bengal. One of them was known as the "boat denial" policy. According to Understanding the Bengal Famine, the boat denial policy was initially meant to apply to all of the coastal territories, but it ended up being limited only to coastal Bengal.

The boat denial policy entailed the destruction of boats, the evacuation of numerous villages, and the restriction of movement for boats that didn't get destroyed. Many communities lost their ability for transportation and fishing and "the policy actually destroyed the livelihood of many thousands." And as a result, when some regions had a surplus of rice crop at the end of 1942, it was incredibly difficult to move it to the regions where people were suffering from food insecurity.

When asked by the Famine Inquiry Commission of 1944 if the boat denial policy was responsible for killing local economies, Leonard George Pinnell, who implemented the policy, said, "I do not think a consideration of that sort would have been of any weight at all," per "Churchill's Secret War."

The rice denial policy

The second scorched earth policy instituted by Churchill and the British was known as the "rice denial" policy, which called for rice to be purchased from the districts under boat denial to be stocked up in the North and Northwestern parts of Bengal. Cultivators were told by Government purchasing agents that if they didn't comply with this policy, their grain would be confiscated or eventually robbed by the Japanese. Although enough rice for the region to eat was meant to be left in the districts, "actually far less was left," according to Understanding the Bengal Famine.

Not all of the rice actually made its way to the northern parts of Bengal. "Churchill's Secret War" records that in February 1942, civil servant Asok Mitra discovered that riverside storehouses that should have contained thousands of tons of rice held less than 10 tons. Meanwhile, there were numerous reports of rice being thrown into the river and being set on fire by soldiers.

In April 1942, governor of Bengal Sir John Herbert reportedly ordered the removal of rice from three districts within 24 hours. And because the government didn't have the administrative resources to enforce this endeavor, 2 million rupees were advanced to Mirza Ahmad Ispahani. Before long, the Ispahani Company became the "principal buying agent" of the government and had the power to seize the rice if need be.

Forced inflation

Another condition that led to the Bengal Famine was the wartime inflation that the British Empire caused in India. Understanding the Bengal Famine explains that in the wake of the Second World War, Britain outsourced the financing of the South Asian theatre of the war to India. From 1941 to 1946, the total government spending totaled nearly 38 billion rupees ($511 million) compared to the pre-war annual budget of $26 million.

Although Britain claimed that they would repay $235 million in sterling, they would only do so after the war even though they balanced the budget as though they'd already paid it. "These fictitious sterling reserves proved to be inflationary since it counted as reserves, against which money to the extent of 2.5 times [its worth] could be printed."

Rice prices soon went up and within 18 months they had quadrupled. Although this price increase wasn't limited to Bengal, according to "Poverty and Famines," the price increase was "much more acute" in Bengal than other regions. And when the Japanese army started bombing Kolkata in December 1942, Counterfire writes that wealthy individuals fled to the countryside, "where their increased purchasing power would contribute to food price inflation."

Panic buying and hoarding

With signs of a growing famine becoming more and more visible from the beginning of 1942 to March 1943, some started panic buying and hoarding rice. "Poverty and Famine" explains that "hoarding was financially profitable" and was also ultimately "encouraged by administrative chaos." As people stocked up on more food than they needed, food prices went up as its availability on the market decreased. Meanwhile, the British merely launched "a strong reassuring campaign to discourage hoarding," according to "Political Routes to Starvation."

In 1943, a conference was hosted in Delhi on the food crisis and one delegate claimed "the only reason why people are starving in Bengal is that there is hoarding." But although the government was ready to blame individuals for hoarding, the most detrimental hoarding was done by major corporations and the government. And much of what they hoarded went to waste. Counterfire writes that in 1944, rotten rice was given to industrial workers in Kolkata, and since rice can be stored without going bad for a year, this meant that the rice was just sitting there while millions starved to death.

Al Jazeera also notes that Churchill deliberately ordered food to be diverted to British soldiers "and to even top up European stockpiles."

A horrific death toll

The Bengal Famine of 1943 wasn't limited to a single year. 1942 set the economic stage for the famine and as starvation began in early 1943, the death rate peaked from "November 1943 through most of 1944," according to "Poverty and Famine." Some reports even claim that starvation lasted well into 1945.

It's estimated that the famine killed between two to three million people in 1943 in Bengal alone, if not more. Towns were filled with starving people and countless died in the streets of Kolkata, with over 3,000 bodies removed in October alone. Although the famine was a largely rural phenomena, Kolkata was also affected due to the masses of people coming to the city in search of food who died in the streets, according to "Resources, Values, and Development." Many weren't even begging for rice itself, but were asking for fanna, or phyan, the wastewater leftover after making rice, per BBC.

And while there were certainly factors working against the overall supply of rice, including a cyclone that affected a rice harvest, the famine didn't arise simply because there wasn't enough food for the population. It occurred because financially insecure people in rural populations were unable to access the food. Technically, the food grain supply was 11% higher in 1943 than in 1941, and yet there was "nothing remotely like a famine" in the year with overall less food grains.

What happened to the bodies?

While most bodies were burned in bigger towns, outside of the cities "bodies lay [where] they had fallen, rotted in the sun, or were torn apart by wild animals." According to "Hungry Bengal," in places like Kolkata, bodies were collected from the streets and burned after being categorized. And while extensive records about famine victims are incredibly few, due to the fact that famine affected some of the most marginalized people in rural society, it's known that the dead bodies were classified based on religious affiliation into one of two categories: Hindu or Muslim. It's unclear how authorities made this classification, but Mukherjee writes that it can be seen as "an extension of the simplistic binary which [the state was] want to categorize the population of India more generally." And because most bodies had their clothing taken because of the simultaneous cloth famine, there wasn't much left to make a religious assumption off of.

In Chittaprosad Bhattacharya's 1943 travel report "Hungry Bengal" (via So Many Hungers) written as he traveled through the Midnapur district, Bhattacharya questioned why "bodies that yesterday fought for our freedom and today are being literally eaten by dogs and vultures. Is this the tribute a nation pays to its fighters?"

After the famine subsided, Bengal's mortality rates remained high for years as malnutrition led to epidemics of cholera, small-pox, and malaria, according to "Modern India."

The British response

The British colonial government failed to recognize the famine until as late as October 1943, "once its eruption on the streets of Calcutta could no longer be ignored," according to "Hungry Bengal." Unfortunately, the response was ultimately more towards getting rid of the appearance of famine rather than actually addressing the fact that millions were starving to death. According to Counterfire, it was believed that the sight of people dying in the streets of Kolkata wouldn't be good for the army's morale. Chittaprosad Bhattacharya's book was also banned by the British government and "thousands of copies were destroyed," according to The Telegraph.

It's estimated that there were at least 100,000 people starving to death in Kolkata in October 1943, according to "Poverty and Famine." By the end of the month, the Bengal Vagrancy Act, 1943 was passed, also known as the Bengal Destitute Persons (Repatriation and Relief) Ordinance, and so those out on the street who had yet to starve to death were taken to camps.

By December 1943, the Secretary of State for India claimed that the "sick destitutes" had all been taken care of, but in fact they were taken to camps where they continued to starve. One medical observer reportedly claimed that people were being starved "to extinction" at the camps.

A cloth crisis

Coinciding with the Bengal famine was a cloth crisis due to the rationing and export of clothing. Much of the clothing produced was sent to British troops, to the point where Indivar Kamtekar suggested in his essay "State and Class in India" (via the University of Michigan) that "India clothed the armies east of Suez." And as the prices of rice had skyrocketed, so would the price of clothing as well, rising to "an abnormal extent" by the winter of 1942.

The scarcity of cloth left millions naked, and hundreds of thousands also ended up without shelter. According to "The Cambridge World History of Food, Vol 2," over 250,000 households in Bengal sold all of their land in 1943. "Considering the importance of land, such sales are a sign of desperation." As a result, many of the deaths were due to the weather because people had no clothing and no shelter of any kind. Kolkata's death toll in January 1944 was almost double its average from the previous five years.

The cloth famine didn't go unnoticed by the British empire. When Governor of Bengal Richard Casey visited New Delhi in June 1945, he brought up "the nakedness of Bengal due to shortage of cloth," according to "The Viceroy's Journal." On the rare occasion when cloth was sent over, it was reported to be "so moth-eaten or so rotten that it cannot stand the slightest strain."

Was there any aid?

Military aid to the region began in November 1943 and although the crisis was deemed "probably over" within a month by the Food Member of the Government of India, the effects of the famine lingered "well into 1946." According to The Economic Times, the British government never formally declared a state of famine and humanitarian aid was virtually "ineffective through the worst months of the food crisis." And while the government also tried to influence the rice prices, this led to black markets and sellers withholding stocks.

Although the Indian national press reported the famine vividly, the Bengal famine received little attention in Britain. Instead, British media focused on the food shortages in occupied Europe, according to "A Cultural History of Famine." But the lack of media attention didn't mean that it was necessarily ignored entirely. Bengal became "the first site of nutritional experimentation" with the use of intravenous administration of protein hydrolysates for emergency feedings in 1944. Although it was a "spectacular failure," it was used again in Holland during the 1944-45 Hunger Winter, "where it also failed."

Even when food supplies were finally able to reach Bengal, some people were already so emaciated that they required extensive medical treatment before they could "assimilate solid food."

Have there been famines in India since?

The British Empire claimed that through colonization they saved India from "timeless hunger," but the British seemed to be more adept at exacerbating famines than alleviating them. In 1878, the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society reported that in 120 years of British rule there had been 31 serious famines recorded in India. Meanwhile, in the preceding two millennia before British rule there were only 17 recorded famines (via So Many Hungers).

Other researchers have distinguished 12 major famines that occurred during British rule in India. And while many of these famines were affected by droughts and crop failures, it's notable that "no major famines have occurred since Indian independence in 1947," according to the Geophysical Research Letters. And while it's easy to lay the blame on nature, not all of the famines during India's history under British rule were affected by drought, including the Bengal famine of 1943.

While this isn't to say that malnourishment and undernourishment don't remain problems in communities in the region, famines depend on the distribution of food. "Famines are easy to prevent, [with] the distribution of a comparatively small amount of free food, or the offering of some public employment at comparatively modest wages," writes The Guardian.