The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Evel Knievel

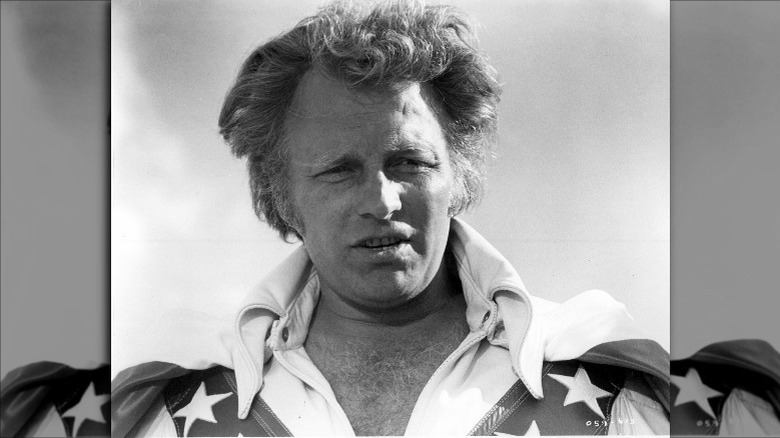

A self-described mix of "an Elvis Presley and a Liberace ... on a motorcycle," Evel Knievel's death-defying stunts brought a level of fame reserved for rock stars in the 1970s. With his signature, star-spangled leather jumpsuits, devil-may-care attitude, and unmistakable swagger, Knievel thrilled millions worldwide and became the role model for a generation of kids who crashed their bikes and skinned their knees on homemade ramps and suburban streets across America.

At the peak of Knievel's popularity, his incredible motorcycle jumps over cars, buses, and even sharks earned him a lavish lifestyle replete with sports cars, jewels, and his own private jet. The "last gladiator in the new Rome," Knievel packed venues. Evel Knievel toys flew off the shelves. Still, the world-famous daredevil continued to push his skills and his body to the limit with bigger stunts and higher stakes, and he paid the price in blood and broken bones.

Yet, by the decade's close, Knievel would find himself on the pop culture scrap heap. Like the fallen hero of a modern-day Greek tragedy, Knievel, king of the stuntmen, was brought low by the same hubris that had driven him from copper mines of Butte, Montana, to the top of the world. Despite the shattered relationships, a shattered reputation, and his shattered body, Knievel soldiered on through the following decades with no regrets. For 69 years, Evel Knievel lived life on his own terms and faced the consequences head-on. From triumph to tragedy, this is his story.

Evel Knievel was abandoned by his parents

As documented by Biography, Evel Knievel was born Robert Craig Knievel on October 17, 1938, in Butte, Montana. A hub for copper mining, Butte in the early 20th century more closely resembled a Wild West boom town than a modern, industrial city.

Evel Knievel's parents, Robert Knievel and Ann Knievel (née Keough), married young. Evel, called "Bob" by his family, was the first of their two sons. Brother Nic came less than a year later. As detailed in biographer Leigh Montville's "Evel: The High-Flying Life of Evel Knievel," Evel's dad, just 21 years old, wasn't cut out to be a father again or, for that matter, a husband to 17-year-old Ann. The son of Butte tire salesman Ignatius "Iggy" Knievel, Robert had a reputation as a philanderer with little regard for responsibility. While pregnant with Nic, Ann decided she had enough. After delivering a second son, she filed for divorce.

Free at last, Robert Knievel took off for California where he worked as a bus driver and raced cars. Ann dropped both sons off with Bob Knievel's parents and took off for Reno, Nevada. Now in their late 40s, Iggy Knievel and his wife Emma were faced with raising young children once again. The elder Knievels, especially Ignatius, were hardly up to the job. Suffering from what would later be defined as bipolar disorder, Ignatius would go for months without speaking. Emma, an intelligent woman who loved books, was not equipped for life with two rambunctious boys.

High school troublemaker

Life in hard-scrabble Butte held few opportunities for a restless Bob Knievel. A poor student but a skilled athlete who excelled at track and field and hockey, Knievel, as described in author Stuart Barker's "Life of Evel," wasn't a bad kid, but his endless energy, love of danger, and a penchant for mischief kept him in trouble for most of his adolescence.

As detailed in Leigh Montville's "Evel," Knievel was a teenage con man and a wicked prankster. In one of his most dangerous high school exploits, Knievel convinced several of his classmates to give him their belts which he used to tie the school library's doors shut. He then placed two large wastebaskets in front of the bound doors and lit their contents on fire. His target was the school librarian, who, for reasons unknown, had become his sworn enemy. Fire trucks were called to the scene, and Knievel faced stiff punishment. Still, the consequences were worth it for the thrills.

When Knievel was 16, his father returned to Butte. However, if his intention was to be a paternal influence, he was already too late. Kids grew up fast in a town like Butte where, according to Montville, the driving age was "whenever your feet could reach the pedals." Teenage Bob Knievel was on his own. After his junior year, Knievel either dropped out or was expelled from Butte High School. With no other prospects, Knievel headed for an uncertain future in the copper mines.

Aimless Knievel

With his high school education cut short, Bobby Knievel, like so many other young men in Butte, went to work for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. The work was grueling and dangerous. A mile below the earth, Knievel faced a myriad of occupational hazards ranging from mine collapses and fires to exposure to poisonous gases and lung disease. Among the jobs Knievel held at Anaconda were contract miner, skip tender, and diamond driller. "I did every job in the mine from the top to the bottom," Knievel told the author of "Life of Evel," Stuart Barker, "and I remember my first check — $57 for a week's work."

Meanwhile, Knievel's father had returned from California and opened a Volkswagen dealership with grandfather Ignatius. Still holding the grudge of his father's abandonment, Knievel pridefully rejected an offer to go work on the VW lot. Knievel escaped the mines when he secured a bus driving position for Anaconda. Tasked with ferrying his co-workers to and from the mines, Knievel couldn't resist taking a few risks on the road to frighten his passengers. Soon, many of Knievel's colleagues refused to ride with him. According to legend, Knievel lost his job with the mining company when he attempted a wheelie with a payloader. The vehicle came down on a power cable, leaving most of Butte in darkness.

Out of work and fearing the draft, Knievel joined the Army Reserve. However, the young daredevil's rebellious spirit made him a poor fit for military service.

Crooked Knievel

After leaving the copper mine, Bobby Knievel bounced from job to job. All the while, he indulged in death-defying antics and ran simple cons to alleviate his boredom and make a few dollars. As detailed in "Evel," Knievel began drawing crowds with his motorcycle early on. Patrons at a Butte A&W restaurant gathered to watch him attempt to climb a steep hill behind the eatery. Knievel's stunts drew a crowd, and in return, the manager gave him free food.

He was also getting by in less savory ways. An arrest for stealing a motorcycle landed him in jail, where some claim he picked up the moniker "Evel Knievel" when a cop jokingly compared him to inept local criminal William C. Knofel, known around the station as "Awful Knofel."

Ever the thrill-seeker, young Evel Knievel graduated from stealing bikes to cracking safes. Yet, fear of doing serious time in prison was too much even for Knievel. "I had so much pressure on me. I was scared to death I'd go to the penitentiary," Knievel told the producers of the 2005 documentary "Absolute Evel." "I said to myself when I looked in the mirror, 'What ... is the matter with you? Can't you live like a real person in society and amount to something in life?' I remember throwing the burglar tools and some dynamite into the Sacramento River and just telling myself I would never wrong another human being as long as I lived."

Evel Knievel's disastrous semi-pro hockey career

While in his youth, Bobby Knievel quenched his thirst for action in a number of ways outside of crime. A skilled skier, Knievel made some of his first daring jumps on the slopes. He had other athletic outlets, as well. While in the Army, Knievel took up pole-vaulting with some success.

As documented in the biography "Evel," at 19, the ambitious Knievel made a bid at starting a semi-pro hockey team in his hometown of Butte, Montana. Knievel became the owner, coach, and starting center of the Butte Bombers. With a small amount of seed cash from his father and grandfather and a line of credit from a local sporting goods store for uniforms and gear, Knievel managed to attract a number of players to whom he offered $50 per game. The Bombers rarely saw any of the promised pay but stuck with the team out of a love for the sport.

The Butte Bombers' one moment of glory nearly ended in an international incident. In 1960, Knievel managed to set up an exhibition game with the Czechoslovakian Olympic hockey team. The Bombers lost. However, Knievel literally made out like a bandit. The future king of the stuntmen did some impromptu fundraising between periods, allegedly to help pay for the Czech team's expenses. Mysteriously, the Czech team's money and the gate receipts disappeared, and the U.S. Olympic Committee was forced to foot the bill. The Butte Bombers folded soon after, and Knievel left hockey behind.

Worldwide fame came at a price

According to "Evel," shortly after retiring from a life of crime, Knievel took a job as an insurance salesman, but he soon discovered his greatest talent was selling himself. Knievel left insurance to sell motorcycles in Washington state. His promotions, which included motorcycle jumps over rattlesnakes and mountain lions, made him a local legend. In 1966, Knievel formed a troupe of stunt riders called "Evel Knievel and his Motorcycle Daredevils." Strictly small time, the crew quickly disbanded, and Knievel went solo.

As detailed in "Absolute Evel," in 1967, Evel Knievel got his first taste of fame when he successfully jumped 15 cars on ABC's Wide World of Sports. Still, Knievel wanted more.

While visiting Los Vegas, Knievel became enthralled with jumping the fountains at Caesars Palace. He hounded Jay Sarno, the hotel's owner, with hoax phone calls posing as journalists looking for details about some motorcycle stuntman who was going to jump the hotel's fountains. Sarno, fooled by the ruse and seeing dollar signs, brought Knievel in to set up the event. On New Year's Eve, 1967, Knievel made the jump. He cleared the fountains but came down short of the ramp's edge. The stunned crowd watched as Knievel's body limply cartwheeled and skidded across the pavement. In the failed stunt, Knievel suffered a crushed pelvis, a broken hip, a broken nose, a fractured jaw, broken ribs and head injuries that left him in a coma for weeks. Miraculously, Knievel recovered. When he regained consciousness, he was a worldwide superstar.

Evel Knievel versus the Hells Angels

As seen in the documentary "Absolute Evel," Evel Knievel often prefaced his stunts with inspirational messages and admonishments against the evils of narcotics. He also took a vehement stand against the so-called outlaw bike clubs whose blatant criminal activity had tarnished the public image of law-abiding motorcycle enthusiasts. To separate himself from the outlaw riders, Knievel publicly stated he wore white leather, not black, to distance himself from the dark side of motorcycling and specifically to draw a line between himself and the Hells Angels.

As detailed in the biography "Evel," Knievel's feud with the Hells Angels came to a head on the evening of January 23, 1970, at San Francisco's Cow Palace. Knievel was slated to jump 11 cars — an indoor record — when the announcer made the offhand comment that if the daredevil made the jump, he would "set the Hells Angels back 100 years."

A Hells Angel in the crowd threw a tire iron at Knievel while he was making his practice run. Later, Knievel spotted the Angel and carried out his mechanized retribution. "I rode this motorcycle at this guy and threw it down on that slick surface ..." he told the producers of "Absolute Evel." "I slid it right into him and knocked him a** over teakettle." The Angels descended on Knievel in a flurry of fists and feet. Much of the crowd came to Knievel's aid as the defeated Hells Angels fled, licking their wounds.

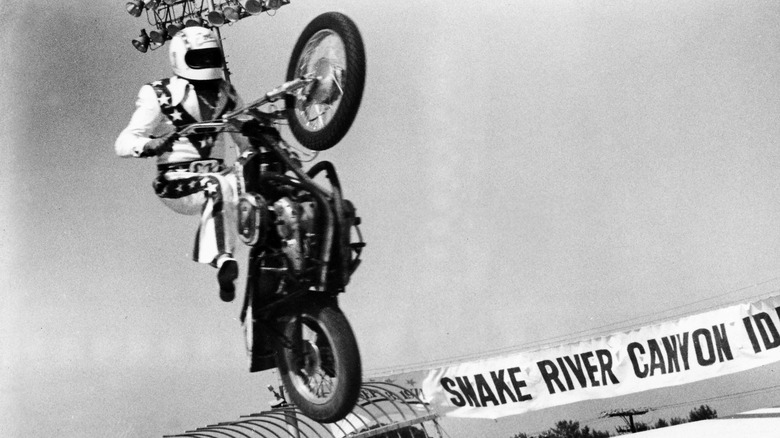

Snake River was nearly the end of the line

Evel Knievel had been talking about jumping the Grand Canyon long before the ill-fated Caesars Palace fountain jump that propelled him to fame. As detailed in "Life of Evel," the idea came to Knievel during a night of heavy drinking in 1966. When a friend jokingly suggested he try jumping the Arizona landmark, Knievel took the jest as a challenge.

Knievel managed to get permission to jump the Grand Canyon from the Department of the Interior and tentatively scheduled the stunt for July 4, 1968. However, the agency withdrew its consent when they realized the famed stuntman was serious.

Undaunted, Knievel "set his sights" on Idaho's Snake River Canyon. In 1974, he would attempt to traverse the one mile chasm in a specially constructed, steam-powered vehicle named the Sky Cycle X-2. As detailed in the 1998 documentary, "Evel Knievel: The True Story," the usually fearless Knievel was fatalistic about his odds of surviving the stunt. "He told us he wasn't going to make it. He really thought that," Knievel's daughter Tracey said. "He had set up everything at home ... so we knew he wasn't going to be there."

Although the Sky Cycle didn't make it to the other side because of a malfunctioning parachute, Knievel cheated death once again at Snake River. Still, the perceived failure of his grandest stunt would mark the beginning of a career downturn for the king of the stuntmen.

Tarnished hero

Although Evel Knievel liked to present himself as a tough-talking but clean-living role model, the truth of his private life was a far cry from his self-constructed public image. The ugly truth of Knievel's life behind the scenes was laid bare in 1977 with the publication of Sheldon Saltman's tell-all book "Evel Knievel on Tour."

As detailed in "Life of Evel," Saltman, a sports promoter, got an insider's view of life on the road with the famed daredevil while working with Knievel on the 1974 Snake River Canyon jump (and the 62-city tour designed to hype the event). Saltman witnessed first hand Knievel's womanizing, heavy drinking, out-of-control ego, fiery temper, and, most disturbingly, his abusive behavior toward his wife Linda.

According to "Evel," the publication of Saltman's unflattering portrait sent Knievel into a rage. He tracked Saltman down and viciously beat the promoter unconscious with an aluminum baseball bat, severely shattering his arm in the process. The assault landed Knievel in the Los Angeles County Jail and cost him his career. As reported by BBC, Saltman was awarded $12.6 million in damages, of which Knievel never paid a dime.

Marital strife

Evel Knievel married 17-year-old Linda Bork in 1959. Together, Linda and Evel had four children: two sons, Kelly and Robbie, and two daughters, Tracey and Alicia. The couple was married for 38 years, but their long union was anything but blissful. As detailed in "Evel," Knievel's archaic attitude toward marriage and family life coupled with his unbridled ego made Linda a second-class citizen in her own home. "He beat his wife. That was not romance. Everyone in town knew it," a neighbor of the Knievels from Butte told biographer Leigh Montville, "Linda is just the nicest person. Linda is class. Evel was not class." Yet, through her husband's infidelity and abuse, Linda Knievel stood by her man for nearly four decades. They divorced in 1997.

Knievel didn't stay a bachelor for long. Two years after his divorce, Knievel married Krystal Kennedy, a golfer from Florida, whom he had been seeing since 1992. Their marriage was short-lived, ending in 2001. As reported by the Associated Press (via Montana Standard), in 2002, Kennedy-Knievel, then 32, filed a restraining order against her 63-year-old ex-husband accusing him of hitting her and making threatening phone calls. In turn, Knievel accused Kennedy-Knievel of threatening him with a gun in a post-divorce dispute over jewelry. Amazingly, the couple reconciled and remained together until Knievel's death in 2007.

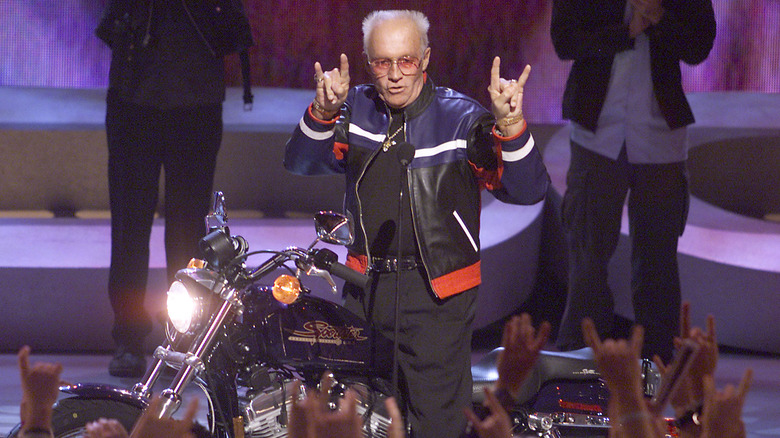

Sad decline of a '70s icon

Evel Knievel's life as the world's greatest daredevil took a devastating toll on his body. As of 2021, he holds the Guinness World Record for the most broken bones in a lifetime, 433, a record he set in 1975. By 2006, Knievel required an internal morphine pump to alleviate the near constant pain he suffered from fractured vertebrae (via "Life of Evel").

Along with broken bones Knievel suffered over the course of his career, his death-defying feats also had less obvious consequences. As documented in "Life of Evel," numerous unscreened blood transfusions received during surgeries in his heyday in the 1970s left Knievel with hepatitis C. The disease and years of hard drinking ravaged his liver. In 1999, Knievel beat the odds again when he received a life-saving liver transplant.

In 2004, Knievel was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a rare terminal disease that causes scarring and thickening of lung tissue. Doctors gave Knievel just three years to live.

The death of a daredevil

In his final interview, Evel Knievel waxed philosophically about his mortality. "All my life people have been waitin' around to watch me die," Knievel told Vanity Fair's Douglas Brinkley. "But I'm still here. I really think that there is a hereafter and this is just a testing ground ... I defied death. And I'm still doing it ..."

With his body ravaged by the effects of type II diabetes, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, alcoholism, and the after-effects of innumerable motorcycle crashes, Evel Knievel died at his Clearwater, Florida, home on November 30, 2007 at the age of 69 (via ESPN).

Knievel's body was returned to his hometown of Butte, Montana for burial (via Montana Standard). According to the New York Times, world famous televangelist Robert Shuller presided over Knievel's funeral, which was held at the Butte Civic Center. Friend and lifelong Evel Knievel fan Matthew McConaughey eulogized his childhood hero proclaiming "He's forever in flight now. He doesn't have to come back down" (via People).