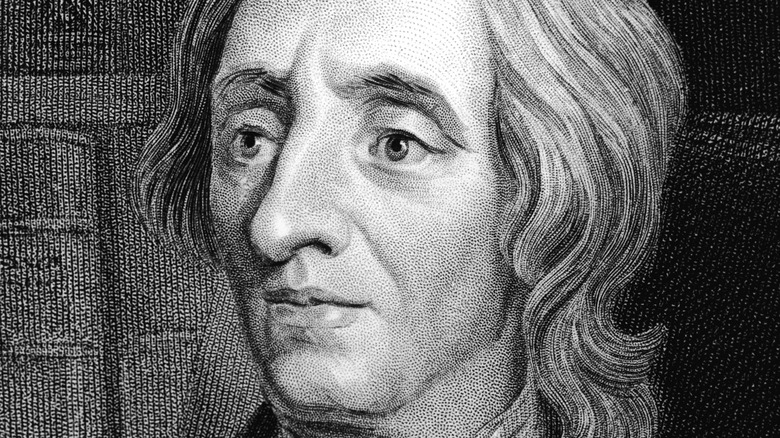

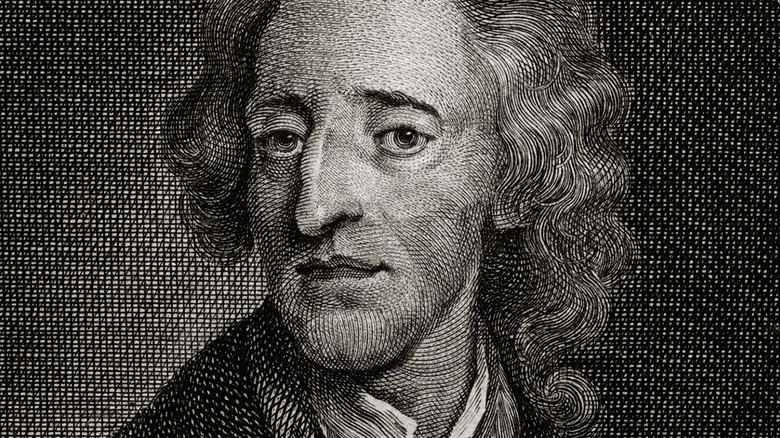

The Untold Truth Of John Locke

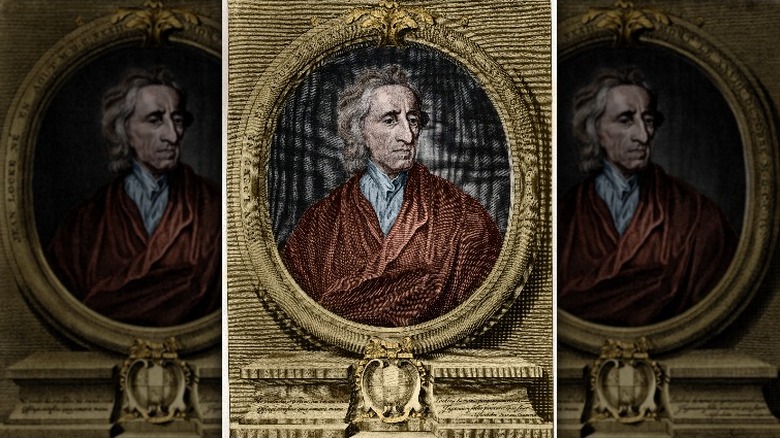

There are few intellectual figures in the history of Western thought as influential as the British philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). Dubbed the "father of liberalism," Locke was raised in one of the most tumultuous periods of English history, ravaged by civil war and characterized by religious differences and societal turmoil, all of which would come to inform his skeptical, reasoned, and above all tolerant world view.

Locke's writing is notable for spearheading many of the ideas that we in the 21st century hold to be self-evident: that all people are equal, and that all people deserve to enjoy personal freedom (per the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Against the backdrop of sovereign monarchy — which was being violently challenged in Locke's lifetime — such ideas were deemed exceptionally radical.

But how did John Locke emerge from an otherwise normal English background to formulate such groundbreaking ideas, and how did they become so ingrained in the Western psyche?

A childhood dominated by civil war

The ideas of great thinkers don't emerge in a vacuum; the circumstances of their personal lives and the societies in which they live shape their thoughts and dictate their way of looking at the world. So was the case with John Locke, whose formative years took place during one of the bloodiest and most tumultuous periods in the history of the British Isles: the English Civil War. Per Britannica, the conflict between King Charles I's monarchists and the roundheads representing the interests of the disenfranchised Parliamentarians began when Locke was just 10 years old, with the future philosopher seeing his father, a lawyer, enlist and serve in the conflict as a cavalry captain against Charles I.

The same source argues that it was through this conflict that Locke may have come to reject the notion of royal sovereignty — attained through the Divine Right of Kings — as it had typically been understood to that point. Certainly, the Civil War must have raised questions in Locke's young mind about politics, and about the invalidity of power for its own sake.

Though it must have undoubtedly traumatized Locke to see his father leave the household to participate in such a bloody war, the outcome was that, following the Parliamentarian victory, Locke Sr. was well placed to ensure his son received the best education that money could buy.

The trauma of corporal punishment

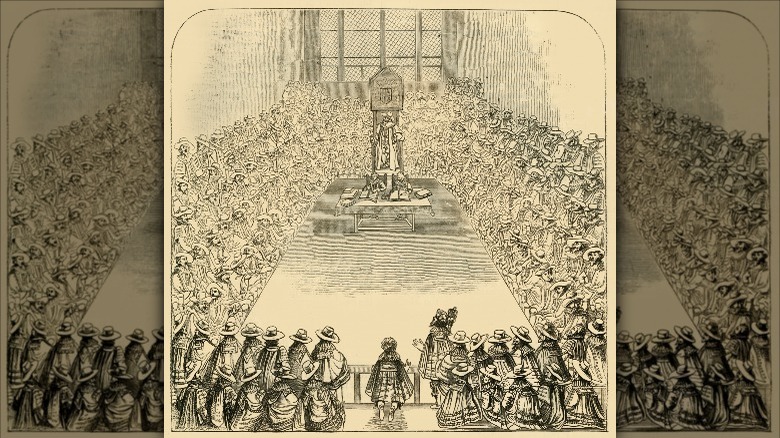

When John Locke was 15 his father secured him a place at Westminster School (pictured), a prestigious London institution (per Britannica). As a boarding school, it was to become Locke's home for many of his formative years. But although Locke was obviously a fine student — he was elected a King's Scholar in 1650, a title with a significant cash reward — his years at Westminster were not entirely happy ones.

Per the same source, Locke was tutored by the school's royalist headmaster, Richard Busby, who was notable for believing strongly in corporal punishment, especially the beating of students with a birch rod, a common practice at the time. According to teaching expert Robert McCole Wilson, not only was the birch unemployed to discipline disruptive pupils, but to test the fortitude of young men in the hope of "hardening" them to the needs of adult life (via Zona Pellucida). Though Locke agreed with contemporary English society that young men needed to develop the stereotypical "stiff upper lip," in his later writing Locke openly decried the free use of corporal punishment in education, stating: "I believe it will be found out, coeteris paribus, that those children who have been most chastised seldom make the best men."

A difficult education at Oxford

Despite the tough teaching practices of Westminster School, John Locke emerged as an exceptional scholar, who promptly secured a place for himself at Oxford, the finest university of the day.

At Oxford, Locke was treated to a classical education in logic, metaphysics, and classics, according to History, the standard education for students in the 17th century. However, according to the philosopher Wes Cecil, Locke was frustrated by what he considered the narrow curriculum afforded to the pupils of Oxford. It may sound extraordinary to us today, in a time when, typically, students focus on a single major subject at university that Locke should feel his induction into three subjects restraining (via YouTube).

But as Cecil explains, a classical education tended to focus on figures from antiquity, such as Plato and Aristotle. However, Locke, who was already well-read, was keen to explore the thought of his own age, particularly the writing of influential figures such as Francis Bacon. The future philosopher would study the classics in the day, and give himself a parallel autodidactic education by night, through which he would come to discover the prevailing trends of 17th century thought.

His first political tracts went unpublished

In 1660, the year the monarchy was restored in England (albeit in a radically new form), John Locke completed what Britannica describes as his "first substantial work." "Two Tracts on Government" can be characterized as a reaction to the political upheaval that had shaken England during Locke's life to that point, and is notable for its offering a considerably different view of authority than that proposed by his later writing for which he is better known.

According to the Journal of the History of Philosophy (via Project Muse), scholars have viewed the text as evidence that Locke was not a lifelong liberal, as some researchers had supposed. Rather, it has been argued that "Two Tracts on Government" reveals Locke had an authoritarian streak in his younger years and was a strident defender of law and order: "To be safe, as Locke saw the world, was to discover an authority that could override private men's judgement," per the same source. Such arguments run counter to much of what philosophers today consider the key tenets of Locke's principles.

Though "Two Tracts on Government" is now considered a landmark text in the development of Locke's political thought, it remained unpublished during his lifetime. Indeed, it was only finally published some 300 years after his death, in 1961.

John Locke's intimate relationship with the Earl of Shaftesbury

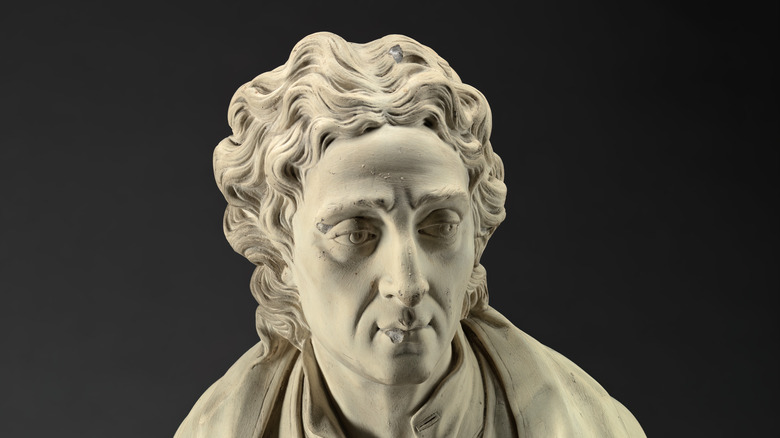

Alongside his classical education and deep political interests, John Locke also received extensive medical training during his many years as a scholar at Oxford. His natural intelligence and medical knowledge — even though he did not officially have a degree in medicine — brought him to the attention of Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper (pictured), an opposition political activist who would go on to inherit the title of the Earl of Shaftesbury, according to Britannica.

Shaftesbury convinced Locke to join his house and work with him as both a political secretary and personal physician, an agreement that heralded the start of a long and intimate friendship and political alliance that would shape the lives of both men. Their relationship would be sealed by Locke's overseeing impressively complicated abdominal surgery on Shaftesbury, in an operation that Britannica claims included the insertion of a "silver tube" directly into the Earl's liver, through which a painful tumor might be drained. Shaftesbury considered the operation a great success, and came to entrust Locke with responsibility with several more aspects of his life, both private and public.

Locke finally received a bachelor's degree in medicine in 1675, 17 years after receiving his master's in arts from the same institution (per the Online Library of Liberty).

John Locke profited from slavery

According to Britannica, John Locke further impressed the Earl of Shaftesbury by taking an instrumental role in finding a suitable wife for Shaftesbury's son, yet another success following his intervention into the Earl's chronic health complaint. Before long, Locke was entrusted with one of Shaftesbury's most grand projects: the establishment of a North American colony. Shaftesbury had been made one of the eight original Lord Proprietors of Carolina, where in turn the Earl had holdings and commercial interests (per Carolana). Shaftesbury employed Locke as secretary, in which capacity the philosopher composed with contributions from his patron "The Fundamental Constitutions for the Government of Carolina," in 1669, a document of guiding principles for the land that drew from the pair's shared liberal leanings and promised freedom of religion for its inhabitants — a reaction to the religious strife which had engulfed Britain during the young men's lifetimes.

But despite the respectable motives of such documents, many critics have pointed to the fact that, through helping to govern the lands in question, for all his liberalism Locke was guilty of colluding in slavery, which was practiced in Carolina at the time. Indeed, as Shaftesbury's right-hand man, Locke personally profited from it: in The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Race the academic William Uzgalis notes that Locke owned stock in numerous slave-trading companies.

The scholarly debate around Locke's attitude towards slavery itself is ongoing. Per the same source, biographers have claimed that Locke never truly made his ethical stance towards slavery clear, however, Uzgalis points out that Locke's writings on political power may be interpreted as his inherent belief that such slavery as he was involved in was indeed illegitimate.

Locke followed Shaftesbury into exile

John Locke's political thought grew through his association with the Earl of Shaftesbury thanks to the latter's strident political activism. As Biography notes, though Shaftesbury was an aristocrat, he was also one of the founding members of the liberal Whig party, the opposition who stood against the conservative Tories in the British Parliament.

According to Britannica, in 1975 Shaftesbury was given the post of Lord Chancellor of England, but a disagreement with King Charles II saw the Earl and, by extension, Locke fearing for their lives. As part of Shaftesbury's retinue, Locke traveled to France, where over the course of four years he would study the pre-eminent French philosophers and continue his studies into medicine. The same source notes that it was around this time that Locke began to form the material that would come to be published under the title "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding," (via Project Gutenberg) the philosopher's landmark work of 1689 which the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes as "one of the first great defenses of modern empiricism ... determining the limits of human understanding in respect to a wide spectrum of topics."

Locke returned to England in 1679, following Shaftesbury's arrest and imprisonment in the Tower of London. Upon his release, Shaftesbury and Locke continued to be vocal political agitators, and as such were accused of being involved in the so-called "Popish Plot" to assassinate King Charles II and replace him with his brother, James. Shaftesbury was tried for treason, but escaped punishment, and instead fled to Holland in 1681, where he would remain until his death two years later. In 1683, Locke also left England for Holland, where he would remain for six years. It was in Holland that Locke composed one of his most influential works: "Two Treatises Of Government," published in 1689 (per Britannica).

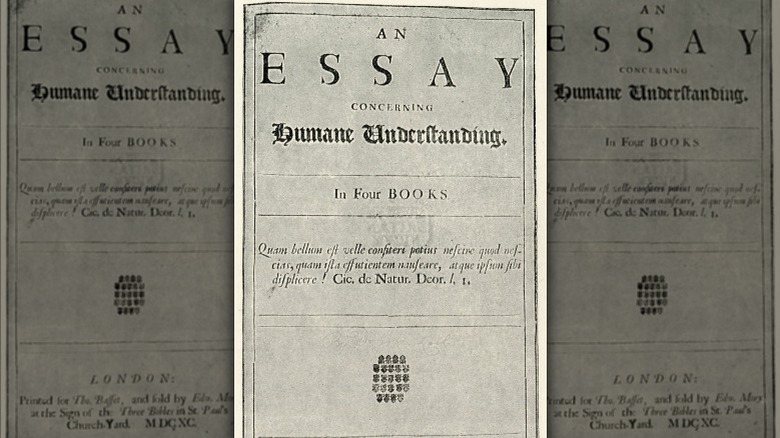

John Locke published his first major work at 54

John Locke's "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding," which was finally published anonymously in 1689, the same year as his "Two Treatises of Government." It was in this essay that Locke first laid out his influential ideas on how human knowledge worked, and the concept of empiricism.

Locke's essay on human understanding is typically considered his most important philosophical work (per Britannica), which lay the foundation for and greatly informed the formation of his subsequent political thought. As Philosophy Break notes, "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding" grows out of philosophical skepticism around the nature of knowledge which was typically addressed in the philosophy of Locke's day through rationalism, a school of thought primarily based on the writings of French thinker Rene Descartes.

Locke's work represented a decisive break with rationalism. According to Wes Cecil the essay was immediately recognized as a major contribution to Western thought and made Locke's name in the field of philosophy as a leading light in a new intellectual movement of "enlightenment thinking" (via YouTube).

Locke believed human understanding is limited

According to Philosophy Break, Locke's essay, which begins with the chapter titled "On Innate Ideas," argues against the prevailing ideas of the philosopher Rene Descartes, who claimed that human beings are born with a mind loaded with a set number of pre-existing ideas, or "innate principles." Locke claimed instead that each human being was in fact a "tabula rasa," or a 'blank slate,' which forms into a human mind through the reception of information via the senses, and through subsequent reflection on the world and the nature of the mind itself.

Some critics have been quick to reject Locke's theory of the tabula rasa by pointing to our modern understanding of genetics, and the current scientific consensus that information is passed along the generations, such as instinctive behaviors and habits. However, according to Wes Cecil, Locke's beliefs have been opposed on false grounds (via YouTube). Rather than a genetic theory, Locke was highlighting the lack of intrinsic human knowledge of religion, ethics, or political beliefs, and the fact that human beings form these ideas through empirical experience.

Locke believed in the power of disagreement

John Locke claimed in the introduction to his essay that his "present Purpose [was] to consider the discerning Faculties of a Man, as they are employ'd about the Objects, which they have to do with: and I shall imagine that I have not wholly misimploy'd my self in the Thoughts I shall have on this Occasion, if in this Historical, Plain Method, I can give any Account of the Ways, whereby our Understanding comes to attain those Notions of Things, and can set down any Measure of the Certainty of our Knowledge" (via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

But Locke's "plain" empirical method that certainties rarely exist, meaning that rather than establish and maintain set truths, multiple viewpoints ought to be encouraged and aired in an atmosphere of humble enquiry. According to the philosopher Wes Cecil, Locke eschewed the attempt to identify and engage with metaphysical ideas or absolute truth. Instead, Locke sought to identify "reasonable possibilities," presented by the evidence encountered through the senses and the synthetic comparison of various ideas (via YouTube). Locke wrote that any society or institution that forced the adoption of a single set of beliefs upon its subjects was totalitarian in nature, and that disagreement and debate were signs of a politically and intellectually healthy society.

John Locke's belief in God

Considering John Locke's grounded empiricism, perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of the philosopher's world view is his unshakeable belief in God. Indeed, in "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding," Locke claims that, despite the impossibility of providing the existence of providing His existence through our senses — as we would when engaging with the physical world — "we may more certainly know that there is a God, than that there is anything else [outside] us." In other words, we can be more sure of the existence of God than we can the things we actively experience; the only thing we can be surer of is our own existence as a thinking thing.

As explained in The Journal of Politics (via JSTOR), Locke argues that just as one can intuit that one's own mind exists, one can intuit the existence of God through the implicit understanding that something cannot arise out of nothing; that "bare nothing can no more produce any real being, than it can be equal to two right angles." Similarly, Locke also argues that consciousness cannot arise out of "senseless matter," and that therefore causation dictates that there must be an original intelligence that put thought into motion in the material world: God.

However, as Wes Cecil notes, Locke was also adamant that God could not act "irrationally," i.e., God doesn't act in ways that go against the natural laws he lay out to govern the material world (via YouTube). However, numerous academics have also pointed out inconsistencies in Locke's religious thought, particularly with regard to miracles, which he elsewhere claims are vital in establishing credibility for religious belief (via Springer Link).

Locke sought religious and political tolerance

In terms of how religion should exist in society, Dr Jan Garrett claims that Locke was a "latitudinarianist," a supporter of the "broad church" formulation of Christianity that encouraged religious tolerance (via Western Kentucky University). Locke believed that all those who believed in Jesus Christ's teaching about the nature of God deserved to practice their religion in whatever form that takes, either Protestant, Catholic or through any other denomination.

As Wes Cecil notes, Locke was a devout Christian who remained radically skeptical of religious dogmatic interpretations of the Bible (via YouTube). His empiricist philosophy informed his belief that human understanding is fundamentally unreliable — therefore, Locke believed that a single precise human interpretation of the word of God is likely to be flawed. Thus, toleration should be encouraged.

Locke similarly held a radically tolerant formulation of what constitutes good government. As Cecil explains, Locke was notable for positing that government should be deemed good as long as it is functional, and it fulfils the "social contract" with its citizens (via YouTube). As such, in Locke's view it is possible for good government to take many forms, from monarchy to parliamentary democracy.

John Locke and the Declaration of Independence

John Locke's idea of the social contract has remained one of his most influential and cited ideas. As the Independence Hall Association explains, Locke argued that a government is legitimate only through the consent of those it governs; that a government is loaned its power by the people. In response, the government in question has the task of employing natural law to protect the people and their rights. Such an idea may sound familiar today; the Independence Hall Association argues that Locke may be identified as the greatest influence on the Declaration of Independence, with the phrase "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" deriving from his "Second Treatise on Government," according to Constitution Facts.

According to Locke, the social contract dictates that if a government fails to live up to the expectations of the majority, then the people have a right to overthrow that government. In this way, Locke's thoughts may be considered to have directly motivated the War of Independence against British colonialism in America, and was thus decisive in shaping the events that led to the formation of the United States, as well as the wording of the document on which its government is based (per the Southern Methodist University).

The changing definition of liberalism

Since his death in 1704, John Locke has remained a vital figure in Western thought. But while he remains the "father of liberalism" among political historians, the word "liberalism" itself has come to take on new meanings over the years, and today is a term that has been adopted by groups with conflicting worldviews.

As noted by Britannica, one of the foundational tenets of modern liberalism is that government is a necessary institution through which society might best protect its citizens' right to individuality and individual freedom. The role of government, therefore, extends to protecting citizens from each other, but also from the overbearing control of the government itself — in other words, totalitarianism. In recent times, however, so-called "classical liberalism" has claimed that good government should therefore take a minimal hand in dictating the behavior of its citizens, as the government itself represents the greatest threat to personal freedom. Also termed "libertarianism," this concept conflicts with most formations of liberalism which typically defend the executive nature of the state, and its ability to aid its citizens in overcoming such societal problems as poverty and discrimination that might impact their individual freedom, per the same source.