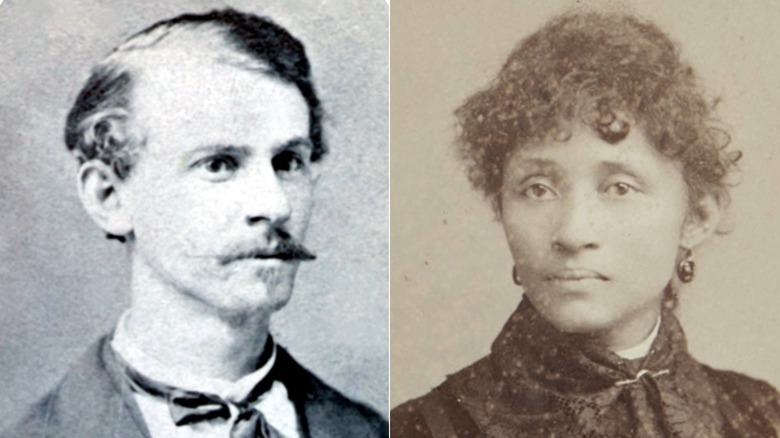

The Untold History Of Lucy And Albert Parsons

As far as power couples go, the 19th century would've been a drastically different time in the United States had it not been for Lucy and Albert Parsons. Though as anarchists, they were effectively an anti-power power couple. Unfortunately, their love was short-lived as an unjust judiciary system sentenced Albert to death. But after his execution, Lucy went on to maintain their legacy, facing police persecution and mistreatment even after her death.

Although the Chicago Tribune described Lucy as "wildly ludicrous," at one point, the publication redeemed her when they disparaged the behavior of the Chicago police, describing it as a "more real danger to the republic than either the mouthings or the acts of a handful of anarchists who may be considered revolutionary in their designs," per Chicago Reader.

In a letter to Lucy from his jail cell after receiving the guilty verdict, Albert wrote (per Counterpunch) that his "affection [for her] is everlasting" and makes one request of her: "Commit no rash act to yourself when I am gone, but take up the great cause of Socialism where I am compelled to lay it down." Needless to say, Lucy more than happily carried on the legacy she and her partner had started together. This is the untold history of Lucy and Albert Parsons.

Early life of Lucy and Albert Parsons

Lucy Parsons was born Lucia in 1851 in Virginia to an enslaved woman named Charlotte. According to Princeton University, Lucy's biological father was most likely Thomas J. Taliaferro — the man enslaving her and her mother. Throughout her life, Lucy gave varying answers about her ethnicity and "preferred that people speculate about her origins." When a reporter pressed for more information, Lucy reportedly stated, "I am not a candidate for office, and the public have no right to my past." And although Lucy claimed to have Black, Indigenous, and Latinx heritage, there are no records that indicate that she had Native or Latinx ancestry.

Albert Richard Parsons was born on June 20, 1848, in Montgomery, Alabama, and was descended from the Parsons family that landed in Narragansett Bay in 1632. According to his autobiography — written in 1886 after he was sentenced to death — Albert enlisted in the Confederate Army after his "young blood caught the infection" of war. Albert remained in the army for 18 months, joining Capt. Richard Parsons' Texas Cavalry Brigade afterward.

After the Civil War, both Lucy and Albert ended up in Waco, Texas. Lucy ended up briefly — though possibly not legally — married to Oliver Benton, a freed Black man 20 years older than her. Meanwhile, Albert became a Republican and attended Waco University for six months. Lucy also completed some schooling, and in the time before she met Albert, she had a child who died in infancy.

Anarchist organizers

In 1869, while working as a travel correspondent for Houston's "Daily Telegraph," Albert met Lucy Parsons as he traveled through Johnson County. After marrying in the fall of 1872, the pair decided to move to Chicago in 1873, per Albert's autobiography. There, living in a community of German-American immigrants, Lucy and Albert soon became involved in the labor movement.

After Albert was blacklisted from employment for his involvement in the wave of nationwide strikes of 1877, "affecting textiles, coal mining, and railroads," Lucy opened up a dress shop in order to make ends meet, Chicago Reader reports. Both Lucy and Albert joined the Knights of Labor and the Workingmen's Party of the United States, later known as the Socialist Labor Party. And while Lucy recruited women garment workers and housewives into the Working Women's Union (WWU), Albert became secretary of the Chicago Eight Hour League. They also started an anarchist newspaper known as "The Alarm," with Albert as editor and Lucy as contributing writer, per Illinois Library.

ThoughtCo writes that in the 1880s, Lucy and Albert left the Workingmen's Party and joined the International Working People's Association (IWPA), an anarchist organization. Disappointed with electoral politics and the two-party system, they both began advocating for capitalism to be overthrown by any means necessary.

Albert's execution

As part of the general strike to push for an 8-hour workday, Lucy and Albert Parsons led a march of thousands of workers through Chicago on May 1, 1886, in what Teen Vogue calls the very first May Day. But unfortunately, just a few days afterward, everything Lucy and Albert were working towards came under attack. Albert and several others, including August Spies, came together to speak at a rally against police brutality in Haymarket Square on May 4. And as the rally was winding down, a bomb went off. Even though neither Lucy nor Albert was still at the rally when the bomb went off — they left with the majority of the crowd as the weather began to turn — Albert would become one of eight people arrested and found guilty for the bombing in what became known as the Haymarket Affair (via Illinois Labor History). After Albert was sentenced, Lucy went on a seven-week speaking tour to raise money to appeal the case, experiencing "police harassment and occasional arrest," per "Lift Every Voice."

Later referred to as an "appalling miscarriage of justice" by the governor of Illinois John Peter Altgeld, the Haymarket affair resulted in the deaths of Albert Parsons, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, and August Spies. Although they were all found guilty of being involved with the bombing, the trial was considered a sham, and witnesses even testified that none of the accused were responsible for throwing the bomb, according to Thought Co.

Founding of the IWW

Lucy tried to see Albert Parsons before his execution with their two children, but instead, she was arrested, "taken to jail, forced to strip, and left naked with her children" until the hanging was over, Stanley Turkel writes in "Heroes of the American Reconstruction." After Albert's death, Lucy and her children lived in poverty, surviving with the $8 a week that was sent to them by the Pioneer Aid and Support Association.

But despite all the hardship she faced, Lucy maintained her commitment to the anarchist cause. In 1905, she and Mother Jones were the only two women among 200 men at the founding convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). According to the Zinn Education Project, she was also the only woman to speak at the convention. Throughout this time, Lucy also continued writing. In 1892, she started a paper known as "Freedom: A Revolutionary Communist-Anarchist Monthly," writes ThoughtCo, and in 1905 she also started editing "The Liberator," the paper published by the IWW. In "The Liberator," Lucy wrote a column about famous women and working-class history, in addition to advocating for "a woman's right to divorce, remarry, and have access to birth control," per "Heroes of the American Reconstruction."

A life of strikes and speeches

Lucy Parsons worked alongside the labor movement for the entirety of her life. She helped workers organize against unemployment and hunger and led protests and demonstrations that "brought together Chicago's Hull House and Jane Addams, the Socialist Party, and the American Federation of Labor" (via ThoughtCo). According to the IWW, in the 1930s, Lucy also worked with the coalition for International Labor Defense on the Scottsboro Eight and Angelo Herndon cases, which was one of the first times that her work dealt intimately with racism in the United States. But as time went on, even Lucy couldn't help but get discouraged, wondering, "Have things gotten better or worse since you and I, 50 years ago, began to watch the human procession," per the Chicago Reader.

Police targeted Lucy throughout her entire life and arrested her numerous times for public speaking, even though Judge Tuley ruled in 1889 that anarchists also have a right to free speech. At one point, Chicago police described her as being "more dangerous than a thousand rioters," per "Good Trouble" by Brian Wolf. At times, Lucy's ideas regarding freedom were limited compared to the freedom she proselytized. LA Review of Books writes that she was estranged from her son, Alfred Jr., and after he decided to join the Army, she had him committed to the Elgin Asylum, where he remained for 20 years until his death. She also quarreled with Emma Goldman regarding "Goldman's public advocacy for free love."

What happened to Lucy's library?

One of Lucy Parsons' last major public appearances was speaking to striking workers at International Harvester in February 1941. And in a twist of fate, International Harvester was the "successor to the company that had provoked the Haymarket events 55 years earlier," according to Workers World.

On March 7, 1942, Lucy died in a house fire after her woodstove caught fire and she became trapped in the burning house. IWW writes that her lover, George Markstall, also died the following day due to the wounds he sustained in an attempt to save her. But even in death, the police were prepared to deliver one final injustice. Chicago Reader writes that at the time of her death, Lucy had accumulated a massive library of letters, manuscripts, and between 1,500 and 3,000 books. Although they were badly damaged in the fire, when her executors came to retrieve them from the house, they discovered that the entire library was completely missing.

The police department's Red Squad claimed that the papers were handed over to the FBI, but as of 2021, no one knows for sure exactly what happened to Lucy's library. In 2016, Muckruck filed a request with the FBI to see what remained of Lucy's library, and although the bureau claimed that the records were sent to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), NARA was ultimately unable to find the documents.