Popular Food Fads From The 1800s

Food is so fundamental to our existence that it's no surprise humanity has spent tens of thousands of years obsessing over it. Prior to the invention of 7-11s and bags of chips, that obsession mainly focused on hunting and gathering enough of the stuff to ensure survival. But as civilization has crept in, our food obsessions have gone a little wonky, because we're biologically programmed to eat as much as we can when we have food (per Psychology Today)—and programmed to eat stuff that's actually unhealthy for us when we're not living short, terrified lives constantly fleeing apex predators (per Cleveland.com).

For folks who grew up with Instagram, food fads are nothing new. They fall into two basic categories: Diets and novelties. Fad diets tend to be extreme, totally removing certain foods or dietary components (like the way the Keto Diet treats carbs like the enemy), and novelty foods like the cronut or avocado toast dominate our social media until they either fade away or get absorbed into the mainstream.

But it's a mistake to think these are modern inventions. We've had dubious diets and buzzy snacks for centuries now, though things didn't really get going until the 19th century. To prove it, here's a rundown of some popular food fads from the 1800s.

Oysters

Everyone likes an oyster once in a while, but for most of us they're just one component of a nice seafood dinner, or an occasional treat. But in the 1800s, the United States was in the grip of what can only be called an oyster craze.

According to The MSU Campus Archaeology Program, the surge in popularity of oysters in the 19th century began when fishermen developed new technologies that allowed for the mass cultivation of oysters. These techniques did incredible damage to the environment but produced so many oysters the mollusks became a rarity: A prized delicacy that was incredibly cheap. As The New York Times notes, the only difference between how the rich and the poor enjoyed their oysters was how they washed them down: The rich drank champagne, the poor drank beer.

And as JSTOR Daily makes clear, the oyster craze was national, stretching from coast to coast. Oysters were sold from street carts, served in fancy restaurants, and consumed in a dizzying array of recipes that ranged from frying to pickling. The oyster craze soon led to a near-collapse of the oyster business as oysters were over-harvested while pollution eroded their breeding grounds. By the end of the 19th century the oyster craze had ended more or less by necessity—though The Los Angeles Times reports a final spurt of oyster madness came when a man named Al Levy invented the Oyster Cocktail, kicking off a final mini-fad.

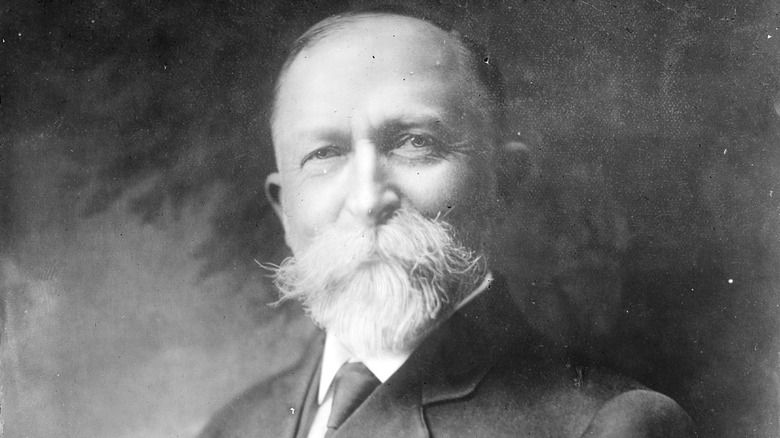

The Banting Diet

You might think that fad diets focused on lowering or eliminating carbohydrates from your diet are modern inventions, but one of the first to sweep the world kicked off in the 1860s when a retired undertaker decided he needed to lose weight.

As reported by Narratively, William Banting was a bit of a celebrity in 19th-century England. He was known for his elaborate royal funerals that were almost like stage shows. In 1863 he was retired in his 60s and unhappy with his weight—at five foot six, he weighed 202 pounds. According to The Guardian, Banting was suffering various physical maladies as a result of his weight—and was depressed at the mockery his girth earned him on the street. On the advice of a new doctor Banting tried a diet that deprecated carbs, starch, and sugar. Banting lost 46 pounds in a bit more than 12 months.

Banting was so excited by this progress he published an open letter to the public titled "A Letter on Corpulence." The pamphlet was an immediate bestseller, going through 50,000 copies in two years—and a diet craze was born. In fact, his name was transformed into a verb: People talked about how they were "banting" or planning "to bant" in order to lose weight. Banting himself lived to the ripe old age of 81, and never once regretted his extreme diet or the fad he inspired.

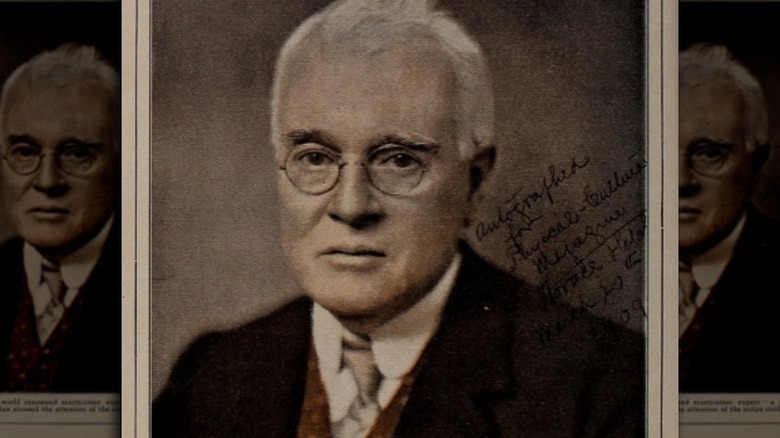

Fletcherism

Many of us were admonished as children to "chew your food." And chewing is certainly a major component of eating, although we've all also had the experience of being so intensely hungry that food seems to magically vanish inside of us without once touching our teeth. But one of the major fads of the late 19th and early 20th centuries involved chewing your food ... a lot.

According to PopSci, Horace Fletcher had some decent ideas about nutrition and eating. For example, he advised that you should only eat when you're hungry—a reasonable enough piece of advice. But the food fad he launched known as Fletcherism wasn't so reasonable: Fletcher advised that you should chew your food until it liquefied in your mouth and became fully mixed with your saliva so you could basically drink it. According to Slate, Fletcher often advised chewing a single bite of food more than 700 times before swallowing.

Fletcher was rich and had a lot of famous friends, and convinced folks like Henry James and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to give "Fletcherizing" a go. It soon became a bona-fide fad, which also led to a bit of a backlash from the poor folks who had to sit at the dinner table with Fletcherizers and watch them chew ... and chew ... and chew.

The Lord Byron vinegar rice diet

These days having a celebrity endorse a new diet plan is a pretty regular event. This is the age of the professional influencer, after all. But there have been celebrity influencers since there have been celebrities, and in the early 1800s one launched one of the unhealthiest fad diets of all time.

As noted by Radical Art Review, Lord Byron was one of the first modern-style celebrities. A talented poet, he was handsome, smart, and sexy. His poems sold like hotcakes, and the image of the brooding, rebellious "Byronic Hero" that he crafted made him into a superstar of his time. But like many celebrities, Lord Byron had a molten core of insecurity—according to BBC News he was deeply concerned about his "morbid propensity to fatten." As Vice reports, this was probably a case of body dysmorphia.

Lord Byron smoked cigars to suppress his appetite and crafted a bizarre diet that relied on drinking vinegar in large quantities, supposedly to stave off hunger. His adoring fans followed suit, in part to mimic his gaunt, pale look (the better to express his dramatic inner turmoil) and there was worry that an entire generation of young folks in Europe would end up on death's door from what was essentially a starvation diet.

Turtles

There's no other way to put this: It's absolutely shocking how many turtles people ate during the 1800s. It was an astounding number of turtles—so many, in fact, that NPR reports we almost wiped out the diamondback terrapin entirely. Smithsonian Magazine notes that the most popular way to serve up some delicious turtle is via turtle soup—although Saveur points out that many high-class dinners would offer up to three different turtle courses as standard. Some of those fancy dinners were literally known as "turtle frolics."

The turtle craze was so intense we nearly ate up all the turtles, and by the late 1800s and early 1900s turtle populations had declined so much it became an exorbitantly expensive dinner choice. According to Atlas Obscura, this was one reason Mock Turtle Soup was invented. As you might guess, it's not actually made from turtle—a calf's head was substituted. It was a much cheaper meal that approximated the flavor of the real thing, so if you had a hankering for terrapin but couldn't afford it, you had a backup plan.

Since most turtle soup recipes called for a surprisingly large amount of alcohol, Prohibition in the 1930s finally killed off turtle as a common dinner item in the United States. You can still find turtle on the menu in a few areas of the country if you go looking for it, but the craze is long past.

Beefsteak dinners

You may have heard the term "beefsteak dinner" and imagined it was a fancy affair with aged rib-eye and fine wines. You could not be further from the truth. As reported by Westchester Magazine, this peculiar fad came into being in New York in the 19th century. It was pretty bare bones: A group of men would gather in a pub or even a basement where they would feast on all-you-can-eat slices of beef, served on hunks of bread and doused with Worcester sauce and butter. The weirdest part was that no utensils or napkins were allowed.

According to Gothamist, these feasts were so messy the men usually strapped on aprons when they sat down to dinner. The Beefsteak Dinner was a place where men could talk freely and eat gluttonously—the whole point was the lack of etiquette or polite behavior. Over time it bubbled up to the fancier levels of society. The Museum of the City of New York Blog notes that Beefsteaks were often staged by business and fraternal organizations, making them important spots for local politicians and businessmen to make connections and network.

At the turn of the century, the male-only Beefsteak started to change to admit women, and the menu became more varied. As New York City's demographics changed in the middle of the 20th century, the Beefsteak Dinner slowly became an icon of a past age.

Tamales

Today we take the tamale for granted. These delicious concoctions of starchy dough and spicy fillings all wrapped in a warm corn husk can be found just about everywhere and in a dizzying array of varieties. But in the late 19th century the tamale was just being discovered by White America, and that discovery caused a sensation.

As reported by The Anchorage Daily News, the tamale craze launched in San Francisco in the 1880s, and for the next few decades spread steadily throughout the country. According to SF Weekly, in 1892 a man named Robert H. Putnam appropriated this Mesoamerican staple and created the California Chicken Tamale Co., which put street carts all over San Francisco selling hot tamales for ten cents each.

The tamale took off like a house on fire. In less than half a year Putnam had 500 employees and raised $10,000 in investor money (about $300,000 in today's money). Tamales became such a fad that Gastro Obscura reports there were violent tamale turf wars that saw competing vendors—dominated by poor immigrants from all over the world—scrapping over choice territories. One reason for this fierce competition was the opportunity that tamales offered immigrants. As noted by author Cynthia Clampitt in her book "Midwest Maize," selling tamales was a business that just about anyone could launch without any capital or other resources. The fad petered out by the 1910s as the novelty wore off—but luckily tamales were here to stay.

Celery

Today celery is ... just sort of there. Most of us regard celery as either a cocktail garnish or as a conveyance for more interesting food. But back in the 1800s here was a real fad for celery, which was regarded as an exotic and luxurious food. As noted by TASTE, the reason celery became so briefly popular is the same reason many things become fads: It was rare. Celery is difficult to grow, and thus it was expensive and difficult to find. Those two factors made it the ideal status symbol for wealthy Victorians. Quartz makes an important point as well: There are many different varieties of celery aside from the bright green version we're most familiar with, and that makes the 19th century fascination a little easier to understand.

Once the wealthy made celery a must-have food craze, the poor soon followed, although they could generally only afford to serve it on special occasions. The rich, never shy about bragging, invented the Celery Vase to display their celery as ostentatiously as possible, according to Gastro Obscura. So if you're ever staring at a celery stalk in your Bloody Mary and pondering its awfulness, remember that we once considered celery so cool we displayed it in our homes like art.

Celery's downfall was typical: Its popularity inspired folks to figure out how to grow it more easily and cheaply, and once everyone could have it, they realized they didn't actually want it.

Eels

If you've ever eaten eel, it was probably in a sushi restaurant, where the fish remains a staple and quite popular. Or possibly you had a traditional eel pie in London, where eels were once so easy to pull out of the Thames the fish became a popular food for the working class and remains popular today according to The New York Times.

While eel has been part of the global diet for centuries, back in the 1800s eels were briefly one of the most popular foods on the planet. Saveur reports that when the Pilgrims arrived in what would become Massachusetts in the 17th century, the local Wampanoag Indians saved them from starvation in part by teaching them how to catch and cook eels. According to Smithsonian Magazine, eels were once so popular that people actually used lobsters as bait to catch them. Aside from the fact that eels could be found just about everywhere, one reason the fish became so popular was the sheer variety of ways you can cook them—eels can be baked into pies, grilled, sauteed, steamed, or made in dozens of other ways.

As with many food fads, what killed off the eel was, literally, the way we killed off the eel: We loved the fish so much we almost drove it to extinction. By the 20th century eels had declined in popularity—but is still listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation.

Breakfast cereal

As noted by The Guardian, the idea that breakfast is the "most important meal of the day" is largely the invention of lobbyists and marketers. Before the late 1800s, people tended to eat whatever was around the morning, and this led to what we think of as the "farmer's breakfast," which was heavy on eggs (which the chickens would have laid by morning) and meat that could be slaughtered, cured, and stored—like pork sausage.

But as noted by History Things, this diet was high in meat and low in fiber, and led to a host of health problems that became worse as people transitioned from lives of hard manual labor to more sedentary lifestyles. As doctors began pushing the idea that getting more fiber into our diets was a good thing, a man named Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (yes, that Kellogg) almost accidentally invented cereal when some experimental wheat cereal was left overnight on a roller, causing it to flatten into crispy flakes. Boom! Breakfast cereal was born. It proved so popular that people began writing to him and asking him to ship some to them. It didn't take long for Kellogg to go into the cereal business.

Cereal quickly became a bona-fide fad, and our modern breakfast staple was born. According to PBS, the first commercial cereal was marketed in 1896, and by 1902 there were no fewer than 40 cereal brands competing for the market.

Graham Crackers

Graham Crackers are still an extremely popular food, in large part because they're a fundamental part of s'mores, the best reason to build a campfire. But their origins and the food fad that resulted are largely forgotten.

As reported by Reader's Digest, the Reverend Sylvester Graham believed strongly that sex was a terrible idea and everyone should stop doing it immediately if not sooner. He also believed that indulging any of your senses could lead to sexual urges, and so he proposed that everyone eat extremely bland food, and he invented the original Graham Cracker to help. In its original form, it was just an unsweetened square of baked dough that probably tasted like cardboard. Which was the intention.

According to The Atlantic, Graham and his bland, tasteless crackers (as well as his anti-sex moralizing) took the country by storm in the 1830s—people following his diet and eating his crackers actually called themselves Grahamites. In fact, Graham's brief surge of foodie celebrity is considered the beginning of the vegetarian movement in America. Decades after Graham's death, The Huffington Post reports that a commercial bakery called The National Biscuit Company began selling a version of the Graham Cracker—and rode the popularity of the snack to eventually become one of the largest food companies in the world, today known as Nabisco.

The Fruitlands Diet

The Fruitlands Diet was a short-lived fad that only took hold for a few months in the winter between 1843 and 1844. Which is good, because it was kind of a dangerous diet based more on crackpot ideas than any nutritional science. As reported by The Vintage News, the Fruitlands Diet takes its name from the Fruitlands farm owned by the Alcott family in Harvard, Massachusetts—where "Little Women" author Louisa May Alcott was born and largely raised. As explained by The New York Times, Louisa's father, Bronson Alcott, launched a communal living experiment on the farm in 1843. The idea was to live a life of New England transcendentalism. They avoided oppressing animals or their fellow humans, and so ate no meat, used no draft animals, and refused to use anything produced by slave labor (including cotton clothing).

There was also a very weird diet, which The Huffington Post notes was intended to purge people of their beast-like ways. The diet was entirely vegetarian, but with a weird twist: Only vegetables that grew up (towards heaven) could be eaten—anything that grew down into the ground, like potatoes, was no good.

The fad didn't last long: As noted by author Caryn Hannan in her book "Connecticut Biographical Dictionary," by the end of the winter in 1844 the Alcotts had been abandoned by most of their fellow Fruitlanders and were on the brink of starvation.