What We Know About The Earliest Christmas Celebrations

Wandering through a shopping mall and stocking up on presents for the annual Christmas party may seem specific to modern times, but even these apparently secular traditions have their roots in the very first Christmas celebrations – and beyond. The earliest Christmas celebrations date back to Ancient Rome. As described by historian Judith Flanders in "Christmas: A Biography" the way Ancient Romans celebrated the holiday was in many ways similar to modern festivities, but for early Christians Christmas feasts, parties, and even worship were a part of a complex blending of cultures and religions. While records from this time are scarce there are still stories of the feasts and festivals that Romans threw to honor their gods, Christian and "pagan" alike.

The concept of a December 25 holiday celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ and the way it would be celebrated were invented during these times. As detailed by Newsweek, interest in the idea of determining when Christ was born came hundreds of years after his death. Historians have multiple theories about why December 25 was selected by the early Church, but the most popular is probably the date's overlap with other extremely popular festivals of the day. Many of the customs that would become Christmas traditions came from older holidays, such as the raucous Saturnalia festival or solstice celebrations honoring the birth and rebirth of the sun.

This is what we know about the earliest Christmas celebrations, and where they came from.

Roman feasts and parties

The Roman Empire initially was a harsh place for early Christians. In A.D. 64, after the Great Fire of Rome, Emperor Nero had as many Christians as he could publicly executed. As explained by PBS, it took hundreds of years for Christianity to be accepted, but in 313, Emperor Constantine made Christianity legal. Within 10 years, Christianity was the official religion of the empire.

The earliest documented celebrations of Christmas (a newer holiday than Easter or Epiphany) took place in the Roman Empire. Though records from this period are scarce, it is likely that Romans celebrated Christmas similarly to their other feasts and festivals.

One major component of these festivities was eating ... a lot. As described by The Met, these banquets were a symbol of the host's wealth and status. The elite dined amidst extravagant decorations and live entertainment. Dining rooms were lavishly decorated with mosaics and sculptures. Guests ate lying down together on large and expensive couches. The meal itself would be many elaborate courses.

Group worship

The Christmas story – the story of the birth of Christ, sometimes called the Nativity – was often celebrated as part of the holiday Epiphany, held in early January. Although at one time Christians had been persecuted in Rome, by the late 300s it would have been highly controversial for powerful Romans not to celebrate this major Christian holiday.

Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that Emperor Julianus Augustus was a believer in soothsaying and "pagan gods," but he pretended to celebrate to keep the peace and make his people happy. Christians gathered in churches to pray together, so the emperor joined them in prayer.

The Nativity was celebrated on December 25 after the year A.D. 430. As described in "The Oxford History of Christian Worship," an overnight Christmas ceremony was performed at the basilica of Saint Mary Major, which displayed a relic believed to come from Jesus's crib. Gospels were read aloud, including the Gospel of Luke's account of the birth of Christ (which is still a very common reading at Christmas ceremonies today.)

The Christmas story is retold

Widespread belief in the Nativity reshaped Christians' beliefs around Christ being a human being. Mary, as the mother of God and a central figure in the Nativity story, gained importance. As both Christmas celebrations and their religious and cultural impact became more popular, the story of Jesus's birth captured the imagination of artists, writers, and poets. These works, many rendered anonymous by time, were highly influential, and continue to impact modern representations of Christmas.

As explained in Joseph P. Kelly's "The Birth of Christmas" about the first feasts celebrating the birth of Christ, new hymns and prayers were written specifically for Christmas celebrations and to tell the Nativity story. Christian scholars added details to the Nativity story, especially playing up the importance of the Magi and introducing visual descriptions of the star that led them to the birth. Visual artists depicted the story in frescos and sculpture.

Baptisms

By the fifth century, Christmas was one of the most important holidays for Christians (second only to Easter). For some churches of this period, one day was not enough to celebrate the birth of Christ, and an extended period of preparation and festivities became the ideal to bring people into their congregations through baptism.

Baptism was extremely symbolically important in Ancient Rome, and at one time, treasonous. As described by senior Research Professor of Biblical Theology Alan Streett, Roman emperors demanded "sacramentum" or a sacred oath of obedience from their soldiers. This was also referred to as "receiving the sacrament," a phrase now synonymous with Christian worship. Early Christians also referred to baptisms as "sacramentum," meaning that they were pledging their lives to the Christian God. Initially, this was viewed as highly subversive in the Roman Empire, since it implied loyalty to something other than the emperor.

As Christianity became the dominant faith, however, baptisms became common, especially when celebrating Christmas. As detailed in "The Birth of Christmas," when a December 25 Christmas became the standard, many churches that had been celebrating January 6 as the date of Christ's baptism adopted all the days in between as a time for baptizing new Christians into the faith.

Gift giving and indulging

Gift giving may be the most common way of celebrating a modern Christmas. The cultural norm of buying presents for the holidays has caused everyone from 17th century Puritans to modern American students to lament Christmas becoming so commercial. In actuality, the tradition of buying presents is almost as old as Christmas itself. The resentment of gift giving as a tradition is just as ancient.

Around the year 400, Bishop Asterius of Amasea (via Baylor University) wrote about how Christians were celebrating Christmas by buying each other presents. Like modern nay-sayers, he warned against the practice, stating that people were going into debt to buy Christmas gifts. He wasn't alone. Numerous bishops complained that revelers were eating too much and getting drunk while celebrating Christmas.

Some have connected the practice of giving presents with the story of the Magi giving gifts to the baby Jesus, but as stated in "Sociology of Gift Giving," buying Christmas presents and overindulging at Christmas feasts may have had less to do with the story of the Nativity, and more to do with the time of year. Christmas was far from the only celebration that took place in mid-winter.

Blending of faiths

In A.D. 336, December 25 was established as the day that Christ was born, and the date that Christmas celebrations would be held. As stated in Britannica, there are multiple possible explanations for the Church selecting this date. One of the most commonly accepted is that the date was deliberately chosen because it was one that most were already celebrating. Putting Christmas on December 25 caused it to overlap with several existing holidays, including the raucous Saturnalia and the solstice ceremony for Sol Invictus.

The traditional ways of celebrating all of these solstice and midwinter holidays mingled with early Christmas celebrations. While this cultural overlap certainly helped Christmas to become more popular throughout the Roman Empire, Christian authorities frequently complained about the more "pagan" ways of celebrating, like wearing masks, drinking, and partying. To make matters more complex, some early Christians continued to worship other gods and celebrate older holidays, even when they would seem to conflict with Christmas.

Saturnalia

As stated by History, Saturnalia festivities honored the Roman god Saturn with hedonism and disrupting the social order. Few holidays were so influential on future Christmas celebrations as Saturnalia. Held in December, the festival was the most joyous in the Ancient Roman world. Saturnalia celebrations involved feasting, visiting friends and family, and gift-giving. Homes were lit with many candles and decorated with greenery, including small trees.

Saturnalia was also notorious for debauchery and overindulgence. Revelers drank, gambled, and played pranks on each other. As described in "Christmas: A Candid History," Saturnalia was a time for inverting society's norms. Few had to work during the celebrations, and all people were supposed to be treated the same, even people who were enslaved. There were massive feasts during which every guest was supposed to have equal access to every course. The rich were encouraged to give banquets for their servants and wait tables themselves. A "Mock King" was selected from any walk of life, and they temporarily had all the authority of the emperor.

As described by Violet Alford's "The Hobby Horse and Other Animal Masks," animal masks were used to celebrate Saturnalia but continued to be beloved as Christian holidays became more standard, much to the irritation of early Christian priests.

Birth of Mithras

According to anthropologist James George Frazer (via The Washington Post), the birth of Mithras was also commonly referred to as a "nativity." In Egypt and Syria, a celebration referred to as "the ritual of the nativity" was held on December 25. Believers spent the night in indoor shrines. At midnight, they would shout, "The Virgin has brought forth! The light is waxing!"

During the third and fourth centuries the cult of Mithras became popular among Roman soldiers. As stated by Britannica, it was this religion that Emperor Julianus Augustus had secretly committed himself to when he pretended to celebrate Christmas. Mithraism was Christianity's main competition for followers, with some believers embracing both gods. The rivalry between the two faiths extended to their festivals – both of their chief deities were said to be born on December 25. Many believe that was not a coincidence.

Mithras was a god of light, worshipped in extreme secrecy in Ancient Rome – particularly among the military. While little is known about the cult of Mithras, some records of their festivities have remained. As stated in "The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and his Mysteries," massive bonfires were lit to honor Mithras on December 25. Christians were often guests at these bonfires and at feasts celebrating the birth of Mithras. Some scholars believe that when early Christian authorities realized that their followers were participating in pagan rituals, they made the decision to place Jesus's birthday on the same date.

Festival of Sol Invictus

Mithras was not the only god that competed for the attention of early Christians on December 25. Sol Invictus, god of the sun, was so important in Ancient Rome that the Circus Maximus was dedicated to him. In the third century, he was the official deity of Rome. His festival took place on December 25, and as described by The Colchester Archaeologist, was celebrated with chariot racing.

Christians in Ancient Rome took part in these festivities. Some believed in both the Christian God and Sol Invictus, much to the annoyance of church leaders. Leo the Great, the Bishop of Rome from 440-461 complained about "the ungodly practice of certain foolish folk who worship the sun as it rises at the beginning of daylight from elevated positions: even some Christians think it is so proper to do this that, before entering the blessed Apostle Peter's basilica, which is dedicated to the One Living and true God, when they have mounted the steps which lead to the raised platform, they turn round and bow themselves towards the rising sun and with bent neck do homage to its brilliant orb" (via University of Chicago).

The tradition spread fast

The nativity story comes from two books of the New Testament: Luke and Matthew. As noted by Newsweek, both were written approximately 80 years after the death of Christ. The idea of celebrating Jesus's birthday came a long time after his death, as well. Like many of the rituals celebrating his birth, the idea of having festivities for a birthday was initially seen as pagan. As explained by "The Birth of Christmas," the only celebrated birthdays mentioned in the Bible belong to Pharaoh and Herod.

Christmas was officially added to the calendar of feasts in 336. Celebrations spread throughout the Roman Empire, starting in the West and rapidly gaining popularity in the East within 50 years. Some regions including Jerusalem continued to celebrate Christmas on January 6 for decades until the December 25 date was enforced in the Byzantine empire around 575.

The spread of Christmas celebrations shaped Christianity by making the story of the birth of Christ a pivotal event. The Nativity story both solidified the idea that Jesus was a human being as well as God and increased ceremonies and prayers that revered Mary as his mother.

Yule and Christmas celebrations

Charles Dickens' choice to tell a ghost story in "A Christmas Carol" may seem surprising in a time when stories about the spirits of the dead crossing over to the land of the living are more closely associated with Halloween. However, ghost stories are intrinsically linked to Christmas by one of the holiday's major influences: Yule.

As Christmas celebrations moved further into Europe, they merged with another established holiday's traditions. While the name "Yule" is now often used synonymously with "Christmas," it was once an Old Norse holiday with its own traditions.

As explained in "Christmas: A Candid History" Yule (or Jul) was an old Norse celebration taking place in early winter, after the livestock had been slaughtered and ale brewed for the season. It likely included feasts, animal sacrifice, and the ritual drinking of beer. It is believed that these ceremonies also included a form of ancestor worship and ghost stories. Bonfires were lit and candles brought inside to warm the spirits who might visit. One massive burning log kept lit in the household was called a "Yule log," a tradition which has endured and become a staple of modern Christmas. Garlands of pine branches were also hung around the home, possibly to ward off evil spirits.

Persistent traditions: the Middle Ages

By the Middle Ages in Europe, Christianity was the dominant religion and Christmas celebrations rarely had to compete with festivals celebrating other gods. Still, customs from older festivals like Saturnalia endured. As described in History's History of Christmas, it was customary to attend church on Christmas Day. Afterwards, however, a festival full of excitement and drinking would begin. As in Saturnalia, tradition dictated that traditional social structures and class rules be ignored for the duration of the celebration. Commoners participated in a tradition similar to Halloween "trick-or-treating," in which they would visit the houses of the wealthy. At each house they would be served delicacies (and of course, more alcohol.) If they refused, the poor would play pranks on them.

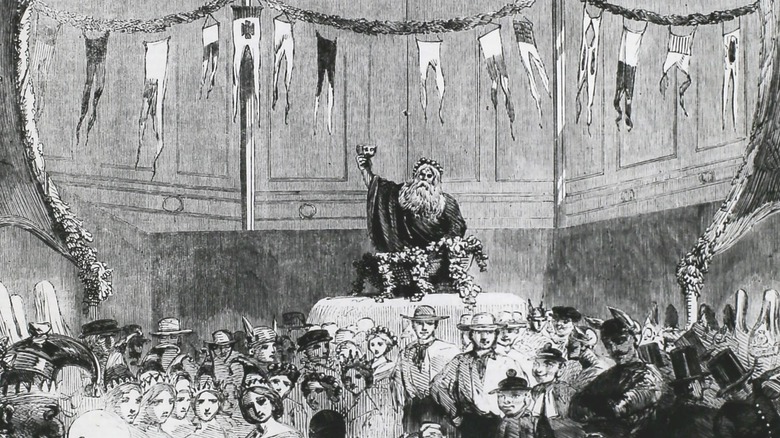

As detailed by Britannica, a version of the Saturnalia tradition of the "Mock King" also endured. One individual would be pronounced the "Lord of Misrule" or "Abbot of Misrule." They were responsible for setting up all the Christmas entertainment for the year, typically including costume parties and feasts. Celebrants would playfully give the Lord of Misrule the respect that they would give a real lord.

In Scotland, this tradition was transferred to a more controversial festival known as the Feast of Fools. During this early January holiday, celebrants pretended to honor a fake pope, who they selected by election. This individual was often referred to as the "Abbot of Unreason."