What Medieval Christmas Was Really Like

While Christmas as a holiday dates back hundreds of years, many of the traditions we associate with the holiday season date back to 100 years ago or less. Heck, Santa Claus didn't even make the scene until the early 19th century. Nevertheless, in Europe in the Middle Ages, Christmas was an extremely popular and beloved holiday that meant a couple of weeks of respite for poor overworked serfs and an excuse to show off wealth and seasonal largesse for feudal lords.

But if medieval Europeans didn't have Santa Claus or Rudolph or even Christmas trees, what did medieval Christmas look like? In some ways, the traditions were similar to those we have today — lots of food, games, and entertainment — it's just that the specifics — the stuffed swans, dice, and plays about talking donkeys — would be pretty unfamiliar to us. If you're interested in how Europeans spent each December in an era before fairy lights and the discovery of the turkey, read on to learn how to Christmas party like it's 1399.

The 12 Days of Christmas wasn't just a song

One of the elements that most distinguishes modern Christmas celebrations from medieval ones is the idea of the 12 days of Christmas. To a modern person, this idea largely survives in the song of the same title, often sung by people who have no idea when those titular days actually fall. For modern Americans, the Christmas season starts after Thanksgiving and lasts until you remember to take your lights down.

World History Encyclopedia explains that in medieval times, Christmas was the longest holiday of the year, and with good meteorological reason. During the winter, there wasn't much farm work that could be done, so many feudal lords allowed the peasants serving under them to enjoy a two-week respite from labor, lasting from Christmas Day on December 25 until Epiphany, also known as Twelfth Day, on January 6.

These 12 days consisted of all sorts of celebrations, from feasting to games to lots and lots of public drunkenness. There were also a number of other holidays commemorated within this span, including the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28, the Feast of the Circumcision on January 1, and St. Stephen's Day — aka Boxing Day — on December 26. Even when the Christmas season had officially ended, the celebrations would often continue with plough races on the first Monday after Epiphany and St. Distaff's Day — a day for a playful battle of the sexes – on January 7.

Going feast mode

A major feature of any Christmas celebration, medieval or modern, is a bountiful feast of traditional food. For Americans, this usually means turkey and pumpkin pie, for Brits it might be mince pies and pigs in blankets, for Germans lebkuchen and glühwein. But in medieval Europe, quantity and novelty often won out over tradition. As Medievalists.net explains, the winter season meant that crops had been harvested and animals had been slaughtered, and all that stuff wouldn't survive the whole winter, so now was the time to eat it. A commonly quoted example of Yuletide excess came in 1213 at the table of England's King John, who ordered for his Christmas table "24 hogshead of wine, 200 head of pork, 1,000 hens, 500 lbs of wax, 50 lbs of pepper, 2 lbs of saffron, 100 lbs of almonds" and "10,000 salt eels." (via Medievalists.net).

While this eye-popping meal is obviously an outlier, huge feasts were common at lords' tables. Common meals included beef, venison, pork, geese, and game birds, as well as show-stoppers such as swans or peacocks cooked with their feathers still on. Even peasants enjoyed an increased diet at this time, with lords supplying their people with special seasonal meals or even inviting them to the manor to share in their own bounty. And naturally, lots of beer and wine flowed for the holiday.

Bringing in the boar's head

While a medieval Christmas feast could be filled with all sorts of over-the-top food, one particularly startling dish was notable enough to merit its own carol. The Reading Museum explains that by the late Middle Ages, a standard event at English Christmas feasts was the presentation of a whole cooked boar's head, accompanied by song, dance, and ceremony. While the tradition presumably started with a genuine wild boar's head, by the late Middle Ages and early Modern period, the real meat-and-bone boar's head was replaced by a wooden effigy, the main reason being that the wild boar had been hunted to extinction in England by the 13th century. Sometimes a domestic pig's head would be used, or a real boar would be imported from continental Europe if the party was really fancy.

According to Hymns and Carols of Christmas, the song known as "The Boar's Head Carol," which is still performed as part of a Christmas ceremony in places such as Queen's College at Oxford, was first published in 1521. The song is a mixture of English and Latin, alternating lines such as "The boar's head in hand bring I, bedeck'd with bays and rosemary" with Latin verses like "caput apri defero, reddens laudes Domino" ("I bring the boar's head, returning praise to the Lord"). This is sung while servers carry in the boar's head, decorated with garlands, rosemary, and bay leaves.

Lighting the Yule log

Today, mention of a Yule log will most likely conjure up images of a TV broadcast of a gently crackling fireplace with soothing instrumental Christmas music played over it, or maybe a Swiss roll-style cake made up to look like a log covered in meringue mushrooms. However, the origins of the Yule log stretch back to the pre-Christian Germanic celebration of Yule, as the name suggests. How Stuff Works explains that Yule was (and is) a festival celebrated by Northern Europeans such as the Vikings to commemorate the winter solstice and welcome in the lengthening of days during the winter.

One of the common practices was the procurement of a Yule log, a stout and hearty oak log that would burn for a good long time. This process would be a family thing, with everyone heading out into the woods to find the best log possible. Over time, much superstition developed around the log, including that the log must catch fire on the first attempt, that the ashes of each year's log must be saved to be used in the following year's ceremony, and the log must burn continuously throughout the 12 days of Christmas. While some people may continue the traditional Yule log practice, modern urban dwellings have made the TV and cake versions more convenient for present-day celebrants.

Keeping the mass in Christmas

As with most things in life in medieval Europe, Christmas was church-centric in many ways. While much of the festivities were primarily about the leisure time afforded by the midwinter lull, Christmas was still officially a Christian holiday. The Reading Museum explains that the fourth Sunday before Christmas began the season known as Advent, which in medieval times was a period of fasting leading up to Christmas Day. While ordinary citizens did not have to fast every day, monks at the time were much more strictly observant. All the better, then, when the Christmas feast began.

The World History Encyclopedia explains that clergy ate quite well at Christmas time, with one English abbott known to order an entire wild boar each year, and other monasteries and abbeys enjoying increased bounties of fish and meat. Many monks got new robes at Christmas, as well as one of their twice-annual baths and tonsures (that Friar Tuck haircut).

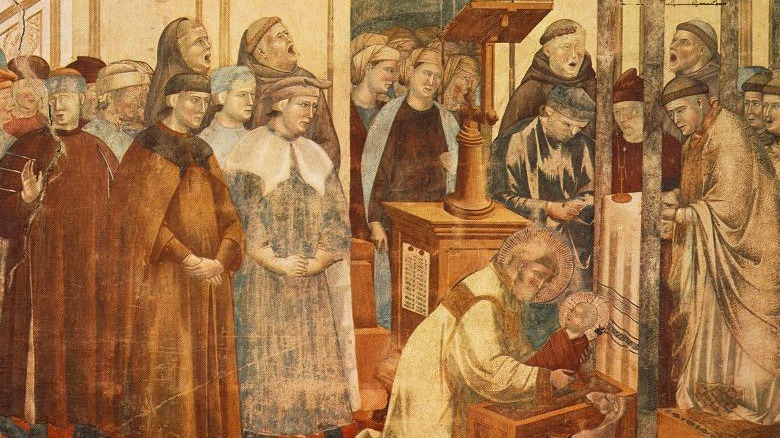

Christmas services themselves were exceptionally well-attended by people from every social class, with the traditional Christmas service growing increasingly elaborate over the years. The ninth century saw the introduction of a practice called troping, which was a kind of call-and-response song where half of the choir would sing a line asking a question such as "Quem quaeritis in praesepe?" ("Whom do you seek in the manger?") and the other half would sing the response (presumably the baby Jesus, but who knows).

Dramatizing the Nativity

As the World History Encyclopedia explains, the practice of troping would evolve over the centuries, eventually leading to dialogues and full-on dramatization of elements of the Christmas narrative within the church service. This ultimately resulted in the common medieval practice of Nativity plays, in which individual actors would perform roles such as the Magi and King Herod, or one of the Hebrew prophets such as Jeremiah or Daniel. According to History Today, as education spread and urban areas grew, religious plays became more common throughout the liturgical year, with Christmas plays chief among them. These plays were so popular that they eventually made their way out of the church and into the public square.

These dramas frequently expanded short passages from the Gospels into full-length plays. Two 15th century plays from England known as the Shepherds' Plays manage to stretch 11 verses from the Nativity narrative in the Gospel of Luke into 50 pages of stage time, with shepherds complaining about rent and the weather and such. Medieval Histories explains that the practice of acting out the birth of Jesus led to the earliest live Nativity scenes with real animals and people, which legend somewhat spuriously attributes to Saint Francis of Assissi. As the plays became more elaborate, they could include depictions of everything from the Fall of Man, to the Massacre of the Innocents, to the prophet Balaam's talking donkey.

Medieval Christmas was lit

While religious services were often at the heart of medieval Christmas celebrations, they were far from the only thing going. The World History Encyclopedia explains that the No. 1 most popular Christmas pastime in those days was getting drunk. In fact, people were known to get so drunk and rowdy during the 12 days of Christmas that it is well attested that lords would hire special guards just for the Christmas season in case of alcohol-fueled riots. This boisterous spirit would even infect the clergy during this time, with January 1 — officially known as the Feast of the Circumcision on the liturgical calendar — being unofficially known as the Feast of Fools. On this day, minor clergy such as subdeacons would wear their clothes inside out and drag a donkey into the church. Once they reached the altar, they would burn old shoes like incense and enjoy a feast of sausages and wine while making donkey noises.

The University of Leicester explains that by the Tudor period, the spirit of the Feast of Fools had developed to the point that an annual leader would be elected, known as the Lord of Misrule. The Lord of Misrule would preside over bands of masked merry-makers getting drunk and parading through town in elaborate costumes. Christmas was seen as a topsy-turvy time when fools were kings and kings were fools.

Resurrected knights and goats with threatening auras

The World History Encyclopedia explains that one of the most popular medieval entertainments at Christmas — one that survives to this day in some regions of England and Northern Ireland — was the mummers' play. Troupes of masked performers would go through the streets accompanied by musicians and dressed in strange costumes and put on traditional plays with stock characters and following a standard plot. Britannica explains that the basic skeleton of the plot featured Saint George fighting an evil knight (or other threat) and being killed, only to be resurrected by a doctor. Other characters used to bulk up this barebones story included a narrator, a jester, a man in drag, and Father Christmas. The death and resurrection narrative is probably linked to ancient metaphors about the sun at the winter solstice.

Medievalists.net describes another type of mumming, which was popular in medieval Scandinavia. During the dark nights of winter, groups of young men wearing scary masks and costumes would go from door to door frightening people and demanding food and drink. At the center of this group would be a young man dressed as a goat, in a costume made from real goat skins, complete with snapping jaws. This Yule Goat, as it was known, would barge into homes and frighten children, not leaving until the families had satisfied his hunger for cake, bread, and cheese.

Rolling dice for Christmas

As a time of leisure and rowdy celebration, Christmas in the Middle Ages was naturally filled with all sorts of games and sports. In fact, according to the University of Leicester, Christmas was a popular time for the playing of games that were banned during the rest of the year due to their association with wild partying and excess. These games included shuffleboard, skittles, and something called shove-halfpenny. The World History Encyclopedia adds board games such as checkers, backgammon, and whatever Nine Men's Morris is to this list. Another popular Twelfth Night game was king of the bean, in which a bean was hidden in a cake and the person who found it was named king. It survives to this day in various king cake traditions. Medievalists.net suggests that dice-playing was common throughout much of Europe at Christmas time, with even the French king Charles VII getting in on the holiday action.

Medieval France also enjoyed the Yuletide ritual of the game of soule, a vaguely football-esque game in which a piece of wood or a leather ball full of moss would be moved down a field by means of punches, kicks, or large curved sticks. The two teams would fight for possession of this ball with any kind of blows allowed, meaning that numerous injuries and even fatalities were common in these games, which would be played as an annual contest between teams from neighboring villages.

Electing the Boy Bishop

In the Western Church, December 28 is the Feast of the Holy Innocents, also known as Childermas. This holiday commemorates the children who were massacred by King Herod's men in an attempt to wipe out the newborn King of the Jews that the Magi mentioned to Herod. Medievalists.net explains that despite the bloody origins of the day, a fairly light-hearted tradition grew out of it. In various places in Western Europe, the Feast of the Holy Innocents was commemorated by the election of a boy bishop.

This practice dates back to at least the 12th century in England, where schoolboys would elect a bishop from among them, who would be dressed in a bishop's robes and led to church, where the children would perform a fake Mass, including a presumably rambling sermon from the boy bishop. After Mass, the child bishop leads the children in a procession, receiving money and food as gifts.

The version of the Christmas bishop recorded in Denmark is somewhat different, with a young man being consecrated as bishop by having his face blackened (yikes) and having a stick with candles on it put in his mouth. He would then perform a bunch of fake weddings in a funny voice in exchange for gifts. If the gifts offered weren't good enough, the Christmas bishop would hit the fake married couples with a bag of ashes he kept hidden under his cloak.

The medieval antecedent to Mariah Carey

One medieval Christmas tradition that has survived into modern times more than many others is that of the Christmas carol. However, as History Today explains, medieval carols didn't necessarily have much in common with modern versions. While these days the word "carol" denotes a Christmas song, particularly one with religious subject matter, originally it signified a specific form of song, specifically a dance that featured singing in which a leader sang the verses and a circle of dancers replied with the chorus. These carols weren't typically about Christmas, or even religious; in fact, they gained a reputation for being somewhat salacious until medieval clergymen transformed the naughty songs and dance into a new genre of seasonal religious song.

Early pioneers in the genre included Italian Franciscan friars in the 13th century and German Dominicans in the 14th century. English carols began being written later that century. The British Library explains that some of the earliest surviving Christmas carols include "Veni redemptor gentium" ("Come, redeemer of the nations"), "Puer nobis nascitur" ("Unto us a boy is born"), and "Corde natus ex parentis" ("Of the Father's heart begotten"). By the time of the Tudors in the Early Modern period, the Christmas carol was such a popular genre that King Henry VIII wrote one: the supremely underrated "Green groweth the holly."

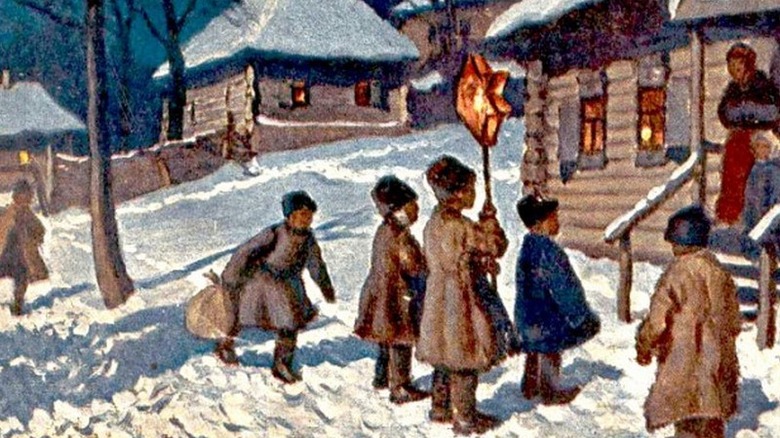

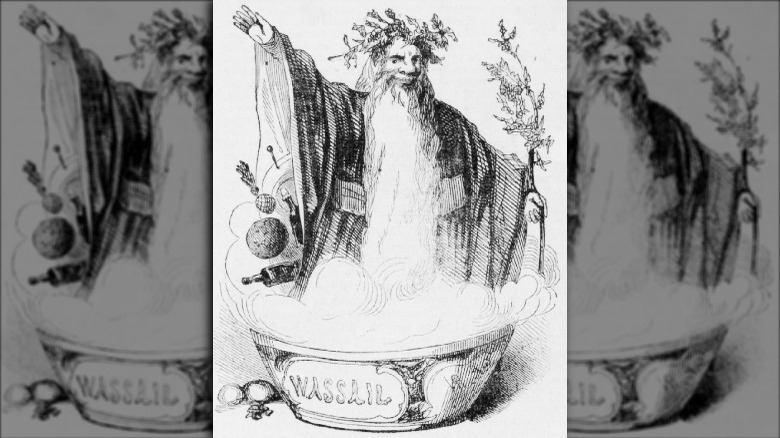

There they went a-wassailing

The traditional Christmas song "Here We Come A-wassailing" preserves the name of a medieval Christmas tradition that has survived in some areas but mostly evolved into the common holiday practice of caroling. Historic UK explains that wassail was (and is) a popular drink at Christmas time made from cider or ale, warmed and blended with spices, honey, and eggs, that was then put in a huge bowl and passed around from person to person. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon toast "waes hael," meaning "be in good health." The practice of wassailing that most resembles modern caroling involved merry-makers going door to door with wassail bowl in hand, singing songs and bestowing blessings upon the homeowners in exchange for gifts of money and food.

The other form of wassailing, however, the wassailing of the orchard, involves a group of people drinking wassail and singing to the health of the apple orchard in the year to come. The groups typically elect a Wassail king and queen and wander from orchard to orchard singing songs, banging pots and pans, firing shotguns into the air, and toasting the trees — literally, hanging pieces of toast in the tree branches. The loud noises are supposed to awaken the trees and frighten off any evil spirits that might cause a poor harvest in the year to come. Orchard wassailing occurs on Twelfth Night, January 5, marking a clamorous end to the 12 days of Christmas.