What It Was Really Like Picking Cotton In America

For many people sorting through racks of clothes today, cotton is nothing special. Indeed, it can seem like a pretty bog-standard fiber that merits little or no remark. It shows up alongside synthetic fabrics, other cellulose fibers like linen, and animal fibers like wool. Still, as MasterClass notes, cotton is darn near everywhere you look, from your clothes to your upholstery — even in your salad dressing.

Cotton has been big business for centuries. During the Industrial Revolution, increased mechanization made it all the easier to access cotton fabrics, while changes in agriculture meant that the American South started to produce higher-quality cotton in the early 19th century. Today, the United States remains one of the top cotton producers in the world.

But all that cotton didn't just magically fall off the plant and into textile mills. For much of human history, it was picked and processed by hand. And in the United States, those cotton pickers were often enslaved or, later on, people who were caught up in an exploitative system known as sharecropping. However they worked, they were also subject to seriously harsh conditions in the fields, from hot temperatures to endless, backbreaking work for hours under the eyes of unsympathetic overseers. This is what it was really like picking cotton in America.

The cotton industry encouraged slavery

In 19th century America, if you were picking cotton, you would have almost certainly been a slave. According to PBS, cotton became a prime crop in the American South during the 1830s and 1840s. Growers drew on a vast and complicated economic network that included textile factories to the north and a booming economic system across the Atlantic in Britain. And it was all built on the backs of slaves.

Though slavery had existed in the United States long before cotton became king, the growing demand for this luxury fiber helped fuel increased and intensified enslavement. As Vox explains, Black slaves forced to work picking and processing cotton could be seen as the primary driving force behind the nation's growing economy and ascendancy. Cotton was, after all, then the number one most exported good from the U.S. What's more, slaves made to pick thousands upon thousands of pounds of the fiber helped to make the South the biggest economic powerhouse in the entire country. For their efforts, enslaved cotton pickers worked and lived in brutal conditions, all to keep the money flowing.

Indigenous American people were also displaced to make room for cotton plantations. "Empire of Cotton" reports that quite a few tribes in prime agricultural territories like Alabama and Georgia were forcibly removed from their lands in the name of cotton.

Picking in cotton fields was laborious

Picking cotton is no easy task. In the U.S., cotton is ready for harvest in late summer or early fall, depending on the region, as per "The Second Great Emancipation." In harvest seasons, temperatures in the humid South can be blazing hot. Pickers would continue working until as late as December, giving them some relief from the heat, but no break from the rest of the labor-intensive process.

Picking by hand meant long hours spent in the field. Pickers experienced physical stress from stooping, picking, and dragging harvesting sacks through the field, as one man interviewed for the 1970 documentary "King Cotton" attested, saying that his knees and back bothered him after a lifetime spent picking the crop. "The Second Great Emancipation" notes that workers, forced to bend towards the plants all day long, were sometimes unable to straighten up at the end of the workday.

Growing the plant could be complicated, too. According to "The Second Great Emancipation," workers not only had to carefully consider when they would plant the cotton seeds, but then had to devote hours of labor to thinning the growing plants and pulling weeds around them. If it rained too much or not enough, farmers could become especially anxious about a reduced or ruined crop, though not nearly as much as if they spotted the infamously destructive boll weevil gnawing on their plants.

Cotton plants fight back

If a cotton plant was successfully brought to maturity, despite the threats of poor weather or leaf-chewing pests like the boll weevil, eventually it would produce the valuable fiber. But, of course, before it was baled up and sent off to manufacturers elsewhere, that cotton needed to be picked. Those who were obliged to pick it by hand soon learned that the plant didn't give up its bounty so easily.

Cotton has sharp, thorn-like protrusions on the boll, the central bud that produces the fluffy fibers everyone was going wild over (via Wessels Living History Farm). People who picked cotton by hand, like Mary Hyatt, reported that their fingers could become particularly sore after a day in the fields, especially if you were a child with little experience. Learning to pick cotton fast also meant doing your best to avoid getting stabbed over and over by the plants.

It can also be surprisingly difficult to pick cotton just right. According to Slate, people who were too aggressive might end up grabbing leaves and the sharp parts of the boll along with the fiber. But being too timid meant that you would only grab small bits of cotton, leaving the rest behind on the plant. When it came time to weigh the sack of collected cotton, you would have a pretty paltry harvest and a likewise sad payout at the end of the day (if you were getting paid at all, that is).

Early increases in picking were the result of brutality

During the 19th century, ballooning demand for cotton didn't just call for increased numbers of slaves or greater numbers of plantations throughout the South. It also meant that enslavers enforced increasingly brutal techniques and schedules to get more work out of each individual picker.

According to Slate, this ramp up in production did happen, but at a terrible human cost. An account by Charles Ball, who was enslaved on a South Carolina cotton plantation in the early decades of the 19th century, details some of the immense pressure faced by enslaved people picking cotton. "Captains" were tasked with setting a frenzied pace and anyone who couldn't keep up could face dire consequences beyond an aching back and sore hands. Those who fell behind were often subjected to brutal whippings.

It was all ultimately known as the "pushing system." Over the years, slaves were expected to clear more and more land, going from some 5 acres per person in the first half of the century, to 10 acres in the decades just before the Civil War. For operations that counted productivity by pounds of cotton picked, it was much the same. Anyone falling short could be beaten and was certainly subject to intense verbal abuse. The accounting of cotton, with the weight of worldwide demand at its back and the lure of profits for plantation owners, could be merciless.

Cotton picking was seemingly never-ending

One might think that, for all of the brutality and harsh conditions involved in picking cotton by hand, it was at least over in a season's time. Not quite. That's because cotton doesn't mature all at once, meaning that it was often picked in multiple passes before a plant was fully depleted of fiber. Charles Ball, an enslaved man who shared his narrative in 1837's "Slavery in the United States," explained that there were generally three pickings. The first grabbed fiber from the bottom of the plant, the second from the middle, and the final picking finished off the cotton from the plant's top.

Separating fiber and seeds was labor intensive, too, especially when it was done by hand. Even careful and skilled pickers could only keep so much plant matter out of the fibers. According to "Cotton and Race in the Making of America," a single person would need an entire day to separate out the seeds from a single pound of cotton. Compare that to the hundreds and thousands of pounds expected from a field in a given pass, and you can see how cotton was often a pricey luxury good for the time.

Today, "ginning" cotton by hand, as it's known, is largely the province of hand spinners. SpinOff notes that there are two major ways to separate seed from fiber, namely teasing the seeds out from the tangle of cotton and using a dowel to roll them out of the boll.

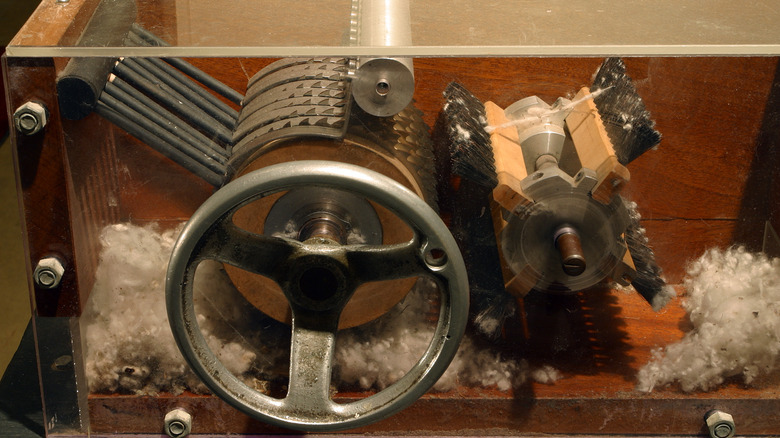

The cotton gin increased demand for field labor

The laborious process of picking or rolling cotton seeds out of picked fiber could only go on for so long in the face of the Industrial Revolution. For those who went through the United States education system, chances are good that you at least saw a passing mention of the revolutionary cotton gin. According to the National Archives, Eli Whitney invented this device that more or less automatically separated seeds from the valuable cotton fibers, patenting it in the late 18th and again in the early 19th centuries after much legal drama.

Fighting over patents and figuring out just who was going to get paid for this revolutionary invention was surely exhausting, but try to tell that to enslaved people of the time. The cotton gin, which sped up the process of picking seeds out of the cotton fiber, put even more pressure on plantations to produce larger amounts of cotton. Slavery grew as a result. By 1860, with the American Civil War on the horizon, about one in three people in the South was a slave (via National Archives).

Ultimately, the gin had a major role in the spread of slavery throughout the nation as the market for this crop ballooned. Plantations likewise grew in size, to such a point that urbanization in the South slowed as more land was set aside to grow cotton. Meanwhile, the North saw serious gains in its industrialization and therefore that region's economic power.

Sharecropping continued cotton picking after the Civil War

Like so many other aspects of American life in the mid-19th century, the plantation network was completely upended by the Civil War. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, ostensibly freed all slaves in rebellious states, the National Archives reports. Yet, slaves in Union border states and Union-controlled territories were out of luck, and the Smithsonian notes that Black people in Texas weren't aware of their legal emancipation until well into 1865. Ultimately, however, slavery was abolished throughout the U.S. At least, it was in name. In its place, cotton continued to grow and was picked by people working under the exploitative sharecropping system.

According to History, sharecropping was a farming arrangement wherein tenants rented small portions of land from an owner. They were supposed to give the landowner a portion of their crop each year in payment. Sharecropping often replicated the old, decidedly unequal relationship between white landowners and Black workers. Sharecroppers often had to pay their landlords for the use of tools, for example, putting them in persistent debt. The racist attitudes of the Reconstruction South also meant that those who spoke out or tried to break away from sharecropping could face serious violence.

Many sharecroppers, regardless of skin color, found themselves stuck in the arrangement. Even though cotton prices began to drop as the century moved on, sharecropping trapped many Southern communities into producing the crop anyway, per "The Second Great Emancipation."

It delayed some kids' education

For many families, especially those working relatively small plots of land under the sharecropping system, children were required to help with picking cotton. According to the "From the Field to the Classroom: The Boll Weevil's Impact on Education in Rural Georgia," kids could also be better pickers than some adults, given that they were smaller and somewhat faster. Yet, this presented a problem. The cotton harvest often overlapped with the beginning of the school year, meaning that adults sometimes had to choose between sending their children into the fields to pick cotton or into the schoolhouse to receive an education.

For many cash-strapped families, young ones were held out of school to help earn money by picking the crop. This was especially tough for Black families, according to the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs. Not only were they more likely to be on the losing end of sharecropping (via History), but their segregated schools were often poorly supported. In some cases, schools reserved for Black children delayed opening until January.

This is a problem that persists in the modern day in other nations. The Human Rights Watch reported in 2017 that government officials in Uzbekistan forced both adults and children to pick cotton. Though children reportedly completed their labor after school in this case, Uzbekistan has a track record of interrupting education for both students and teachers to undertake field work. Neither does it seem as if these underage laborers are given any sort of protective equipment, despite the use of pesticides on cotton crops.

Cotton picking pay was paltry

In the United States, those who picked cotton under the sharecropping system were often paid very little. According to Buzzfeed, 103-year-old Madie Scott reported that she received only 50 cents a day for her work. Oh, and that workday typically lasted from 3 a.m. to 5 p.m., with a noontime lunch break. Scott says that she began her work picking cotton when she was 12 and living in Georgia, before eventually moving to Miami at age 16 because she believed she could earn better money in Florida. According to Scott, the pay was still better than other jobs available to Black women at the time, which included poorly compensated work as cleaners and childcare workers.

Pickers were typically paid by the pound and frequently worked in family groups to bring in more income. In one account shared by Voice, a picker recalled that 1940s wages typically came out to four cents per pound of picked cotton. If an adult picked 100 pounds in a day, as was considered the average, they earned a mere $4 for their hard work. Even this humble pay would eventually be taken away with the advent of a new piece of machinery: the mechanical harvester.

Mechanical harvesters didn't take over until the 20th century

The first mechanized advancement in the cotton industry was arguably Eli Whitney's cotton gin (via National Archives). Mechanical cotton pickers first debuted around 1832, with Cyrus McCormick's reaper, according to "King Cotton in Modern America." However, such equipment wouldn't become more common until more than a century later, after World War II. This didn't happen without plenty of angst about the future of the industry, either. "The Second Great Emancipation" notes that media of the era sometimes showed farm equipment as an evil force that took honest work out of the hands of laborers. Others argued that mechanization wouldn't be necessary if only landowners paid pickers a respectable wage. And surely the first sharecroppers who were outcompeted by a relentless combine harvester felt the pain of losing their livelihoods.

Yet, all this change was inevitable. According to the Wessels Living History Farm, Black sharecroppers had begun to leave the region in droves, moving North for better jobs (getting some small measure of relief from the entrenched racism of the South was surely part of it, too). This eventually led to a dramatic change in population in the region, with some 21% of rural Black people leaving the South. It all contributed to the collapse of the sharecropping system and the undeniable need for mechanical assistance in its wake.

Today, it's all done with large machinery

If you happen across a field of cotton in the modern United States, you'd be hard-pressed to find any laborers harvesting the fiber by hand. In the modern agricultural landscape of American cotton, machines have all but taken over.

Hundred Percent Cotton explains that there are two major ways that farmers harvest the crop today. They may choose to use a mechanical cotton picker or a similarly named mechanical cotton stripper. Pickers take the fiber and leave the rest of the plant more or less intact (and out of the cotton harvest), while the cotton stripper brings in more vegetable matter that will need to be processed out later. That's the norm in the U.S., but farms in other nations still use hand pickers to harvest the crop.

According to The Story of Cotton, these mechanical assists mimic what human pickers have been doing for centuries, just at a greater speed and with very different fuel intakes. Afterward, many farmers will leave the rest of the plant in the field to be tilled into the soil. Those using a method called conservation tillage, will leave the picked plants on the surface. By spring, the fields should be ready for planting yet again.