The Untold Truth Of The Mummy

Universal's monster movies forever changed the way we think of classic characters like Frankenstein's monster, Dracula, the Wolfman, and the Mummy. But be honest: how much do you really remember about this undead, bandage-clad Egyptian? Probably not a whole heck of a lot, right? Let's unravel the truth about one of the horror genre's favorite ghouls.

(This article is all about mummies in the movies, but if you wanted to read about historical mummies, we've got you covered.)

Contemporary reviews were less than kind

The Mummy and its string of unofficial sequels are totally iconic movies today—especially at Halloween. We all know someone who's wrapped themselves in toilet paper and gone shambling through a party, arms outstretched, trying for a cheap laugh. They're beloved today, sure, but when the original Universal mummy movie came out, some reviewers were less than kind.

In 1933, the New York Times wrote that the film's "photography is superior to the dialogue," which ... ouch, that's pretty harsh. You could honestly say that for a lot of 1930s films, so seriously, cut the poor Mummy a break. But they go on: "For purposes of terror there are two scenes in The Mummy that are weird enough in all conscience ... But most of The Mummy is costume melodrama for children." To be fair, it was 1933, so these were children of the Great Depression who saw real terror in the real world, not just on Call of Duty. Spooky mummies probably meant nothing to them.

The two scenes the Times found suitably terrifying—even for the unflappable little rascals—were the moment the mummy sits up, driving one archaeologist mad, and the scene where the pre-mummified Imhotep is embalmed alive. We agree: that's the kind of terrifying that gets even worse the more you think about it ... and the more you actually know about just how embalming works.

You're remembering Boris Karloff and the bandages completely wrong

There's a few big names that you associate with Universal's iconic monsters, and Boris Karloff—then billed as "Karloff the Uncanny"—was the original Mummy. So surely it's Karloff's take on the character that brings to mind the traits we all associate with the Mummy, like the bandages, the groaning, and the shuffling through life, right? Not exactly.

For the entirety of 1932's The Mummy, in fact, Karloff's Imhotep is wrapped in bandages exactly once: when he wakes. That waking scene (where he shuffles a bit, too), is actually set ten years before the rest of the movie, so it's not surprising that the bandages come off, one way or another. Karloff's mummy is intelligent, so much so that he's even given himself the new name of Ardath Bey.

The image of the shuffling, bandaged mummy comes from the later incarnations of the creature, and Karloff wouldn't be back for any of them. This mummy—a completely different one named Kharis—was played by a whole slew of actors that included Tom Tyler, Eddie Parker, and more famously, Lon Chaney, Jr. and Christopher Lee. That group actually started with The Mummy's Hand, released in 1940. Now you know.

Lon Chaney's mummy movies were set way, way in the "future"

We tend to think of the Mummy series as belonging to the horror genre, but if you want to be picky, they actually dabbled in a bit of futuristic sci-fi, too.

The last of the Lon Chaney, Jr. mummy movies, 1944's The Mummy's Curse, is actually set 25 years after the events of The Mummy's Ghost, which was released earlier that same year. If you do the math and follow the lore, that technically means it was set in 1995. The future!

That's definitely not a plot point in the movie, and we're pretty sure that the filmmakers never actually did the math when they just kept adding on the decades that the mummy was asleep, or trapped, or whatever. We get it. They're writers and artsy people, not mathematicians.

The Mummy's Curse is significant for another reason, and before everyone starts complaining about a female mummy in the reboot, it's already been done: right here. Her name was Ananka, and once she shed the bandages and became a little more human, she was played by an actress named Virginia Christine. How's that for equal opportunity?

Much of the backstory was cut for violation of the Hays Code

The basic story of Karloff's original Mummy is the most familiar one. Imhotep is returned to the world of the living by an idiot archaeologist who has clearly never seen a horror movie before, and once he heads out into the real world, he finds the modern-day reincarnation of the woman he had loved centuries ago. Wacky hijinks ensue.

The original script called for a series of scenes that showed Imhotep's beloved being reincarnated through the centuries, until finally being reborn into the modern Helen. They never made it into the final film, though, because movie censors deemed them too blasphemous, so they were cut. This was much to the disgust of the actress that played Helen, Zita Johann, who believed in reincarnation (after all, since when do suits give a sniff about what some puny actress thinks?)

That entire part of the movie was found to be in violation of the Hays Code, which was Hollywood's attempt to regulate what made it onto the screen. There were a whole slew of rules and regulations about what couldn't be included in movies, including statutes that said religions were not to be ridiculed, and ceremonies should be respected.

The code also outlawed nudity, the suggestion of nudity by showing people just in silhouette, dancing that could be deemed indecent, obscene gestures, and profanity. Obviously, that's no longer in effect, thank Imhotep.

He's the only Universal monster with no mythological or literary background

Dracula has Bram Stoker, Frankenstein and his monster came from Mary Shelley, and the Wolf Man has his roots in mythology (and, to be fair, so does Dracula). But the mummy's the odd one out because there's absolutely no direct literary or mythological basis for him.

Mummification in ancient Egypt means the removal of all internal organs, in a process that we'd recommend you don't read up on. The point of mummification was to preserve the body for the next life, as with the story of Osiris, not for it to stay in this one. The mummy movies usually change the lore to say that the person had been buried alive for some horrible crime, and so they had all their organs terrifyingly intact.

That said, there were some stories written about mummies in the 19th century. Jane Webb's 1827 The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century is the first to feature a revived mummy, but it's definitely not the mummy we all know and love. It's not until Theophile Gautier's short story "The Mummy's Foot" in 1863 that we start getting a little supernatural. That one's about someone who buys a mummy's foot as a paperweight (as you do), and starts having dreams about the Egyptian princess it once belonged to.

None of them feature a monstrous mummy, however—it's more about love across the ages and past life and death, which we think we can all get behind. It's not until Arthur Conan Doyle that we get a mean mummy, and it's his stuff that likely had the most influence on Universal screenwriters.

The story was originally called Cagliostro

The Mummy is the first to get an official reboot, but in the original lineup it came after Dracula and Frankenstein. Those two were such big hits that Universal execs knew that they had a potential goldmine on their hands, so they started development on this new project with the idea that they wanted a monster movie that would star Boris Karloff. They even developed an idea, but it definitely didn't have a mummy in it.

The film was going to be called Cagliostro, and Karloff was going to star as a 3,000-year-old sorcerer who kept himself looking fresh and lifelike by injecting his body with nitrates. During his original lifetime, he was betrayed by a lover, so he walked the Earth still fueled by rage, and killed anyone he found who happened to look like that original woman. It's not a bad idea, really, and we could totally get behind it.

That said, they didn't even need all that magical mumbo-jumbo — they could've just made a movie about the real Count Cagliostro. He was awesome! A forger, con artist, fake-magician, faker-alchemist, and one of the spirits Aleister Crowley claimed had reincarnated into him, he conned countless people out of all their gold, co-founded Egyptian Freemasonry, and ultimately found himself exiled by the Pope for being, well, him. HBO, please film what Universal would not.

It was only set in ancient Egypt because of the discovery of King Tut's tomb

Amazingly, the only reason we got The Mummy the way we know it is because real-life history — and some funky maybe-curses — intervened.

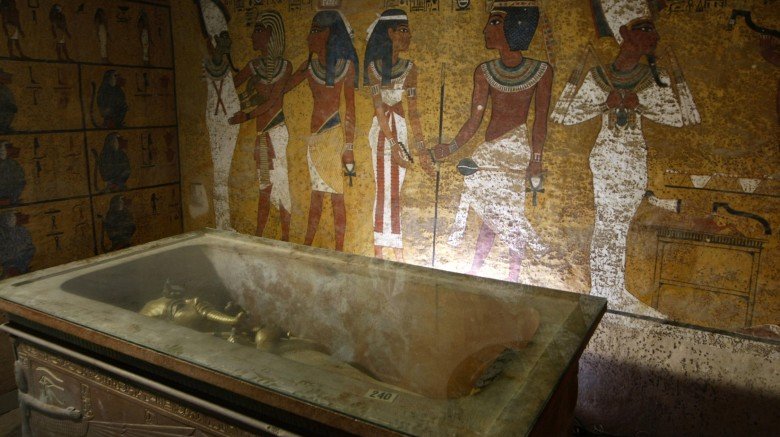

Universal hired a screenwriter for the project, and his name was John Balderston. Before trying his hand at penning movies, Balderston was a well-known newspaper correspondent of the variety that tended to get sent all over the world to report on some of the most epic discoveries of the day. In 1923, that was Howard Carter's opening of King Tutankhamen's tomb, and Balderston was there. He was one of the guys that was on hand when Carter went in and started pulling out all sorts of artifacts, and that makes us severely jealous.

Balderston's experiences in the desert of Egypt gave him the background to write something set there, and honestly, it's more than a lot of screenwriters have. Cagliostro became The King of the Dead, which then became Im-Ho-Tep, which finally became The Mummy.

Imhotep was based on a real person

The first mummy, Imhotep, wasn't just based on a very real person, he was based on a very important person. Imhotep was something of a rags-to-riches story, born poor and rising to become one of the foremost advisors to the pharaoh Djoser. More importantly, Imhotep was responsible for the design and building of Egypt's first pyramid, the Step Pyramid at Sakkara.

Even then, they recognized that he was a pretty big deal. Originally elevated in the ranks of Egyptian mythos to become a son of the god Ptah, he eventually became a god himself and was revered at Memphis for his brilliance as a physician. He was given his own priesthood, and was thought to be something of a go-between for the people and the gods. Imhotep was the one that the people prayed to when they wanted someone to speak on their behalf to a greater power, and even the Greeks still recognized him as a deity when they combined him with their own Asclepius.

He wasn't just popular for a few centuries, either; he lived around 2600 BC, and was worshiped into the 7th century AD. Not bad, especially for a poor kid from the projects.

The idea of the mummy's curse is older than you think

We've all heard the stories about the curse of the mummies disturbed by either grave-robbers or archaeologists, depending on your point of view. It's usually King Tut that gets the most credit for doing the most amount of damage with his curse, and if you're even the least bit familiar with history, you'll know it's complete bunk.

It makes a great story, though, and that's part of what makes The Mummy such a creepy movie. (And one that's actually worth rebooting, for once.) But the idea of the mummy's curse isn't just misidentified as having something to do with Howard Carter, the famous "cursed by Tut" guy, but it's a lot older than the 1920s excavation of Egypt's most famous tomb.

Some Egyptologists think that the "curse" really was put in place to discourage tomb robbers, and that the idea dates back to the time the tombs were first built. But the idea came to Europe years before Carter embarked on his Egyptian endeavors, and they came in a weird sort of way. In the 1820s, the West End of London, just outside Piccadilly Circus, was the location of a weird stage show that inspired Jane Webb to write her book, The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century.

The show was described by Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat as being the inspiration that kick-started the idea of the mummy's curse, and it was basically a show where a very real mummy was unwrapped on stage, much to what we imagine was the combined delight and horror of an audience full of cynical city-dwellers who, up until perhaps that moment, had thought they had seen it all. That was a full century before Carter was named by popular opinion as the target of a curse, eventually leading to the development of one of our favorite movie monsters of all time.

Who says that nothing good and culturally significant ever comes out of a striptease?