Colorado Coalfield War: The Bloodiest Labor Dispute In US History

When workers on the Colorado coalfields decided to strike in 1913, they had no idea that the strike would last over a year. They had no idea how many lives would be lost. They had no idea the lengths that the coal companies would be willing to go in order to suppress the strike.

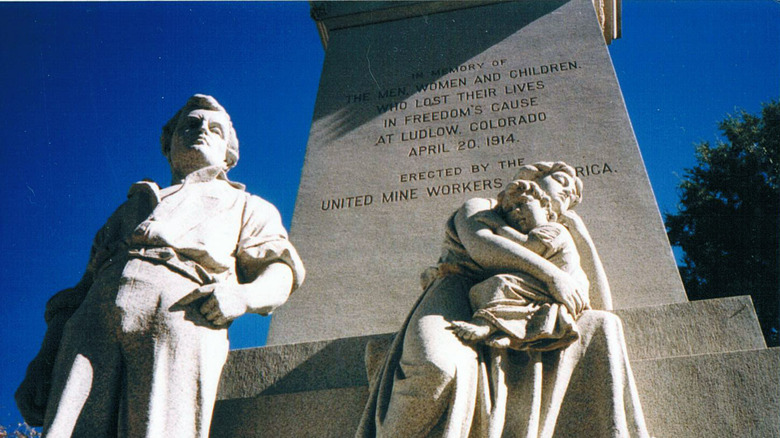

Known as the Colorado Coalfield War, it's estimated that between 69 to 199 people died during the strike, making it, as of 2021, the "bloodiest labor dispute in American history." And yet for most of the 20th century, it was overlooked in American history classes. Historian Howard Zinn first learned about one of the massacres that occurred during the strike when he heard the song "Ludlow Massacre" by Woody Guthrie. "Nobody had ever mentioned [it] in any of my history courses."

In 2009, the Ludlow Tent Colony Site was designated as a National Historic Landmark. Meanwhile, mining towns like Ludlow that were once centered around CF&I have turned into ghost towns. And as companies like Amazon are toying with the idea of factory towns once more, it's worth looking back to see what really happens in a factory town. This is the Colorado Coalfield War: the bloodiest labor dispute in US history.

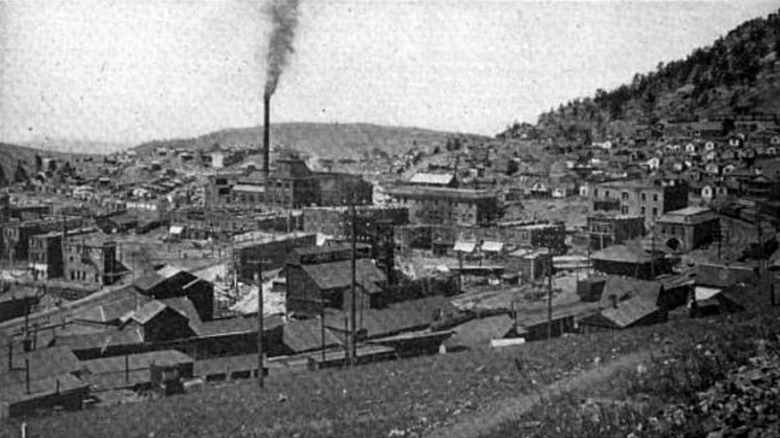

Rockefeller takes over Colorado Fuel and Iron

Founded through a merger in 1892, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) was producing the majority of Colorado's coal and coke by 1900 and had over 15,000 workers. In "Uniting Mountain & Plain," Kathleen A. Brosnan writes that after CF&I issued new stock in the 20th century in order to finance repayments, the company was taken over by John D. Rockefeller, who became the principal shareholder in 1903 along with his son, John Jr.

Although CF&I suffered from incompetent management and corruption, Rockefeller was still recommended the investment by George Gould, according to "Mother Jones" by Simon Cordery. And when the instant profits that Rockefeller expected didn't appear as planned, this "stiffened [Rockefeller's] already firm opposition to unions."

In "Populists and Progressives," Norman K. Risjord notes that in Colorado, as in other states like West Virginia, large corporations such as this one were able to pay off local governments and mine inspectors. And with the help of company towns and company stores, the miners were kept entirely under company control, with an average pay in Colorado of $370 per year.

Mining strikes in Colorado

In 1903 and 1904, Colorado saw a series of strikes by miners and mill workers. This became known as the Colorado labor wars and according to "Radicals in the Barrio," this was the "first significant attempt to spread a strike throughout the industry." Led by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), the major issue was the 8-hour workday.

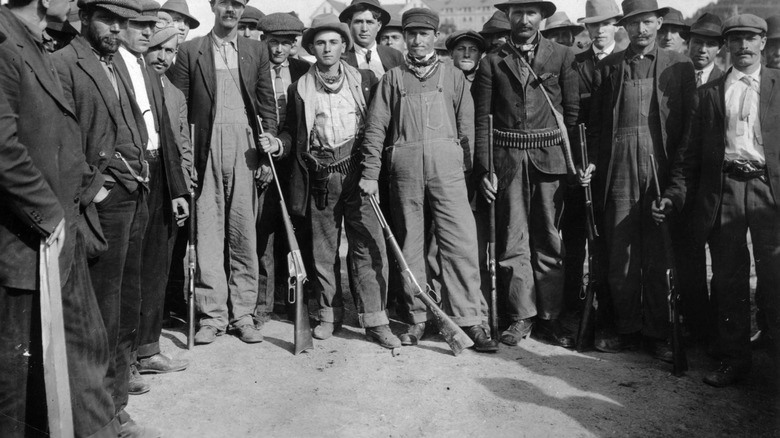

The strikes were brutally repressed by the state militia that was "paid for by the mine companies and were housed in mine company quarters," Robert Justin Goldstein writes in "Political Repression in Modern America from 1870 to 1976." Pinkerton agents were also used as strikebreakers. The strikes also lost strength when United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) president John Mitchell called for a second vote, resulting in northern workers returning to work while southern workers continued to strike, per "Killing Coal" by Thomas G. Andrews. Over 400 union miners were deported as troops "refused to obey habeas corpus orders from the courts." Over 175 were arbitrarily arrested and held for months. Coal companies also resorted to beating union members or dynamiting homes, Andrews writes.

After unions lost the Colorado labor wars, coal mine owners started recruiting Mexican, Southern and Eastern European, and Japanese workers as nonunion miners. William Wei writes in "Asians in Colorado" that since Japanese workers were kept from working by the racism of the United Mine Workers, "as a general rule, wherever union organizing was ineffective, it was easier for Japanese to find employment."

Working conditions at CF&I

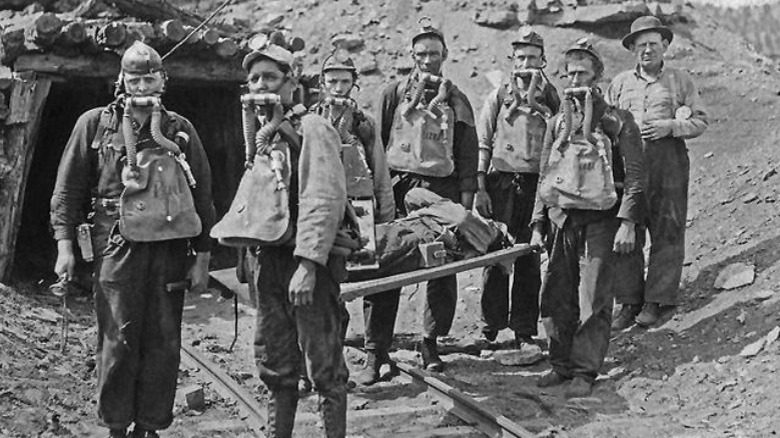

Working conditions for miners across the United States were deadly and things were no different at CF&I, even after the Rockefellers assumed control. According to "Killing Coal," between 1884 and 1912, fatalities for Colorado coal miners averaged more than twice the national average. And in the early 1910s, a series of explosions pushed the average mine fatality rate even higher, "above 10 deaths per thousand." In Pre-1963 Colorado Mining Fatalities, Gerald E. Sherard notes that in 1910 alone, 131 people died from explosions in CF&I mines. Other mining companies recorded similarly high fatalities from their own explosions.

The 1910 Starkville Mine explosion was caused when a spark from a short circuit of a trolley ignited the coal dust. The Denver Post reports that the explosion was so big that "it was heard and felt in Trinidad seven miles away." And as rescuers tried to find survivors, they ran into pockets of toxic fumes and afterdamp, "a poisonous gas mixture left after an explosion," and would themselves require emergency treatment. It was ultimately found that the explosion occurred because CI&F "insufficiently sprinkled the mine to keep the coal dust damp" despite the fact that the state had repeatedly warned them to do so.

Explosions and fires happened on bad days but good days weren't much better. The buildup of coal dust inhaled by miners would eventually cause pulmonary fibrosis, also known as miners' asthma or pneumoconiosis. "The condition asphyxiated its victims with agonizing slowness."

Under coal company control

When accidents did occur due to managerial incompetence or company negligence, the workers had little recourse. Historian F. Darrell Munsell, per "Radicals in the Barrio," notes that especially in the southern coalfields, coal operators did everything they could to control "all local public officials, from county clerks to sheriffs and their deputies on up to the judges." Jury tampering became the norm since sheriffs were the ones who came up with the jury lists. Coroners' juries were also "part of the companies' political machine."

This phenomenon was significantly more present in the southern coalfields, where workers lived in company camps akin to "shanty towns," than in the northern coalfields, where more miners lived off-site. Scott Martelle writes in "Blood Passion" that in the closed camps in the south, in addition to being "closed economic systems," all judicial issues were handled by the sheriff and there was no court system. Workers essentially had "no machinery that he could call to his aid in redressing a wrong." Meanwhile, company spies were littered everywhere, from the company saloon to the mines, and they kept a close eye on everything to report back to the operators.

Who are the UMWA?

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was founded on January 25, 1890, in Columbus, Ohio by members of the Knights of Labor and the National Progressive Union of Miners and Mine Laborers. The Library of Congress writes that the union was established to address three main issues: the development of mine safety, the improvement of workers' independence from the mine owners and company stores, and the ability of miners to have collective bargaining power.

The UMWA was focused on organizing and supporting coal mine workers in both West Virginia and Colorado and in both places, they were met with violence. According to the National Park Service, when UMWA heard that workers in Paint Creek and Cabin Creek were striking, they lent their full support to the strikers and sent the organizer Mother Jones to the region. In response, coal mine operators hired private security firms to violently suppress the strike. The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike lasted a little over a year, from April 1912 to July 1913. Times West Virginian writes that the strike resulted in 50 direct deaths, while countless others died from starvation and malnutrition, making the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike one of the deadliest labor conflicts in United States history.

The first shots in Colorado

When the UMWA set out to help miners in Colorado organize, coal mine owners sought to immediately suppress any influence they could potentially have. On August 16, 1913, Gerald Lippiatt arrived in Trinidad, Colorado from the northern coalfields to continue the organizing work he'd been doing for UMWA, per the United Labor Bulletin, Vol. VIII. As Lippiatt walked down the street on a Saturday evening, he was shot by George Belcher and Walter Belk, two Baldwin-Felts detectives who'd recently been deputized, according to "The Zinn Reader" by Howard Zinn.

Belcher and Belk were released on a $10,000 bond and a coroner's jury was formed, which included the manager of the Wells Fargo Express Company and the president of the Sherman-Cosmer Mercantile Company. In the end, the jury determined that the death was a "justifiable homicide."

After the murder, union organizing didn't cease and instead increased as secret meetings were held and plans for a convention were made. The Trinidad Convention was held on September 16, 1913, and over two days workers listed their grievances, which included wage theft, violation of the 8-hour law, and the fact that their wage spending was limited to company stores and saloons.

Miners make their demands

After hearing everything, the convention of 280 delegates made their list of demands. According to the University of Denver, these demands included recognition of the UMWA, enforcement of the 8-hour day, payment for dead work, enforcement of Colorado mining laws, and the abolition of armed mine guards. While there was also a demand for a wage increase, the workers ultimately wanted "a change in both the labor and community relations found in the coal camps."

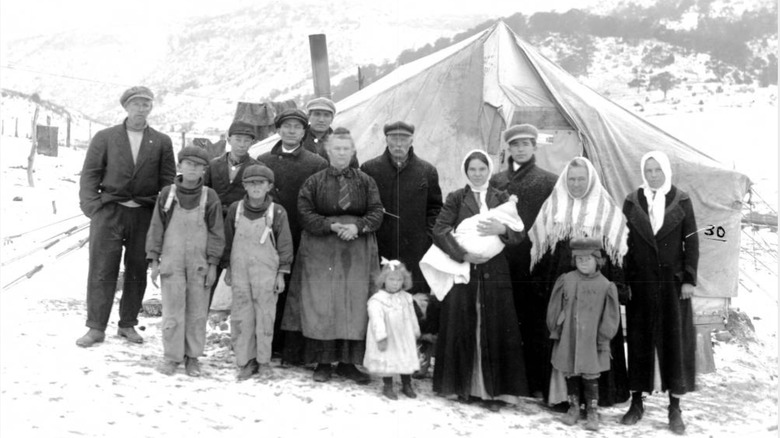

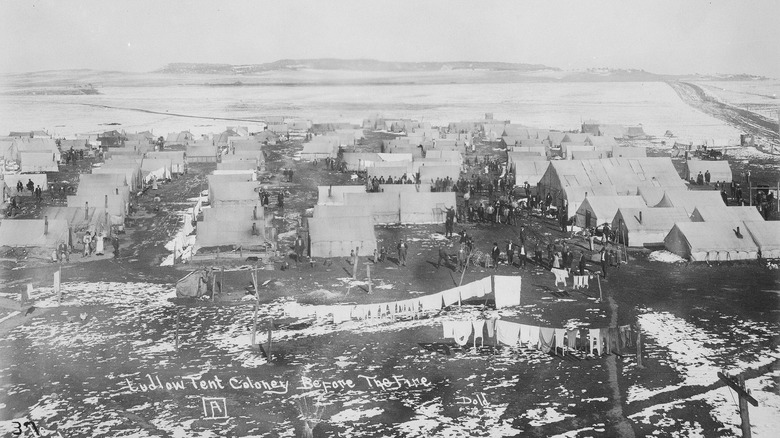

After workers announced these demands on September 23 and declared a strike were they not met, the coal operators retaliated by immediately evicting the mine workers from their homes. 11,000 miners, roughly "90% of the workers in the [southern] mines," moved out of the mining camps and ended up in tent cities established by the UMWA, according to Intermountain Histories. Unfortunately, not all of the tents arrived on time and as it rained and snowed, one observer noted that "the elements seemed to be in league with the operators," per "The Zinn Reader." There ended up being several tent cities, but the largest ones were at Ludlow and Aguilar.

In Ludlow, there were 400 tents for 1,000 people, including 271 children. During the strike, which lasted until the end of December 1914, 21 additional children were born into the tent colony. The Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project also notes that the Ludlow tent colony was relatively heterogeneous, though mainly European immigrants, and within the colony, 22 different languages were spoken.

Violence during the strike

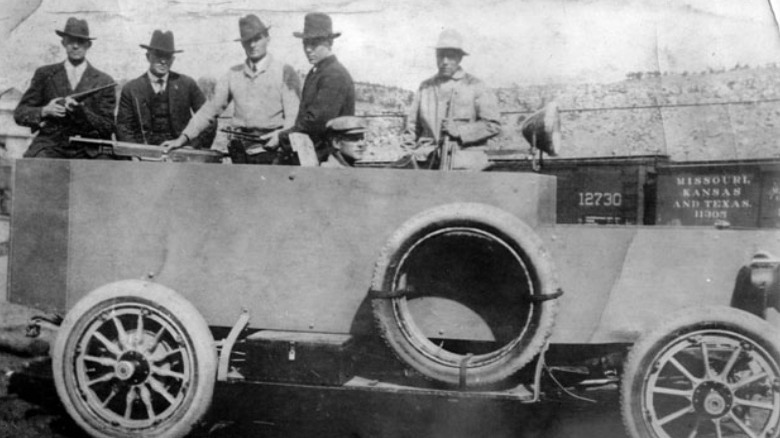

Eight tent colonies in total were established and violence against the striking workers began almost immediately. According to "The Zinn Reader," the Baldwin-Felts detective agency mounted a Gatling gun onto a "special auto, steel-armored," and drove it through the countryside attacking striking workers and their families. Known as "the Death Special," the Baldwin-Felts agency attacked the tent colony at Forbes with it on October 17. One man was killed and a 10-year-old boy's leg was riddled with nine bullets. When G.E. Jones tried to take a photograph of the armored car, he was beaten unconscious and then arrested for "disturbing the peace."

Coal companies also harassed the tent colonies with "high-powered searchlights" at night and mine guards fired into a group of striking workers on October 24 in Walsenburg, killing four people. According to The Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project, the constant harassment was intended to provoke the striking workers into being violent as well, which would give the governor an excuse to bring out the National Guard. "This would shift the financial burden for breaking the strike from the coal companies to the state."

The striking workers fought back against the private militia and the mine guards and several mine guards and clerks were killed during the strike. And Belcher, Lippiatt's murderer, was also murdered "by an unseen gunman." The striking workers would also harass and threaten non-union miners who continued to work, also known as scabs.

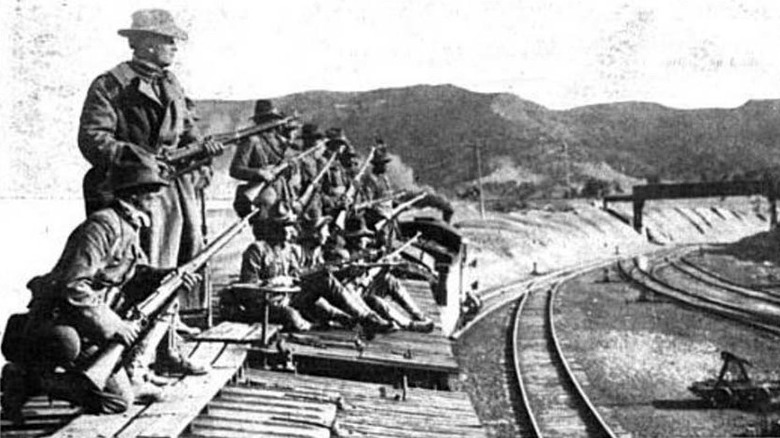

Bringing in the National Guard

On October 28, 1913, the Governor of Colorado Elias Ammons declared martial law, ordered the Colorado National Guard to move into the strike district, and prohibited the importation of any more strikebreakers from outside of Colorado. However, the ban on imported strikebreakers was virtually unenforced, according to "The Zinn Reader," and was soon rescinded.

In the end, the decision to bring in the National Guard was less based on the violence occurring during the strike and more on the cooperation of the bankers. In a letter to Rockefeller Jr., vice president of CF&I Bowers wrote that they were able to secure "the cooperation of all the bankers of the city," who agreed to lend Colorado "all funds necessary to maintain the militia and afford ample protection so our miners could return to work," per "Failure to Quit" by Howard Zinn. It's estimated that CF&I paid the National Guard up to $80,000.

Although the striking workers and their families greeted the arriving National Guard with an American flag, thinking that they were here to protect the striking workers, the National Guard soon joined the private militia in beating and jailing striking workers. Over the winter, the National Guard made 172 arrests and at least one striker died while in custody after being forced to sleep on a cold cement floor for 25 days. Countless others were abused and tortured.

The Ludlow Massacre

As funds started to run out during the spring, Governor Ammons recalled most of the National Guard troops in early April. However, two groups of troops remained, under the command of Major Pat Hamrock and Lieutenant Linderfelt, stationed on a ridge overlooking the Ludlow tent colony. According to "The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders," Hamrock reportedly ordered Linderfelt to investigate an anonymous tip they'd received about a nonunion miner being held by striking workers in the Ludlow tent colony. As they went to investigate, the machine gun on the ridge was also aimed at the Ludlow colony.

Although it's unclear who fired the first shots, by 9AM on April 20, 1914, two dynamite bombs had gone off and the machine gun was firing wildly into the colony. And according to "The Zinn Reader," the striking workers were incredibly outmatched. While the machine gun fired "thousands and thousands of shots," there were at most 50 guns within the Ludlow tent colony, including shotguns. While many escaped under the rain of gunfire, others hid in pits under the tents.

After gunfire ceased and the sun set, the National Guardsmen set fire to Ludlow colony and shot those who tried to flee the flames, writes The New Yorker. Those who had tried to find safety under the tents ended up dying from asphyxiation. It's estimated that up to 77 people died during the massacre, though this estimate is likely on the conservative side.

Battling for 10 days

As news of the Ludlow massacre spread to the other tent colonies, the striking workers launched an offensive against the coal operators. After funerals were held for the dead, UMWA officials issued a "Call to Arms," that called workers to "organize the men in your community in companies of volunteers to protect the workers of Colorado against the murder and cremation of men, women, and children by armed assassins in the employ of coal corporations, serving under the guise of state militiamen," per History Matters.

In "The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders," Laurie and Cole write that over the course of 10 days, hundreds of striking miners, company guards, and state troops battled in several towns, including Forbes, Aguilar, and Black Hills. The mines in Berwind and McNally were seized by striking workers and those in Aguilar and Walsenburg were "completely torched," according to Timeline.

According to Legends of America, although the exact number of casualties is unknown, it's estimated that at least 30 people died and 40 were injured during the 10 days of battles, making the Colorado Coalfield War "the deadliest strike in the history of the United States" as of 2021.

Wilson deploys federal troops

On April 29, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson decided to send federal troops into Colorado to control the strike. Two days later, roughly 1,600 soldiers arrived in Trinidad, where they "disarmed all civilians, including deputy sheriffs," according to Legends of America. Zinn writes in "The Zinn Reader" that over the following seven months, negotiations to end the strike continued but the coal operators refused to settle. However, by December 1914 the UMWA had run out of money and they were forced to call off the strike and admit defeat.

Up to 400 striking workers were subsequently charged with "murder, property destruction, and conspiracy to restrict trade." However, most of the charges ended up being dismissed or being overturned on appeal. 22 National Guardsmen were also court-martialed for their participation in the massacre, but according to CPR, "all but one were acquitted." Linderfelt was found guilty of assault for hitting Louis Tikas with his rifle so hard that it broke the rifle stock. After being found guilty, Linderfelt was given "a light reprimand," despite having also ordered for Tikas' execution.

President Wilson also assembled the Commission on Industrial Relations, which found that Rockefeller, Jr. was the leader of the coal operators' policies. The Commission also described the strike as "a revolt by whole communities against arbitrary, economic, political, and social domination by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company and the smaller coal mining companies that followed its lead."

Legacy of the strike

Although the striking workers ultimately lost, the public revelation that CF&I was undoubtedly subjecting its workers to economic and political domination forced Rockefeller Jr. to make some changes. Although Rockefeller Jr. was unwilling to accept the UMWA as the workers' representation, Legends of America writes that he started coming up with his own labor-management plan. Known as the Employee Representation Plan, or the Rockefeller Plan, this policy gave workers the right to collective bargaining through elected representatives as well as the ability to "participate in annual conferences with management." Since the UMWA had been defeated in the strike, 84% of voting workers agreed to the Rockefeller Plan in 1915.

Critics described the plan as "company unionism," created solely to limit the influence of unions. And according to "Nonunion Employee Representation" by Bruce E. Kaufman and Daphne Gottlieb Taras, many "complained about their powerlessness."

In the end, the Rockefeller Plan "had a greater impact on management than on labor." By opening up a channel of communication between workers and management, supervisors were forced to address the grievances of workers because now they could no longer be completely ignored. Rockefeller Jr. soon went on to install this plan into other companies of his, including Standard Oil. But in December 1933, the Rockefeller Plan was ultimately rejected by CF&I workers in favor of a contract with UMWA.