Proposed States In The U.S. That Never Happened

For the majority of Americans alive today, the idea of 50 states might seem immutable. It is a nice round number that has not changed since 1959. Any thought of changing the number, especially to an odd one, appears unsettling. But in the America of the 2020s, the issue of partitioning existing states or adding new ones has gained considerable traction as political tensions between the left and right wings rise.

While these movements can be a bit shocking to those used to the 50 states, they are nothing new. American history is full of attempts to partition and create new states out of existing ones, many of which ended up failing. From the State of Franklin to Deseret and beyond, numerous movements have petitioned Congress for statehood along geographic, cultural, racial, and political lines. Some of them continue to be debated to this day. Below are some of the most famous proposed states that failed to receive admittance, along with some currently pushing for recognition that might still get their chance.

Westsylvania/Vandalia

According to the Journal of the American Revolution, there exists an oft-used but poorly understood term in American historiography called the "14th colony." Although it is defined as a colony that did not revolt against British rule, the term is incorrectly used to describe at least eight different entities. One of these, however, did request this title — the short-lived colony of Westsylvania.

A group of speculators led by Benjamin Franklin founded the Vandalia Company to colonize Western Pennsylvania's Ohio River Valley. The settlement eventually would extend into Kentucky and West Virginia. In 1772, King George III's Privy Council chartered the Colony of Vandalia, named in honor of British Queen Charlotte's alleged Vandal ancestors. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775 put the project on the backburner.

The inhabitants of Vandalia did not give up their aspirations for independence. Pennsylvania and Virginia both had territorial designs on the area. Vandalia's inhabitants, however, were independence-minded. In 1775-76, they issued a petition for a state called Westsylvania. The petition noted that Richmond and Philadelphia were too far away to effectively govern the Ohio Valley frontier. Their malfeasance and lack of interest in the area had led to a slew of abuses enumerated in Westsylvania's independence declaration. Thus, they requested to be admitted as a "Sister Colony & the fourteenth Province of the American Confederacy." The Founding Fathers ignored it, distracted by war, and Virginia and Pennsylvania split the former colony among themselves.

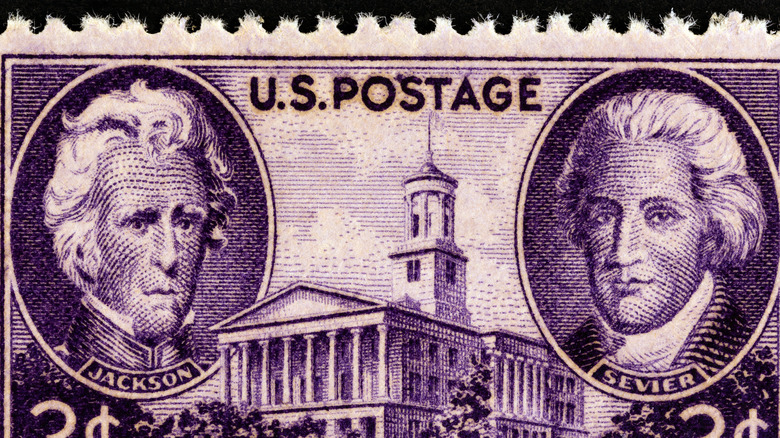

Franklin

The original 13 states all laid claims to frontier lands, resulting in a series of messy land disputes. To solve this issue, states often ceded the land to the Confederation Congress (the government under the Articles of Confederation) to organize into new territories and states. In early-1780's North Carolina, a farcical set of events thwarted a hardy frontiersman's attempt to create the State of Franklin.

The state sought to unload a group of politically and geographically detached western counties. But the state legislators were keen to profit first. The Land Grab Act of 1783 placed North Carolina's western lands for sale, and the legislators bought them up. The entire deal, of course, was of questionable legality. Then the territory was ceded to Congress with the expectation that it would honor the deals. Following the cession, the inhabitants of the ceded lands feared Congress would sell the land as war debt repayment. The locals preemptively created the State of Franklin in 1784 under Revolutionary War veteran John Sevier (pictured above). The state's radical constitution included near-full male suffrage but banned doctors, lawyers, and clergy from politics.

Meanwhile, North Carolina had voted to nullify the cession, so the U.S. government intervened to end the quarrel. Congress rejected Sevier's petition for Franklin's statehood, forcing him and his followers to rejoin North Carolina in 1789. The state then promptly ceded the lands back to Congress to create a new territory. It ended well for Sevier, however. He became governor of the newly minted State of Tennessee.

Deseret

The Church of Latter-Day Saints emerged from the religious ferment of the Second Great Awakening. After their expulsion from Nauvoo, Illinois, and the murder of their founder Joseph Smith, the group colloquially known as Mormons migrated west into what was then part of Mexico under Smith's successor Brigham Young. According to an observer published in the American Catholic Quarterly Review, "Brigham Young was king" of the theocratic State of Deseret, as both the civil head and president of the church. Non-Mormons, including Catholics, were allowed some freedom of worship. But in 1848, the Mormons returned to American sovereignty after Mexico ceded its northwestern territories under the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. The once-isolated Mormon settlements, which had wanted to be left alone, were drawn into the greater American economy and came to the attention of the federal government in Washington.

Young realized that the future lay with the United States and petitioned Congress to make Deseret a territory. Young hoped that the Territory of Deseret would include Southern California, giving Deseret maritime access. Simultaneously, Young and his advisors hastily drafted a constitution and petitioned for Deseret's statehood. Unsurprisingly, Congress rejected that petition but accepted Young's territory proposal — with some changes. Deseret renounced all claims to California and rebaptized itself "Utah" after the Native American Ute tribe. However, it retained the modern state of Nevada, so Young accepted the conditions and dissolved the State of Deseret in 1851, becoming Utah's first governor. Several subsequent attempts to reconstitute Deseret during periods of Mormon-federal hostility failed, and Utah became a state in 1896.

Sequoyah

Although most proposals originated among European and American settlers, a group of Native American tribes sought to obtain their own star on Old Glory in 1905. Modern-day Oklahoma was essentially (and sadly) the federal government's dumping ground for deported Native American tribes. The eastern portion formed a distinct legal entity called Indian Territory whose inhabitants were permitted self-rule. The 1898 Curtis Act, however, stipulated Indian Territory's dissolution by 1906. Alarmed at the prospect of losing their independence and possibly their tribal identities, the Five Civilized Tribes, led by the Cherokee, settled on statehood. The new state would be called Sequoyah after the creator of the Cherokee Syllabary. Unlike most other states, it had a Native American majority. The Five Tribes drafted a state constitution in 1905 that a supermajority of participating voters ratified (albeit among low turnout).

After ratification, the bill for statehood went before the 59th Congress in 1906. The records of the 59th Congress indicate Republican opposition to the bill. Congressman Bird McGuire (R-OK) argued that uniting Oklahoma Territory with Indian Territory would force whites and indigenous people together and pressure the latter to conform to the former, thereby accelerating assimilation. Sequoyah's statehood was seen as a bid to block assimilation by giving the tribes their own state.

While racism absolutely played a role, there were also more immediate political concerns. The Republican Party sought to block the addition of a Democrat-majority state. They ultimately carried the day. The 1906 Enabling Act merged Indian Territory with Oklahoma Territory. The following year, Oklahoma became a state.

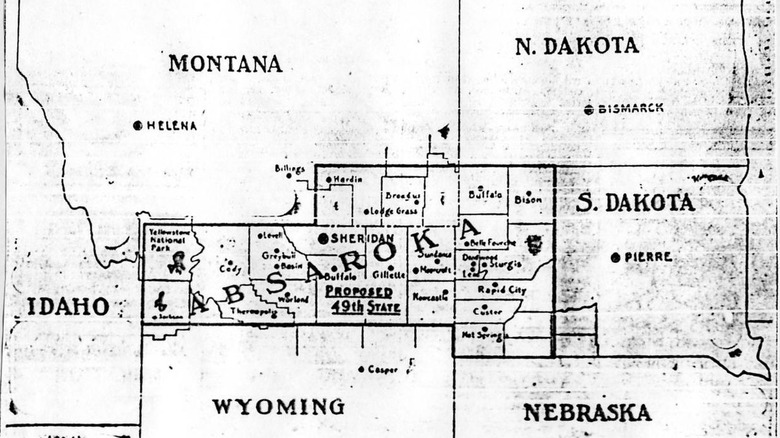

Absaroka

President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal was a relief program meant to attenuate the devastating economic effects of the Great Depression. However, not everyone benefited or wished to take part. According to South Dakota Magazine, farmers in that state were left out, despite years of drought.

Meanwhile, in Wyoming, FDR Democrats swept to power in the state capital of Cheyenne. Upstate Wyoming, a Republican stronghold, had its interests relegated to the backburner since Wyoming's Democratic Party represented railroad and oil interests in the south of the state. Tensions between the small rural communities in Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming and the larger towns in the states were exacerbated by the uneven spread of New Deal aid, leading to a full-blown movement for secession.

Under the leadership of former baseball player A.R. Swickard, Absaroka came into being in 1939. The fledgling state obtained some trappings of statehood. It issued its own license plates, had a Miss Absaroka beauty queen, and hosted King Haakon VII of Norway on a "state visit." The town of Sheridan, Wyoming, became the state capital. But in the end, it did not get far. The outbreak of the Second World War put a damper on the movement, while Wyoming in particular placated the secessionists with concessions. Today the movement is considered a joke of sorts, although the secessionists were serious about moving it forward.

Washington, D.C.

On April 22nd, 2021, the Democrat-majority House of Representatives passed the Washington, D.C. Admission Act. Its proponents hailed the bill as giving the citizens of Washington, D.C., full representation within the U.S. government. Since D.C. residents pay taxes, they should have the same representation as other U.S. citizens, as the Founding Fathers' famous rallying cry points out.

However, Republican lawmakers have accused the Democrats of a naked power grab to gain additional Senate seats to push through their chosen policies. But D.C. statehood faces the major hurdle of the U.S. Constitution, and currently your view on how constitutional a State of D.C. would be depends on which side of the aisle you fall on.

Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, argued for the constitutionality of D.C. statehood in The Washington Post, writing, "There are no good legal arguments against it." Texas attorney general Ken Paxton, on the other hand, believes that Article I, section 8, clause 17 of the U.S. Constitution explicitly empowers Congress "to exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District." The word "District" here refers to the nation's capital, which would become Washington, D.C., in 1791. Thus, it's his opinion that D.C. statehood would require a constitutional amendment, and conveniently for Republicans like himself, in the current political climate, the chances of mustering the required ⅔ majority to amend the constitution are basically zero.

Superior/Ontonagon

In 1858, the NY Times (via Mackinac Journal) reported that Michigan and Wisconsin were finalizing the creation of the State of Ontonagon in Michigan's Upper Peninsula (UP). Although it, along with subsequent late-19th-century attempts for UP statehood, failed, it highlighted the economic, political, and cultural differences between the UP (whose inhabitants are known as Yoopers) and the rest of Michigan. The UP has frequently complained of a lack of representation and control over its tax dollars, and sympathy for secession remains to this day.

The differences between Lower and sparsely populated Upper Michigan are stark. The UP has its own Finnish-influenced dialect and its own separate history from the rest of the state. Yet secession attempts have consistently gone nowhere. The latest one in the mid-1980s only garnered 20,000 signatures out of a required 36,000 to even get on the ballot.

But the possibility of a "State of Superior" could rise again thanks to recent political changes. The Washington, D.C. Admission Act has proposed making Washington, D.C., a state, which would give the Democratic Party two more guaranteed Senate seats. However, the Wisconsin State Journal has noted that Republicans would expect concessions in return, namely a state of their own to balance D.C.'s new senators. Thus, the State of Superior could be the key to solving the question of D.C. statehood and preserving a balance of power in Congress. For Superior's proponents, it is a golden opportunity.

Jefferson

The State of Jefferson is an ongoing attempt to detach the rural regions of Northern California and Southern Oregon from their respective states. According to the University of Oregon's Jefferson Public Radio, the poor state of the area's highways and roads hampered economic development and caused resentment among the locals towards their state governments. Thus, in 1941, a group of armed secessionists rose up "in patriotic rebellion" and elected John Childs as governor of their new state.

Jefferson issued an independence declaration, which accused both California and Oregon of neglecting the region's vital copper mining industry. Armed militias set up checkpoints and collected tolls from travelers, in defiance of California State Police attempts to disarm them. Interestingly, though, Jefferson would only be in rebellion every Thursday, making it more of an armed protest rather than an outright secession movement. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the movement faded as the country unified behind the war effort.

Greater Idaho

Another partition campaign in the Pacific Northwest aims to create the State of Greater Idaho. As of 2025, 13 Oregon counties have voted in favor of seceding and joining Idaho. Their motivation? Differences in politics, culture, and money all play a role.

The counties in question are all heavily Republican in a Democratic state whose politics are dominated by the densely populated urban centers of Portland and Salem. Their grievances include perceived neglect by Oregon's Democratic state government, which they feel does not represent their interests. The COVID-19 crisis further exacerbated tensions. Some felt that Governor Kate Brown's issuing of a vaccine mandate threatened to devastate Oregon's rural healthcare system if staff walked off the job rather than get vaccinated. Idaho, on the other hand, offered lower taxes, less regulation, few gun restrictions, and some counties where COVID vaccine mandates were illegal.

In order to happen, Oregon, Idaho, California (should the north join), and Congress would need to approve the measure. The Greater Idaho Movement has noted that the plan neither creates a new state nor affects the Senate's balance of power, points they believe are in their favor. They also believe California and Oregon would lose little from ceding these less-populated areas.

Chicago/Cook County

In 2010, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Pat Quinn was elected governor of Illinois. Quinn accomplished this with merely three counties, including the deep-blue Cook County and the City of Chicago. Quinn's victory highlighted the tensions between the densely populated Democrat fortress of Chicagoland and the rural Republican counties of downstate Illinois that feel politically disenfranchised at the state level. The Illinois GOP's proposed solution? Kick Chicago out of Illinois.

Proponents of the New Illinois Movement have a laundry list of grievances against Chicago. Chicago Magazine notes that Illinois taxpayers have repeatedly been on the hook for Chicago's fiscal mismanagement, while the city's strict gun laws influence statewide gun policy toward greater restrictions. In contrast, many downstate counties have declared themselves Second Amendment sanctuaries that do not enforce state or federal gun restrictions. These are just two issues among a plethora of others the movement lists. Basically, downstate Illinois sees itself as another world from Chicago.

However, opponents of partition note that downstate Illinois receives more money than it pays into the state coffers in taxes, which would be a problem for it if the split actually happened. Thus, Chicago Magazine notes that splitting the state might be a good compromise. Chicago would retain more money, and downstate could preserve its cultural separateness. In today's America, such a solution is not outside the realm of possibility.

Puerto Rico

In 2020, 55% of Puerto Ricans voted in a non-binding referendum on statehood, with 53% of those who voted supporting statehood. But the result was far from a resounding endorsement. The question of statehood for this U.S. territory spans a complex series of cultural and financial issues that make the island's road to statehood rockier than just a simple vote of Congress.

Despite support for statehood, it is unlikely to happen anytime soon because enough Puerto Ricans and other Americans alike do not support it. While there are financial considerations, the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation pinpointed the main divide as cultural back in a 1997 comment on H.R. 856. Puerto Rican statehood would require the language of government and education to default to English. But Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico's culture descends from a mix of Spanish and indigenous Taino influences. Puerto Ricans generally have no interest in replacing Spanish with English. According to the left-leaning Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Puerto Ricans rightly fear that their Hispanic culture will be trampled underfoot by American mass media.

But ultimately, economic considerations may prevail. If the economic benefits of statehood outweigh the cultural and linguistic costs, Puerto Ricans may still vote to join the United States as a state if given the opportunity. Only time will tell.

Yucatan

The easternmost portion of Mexico, which sits along the trade-and-travel-heavy Gulf of Mexico, is the Yucatan Peninsula. Around 1845, with European colonialism on its last legs in North America, members of President James K. Polk's administration were concerned that a foreign armada might stage a blockade of the Gulf of Mexico and prevent American shipping traffic. At that point, the Republic of Yucatan was its own country, and when the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846 in Texas — Mexico and the U.S. fought over control of the region — the peninsula stayed neutral. Then the U.S. Navy blockaded the Gulf of Mexico, prompting leaders from the Yucatan to send an envoy of negotiators to Washington, D.C. They sought defensive assistance from the U.S., as well as recognition of its independence. The ruling class of the Yucatan was willing to give up its neutrality even, proposing that the U.S. admit the peninsula as a state.

President Polk, keen on U.S. expansion — which was the whole point of the Mexican-American War — pushed into the House of Representatives a bill that began the legal framework for the state of Yucatan. The U.S. Senate, concerned that annexation would continue the Mexican-American War, killed the legislation in 1847. A year later, the war would end and the Yucatan would become part of Mexico.

South Jersey

New Jersey is one of the smallest states in terms of area, but it's nonetheless quite varied in its terrain and atmosphere. The northern part of the state is urban, metropolitan, and densely populated, situated very close to both New York City and Philadelphia. The western and southern parts of New Jersey are full of the wilds, hills, and green-spaces that must have inspired the official New Jersey nickname of "the Garden State." That tension between city and country is deeply entrenched in New Jersey, which in the 1600s was separated into two sections, one bucolic and populated by adherents of the Quaker faith, and the other more city-oriented and Puritan-controlled.

Even after those two places became one, and New Jersey became one of the original U.S. states, a schism was always a threat. In the 1970s, political leaders in the southern part of the state began a secession drive, which would've declared all lands below Interstate 195 and the Manasquan River to be South Jersey. The idea got as far as the 1980 election, when voters in five of six affected counties approved a referendum calling for the split. A call for new statehood continued into 1981, the same year that Thomas H. Kean was elected governor, and he didn't wish to push the matter forward.

New York City

With a population of more than 8 million people, New York City is by far the largest city in the United States, and is home to more Americans than most of the 50 states. The Big Apple is its own thing, dense with culture and its own sensibility, and it's all distinctively different from that of the rest of the state of New York. New York City is such a world unto itself, with the residents paying most of the taxes that support the entire state, that as early as 1861, there was talk of elevating the five associated boroughs (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Queens, and the Bronx) to statehood.

By 1969, statehood for New York City was a political issue. Author Norman Mailer mounted a campaign for the mayorship of New York City with what was primarily a single-issue platform, that New York City should be a state. The residents of the metropolitan community seemed to have little interest in pulling away from the rest of the state, however — otherwise, Mailer might have gotten more than 5% of the vote. That sent a message to the powers that be, that New Yorkers seemed fine with keeping things the way they were.

Taiwan

China asserted its power over Taiwan in the early 1970s, attesting that the island nation was a Chinese territory and refusing its claim of independence. The world community, led by the United States, sided with the powerful communist government of China, acknowledged Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan, and gave China Taiwan's spot in the United Nations.

The goal of the alliance with China, as crafted by President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, was to intimidate the Soviet Union, the U.S.'s Cold War rival. Over the decades, China has enforced rule on Taiwan more and more, and fearing a full takeover, Taiwanese-American activist David Chou created the 51 Club and FormUSA Foundation in the 1990s. The aim of both organizations: Protect Taiwan from China by making it the 51st state in the United States. The U.S. annexing Taiwan would likely lead to an international incident, and as such, no government officials acted on Chou's suggestion.

Sicily

In 1943, the 21-year rule of Italy by fascist dictator Benito Mussolini came to an end, and in 1945, World War II concluded with the Axis Powers (including Italy) defeated. This left the country upended and in a kind of political limbo. Many residents of Sicily, a formerly sovereign island violently annexed into Italy in 1860, thought it looked like the ideal time to go independent once again, or to at least align with a different powerful nation.

Allied Forces liberated and then occupied Sicily with the 1943 military drive known as Operation Husky. For the remainder of World War II and into the post-war reconstruction period, Sicily housed the major U.S. Navy base Sigonella. More than 4,000 Americans lived and worked on the island, and a Sicilian-American economy and culture quickly developed. Salvatore Giuliano, a big player in the Sicilian organized crime syndicate (which flourished in the U.S. at the same time) wanted to make the arrangement more official, and in 1947, he wrote a letter to U.S. President Harry Truman asking him to annex Italy and to fast-track statehood.

Antonio di Stephano, head of Sicily's Party of Reconstruction, took up the cause at home, using the Statue of Liberty on official papers and reaching out to the U.S. government to discuss joining up. Sicily would've been the first remote, non-contiguous state in the union but for Truman already considering another region in that model: He made Alaska the 49th state instead.

North Slope

The uppermost portion of the Alaskan mainland is an administrative district historically and logically referred to by locals as the "North Slope." Distant from all of Alaska's largest cities, its main population center of Utquiagvik, formerly known as Barrow, is the most northerly settlement in the United States. In other words, North Slope is remote, and the influence of ancient and indigenous cultures, the Inupiat and Yupik, resonate into the contemporary age. When an early 1990s state supreme court ruling banned traditional hunting and fishing methods, rulers from those communities discussed separating from the rest of Alaska. They held some clout, too, as northern Alaska is home to lucrative oil reserves that provide income for every resident of the state.

The movement to create what would've been the most distant and least-populated state in the United States didn't gain much traction. The hunting ban and oil profit sharing laws remained in effect across Alaska.

West Kansas

In early 1992, the Kansas State Legislature passed into law new rules for funding public schools. Opponents of the law felt it would lead to an egregious hike of property taxes while also denying oversight on a county level and decreasing per-student spending in rural areas.

The opposition in the westernmost part of the state, barely populated farmland and natural gas fields, felt so overlooked and at odds with lawmakers that a movement to make West Kansas its own state gathered substantial support. Led by attorney Don Concannon, the contingent preemptively met in the town of Ulysses to figure out the exact borders and decide that the pheasant ought to be the state bird of West Kansas, and the yucca the official state flower. When put to voters, nine counties in the southwest corner of Kansas approved secession, but that didn't matter after the state attorney general said that the idea violated Kansas' state constitution.

Albania

For the last century, the European nation of Albania has unabashedly appreciated the United States. After it declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, President Woodrow Wilson officially recognized the new nation, had it admitted into the League of Nations, and kept it intact amidst post-World War I border re-draws. When President Bill Clinton bombed Serbia, it was perceived as an act of helping ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. Albanians showed their thanks with a sharp rise in babies born in the 1990s with the names Bill and Hillary (after the Clintons), and when former Secretary of State James Baker visited the country around that time, he was greeted by cheering crowds.

In the early 1990s, with pro-American sentiment at a notable peak, the federal government discussed putting a vote to the people. A referendum was in the works to approve asking the United States to annex Albania with the eventual goal of making the country that's slightly larger than the fiftieth state, Hawaii, into state number 51. The idea never got past the planning stage.

Transylvania

Nine North Carolina businessmen, led by Richard Henderson, created the Transylvania Company in 1774 to develop hospitable lands west of the established American colonies that lined the East Coast. In March 1775, the organization purchased from the Cherokee large swaths of land that would later comprise Kentucky and Tennessee. Henderson hired explorer and frontiersman Daniel Boone to lead a group of 30 settlers to establish a colony called Transylvania and numerous settlements, including Boonesborough, situated on the banks of the Kentucky River.

The Transylvania Company considered Transylvania to be the 14th colony, and it would've entered the United States as the 14th state, about to form after the American Revolution of the 1770s. The other colonial, then state, governments in the region wouldn't recognize Transylvania as anything beyond a bunch of rogues. Virginia and North Carolina's governments questioned the legitimacy of the Cherokee land purchase, and the Virginia legislature legally invalidated it all by declaring that land to be Kentucky County.

Newfoundland

There are 10 provinces that make up the nation of Canada, and the last one to join the confederation was Newfoundland and Labrador in 1949. A British colony until the rest of Canada formed in the 19th century, Newfoundland operated as a self-governing small country until the mid-1930s. With the conventional wisdom holding that in the post-World War II years, it would make political and economic sense to join a much larger nation, the residents of Newfoundland voted themselves into Canada via a referendum in 1948. Just a year earlier, various polls held in the region found that 80% of Newfoundlanders favored joining the United States.

The attraction, however, wasn't mutual. The United States federal government didn't approach anyone about Newfoundland becoming what would've been the 49th state at the time, because acquiring the area offered little in the way of strategic value. The only major figure in the U.S. who latched on to Newfoundland's push for statehood was Chicago Tribune owner Robert McCormick, who published multiple supportive editorials that failed to be very persuasive.

Texlahoma

Geographic features, particularly the Red River, played a part in establishing the borders of the oddly shaped states of Texas and Oklahoma. Both states feature rectangular regions that are each hundreds of miles away from their respective population centers. Texas' northern square and Oklahoma's far-west strip are both called "panhandles," and in the 1920s, the leaders and citizenry in both spots believed they were being overlooked by their state governments and thus missing out on the funding, attention, and benefits happening in the more densely populated zones. As Americans zoomed into the automobile age, those places couldn't get anybody to build them roads.

The solution: team up to make their own government. Oklahoma politician A.P. Sights drew up a plan for 46 Texas counties and 23 Oklahoma counties to form the state of Texlahoma. When former Texas congressional representative John Nance Garner IV became vice president under Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, he championed the Texlahoma plan. The general public was harder to convince. Researchers at the time realized the plan was doomed to fail because it couldn't get enough Texans to renounce their status as Texans.

The Free and Independent State of Scott

The Civil War got underway when 11 states seceded from the U.S. to form the Confederate States of America, where slavery could remain a legal practice. The last state to leave the Union was Tennessee, because the eastern area was adamantly opposed to the exit. Not everyone in the South wanted to form a new nation — that was the position of wealthy plantation owners who relied on slave labor to make their money. The middle class wasn't necessarily on board, and a group of politicians from multiple Tennessee counties attempted to pass a legal resolution to declare a new state that would stay in the U.S. After it failed, representatives from Scott County refused to give up and instead declared itself the Free and Independent State of Scott, bolstered by a vote tally of 97% of its residents opposing secession.

Any declaration of independence, or new statehood, is apparently only valid if the dominant group takes notice. The Tennessee state government refused to accept or even acknowledge the Free and Independent State of Scott, and that part of Tennessee remained with the state through the Civil War and after. In 1986, on the 125th anniversary of the statehood proclamation, the Free and Independent State of Scott was ceremonially but formally brought back into the U.S.

Long Island

The American recession of the late 2000s left state and local governments strapped for cash, particularly those in New York City and New York state. Officials issued higher taxes and fees while also cutting back on services, making the economic crisis even worse for those already financially impacted. Citizens and politicians from the New York City area of Long Island took particular objection with a $1.5 billion payroll tax that would save the insecure Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York City's subway and bus system. That move stood to benefit the rest of the city far more than it would Long Island, and the idea caught on that a more localized government in touch with the populace would be a more preferable arrangement. In May 2009, the Suffolk County Legislature voted 12 to 6 in favor of a study and then a referendum that would allow Long Island to secede from the rest of New York.

Not counting sections of the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, Long Island is occupied mostly by two counties: Suffolk and Nassau. While Suffolk County officials were eager to embrace home-rule, Nassau's leaders had no interest. Without the support of Long Island's other major county, the idea couldn't advance to the New York state legislature, which would be the first step in establishing a breakaway state.

Nickajack

The Nickajack Expedition of 1794 resulted in the American expulsion of the Cherokee Nation from the Tennessee River Valley, allowing for settlement and expansion of the U.S. into the region. Across the 19th century, the area — northern Alabama and eastern Tennessee — became economically impoverished because the land wasn't suitable to grow many cash crops, and so it wasn't a place where plantations dependent on slave labor developed. When the Civil War loomed, that section of Appalachia largely opposed taking up arms to protect slavery, and didn't agree with the decisions of Alabama and Tennessee to secede and join the Confederacy. On July 4, 1861, 2,500 protesters in Winston County declared themselves to be residents of the new and Union-loyal Free State of Winston. Nearby counties joined in, and Winston quickly evolved into the larger state of Nickajack.

A newly established state needs assertive advocacy from its leaders, particularly during such politically tumultuous times that involved secession and civil war. The collective-minded people of Nickajack couldn't determine who their leadership might be, and the movement died down. Also not helping: the governments of Alabama and Tennessee wouldn't acknowledge the anti-slavery communities within its borders.