These Were The Best Movies Of 1922

As noted by trade publication Wid's Year Book 1921, by the end of that year, the Hollywood film industry was suffering a bit, as it grappled with a postwar slump at the box office and growing competition from overseas. Despite the cinematic triumphs of Charlie Chaplin's "The Kid" and Rudolph Valentino's "The Sheik," theater owners in 1921 had faced a glut of "bad" movies and tepid ticket sales. An influx of prestige foreign films, including Germany's "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," as well as threats of censorship also had exhibitors sweating. However, in their speculations for the 1922 film market, many Wid's of contributors predicted that theaters would see a return to "normal," with more high-grossing, quality American pictures and fewer big-screen duds.

As it turned out, 1922 was a pretty good year for Hollywood movies. In December, Wid's Film Year Book 1922-1923 issued a mostly positive assessment of the industry, and its annual list of the top 10 films, as voted on by critics from around the country, reflected the optimism. (One of the list's films, "Tol'able David," opened in November of the previous year and is generally considered a 1921 release.) In the years before the Academy Awards, making the Wid's list was a prestigious distinction for filmmakers. And not unlike a typical roster of Oscar Best Picture nominees, the 1922 list includes a number of opulent costume dramas, ballyhooed releases by distinguished directors, star vehicles, groundbreaking novelties, a happy little comedy, and no foreign productions.

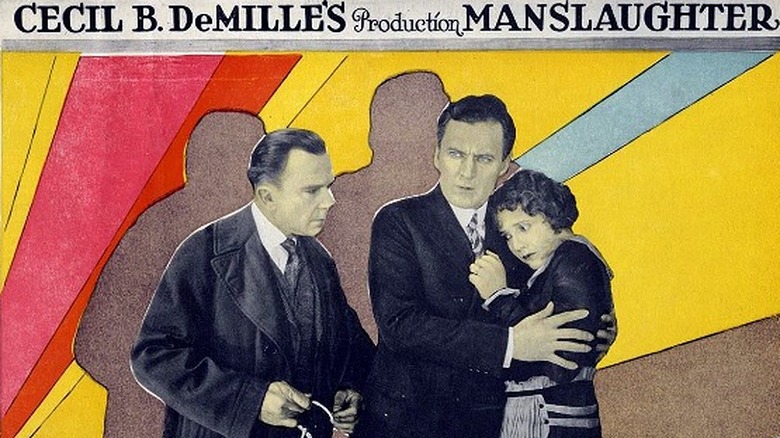

Manslaughter

Directed by movie titan Cecil B. DeMille and starring Leatrice Joy, "Manslaughter" received many glowing reviews from America's critics and, according to "Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood," was a major hit at the box office as well. Based on an Alice Duer Miller novel and written by DeMille's frequent collaborator Jeanie Macpherson, the contemporary melodrama tells the story of spoiled society girl Lydia Thorne, whose indulgent recklessness leads to a policeman's death and her incarceration for manslaughter. Lydia's life-altering prison experience is then put to the test when she is faced with the drunken dissipation of her lawyer boyfriend, played by Thomas Meighan.

Photoplay called "Manslaughter" an "admirable commentary on rich, rushing, headstrong Young America," and one of DeMille's best. Moving Picture World described the film as the director's "finest achievement," praising him for presenting a "gripping story" in a "forceful manner" and embellishing it with his "characteristic touches" of "gorgeousness and splendor."

As with many big productions, "Manslaughter" enjoyed a robust publicity campaign from its studio, Paramount. As a pre-production stunt, according to "Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood," Macpherson conspired with a friend in Detroit to steal a fur piece, then got arrested for theft under a pseudonym. The writer spent three days in a real jail. Then Joy, doing her own "research," according to Photoplay, arranged to be arrested and jailed in Los Angeles, and her mug shots were released to the press. If the film's hearty ticket sales were any indication, these PR ploys did their job splendidly.

Oliver Twist

As noted by the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, by the time the 1922 adaptation of "Oliver Twist" had come along, six other screen versions of Charles Dickens' novel had already been filmed. The 1838 tale about an orphan boy who escapes a workhouse to become an undertaker's apprentice and junior pickpocket had perennial audience appeal. What made the 1922 version stand out were its stars – Jackie Coogan in the title role and Lon Chaney as Fagin, leader of the pickpocket gang. The 8-year-old Coogan had starred with Charlie Chaplin in "The Kid" and was the most popular child actor in Hollywood, according to Britannica. In 1922, Chaney had not yet earned his sobriquet "The Man of a Thousand Faces," but as noted by PBS, was well known to screen audiences as a compelling character actor.

Frank Lloyd, who brought Dickens' "A Tale of Two Cities" to the screen in 1917, directed and wrote the script for the 1922 "Oliver Twist." The veteran helmer earned praise from The New York Times for his mostly-faithful adaptation and his refusal to use Coogan for cheap laughs. The same review called Coogan's portrayal of the orphan Twist "a characterization you cannot resist and have no desire to." Life also gushed about Coogan's performance, describing the young actor as an incredible, natural artist. After expressing appreciation for Lloyd's "intelligent" direction, Life then declared the film "one of the few really great pictures of this or any other year."

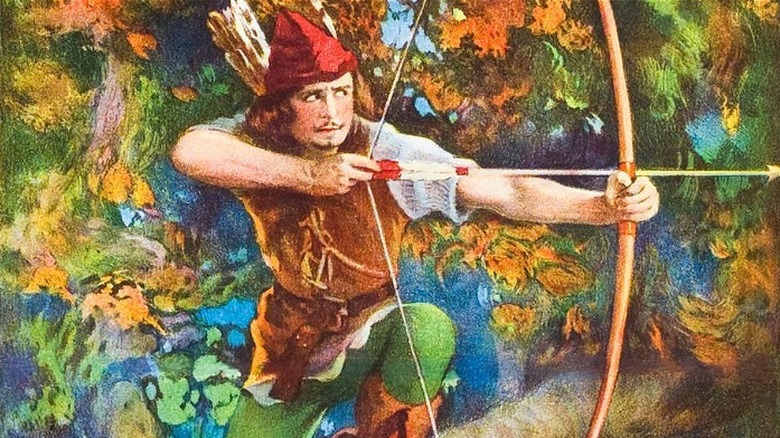

Robin Hood

"He robs from the rich and gives to the poor!" In 1922, moviegoers and critics alike delighted in Douglas Fairbanks' portrayal of the legendary bandit in "Robin Hood." As noted by Britannica, by the time Fairbanks' production company was undertaking "Robin Hood," which was directed by his frequent collaborator Allan Dwan, his athletic performances in "The Mark of Zorro" and "The Three Musketeers" had cemented his reputation as Hollywood's swashbuckling king. Fairbanks not only played the title role, he also wrote the screen story, molding the hero in his own image. In his version, the story of the Crusades-fighting English earl who transforms into Robin Hood to save the throne from evil Prince John is told in two distinct parts, with two distinct characterizations.

The New York Herald raved that "Robin Hood" marked the "high water mark of film production – the farthest step that the silent drama has ever taken along the highroad of art." Fairbanks' performance as the earl, according to the Herald, is "dignified, erect, and utterly fearless," while his Robin Hood "climbs up castle walls, leaps over moats, and slides down tapestries." Photoplay commended the film as a "glorious three-ring circus with something doing in every ring." As tallied by IMDb, in addition to garnering glowing reviews, "Robin Hood" became the top-grossing film of the year. It also marked the debut presentation of the iconic Grauman's Egyptian Theatre, the first big-screen venue of Hollywood proper, according to Cinema Treasures.

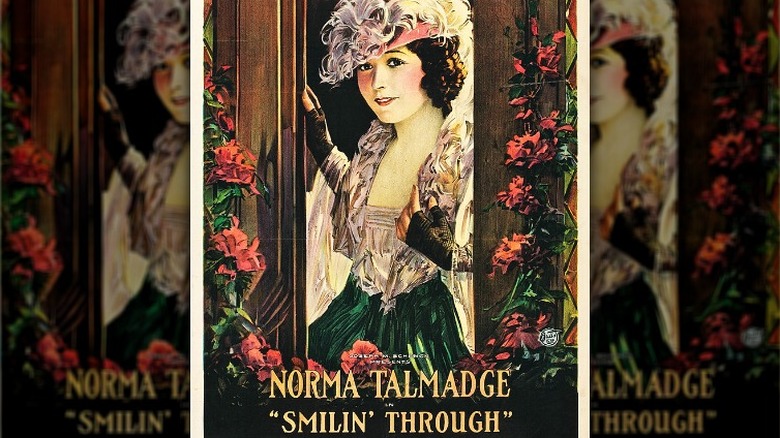

Smilin' Through

Based on a 1919 Broadway show by Jane Murfin and actress Jane Cowl (under the pseudonym Allan Langdon Martin, according to Encyclopedia), "Smilin' Through" was directed by Sidney A. Franklin and starred the popular Norma Talmadge and the original Harrison Ford in double roles. Told partially in flashback, the melodrama begins with the wedding day death of bride Moonyean, who is killed when her former suitor, Jeremiah, shoots at groom John but accidentally kills Moonyean instead. The story then jumps ahead 20 years to the day that Kathleen, John's niece and Moonyean lookalike, declares her intention to marry Jeremiah's son, Kenneth. The unforgiving John opposes the marriage, however, and seemingly doomed, the lovers separate.

In its thumbs-up review, Variety (via The Norma Talmadge Website) succinctly listed the film's virtues: "'Smilin' Through' displays expert direction. The punches are landed effectively. A capable cast works up the big points..." Film Daily noted that ever since Talmadge's producer husband Joseph M. Schenck had paid a whopping $75,000 for the film rights to the hit play, "Smilin' Through" had been touted in the trades as one of the "big ones." Affirming its greatness, Film Daily praised the movie's production values, Talmadge's stellar performance, and Harrison Ford's deft portrayal of Jeremiah and Kenneth.

Sidney Franklin also directed the first film adaptation of the Broadway play with sound. Fittingly, the 1932 film was produced by studio kingpin Irving Thalberg and starred his wife, Norma Shearer.

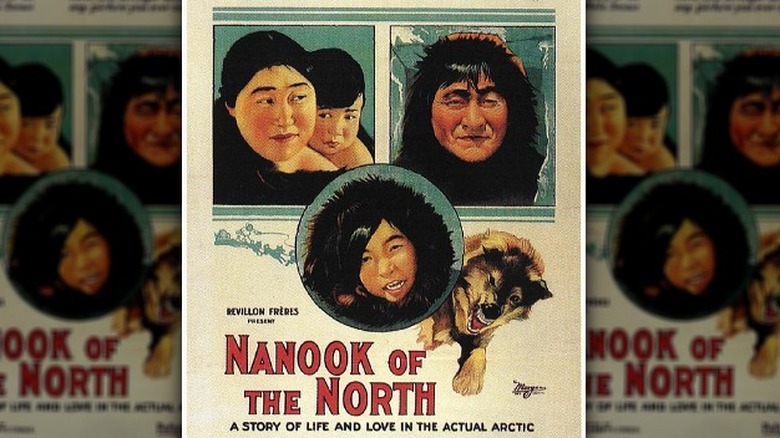

Nanook of the North

A chronicle of Inuit life on the northern Hudson Bay, Robert Flaherty's "Nanook of the North" earned distinction not only as one of the best reviewed and financially successful films of 1922, but also as cinema's first feature-length documentary. At the time, most nonfiction films, or "actualities," were simple, short travelogues, and as noted in Current, Flaherty's original intent was to make a dramatic film that happened to be set in the Arctic. Eventually, however, the film morphed into a hybrid of travelogue and stylized ethnographic study.

In its review, the New York Times lauded Flaherty's vision and the film's revolutionary realism, noting that when the audience views Nanook in a "real life-and-death struggle," the effect is "much more thrilling" than a battle between "two well-paid actors firing blank cartridges at each other!" Life reflected that while the daily life of Eskimos might at first seem dull, the film presents the "terrific struggle" of the hardy Inuits in "absorbingly dramatic fashion."

Although Flaherty spent 16 months shooting among the Inuits, according to Britannica, the authenticity of some aspects of the film later came under scrutiny. The featured locals were revealed to have been carefully selected by Flaherty for their photogenic looks and were paid for their appearances, and in one hunting scene, the seal prey was already dead, among other fakeries. Despite these revelations, Flaherty is still regarded as the father of the documentary, and "Nanook of the North" still retains its place in film history.

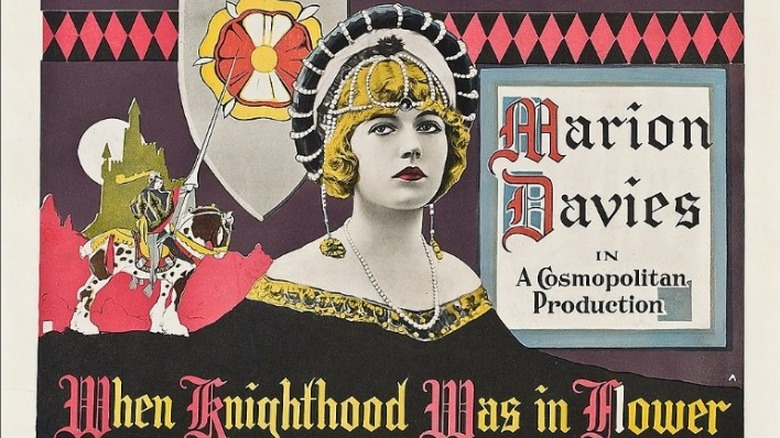

When Knighthood Was in Flower

Marion Davies, best known as newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst's mistress, was the star attraction of the 1922 critics' choice costume drama "When Knighthood Was in Flower." Robert G. Vignola directed the film, which was based on a novel by Charles Major, and Hearst's movie company, Cosmopolitan, footed the bill for the lavish production. In it, Davies plays King Henry VIII's sister, Mary Tudor, whose passionate romance with commoner knight Charles Brandon conflicts with her political marriage to elderly King Louis XII of France. (As noted by English Monarchs, the real Mary Tudor did not meet Brandon until after Louis' death, but did marry him against her brother's wishes.)

As reported in the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, the $1.5 million production took 140 days to shoot and used almost 300,000 feet of raw film. For one Paris street scene, 32 buildings were constructed and more than 3,000 extras were hired. The extravagant filmmaking paid off, as reviewers gushed and audiences flocked to the theaters. For the movie's 108-day New York run, 2,209 light bulbs lit the theater's marquee, and Davies' name was displayed with 10-foot high letters. Moving Picture World proclaimed the film exhibited "technical perfection" and matched the "gorgeousness, lavishness and magnificence" of recent foreign productions. Photoplay described the production as "superb cinema painting" and applauded the performance of Davies, who had yet to prove herself as an actress, as her most varied to date.

The Prisoner of Zenda

Silent film stalwart Rex Ingram directed Lewis Stone, Alice Terry, and Ramon Navarro in the 1922 screen version of Anthony Hope's wildly popular adventure novel "The Prisoner of Zenda." Stone plays a double role as the dissolute King Rudolf of Ruritania and as his sober lookalike cousin, Englishman Rassendyll, who takes Rudolf's place when he is drugged by his scheming brother, Black Michael, just before his coronation. The usurping Black Michael then kidnaps Rudolf and imprisons him at a castle in Zenda, and Rassendyll must undertake a daring rescue to restore his cousin to the throne.

As noted in the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, the production cost over $1.1 million and employed 23,000 people, including 26 costume designers and 10,000 extras. Ingram and leading lady Terry reportedly eloped during shooting and honeymooned together after production wrapped.

In its review, Variety called the story "the kind of romance that never stales – fresh, genuine, simple and wholesome" and declared that the film version "captures the imagination and holds it by a completeness of illusion." Variety also observed that the movie's unusual cinematography evoked a dream-like atmosphere that perfectly matched the mythic nature of the imaginary Ruritania. Though it bemoaned the film's overall inconsistency, The New York Times complimented Ingram's direction, describing his scenes as soft yet clear, with "unity and harmony," and praised his ability to stamp "his people with meaning, even when they are only flitting through the action."

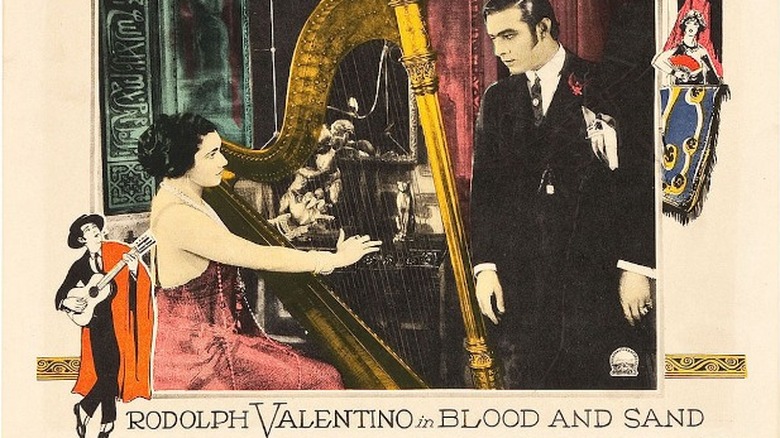

Blood and Sand

Hollywood megastar Rudolph Valentino cracked the 1922 "best of" list with "Blood and Sand," a contemporary romance set in the world of bullfighting. Directed by Fred Niblo and based on a novel by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and a play by Tom Cushing, the star vehicle also boasted contributions by two of Hollywood's most distinguished women filmmakers, editor and director Dorothy Arzner and screenwriter June Mathis. Valentino plays Juan Gallardo, the orphaned son of a poor shoemaker who marries childhood sweetheart Carmen and rises to fame as a daring matador. Juan's happiness and success are challenged, however, when temptress Doña Sol enters his life.

Fueled by Valentino's matinee idol status, the Paramount release broke attendance records in Los Angeles and New York, as detailed in the AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Life complimented the film on its atmospheric authenticity as well as Valentino's spot-on performance: "No one can dispute the fact that he is a remarkable actor – possessed of real grace, a great deal of pictorial attraction, and genuine ability." Niblo, according to Motion Picture News, "handled the production in a masterful way" – the "mass effects, the atmosphere, the acting" – and "the real bullfighting scenes have been matched with those showing the star" in a "thrilling" manner.

Shortly after "Blood and Sand" opened, Stan Laurel, of Laurel and Hardy fame, released a short parody of the film, "Mud and Sand," in which he played a matador named Rhubarb Vaseline.

Grandma's Boy

The only comedy to make the 1922 list, "Grandma's Boy" starred funnyman Harold Lloyd in his first full-length undertaking. Lloyd regular Fred Newmeyer directed the feature, and comedy master Hal Roach, another frequent Lloyd collaborator, served as producer and co-writer. As noted in PBS, Lloyd, who had started his career playing Chaplinesque tramp characters, introduced his spectacled everyman persona in 1917, and by 1921, the immense popularity of his short comedies had led to demands for longer projects like "Grandma's Boy." In its tailor-made story, Lloyd plays a timid 19-year-old who must overcome his fears to thwart both his bullying romantic rival and a tough jewelry thief, and win his sweetheart's love (played by Lloyd's real-life wife-to-be Mildred Davis).

According to the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, in its first weeks, the film smashed box office records in New York and enjoyed hugely successful runs in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Critics showered the film and Lloyd with praise. Moving Picture World deemed the feature Lloyd's "best picture ever," noting that it marked his entrance into a more complex type of story, one that raised "the standard of comedy from mere comedy in itself to a distinctive new level in the art of motion pictures." Variety called the movie a "knockout" and unlike anything Lloyd had previously done: "Lloyd not only shows his usual funny characteristics but does some surprisingly emotional acting." According to TCM, even box-office rival Charlie Chaplin was a big fan of the film.

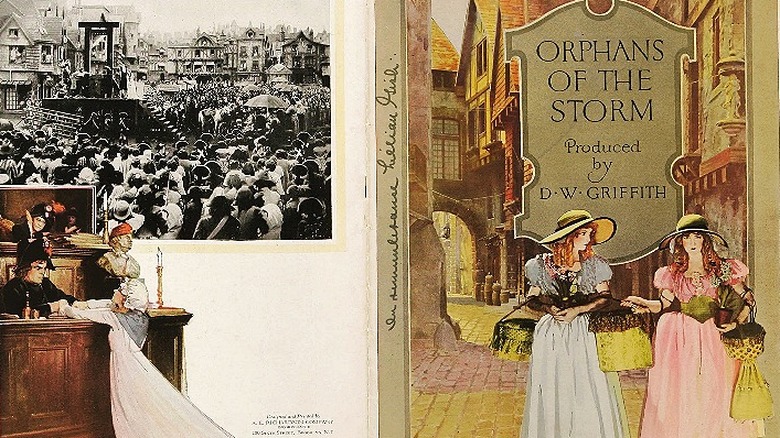

Orphans of the Storm

Clocking in at a butt-busting 249 minutes, D. W. Griffith's "Orphans of the Storm" earned the top spot on the Film Daily 10 best list of 1922. Based on a 19th century play made famous by stage actress Kate Claxton, the melodrama, set around the French revolution, co-starred real-life sisters Lillian and Dorothy Gish playing sisters Louise and Henriette. In the film's opening title cards, Griffith states that the epic is about "two little orphans who suffer first through the tyranny – selfishness – of Kingly bosses, nobles, and aristocrats" and then through the "new Government." Among the many hardships and horrors faced by the sisters are the plague, which causes Louise to go blind, abduction and imprisonment, starvation, separation, false arrest, and of course, riots and social upheaval.

After late December 1921 screenings of the film, then titled "Two Orphans," Griffith added some scenes and shortened others, and according to the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, cut the picture from 14 reels to 12 reels in response to audience criticism. Although viewers appeared less than enthusiastic about the picture, critics loved it. Rejoicing in what it described as Griffith's return to triumphant filmmaking, The New York Times called the movie a "stirring, gripping" blend of motion picture and melodrama, while Variety gushed that it was "as fine an example of the picture art as may be seen." Exhibitors Herald echoed those sentiments, declaring "Orphans of the Storm" a "living, moving, almost breathing triumph of pictorial perfection."