The True Story Of The Horror Movie That Caused A Riot

Although 1920's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is not the first horror film (that honor likely goes to Georges Méliès' 1896 short Le Manoir du Diable), it is in the estimation of many scholars the film that established the conventions and style of the genre. In a 2009 review, the late Chicago Sun Times film critic Roger Ebert declared The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari arguably "the first true horror film." Drawing a clear distinction between early cinematic efforts, such as the 1913 film serial Fantomas, Ebert wrote, "Caligari creates a mindscape, a subjective psychological fantasy. In this world, unspeakable horror becomes possible."

Much of that horrific mindscape is realized in the film's revolutionary design. Shot entirely on indoor sets, Caligari's surreal, Expressionist scenography is replete with painted shadows, jagged angles, and canted walls that externalize the madness of the plot and characters. A century after the film's release, the effect remains unsettling and claustrophobic.

Now recognized as a classic of the silent era, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was received favorably in its home country of Germany and around the world. Rich in symbolism and subtext as well as thrills, the film satisfied both intellectual and general audiences. However, in the United States, where anti-German sentiment continued to fester in the years after World War I, the film was met with suspicion and anger that, in one city, became a violent protest. This is the true story of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the horror movie that caused a riot.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and the birth of modern horror

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari opens on a young man named Francis talking with an old man. Soon, Francis begins to tell his shocking story, and the main plot of the film unfolds in flashback.

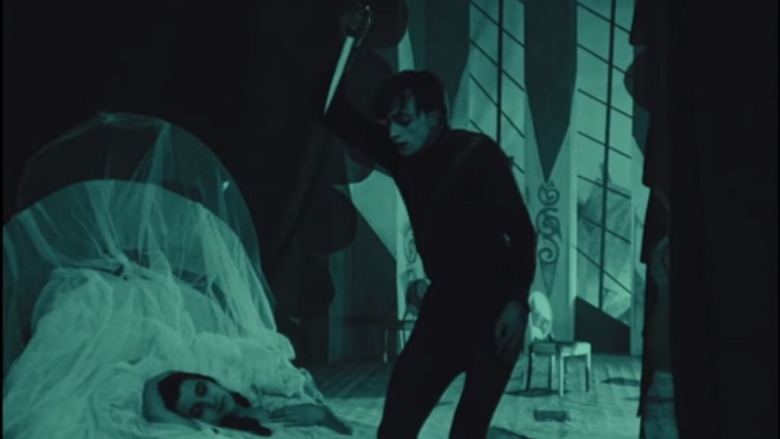

Francis and his friend Alan visit a fair in the city of Holstenwall. There, they watch an exhibition by a hypnotist named Dr. Caligari. Caligari's act features a hypnotized, black-clad sleepwalker named Cesare, whom the doctor keeps in a coffin-like cabinet. Cesare, Caligari explains, can be roused from his sleep to predict the future. When Alan asks the somnambulist when he shall die, Cesare ominously intones "The time is short. You die at dawn!" True to Cesare's prediction, Alan is found stabbed to death in bed the following morning. Ultimately, Caligari is revealed to be a madman who uses Cesare to murder for him.

Caligari establishes many conventions of plot and character that are cornerstones of the horror genre today, including its dreamlike structure, twist ending, and its reflection of the social issues of its time. As outlined by film critic Chris Vogner in his 2020 essay, "Lasting Fright: The Staying Power of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," these elements make for a horror film that is recognizable to modern audiences. "[Caligari] may be 100, but its otherworldly qualities make it feel more modern than much of today's fare," Vogner writes. "... Horror films have long provided a vessel for societal anxiety. ...Caligari's long, dark, painted shadow is still with us."

The antiauthoritarian roots of Caligari

By 1919, the writers of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, had their fill of war, tyranny, and an indifferent, complicit populace.

As detailed in From Caligari to Hitler, by Siegfried Kracauer, Mayer and his three younger brothers were turned out on the street by his successful businessman turned failed gambler father at the age of 16. Responsible for his siblings' well-being, Mayer sold barometers, sung in choirs, and took bit parts in plays to make ends meet. With a burgeoning interest in drama, he learned every aspect of theatrical production. However, by the outbreak of World War I, Mayer was working as a sketch artist in various Austrian cafes. The war took an enormous emotional toll on Mayer, and abuse at the hands of a military psychiatrist assigned to his case left him angry and embittered.

Born in Prague, Janowitz had been an army officer at the beginning of the war. Watching millions of young men sent to their deaths by an indifferent government left Janowitz with a volatile hatred of authority. A confirmed pacifist by the war's end, Janowitz settled in Berlin where he met Mayer. With shared hatred of authority and a love of the new medium of cinema, the two decided to write a film that would poetically express their angst. Drawing from Mayer's nightmarish experience with psychiatry and Janowitz's obsession with an unsolved murder that occured at a fair he attended as young man, the untried writers planted the seed from which Caligari would spring.

The unsettling Expressionism of Caligari

Celebrated for its painted shadows and off-kilter sets, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's hallucinatory visuals are the stuff of nightmares. The film's unsettling imagery is rooted in the art movement known as Expressionism. As defined by author R.S. Furness, author of Expressionism, the style was defined by "... a movement towards abstraction, towards autonomous colour and metaphor, away from plausibility and imitation." Expressionist art largely ignored formalism and the concept of canon. A famous example of Expressionist art is Edvard Munch's painting The Scream.

An assault on tradition with a focus on immediacy and extremes, the movement tended toward the mystical and the grotesque with often apocalyptic overtones. Expressionism also took root in the theater and literature, most notably in the works of playwrights such as Ernst Toller and George Kaiser, and author Franz Kafka.

Specifically, Caligari is a work of German Expressionism — an offshoot of Expressionism that is characterized by its specific relationship to German attitudes and society.

In his 2009 review titled "A World Slanted at Sharp Angles," film critic Roger Ebert expertly summarized the function of Expressionism in Caligari's set design. "The stylized sets, obviously two-dimensional, must have been a lot less expensive than realistic sets and locations, but I doubt that's why the director, Robert Wiene, wanted them," Ebert writes. "He is making a film of delusions and deceptive appearances, about madmen and murder, and his characters exist at right angles to reality. None of them can quite be believed, nor can they believe one another."

Robert Wiene was not the first choice for director

Erich Pommer, the chief executive of the German film production and distribution company Decla-Bioscop, accepted Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz's script. Despite the writers' total lack of experience in film, Pommer shrewdly recognized the commercial potential of Caligari. In post-war Germany, artistic achievement was the key to conquering the foreign film market, and The Cabinet of Dr, Caligari, with its unusual themes and structure, seemed like a surefire money-maker.

As detailed in From Caligari to Hitler, Pommer handpicked director Fritz Lang to helm the film. Lang, however, was already deep in production on a film titled The Spiders and was unable to pick up the project. Although he may have missed out on directing Caligari, Lang nevertheless became an iconic filmmaker when he directed the dystopian science fiction classic Metropolis in 1927.

The job of directing Caligari instead went to Robert Wiene. The son of prominent German stage actor Carl Wiene, Robert was a lawyer-turned-theater-manager before entering the movie industry. By the time Robert was assigned to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, he had directed 30 films. Along with his years of experience, Robert had one other qualification that made him a perfect fit for the film — his father had gone slightly insane at the end of his life, which, in the words of author Siegfried Kracauer, left Robert "not entirely unprepared to tackle the case of Dr. Caligari."

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's cast

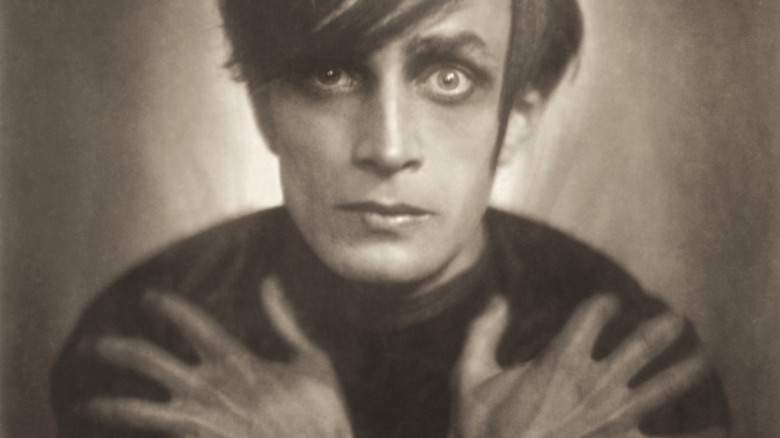

Although the character of Francis as portrayed by Friedrich Feher may be The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's main protagonist, his naturalistic performance takes a backseat to the film's Expressionist set design by Hermann Warm. The film's true stars are undoubtedly Werner Krauss and Conrad Veidt, who portray Caligari and Cesare, respectively. Providing pointed contrast to Feher and supporting actors Hans Heinrich von Twardowski (Alan) and Lil Dagover (Jane), Krauss and Veidt's highly stylized performances perfectly complement the film's macabre scenographics.

As documented by Nige Burton of Classic-Monsters.com, Krauss had embarked on a stage career before joining the German Imperial Navy. Upon his discharge in 1916, he began working in film. In the four years prior to being cast as Caligari, Krauss had gained a reputation for portraying sinister characters, making him an obvious choice for the film. Krauss, an unabashed anti-Semite and supporter of the Nazis enjoyed popularity throughout World War II as the star of propaganda films. According to David Stewart Hull, author of Film in the Third Reich, Krauss was blacklisted after the war. His attempt at a stage comeback in Switzerland was met with angry protests.

Veidt, who portrayed Cesare, Caligari's sleepwalking proxy, would enjoy a successful acting career in England and the United States. Labeled a traitor for his anti-Nazi views and for marrying a Jewish woman, Veidt was exiled from Germany. Taking up residence in Hollywood, Veidt continued to act, appearing in such classics as The Thief of Baghdad and Casablanca.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's controversial conclusion

Caligari's ending remains a topic of debate for film scholars a century after its release.

In a call back to the film's opening sequence, Francis is revealed as a patient in an insane asylum. Jane and Cesare are also inmates, and the man assumed to be Caligari is the asylum's director. Having heard Francis' mad ramblings about Caligari and Cesare, the asylum director declares he now knows how to cure the insane man.

For decades, many film scholars have assumed that the film's framing device and ending were imposed by the studio to soften its anti-authoritarian subtext. The origin of this theory lies in Siegfried Kracauer's 1947 book, From Caligari to Hitler. Kracauer, working from writer Hans Janowitz's memoirs, contends that the framing story and ending were added by director Robert Wiene. "... The original story exposed the madness inherent in authority," Kracauer writes. "Wiene's Caligari glorified authority and convicted its antagonist of madness. A revolutionary film was thus turned into a conformist one ..." Ultimately, Kracauer concludes that the film's ending was added to satisfy the need to deliver a commercially viable film.

However, critic Bert Cardullo, among others, disagree with Kracauer's assessment. According to Cardullo, the long-accepted interpretation of the film's ending as outlined by Kracauer is flawed. Removing the focus from Caligari as a symbol of unfettered authority and placing it on Francis's fractured psyche, Cardullo suggests Wiene corrected an oversight on the writers' part and more clearly realized their true intent.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was a hit in its home country

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was exactly what producers Erich Pommer and Rudolf Meinert and director Robert Wiene crafted the film to be – an inexpensively produced movie with artistic merit that would also appeal to a popular audience.

Backed by an extensive publicity campaign that featured posters with the ominous tagline, "Du musst Caligari werden" ("You must become Caligari"), the film was a worldwide success. However, in its native Germany, the boldly experimental horror movie struck a chord that was both resonant and ultimately prophetic. German film scholar Lotte Eisner, author of The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, writes, "at a time when Germany was still going through the indirect consequences of an abortive revolution and the national economy was as unstable as the national frame of mind, the atmosphere was ripe for experiment."

With its surreal visuals and grim tone, Caligari perfectly captured the malaise of post World War I Germany. The war had left Germany economically hobbled, politically rudderless, and embittered by the seemingly meaningless deaths of its young soldiers sent to kill and die at the behest of an uncaring government, says BFI. To many Germans, Caligari was the zeitgeist manifested in light and shadow.

Caligari conquers the world

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari ushered in a golden age of filmmaking in the Weimar Republic and established a distinctly German cinematic identity. Its release could not have come at a better time for the German film industry. With international film markets once again opening to German cinema following WWI, Caligari was free to conquer the world.

Met with acclaim in its home country, critics in Allied nations such as France and the U.S. largely agreed that the film was a masterpiece of avant garde filmmaking. As detailed by horror historian David J. Skal in his 1993 book, The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, prominent New York critic Kenneth MacGowan cited Caligari as an indictment of the staleness of formulaic American cinema, writing, "the most extraordinary production yet seen ... its narrative far more exciting and gripping than any but a very few of our native products." In Britain, writer Paul Rotha would call the film "... a drop of wine in an ocean of salt water." First in France and then throughout Europe, the word "Caligarism" came to define the "chaos of the post-war world."

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari sparked a riot in the U.S.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was not without its detractors, especially in the U.S. As documented by David J. Skal in The Monster Show, a showing of the film at Los Angeles' Miller's Theater on May 15, 1921, sparked a daylong protest that devolved into a full blown riot. However, it was not the film's content with which the protesters took issue. With anti-German sentiment running high three years after the end of World War I, the picketers, composed of veterans from the Hollywood outpost of the American Legion, were angry that a film from America's wartime enemy was being shown in the movie capital. Viewing German culture as a threat to democracy, the protesters were dedicated to ensuring that hard-earned American dollars stayed out of enemy coffers.

Brandishing signs which read, "WHY PAY WAR TAX TO SEE GERMAN-PICTURES?" a group of hundreds of veterans descended on Miller's Theater at noon, says Forgotten History. By day's end, the crowd swelled into the thousands, as regular citizens and active duty naval officers joined the protest. Street traffic ground to a halt, and 35 police officers and navy provost guards were called in to defend the venue. Although American Legion officials called for calm, waves of protesters rushed the police. Unable to break the defensive line through sheer force, the rioters pelted the building and its defenders with eggs. Fortunately, American Legion leaders were able to disperse the protest when the theater agreed to replace Caligari with the American film, The Money Changers.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a labyrinth of complex themes

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is far more than the sum of its plot, characters, and set design. While attempting to expose the wartime exploitation of common people in the guise of Conrad Veidt's Cesare the sleepwalker by the cruel, unchecked whims of authoritarian government as represented by Werner Krauss' Caligari, screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz opened The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari up to a variety of interpretations that continue to intrigue cinema scholars and critics.

Among the themes present in the film are explorations of the dualities of sanity and madness and reality and illusion. However, the most intriguing interpretation of Caligari is Sigfried Kracauer's contention that the film is a prophetic piece of art that predicts the rise of Adolf Hitler and outlines the conditions that led to Germany's embrace of Nazism. In his introduction to Robert V. Adkinson's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: A Film, Kracauer writes, "Whether intentionally or not, Caligari exposes the soul wavering between tyranny and chaos, and facing a desperate situation: any escape from tyranny seems to throw it into a state of utter confusion. ... Like the Nazi world, that of Caligari overflows with sinister portents, acts of terror and outbursts of panic."

Caligari greatly influenced American cinema

Although few German Expressionist films could match Caligari, its style and themes of madness and the fantastic led directly to the production of such classics as Nosferatu, Waxworks, and M, which in turn influenced American horror and crime films of the 1930s and 40s.

As detailed by the Australian Center for the Moving Image, the Expressionism of Caligari would most notably seep its way into Universal Studios' classic monster movies, informing the visuals and themes of such horror films as Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy (directed by German expatriate Karl Freund), and The Black Cat (directed by German film industry veteran Edgar G. Ulmer).

With Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933, many German filmmakers fled to the U.S. An influx of German talent, including such luminaries as Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau, further entrenched Expressionism in American cinema. During the late 1940s and 50s, Expressionism's chiaroscuro lighting and dark themes found their way into low budget crime films marking the classic period of film noir.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's enduring legacy

Over a century since its release, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari continues to inspire artists across a multitude of media. Musicians ranging from the Cure's Robert Smith to David Bowie to Rob Zombie have drawn inspiration from Robert Wiene's film for fashion, stage design, and music videos.

Caligari's influence can still be felt in the dark surrealism of such directors as David Lynch and Guillermo del Toro. However, as detailed by ACMI's Matt Millikan, the modern filmmaker most inspired by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is undoubtedly Tim Burton, the imagination behind such quirky hits as The Nightmare Before Christmas and Ed Wood. Throughout his career, Burton has used overtly Expressionist elements and visual callbacks to Caligari as part of his unique cinematic vision. Among Burton's most obvious homages to Caligari are the physics-defying, two dimensional sets of Beetlejuice and the eponymous Edward Scissorhands, whose appearance is clearly based on Caligari's Cesare.