The Tragic Truth About The The Permian Mass Extinction

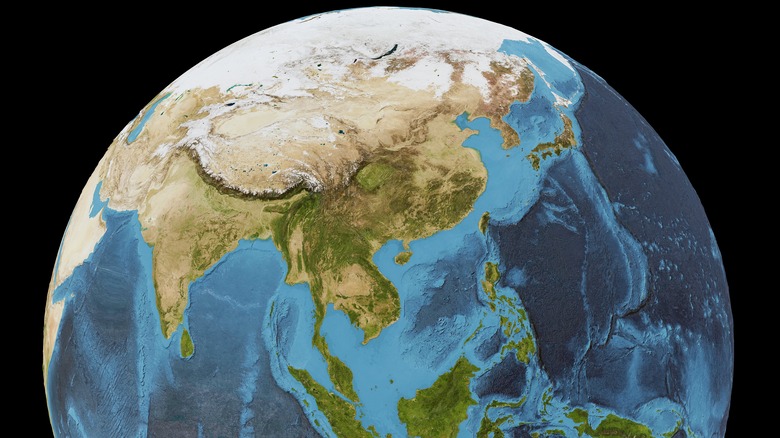

If you've never heard of the Great Dying, it's exactly what it sounds like— lots of death, followed by very impressive mold, and probably even better mushrooms. The Permian Mass Extinction was the largest extinction in Earth's history, which is maybe lesser known since it's kind of old news— 252 million years old to be (somewhat) precise, according to Britannica. While this mass murder was taking nearly 95% of life in the ocean and 70% of life on land, Pangea was still rocking out, dinosaurs weren't even a thing because reptiles were still figuring themselves out, and creatures both plants and critters alike were incredibly plentiful and diverse, per National Geographic.

This reckoning marked the end of the Paleozoic, an era that started 541 million years ago. This wasn't the first extinction the planet had endured, but it was certainly the most significant, being that it was large enough to possibly make all complex organisms start all over again. Here's what happened during the Permian Mass Extinction, and why, while it was pretty freaking cataclysmic, life still bounced back like a champ.

It may have been an asteroid that started it

Just like the impactor that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, many geologists believe a huge rock flying into the Earth may have been the culprit for the Permian extinction. Scientists have found rubble and craters from the Late Permian in Australia, according to Earth Archives. The rubble in question holds a very rare hunk of shocked quartz which only forms during asteroid events, according to National Geographic.

These fragments have also been found in Antarctica, which was the same general area as Australia during the Permian, since Pangea wouldn't split up for another 100 million years, per ArcGIS. However, it's also believed that if an asteroid did in fact give Earth another dimple, it most likely barreled into the ocean and kicked up the shocked quartz after the landing. This has left us with nothing else to work with since the ocean floor gets a tectonic makeover every 200 million years, per Earth Archive. Thanks a lot, ocean!

Or maybe it was the ocean

Again, thanks a lot, ocean! Scientists also think the big blue sea could have had a hand in this mass murder as a result of the changing currents when the continents started to part ways, according to National Geographic. This would have left deep pockets of stagnant water while the weather patterns were in flux. When water is still, the poop product of marine bacteria, a.k.a. bicarbonate, can start to grow its own colonies. Once they've flourished to a certain point, they release carbon dioxide — a nasty but powerful greenhouse gas. Per Nat Geo, 95% of oceanic life would have struggled to breathe and eventually fallen asleep ... forever.

So how would that have mattered to life on land? Not my ecosystem, not my prob— those smug Synapsids and Sauropsids probably snickered. Well, it turns out, the ocean is pretty big! So with enough carbon dioxide floating up into the atmosphere, these Komodo Dragon-rodent-looking crossovers would have had to endure the adverse effects of global warming as well, per Britannica.

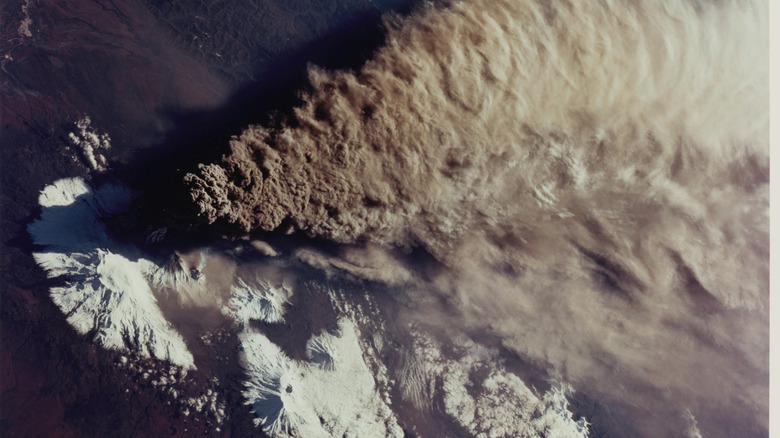

It was probably a volcano

On the subject of greenhouse gasses, scientists have also found a very likely accomplice for the mass extinction laying around in Siberia: A massive field of volcanic rock. In the late Permian, multiple volcanoes started popping off in this area in one of the largest volcanic events in Earth's history, according to Earth Archives. But rather than swallowing the Earth in lava— although that's a pretty epic image— the volcanoes released oodles of ash and greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, creating a tremendous environment for all things to get toasty, per National Geographic.

According to Stanford, the eruptions could have raised the temperatures of the oceans by 20 degrees, which caused the oxygen levels to plummet by 80%. On top of that, the gregarious amounts of ash from the volcanoes could have blocked out the sun for a prolonged period of time, robbing plants of their ability to photosynthesize, leading to catastrophe for the entire food web, per Earth Archives. In hindsight, a big lava hug probably would have been preferable to the species trying to survive all that garbage the volcanoes coughed up.

It caused a ton of acid rain

Most likely, it wasn't just one event to blame for the Permian mass extinction, and it was more of a cocktail of the catastrophes discussed, according to National Geographic. But one thing is for certain— whatever happened during the last run of the Paleozoic, it caused the most terrifying rain showers for life on Earth. Scientists have confirmed that large amounts of acid rain poured over Pangea during Permian by finding the compound vanillin (a byproduct from these menacing drizzles) in the Dolomite Mountains in Italy, per Imperial College London.

Now, the clearest culprit for the acid rain would be the volcanic eruptions in Siberia. This is because the gas that plumes into the atmosphere during these events is thick enough to block out sunlight for long enough to make temperatures drop, making the perfect conditions for acid rain and snow to cascade upon the Earth, according to National Geographic. But before the visual of disintegrating animals and fish started to bubble up, this event was more about what it did to the plants. The acid falling from the sky would have fried the soil, making it just about as acidic as a lemon, per Imperial College London. This would have made it impossible for flora to thrive, followed by herbivores, followed by carnivores. The lesson here? The sun and plants run this town.

Things got really hot, and then they got really cold

According to National Geographic, Paul Renne, a geologist from the Berkeley Geochronology Center, noted, "In 1783, a volcano called Laki erupted in Iceland. Within a year global temperature dropped almost two degrees." Now consider that the eruptions in Siberia are estimated to have lasted for hundreds of thousands of years. The consensus from this historic eruption is that the sun was blocked out for so long by sulfate molecules, it sent Earth into an 80,000 year Ice Age, according to United States Press International.

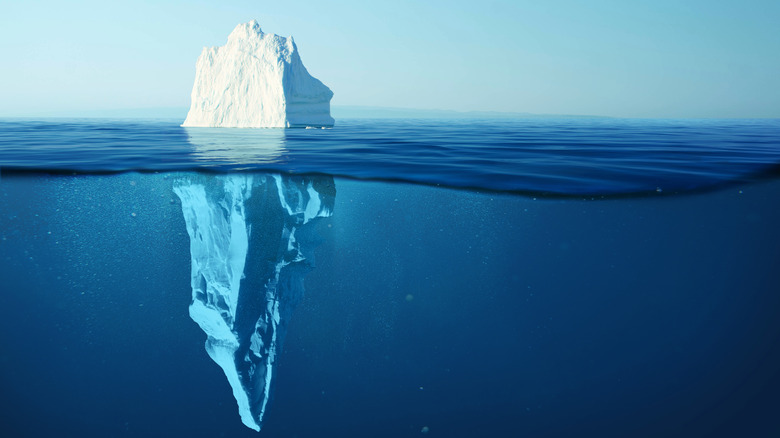

Evidence of the Ice Age has been found in samples taken from China's Nanpanjiang River basin that showed ash beds from the late Permian, as well as a huge decrease in marine life which can only be explained by lower ocean levels, per United States Press International. The thinking is that as glaciers formed in the oceans, the sea level lowered, making life impossible for creatures who lived in the shallows. So, maybe most of life actually died due to the shivers, rather than from global warming.

It obliterated life in the ocean

If not already apparent, the residents under the sea took the biggest brunt of the deal during the Permian mass extinction. More than 95% of marine life kicked it on account of embarrassingly low levels of oxygen— a result of super warm water, according to Britannica. Conditions were evidently most severe down in the tropics, but those fishies actually did a lot better than their neighbors who lived closer to the poles. This was probably due to tropical species having the ability to pick up and swim towards temperatures that were closer to their original heat preferences, whereas marine life that lived in colder areas of the world was already maxed out when things started to warm up, according to Stanford.

What life was left in the ocean is actually uncharacteristic of most extinction patterns, since the folks at the bottom of the food chain tend to survive. But because there was little to no oxygen left at the bottom of the ocean where marine food chains begin, it seems that fish-lizards and mollusk-like squids were the ones able to keep on keepin' on, according to Science News by Agu. Fossils of the nekton creatures have been found in Triassic rocks layers that followed immediately after the Permian, but what they were eating is still a mystery. Each other, maybe?

Over half of the earth's animals and plants died

Scientists estimate that around 70% of life on land bit the dust during the Great Dying due to a lack of flora to feast upon, according to Britannica. How do scientists even know this without a bunch of massacred fossils to show for it? Well, that's actually kind of the point! Similar to how geologists have mulled over the rock layers from the Permian followed by the Triassic that tell us about the dead oceans at that time, fossils have shown that forests and terrestrial creatures were livin' the good life before this savage event took place, then it all kind of goes blank, according to National Geographic.

Loads of animal fossils are understandably hard to come by from 250 million years ago, but there are a few to be found in a remote slice of wilderness in South Africa. The majority are from a long-gone group called synapsids, which are a fun-looking hybrid of reptiles and mammals, according to National Geographic. These bad boys and girls were the first thriving vertebrates to walk on land in Earth's history.

In geologic time, it happened in a snap

Now, there's still some squabble over exactly how long it took to kill just about everything on Earth, but most scientists do agree that it didn't take millions of years to get the ball rolling towards a total apocalypse. The reason why scientists know the Permian extinction happened quickly is that the fossil record doesn't show a gradual decline of life— but rather, a clear-cut boundary of when most living things vanished, according to National Geographic.

Now, that isn't to say that the conditions leading up to the extinction didn't take some time, give or take 15 million years, according to Britannica. But as far as when most marine animals, terrestrial species, and plants dropped dead, different scientists have estimated that it may have taken between a few centuries to 200,000 years, according to PHYS. Talk about a gap! But hey, try solving a murder mystery from 10 years ago let alone 250 million. This is based on the fact that they have yet to come across any evidence that there was an early onset event that made flora and fauna die out gradually. For the study of Earth's extinctions at large, scientists think new developments in our understanding of the Permian period may reflect that other mass dying events happened in the blink of an eye, per PHYS.

It left a massive rotting ecosystem

Not everything had such a hard time when the majority of life was lost on the blue planet— fungus was actually pretty stoked about it! In the rock layers before the Permian extinction, tons of microscopic fossils left a legacy of a thriving and diverse ecosystem, per National Geographic. Moving up in the sediment layers, all signs of pollen and plant particles pretty much vanish and are replaced with oodles microbes. This decaying, rot-filled environment became only suitable for scavengers, which is why smaller animals tended to make it out better than larger ones during the end of the Permian, per National Geographic.

All this rot and mold may have had the Siberian eruptions to partially thank for their infiltration. According to Britannica, nickel helps certain methane-producing microbes thrive, and is plentiful during volcanic events. So, some scientists think that the eruptions not only released a heaping amount of greenhouse gasses but also helped fuel microorganisms that pump out noxious methane too. Poison and farts for everyone!

We have a pretty crazy animal to thank for our existence

Before most of life kicked it on Earth, terrestrial animals were going through a pretty fun period of evolution. Most of the land animals during the Permian had a mix of mammalian and reptilian traits, according to Earth Archives. One of the most important critters that did make it out of Earth's biggest apocalypse looked like a hodgepodge of a lizard and a hog— the humble hero, Lystrosaurus. This 3-foot-long animal most likely made it out alive due to its big lungs and burrowing capabilities that allowed it to breathe under super difficult conditions while also finding food underground, per National Geographic.

Remnants found of this reptile pig also show its ability to take long strolls to the far reaches of Pangea, according to National Geographic. By migrating to ecosystems that would support its survival, the Lystrosaurus is undoubtedly a species we have to thank for its tremendous contribution of repopulating the planet into the Triassic— particularly mammals. The Lystrosaurus also contributed to a huge aspect of geological research, as its fossils found in Africa, China, and Antarctica, laid evidence for the theory about plate tectonics scientists were still scratching their heads over until the 1960s, per National Geographic.

This was the time for reptiles to shine

In a time when carbon dioxide ruled the molecules of the atmosphere, certain reptilian-like species were able to strut into the Triassic thanks to a few helpful advantages, according to Earth Archives. Like the lizards we find today, fossils like the Kongonaphon, a mighty ancestor of the dinosaurs that stood a whopping 4 inches high, breathed with one lung while the other brought in oxygen, according to National Geographic. This was a great advantage to have during a time when the big O was in devastatingly short supply, and it's probably why Sauropsids did so much better than their more-mammalian counterparts. This was also a case where size definitely mattered, since being itty bitty meant these little ancient lizards could satiate themselves much easier— and that really, really helps when the pickings were indubitably slim.

There still was quite a bit of evolutionary work to be done for Sauropsids to become the glamorous dinosaurs we all admire today, which could have taken up to 15 million years after the Permian mass extinction to even become cold-blooded reptiles, according to National Geographic. When these animals first came out on top of judgment day, they were still warm-blooded-salad-eating vagabonds and were completely ignorant that they would eventually make the most menacing creatures the planet has ever seen, per National Geographic.

Today's warming climate mimics what occurred in the Permian

From the fossil records scientists have uncovered from this historic mass murder, they can tell that Earth's temperatures started out very similar to today, according to PHYS. The Permian mass extinction was initiated by greenhouse gasses, and unless folks are living under a rock like a Lystrosaurus, it's easy to draw an immediate parallel to the situation we've found ourselves in now. In this case though, society is the volcano spewing loads of poisonous fumes into our delicate atmosphere on the daily.

According to Stanford, projections for Earth's future temperatures show that we'll have heated the oceans to 20% of what they were in the late Permian by 2100, and up to 50% by 2300. Estimates like these hint at a similar situation we may be dealing with in the very near future. The question is, who's going to make it through? Will humans get smaller, develop scales and short arms adorned with claws? At this point, we might only be able to hope so.