The Mythology Of The Finnish Hero Väinämöinen Explained

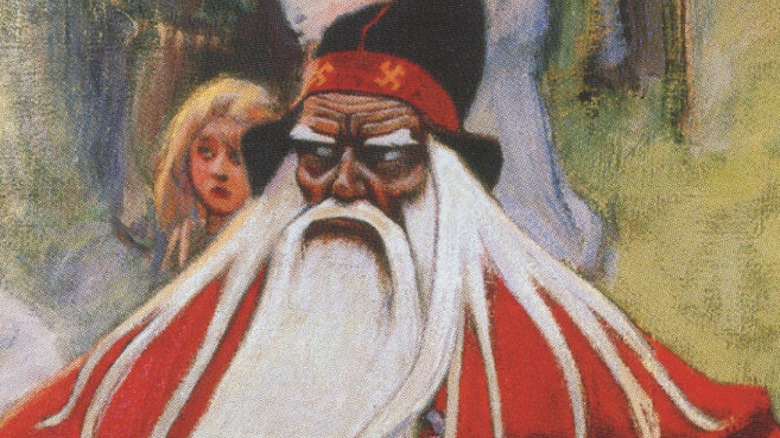

Hero, shaman, irascible demigod, wizard of song-battles, fashioner of pike-bone harps, sleigh-rider and more: this is Väinämöinen (pronounced "Vai-nya-moi-nen," stress on the "Vai"). Along with the "eternal blacksmith" Ilmarinen and the good-hearted (but womanizing) rapscallion Lemminkäinen, these three characters drive the central narrative of "Kalevala," the epic poem of Finland.

Everything we know about Finnish myth and its central hero, Väinämöinen, comes from "Kalevala," an epic poem first published in 1835, then revised and re-published in 1849. As Kalevalaseura recounts, author and physician Elias Lönnrot (1802-1884) traveled the Finnish countryside collecting oral tales, particularly in the region of Karelia in Finland's southeast. He gathered them, re-wrote them in poetic meter into a single, interwoven narrative in "Kalevala," and helped deliver Finland's national identity to itself. This was critical for a country ground under the competing thumbs of Russia and Sweden for at least 700 years, and which didn't become independent until 1917 (per InfoFinland).

Lönnrot did for Finnish myth what Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson did for Norse tales of Odin, Thor, Loki, and more: He preserved them in print. Sturluson (1178-1241 CE), as the Icelandic Literature Center says, did so 800 years ago, centuries after Iceland had become Christianized. Around that same time (1150-1350 CE), Sweden went on Christianizing crusades into Finland. After that, Finns still held onto their traditions and stories, Ere Now explains. And now? We've got an entirely unique mythos waiting to be told.

Gandalf meets Tom Bombadil

Väinämöinen has some things in common with other wandering, wizened wizards. Merlin from Arthurian legend comes to mind. So does Odin in one of his most widely used disguises — the old, cryptic sage in a hood and carrying a staff. Both characters are magical, have vision beyond mortals, and guide events behind the scenes. It's not too hard to imagine that knowledgeable elders would have been venerated this way in various cultures.

And who else do you think of when we say "wandering wizard with a hood and staff"? How about Gandalf from J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings"? Tolkein synthesized and remixed Western folklore in a manner analogous to how Snorri Sturluson and Elias Lönnrot compiled Norse and Finnish myth, respectively. It's no secret that Väinämöinen was part of the inspiration for Gandalf, as sites like Ancient Origins and Music and My Mind recount. Tolkien split some of Väinämöinen's aspects — singing, writing poetry — and off-loaded them onto Tom Bombadil, that merry, immortal, frolicking creature that Frodo, Sam, Pippin, and Merry encounter on their way out of the Shire. (Bombadil didn't make the cut for the 2002 movie.)

That's enough to forge a perfect vision of Väinämöinen: a bit mischievous, a bit arrogant, a bit gregarious, a bit wise, and steeped in magic. Wandering the woods, communing with nature all the while.

Guiding spirit of the Finns

As Kalevalaseura explains, Väinämöinen's appears in most of the stories in "Kalevala" (available in full online on Project Gutenberg in its older, original 1888 translation). Out of the 50 smallish, more-or-less contiguous tales in "Kalevala," Väinämöinen appears in over 30 of them: runos (tales) 1–10, 16–21, 25, and 35–50.

Whether Väinämöinen appears as the main character or a companion, retrieving the magical Sampo or soothing animals with his harp, he's always there. He's like the guiding spirit of the Finns and the natural world. Väinämöinen even more or less "finishes" the whole "Kalevala" by baptizing a boy born of the virgin Marjatta to be the leader of the Finnish people. And yes, that part of "Kalevala" is so uncannily similar to Christian belief that folks might wonder if there wasn't some cultural cross-pollination at play.

Väinämöinen is often described as "weary" and "steady old Väinämöinen," as well as "the everlasting singer" and "the eternal sage." When he finishes his role in "Kalevala" — and therefore his role in forging the modern Finnish nation — he just sort of sits on his boat and feels tired. But he leaves behind on land his handmade harp, the Finnish kantele, as a gift to the people. (If you want get a sense of the spellbinding beauty of kantele music, listen to the lullaby "Nuku Nuku" on YouTube.)

A shaman shapeshifting over time

As Kalevalaseura says, Väinämöinen's name first appears in print in 1551, mentioned by Bishop Mikael Agricola. Agricola, as My Helsinki explains, helped standardize and spread a written version of the Baltic-Finnish language that included Latin, Swedish, and German elements. As Get Blend says, this didn't start to happen at least until 1450 CE, which is really late for the written word game. The first Finnish novel wasn't published until 1870. "Finnish," as opposed to the country's other regional languages, such as that spoken by the indigenous Sami, wasn't even adopted as the official national language until 1892. That's over 50 years after the revised "Kalevala" was published.

This is all to say: No one has any clue where stories about Väinämöinen came from, or for how long they existed. Väinämöinen, the figure, arose sometime between when Finland was first permanently settled about 8800 BCE, as InfoFinland cites, and when Agricola wrote down the name in 1551.

In identical fashion, Väinämöinen himself has no origins in "Kalevala." He's just there, like a creator god, at the start of the world, helping a great goose lay the eggs that will crack to become the land of Earth. He's also a shaman and intermediary to the spirits who can travel to the world of the dead, Tuonela, and back. It stands to reason that Väinämöinen accumulated multiple storytelling roles as time went on.