The Most Important Battles Of The Civil War

According to Britannica, the American Civil War began when 11 Southern U.S. states seceded from the Union, fearing newly elected president Abraham Lincoln would end slavery. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy: although Lincoln only initially resolved to preserve the union, the war the Confederacy started eventually evolved into a struggle against slavery itself. When the guns fell silent 4 years and some 750,000 deaths later, the institution of owning other human beings was outlawed, and the nation remained intact.

But it was a long, terrible road, marked by high drama, immense human suffering, epic political intrigue, superb and terrible generalship, and absolutely appalling bloodshed. Some of the battles that defined the war still rank among the most famous of the 19th century — and among the bloodiest engagements in American history. So what were the most important ones? From Bull Run to Chancellorsville, and Vicksburg to Petersburg, here's a (decidedly non-exhaustive) list.

First Manassas (July 21, 1861)

Neither side expected the war to last long. Infamously, civilians followed the Union Army to Manassas to see the entertaining show the war's first major battle would surely turn out to be, according to the National Park Service. They were in for a rude awakening.

Union General Irving McDowell led his 35,000 man army to seize the Manassas railroad junction in Northern Virginia, which would open the road to Richmond. He faced 20,000 men under General P.G.T. Beauregard, while History says 11,000 rebel reinforcements under Joseph Johnston were swiftly rushed to the battle just in time.

Federal troops slowly pushed a Confederate force half their size across Warrington Turnpike and up Henry House Hill, but Confederate reinforcements brought the engagement to a stalemate. General Barnard Bee (who was killed later that day) remarked that Thomas J. Jackson's brigade was "standing there like a stone wall!" It's unclear if this was a compliment or an insult, but it was the birth of "Stonewall" Jackson's lionizing nickname. By late afternoon, the two sides were of roughly equal strength. General Beauregard then ordered a counterattack along the whole line that routed the Federals and sent them fleeing towards Washington. The Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas) was over, and both sides began to realize that a long and terrible war lay ahead.

Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862)

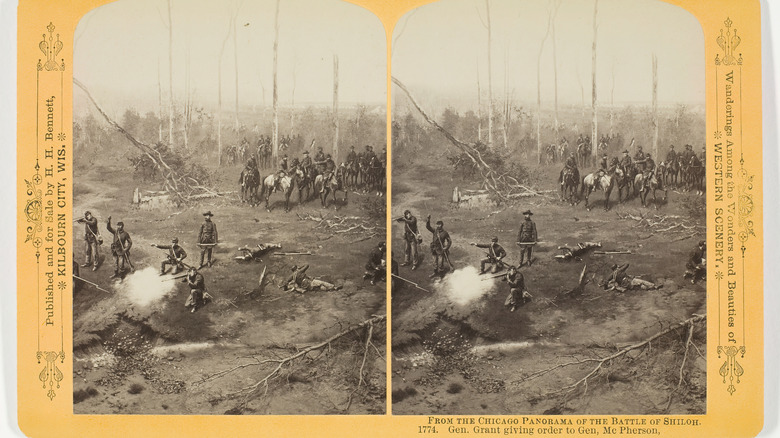

History says Ulysses S. Grant's armies had enjoyed a fairly easy ride in the beginning of the war, marching down the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and knocking out Confederate forts Henry and Donelson with relative ease. But Confederates under General Albert Sidney Johnston were merely waiting for the right opportunity to hit back. Johnson didn't have all day — he needed to strike before Grant's 42,000 men could link up with 20,000 reinforcements under Don Carlos Buell and move on Corinth, Mississippi.

On April 3, the Rebels advanced near Shiloh Church, according to the National Park Service, and they attacked on April 6. The Federals were completely taken by surprise, but they managed to rally and fall back to Pittsburg Landing in one organized piece, thanks to the ferocious defense put up by some cut-off Union forces in what became known as "the Hornet's Nest." Fighting faded with daylight. The Union had been pushed back two miles. History Net details a famous exchange between Generals William Sherman and Grant. Sherman said, "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" Grant calmly responded, "Yes. Lick 'em to-morrow, though."

And they did. Union reinforcements arrived during the night, and the whole federal army attacked the next day, driving the rebels back. National Geographic says that the death of General Albert Sidney Johnston during the battle was a devastating setback for the South, which Jefferson Davis later claimed was "the turning point of our fate."

Seven Days' Battles (June 25 - July 1, 1862)

Britannica says that in 1862, George B. McClellan took his Union Army of the Potomac on a long flanking mission to approach Richmond from the east, rather than simply advancing towards the Confederate capital from the north. Everything about the resulting Peninsular Campaign — including the world-changing but tactically indecisive clash of the Ironclads at Hampton Roads (via Britannica), which instantly made wooden warships obsolete — was loud, slow, and lumbering. By the time McClellan's men finally reached the outskirts of Richmond, the rebels had rallied, and the Seven Days' Battles began.

According to History Net, when the Confederate commanding General Joseph E. Johnston was wounded, Robert E. Lee — then a military advisor to President Jefferson Davis — was called in to replace him. McClellan's next attack, at Oak Grove on June 25, proved indecisive. Lee counterattacked the next day, but poor performances from Stonewall Jackson and A.P. Hill resulted in a Federal victory. Still, inexplicably, McClellan withdrew. More fighting followed as the Union army fell back. Even after a sharp victory at Malvern Hill, McClellan — spooked into believing he faced a much larger army than he actually did — retreated back to the Peninsula. Richmond was safe, for now.

McClellan's timid — perhaps pathetic — performance against an inferior enemy would haunt his reputation forever. Meanwhile, Lee, now in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, was just starting to make a name for himself.

Antietam (September 17, 1862)

Defensive victories inspired Robert E. Lee to take his army of Northern Virginia on its first invasion of the North in late summer 1862. Britannica says he believed a victory on Northern soil would harm Lincoln's party in upcoming midterm elections, increase the chances of European aid to the South, and perhaps pull Maryland into the Confederacy (which would devastate the Union, given the location of Washington, D.C.). It wasn't to be. In a nation-saving stroke of good fortune, a Union soldier happened upon Lee's plans. Even the timid George B. McClellan was emboldened. He remarked, "Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home."

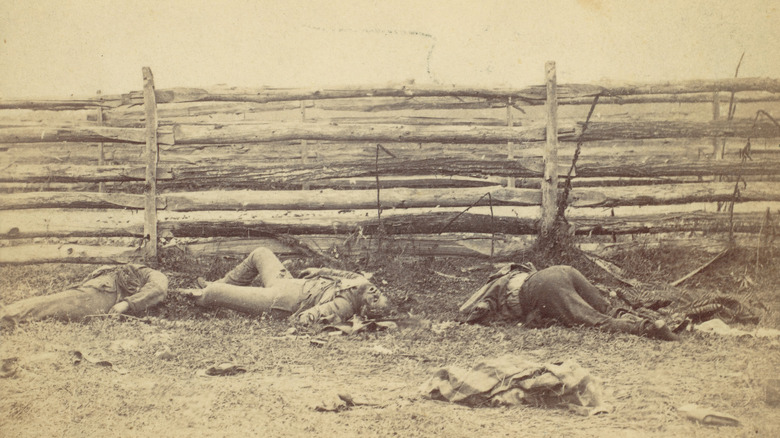

The battle began near the town of Sharpsburg, by Antietam Creek, on September 17. NPR states that fighting was savage in the Cornfield, where Union troops assaulted the Confederate lines. "Bloody Lane" fell to Federal troops after much carnage. And Burnside Bridge was where Union troops nearly cut off Lee's escape before Confederate reinforcements halted both them and the fighting. By the end of the bloodiest day in American history, 23,000 men lay dead or wounded around Sharpsburg.

But the tactical stalemate was a Union strategic victory: Lincoln finally had the win he needed to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, changing the North's war aims from simply preserving the Union to freeing enslaved people. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania notes that this shut the door on European intervention for the Confederacy.

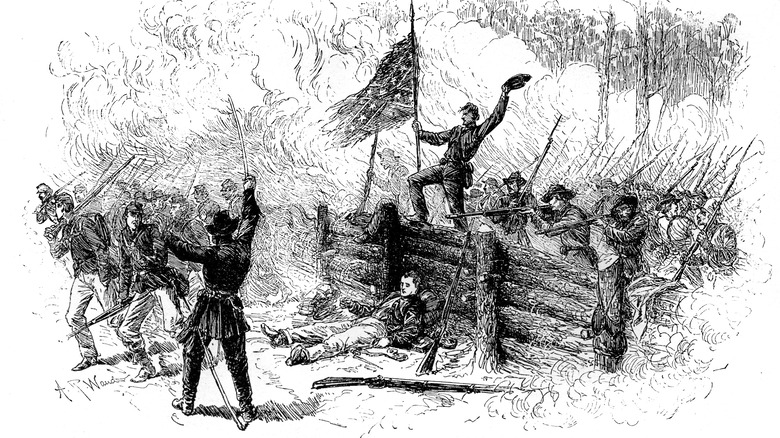

Chancellorsville (April 30 - May 6, 1863)

In late 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac was under significant pressure from Lincoln to capture Richmond. To get there, they had to cross the Rappahannock River. The American Battlefield Trust says the resulting Battle of Fredericksburg was a humiliating defeat for the Union. But a few months later, they'd try again. History says General Hooker, now commanding the Union Army, drafted a bold plan: His cavalry would raid Confederate supply lines. Then, a third of his massive, 115,000 man army would cross the river again near Fredericksburg, holding the Confederates in place, while the other two-thirds would swing around Lee's left flank, forcing an engagement that Lee's comparatively tiny, 60,000 man force couldn't hope to win.

Lee won anyway by ignoring the conventional wisdom of war. One of his chief subordinates, Thomas Jackson, was nicknamed "Stonewall" due to his defense at Bull Run. Oddly, it was Stonewall's offensive talents that made him so dangerous. Lee risked everything by splitting his tiny force and having Jackson smash into the exposed flank of Hooker's army. It worked brilliantly: the Federals were routed and fled. It was Lee's masterpiece.

But it was also his last major victory, and it cost him dearly. While returning from a nighttime patrol, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men. He died days later. How he would've performed at Gettysburg a month later is one of the most common "what if" scenarios of the Civil War, according to Emerging Civil War.

Vicksburg (May 18 - July 4, 1863)

According to the American Battlefield Trust, whoever held Vicksburg held the Mississippi River: a vital logistical artery for the South that connected its eastern and western halves. Said Lincoln, "Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket."

Luckily, the commander of Union forces in the trans-Mississippi theater, Ulysses S. Grant, was up to the task. Britannica details his brilliant campaign to take the small but well-defended city. High, river-facing bluffs and swamps to the north made it hard to seize from any direction but the south and east, where Union troops were nowhere near. But the article says Grant got around these disadvantages with diversionary raids and secret river crossings to the south. He even launched an unexpected strike not directly towards Vicksburg, but to Jackson, Mississippi, severing Vicksburg's supply lines. Only then did his forces smash those of John C. Pemberton and arrive at the outskirts of the city.

The article continues, detailing a failed attempt to seize the city, stiff Confederate resistance, and the siege that followed. After 47 days, starving, dwindling rebel forces compelled Pemberton to surrender the city. It was the 4th of July, 1863. The South had suffered a catastrophic loss, not just of the city but of the entire Mississippi River. And it was only a day after Robert E. Lee's defeat at Gettysburg. Although the war raged for two more years, the Confederacy would never recover.

Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863)

Robert E. Lee had invaded the North once already in 1862, in the hopes of scaring the Union into ending the war. He was beaten back at Antietam, but more defensive victories in Virginia inspired him to try again in late spring 1863, per History Net. This time, he attacked Pennsylvania. Elements of his 75,000 man army clashed with the 90,000 men of the Army of the Potomac on July 1, just days after George Meade had assumed command (via Britannica).

The first day saw an escalating conflict in which both armies arrived piecemeal and wrapped around the small town of Gettysburg. Then, Confederate forces outflanked and routed the Union, forcing them to retreat to the hills south of town. The next morning, Confederate leaders realized the Union was well dug in on the high ground, and they spent July 2 trying unsuccessfully to break their flanks at Culps Hill and Little Round Top (via Britannica), which ended with a legendary Union bayonet charge. On the third day, Lee reasoned the Federal center was the weak point, and he assaulted it with much of his remaining strength. But "Pickett's Charge" became a bloody, infamous failure. The next day, the beaten Confederates retreated to Virginia.

The Union victory in the war's bloodiest and most famous battle snapped Lee's winning streak and emboldened the north. Months later, Lincoln commemorated the victorious fallen as defenders of freedom and democracy in the Gettysburg Address, one of the great speeches in American history.

Overland campaign (May 4 - June 24, 1864)

The NPS states that Ulysses S. Grant took command of all Union armies in 1864. With Vicksburg now in U.S. hands, the defeat of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was of supreme importance. The American Battlefield Trust says Grant kept General George Meade on as commander of the Army of the Potomac, but camped with and directed him. The goal: sink the army's teeth into Lee, and don't let go. Unlike Grant's predecessors, he wouldn't run away after getting his nose bloodied; instead, he would disengage and resume the advance towards Richmond, knowing Lee would have no choice but to block him. Each clash was an opportunity to crush, or at least further weaken, Lee.

But Lee was Grant's most capable opponent. History says he parried blows at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor. Each time he used either thick woods or entrenchment to negate Grant's numerical advantage and inflict frightening casualties. But his own army was badly mauled too — and unlike the North, he couldn't easily replace his losses.

The Great Courses Daily describes the Overland campaign as the "showpiece confrontation of the war," with huge stakes, featuring the most important armies and generals duking it out in the area close to each capital. The war was reaching a bloody, horrifying climax. But the end was near.

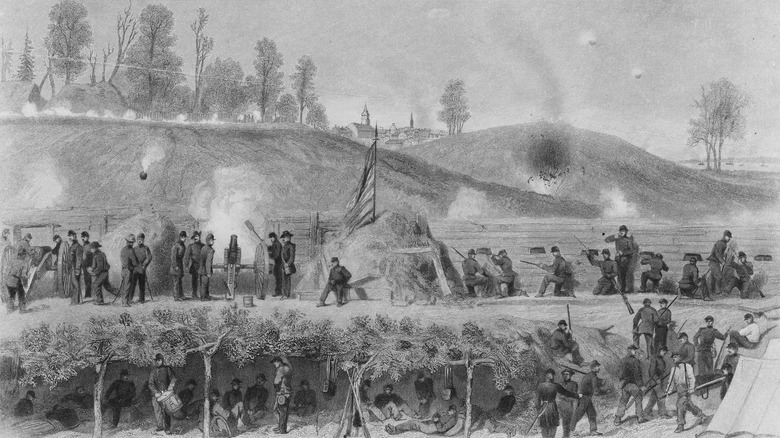

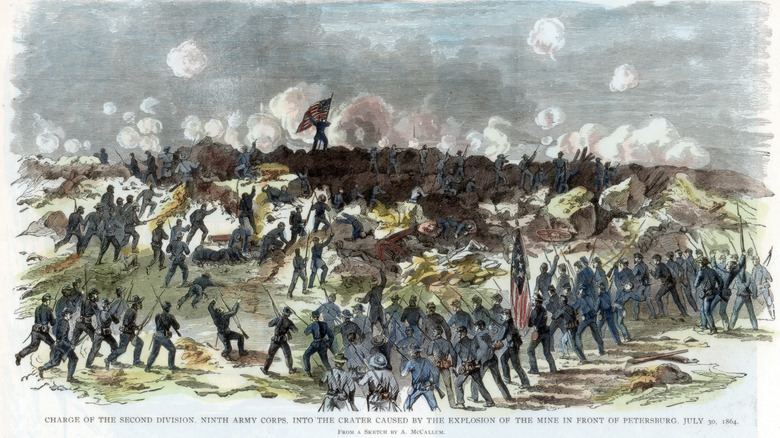

Siege of Petersburg (June 9, 1864 - April 3, 1865)

American History Central notes that the Overland campaign — Ulysses S. Grant's bloody slog against Lee in late spring 1864 — shocked an exhausted North. It was clear that more appalling bloodshed, with few decisive victories to show for it, would not bode well for Abraham Lincoln's re-election later that year.

But the horrors were just beginning. Historic Petersburg writes that Petersburg, south of the capital of Richmond, was a vital railroad hub, without which neither Richmond nor Robert E. Lee could receive supplies. Its fall would mean Richmond's fall and the collapse of Lee's army. The article notes that Lee predicted Grant's next move as early as June 1864, when he told Major General Jubal Early, "We must destroy this Army of Grant's before he gets to the James River [near Petersburg and Richmond]. If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time."

He was right. The Overland campaign ended with Grant's 100,000 man army charging towards the city. Its 20,000 defenders erected earthworks while Lee raced to their aid (via History). Grant, realizing those fortifications would be hard to assault, settled in for a siege. For nine months, Lee's army, stretched to breaking point along a 40 mile front (via History), withered due to desertion, attrition, and starvation. When the Union finally broke through in April 1865, they chased Lee to Appomattox and quickly forced him to surrender his tiny, exhausted army (via Constition Center). The war was all but over.

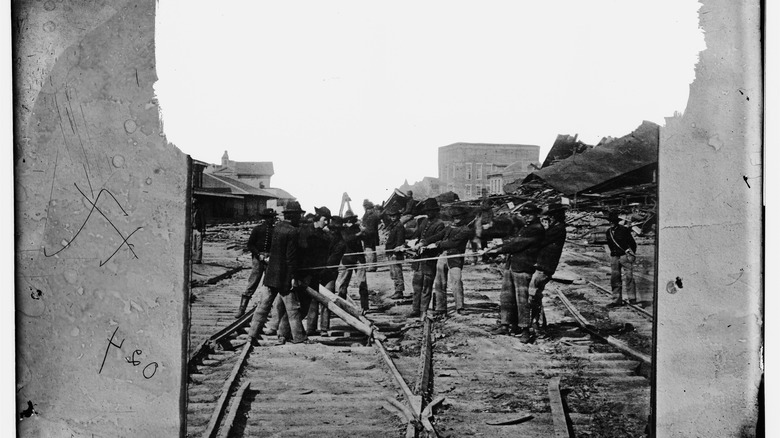

Sherman's march to the sea (November 15 - December 21, 1864)

By the second half of 1864, the twin sieges of Atlanta and Petersburg were going nowhere fast but racking up horrible body counts. Constituting America notes that Abraham Lincoln's prospects for re-election that November looked dim. But all was not lost for the North. In fact, significant breakthroughs were just around the corner. General William T. Sherman's larger army eventually broke through to Atlanta and took the city, prompting what the same article describes as "jubilation" in the north.

Now Sherman had to finish the job. While Ulysses S. Grant hammered away at Robert E. Lee in Virginia, Georgia Encyclopedia says Sherman sought to break the back of the Confederacy by boldly abandoning his supply lines and marching from Atlanta to the Georgian coast, living off the land and wreaking as much havoc as possible on the way. His forces liberated enslaved people, tore up railroads, and used maximum destructive force against civilians, knowing that they were destroying the Confederate war effort.

It's important to note that although unnecessary cruelty did occur, The American Battlefield Trust says the March to the Sea was far from the slaughter it's sometimes made out to be. Plus, it worked: Britannica notes that destruction of farmland hurt the entire rebel war effort, and news of it caused desertions in Lee's army to skyrocket. Once he reached the sea, Sherman turned north, carving through the Carolinas, but the war would end before he got to Virginia.

Battle of Nashville (December 15-16, 1864)

Few generals underwent as drastic a change in reputation over the course of the war as John Bell Hood. The American Battlefield Trust says the Confederate commander was a force to be reckoned with as a corps commander under Robert E. Lee, but that on his own, he produced nothing but disaster for the South.

According to History, Hood abandoned Atlanta to the besieging army of William T. Sherman, and he tried to draw him away from the Georgian heartland by marching north, in the hopes that the Union general would chase him. But Sherman didn't take the bait. He began his March to the Sea (via American Battlefield Trust) and ordered General George H. Thomas to handle Hood's attack in Tennessee.

Hood did just about nothing right. The American Battlefield Trust says that his frontal attacks at Franklin produced a mutilating defeat. Such losses should have thrown him over to the defensive. But inexplicably, despite being outnumbered more than ever, he stuck to the attack and caught up to George Thomas again at Nashville. Here, it was Thomas' turn to strike. Some troops distracted the Confederates while the bulk of Thomas' force swung around the flank and — attacking fortified high ground, mind you — crushed Hood's remaining men. The defeat was so complete and overwhelming that it effectively ended all large-scale fighting in the area for the rest of the war, and it earned Thomas the official thanks of Congress (via National Park Service).