The Largest Pharmaceutical Settlements In U.S. History

In September 2021, Purdue Pharma was ordered to pay more than $4 billion as part of a settlement deal. But this settlement deal was overturned the following December, due to the fact that the protections that it offered weren't "permitted under the bankruptcy code." But even if the settlement had gone through, it still would have barely made it into the top three largest pharmaceutical settlements in American history.

In most of these pharmaceutical settlements, the main company often tries to spread the responsibility onto its subsidiaries, like Pfizer with Pharmacia & Upjohn or Johnson & Johnson with Janssen. For brevity's sake, this piece will note only the parent companies associated with the respective settlements.

And even though many of these figures seem astronomical, more often than not, these huge penalties are just used to send a message to the pharmaceutical industry and they amount to just a fraction of the company's yearly profits. These are the largest pharmaceutical settlements in U.S. history.

Manufacturing deficiencies: $750 million

Between 2001 and 2005, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) manufactured the anti-nausea medication Kytril, the anti-infection ointment Bactroban, the antidepressant Paxil CR, and the diabetes drug Avandamet at a manufacturing facility in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Although GSK closed the manufacturing plant in 2009, in 2010, GSK pled guilty to manufacturing the drugs at the facility without always using the FDA-approved mix of active ingredients. GSK agreed to pay $750 million as part of their criminal and civil settlements.

According to the Department of Justice, there were also "longstanding problems of product mix-ups, which caused tablets of one drug type and strength to be commingled with tablets of another drug type and/or strength in the same bottle." And none of these accusations were new to GSK.

In 2002, GSK quality control manager Cheryl Eckard, who ended up whistleblowing on GSK, was assigned to lead an investigation into the manufacturing plant in Cidra, Puerto Rico. In "Phake," Roger Bate writes that Eckard not only discovered product mix-ups but found that "drugs produced at Cidra were being contaminated with bacteria by poor employee manufacturing practices and tainted water." Although Eckard immediately told her superiors and "recommended immediate action," GSK did nothing, and after repeatedly complaining, Eckard was fired, with "down-sizing" being given as the excuse.

Aranesp: $762 million

In 2021, Amgen Inc pled guilty to improper marketing practices involving the anemia drug Aranesp, also known as darbepoetin alfa. According to Reuters, Amgen agreed to pay $762 million as part of its criminal and civil settlement.

Although Aranesp was approved to treat anemia as a side effect of chemotherapy, Amgen promoted Aranesp to treat anemia in cancer patients who weren't receiving chemotherapy. Sales representatives reportedly weren't even aware that they were promoting the drug for off-label uses.

The New York Times also reports that "Amgen promoted using larger but less frequent injection of Aranesp than stated in the label as a way of making the drug more attractive to doctors and patients." Amgen tried to get FDA approval for the larger dose, but they were denied due to an "inadequate" study. Nevertheless, Amgen continued to promote the larger dose, Acting U.S. attorney Marshall Miller stated that Amgen was "pursuing profits at the risk of patients' safety."

Lupron settlement: $875 million

TAP Pharmaceutical Products, a joint venture between Abbott Laboratories and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, paid $875 million to settle criminal and civil charges in 2001 and pled guilty to a conspiracy to defraud Medicare and Medicaid. The New York Times reports that at the time, the settlement was "the largest for health care fraud."

According to KHN, TAP was accused of inflating average wholesale prices of the prostate cancer drug Lupron, also known as leuprorelin, in order to "increase sales and profits." Sales representatives reportedly paid kickbacks to doctors for prescribing Lupron in addition to giving doctors free samples and "then help[ed] them get government reimbursements at hundreds of dollars for each dose." Several doctors were also charged with health care fraud. Meanwhile, countless elderly patients were paying more than if their doctor had prescribed "a competitor's lower-priced product with the same effectiveness," writes UPI.

President of TAP Thomas Watkins said that although TAP "fundamentally disagreed" with the allegations, they went through with the settlement because the federal government threatened to halt all reimbursements for Lupron.

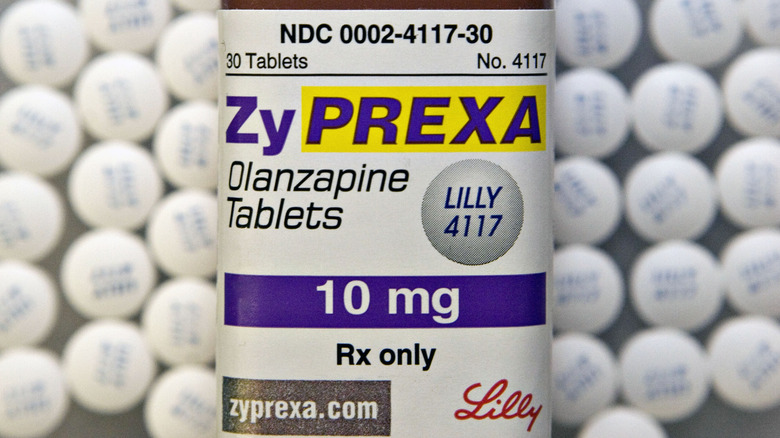

Zyprexa settlement: $1.4 billion

Eli Lilly and Company introduced the antipsychotic Zyprexa, also known as olanzapine, to the market in 1996. Although Zyprexa was only approved for the treatment of bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia, Eli Lilly started promoting Zyprexa off-label for the treatment of "agitation, aggression, hostility, dementia, Alzheimer's dementia, depression, and generalized sleep disorder."

According to the Department of Justice, Eli Lilly instructed their sales representative to promote off-label uses in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. During one sales pitch, the Zyprexa was said to reduce "nursing time and effort" by helping sedate "unruly nursing home patients," writes The New York Times. In January 2009, Eli Lilly pled guilty and agreed to pay $1.415 billion towards a criminal and civil settlement for the off-label promotion of Zyprexa.

Zyprexa not only increases the risk of heart failure and pneumonia in elderly patients, but in 2004 the American Diabetes Association found that Zyprexa "caused diabetes more" compared to other antipsychotic drugs. Eli Lilly reportedly spent an additional $1.2 billion to settle lawsuits from 31,000 people who developed health problems from Zyprexa. Eli Lilly also knew of the risks associated with Zyprexa and spent almost a decade downplaying the risks.

Depakote settlement: $1.5 billion

In 2012, Abbott Laboratories pled guilty to unlawful promotion of the anticonvulsant Depakote, also known as sodium valproate. Abbott agreed to pay $1.5 billion as part of a criminal and civil settlement. According to the Department of Justice, Abbott promoted the use of Depakote "to control agitation and aggression in elderly dementia patients and to treat schizophrenia" despite the fact that neither of these was approved by the FDA.

Abbott also maintained a "specialized sales force" that was specifically trained to market the drug in nursing homes from 1998 to 2006. Abbott sales representatives reportedly claimed that Depakote could help nursing homes "avoid the administrative burdens and costs of complying with OBRA [the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987]." The New York Times reports through this, Depakote was promoted as a way for nursing staff to "sedate patients without running afoul of a federal law intended to prevent overuse of certain medications."

Although the illegal prescriptions didn't result in any deaths, U.S. Attorney Timothy Heaphy of the Western District of Virginia maintained that "this is an elder abuse case," CNN reports.

Risperdal settlement: $2.2 billion

Although Risperdal, also known as risperidone, is used as an antipsychotic, Johnson & Johnson was accused of illegally marketing the drug to elderly people, people, and people with developmental disabilities. The New York Times writes that while Johnson & Johnson pled guilty in 2013 to a criminal misdemeanor and "improperly marketed Risperdal to older adults for unapproved uses," it didn't admit to promoting the drug's use in children and disabled people. The criminal and civil settlement amounted to $2.2 billion.

According to the Department of Justice, Johnson & Johnson was aware of the health risks, including an increased risk of diabetes and stroke, that Risperdal posed to elderly people but these risks were downplayed. Johnson & Johnson also reportedly "illegally market[ed] the drugs as a way to control patients with dementia in nursing homes and children with certain behavioral disabilities."

Reuters reports that thousands of additional lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson were reportedly settled in 2021, which claimed that Risperdal caused men to develop excessive breast tissue. Johnson & Johnson reportedly spent $800 million "in expenses in connection" with the settlement. Johnson & Johnson also reportedly paid kickbacks to Omnicare, a pharmacy that specialized in nursing homes, to promote "Risperdal and other J&J drugs."

Bextra settlement: $2.3 billion

In September 2009, Pfizer Inc. pled guilty to misbranding Bextra, also known as valdecoxib, with the intent to defraud and agreed to pay a settlement of $2.3 billion. At the time, this was considered "the largest health care fraud settlement" in American history. The settlement included a criminal fine of $1.95 billion, "the largest criminal fine ever imposed" in America, as well as a $1 billion civil settlement. However, despite the fine being described as a record amount, CNN writes that Pfizer only lost about three months' worth of profits at the time.

Bextra was approved by the FDA in 2001 for arthritis and menstrual cramps and even though it wasn't approved for "acute pain," Pfizer told its sales representatives to claim that it could treat "acute and surgical pain." Increased doses were also encouraged even though "kidney, skin, and heart risks increased with the dose."

The New York Times reports that Pfizer pulled Bextra from the market in 2005 for the heart and skin risks, but that wasn't the only drug that they'd illegally pushed for off-label uses. The civil settlement paid by Pfizer also involved the antipsychotic Geodon, the antibiotic Zyvox, and the nerve pain drug Lyrica. Pfizer allegedly paid kickbacks to health care providers to prescribe these drugs for off-label uses. At the time, this was "Pfizer's fourth settlement over illegal marketing activities since 2002."

Actos settlement: $2.7 billion

When Takeda Pharmaceutical Company began selling the diabetes drug Actos, also known as pioglitazone, to control high blood sugar, it was initially considered to be "much safer than other remedies." But by 2015, Takeda had agreed to pay $2.4 billion to settle thousands of lawsuits that alleged that Actos causes bladder cancer, writes The New York Times. The amount was expected to rise to $2.7 billion if 97% of plaintiffs decided to opt-in and involved up to 9,000 bladder cancer claims.

Takeda didn't admit liability and instead stated that they'd settled to "reduce the uncertainties of complex litigation." But during various lawsuits, including one in Louisiana where a jury ordered Takeda and Eli Lilly to pay $9 billion (later reduced by a judge to $36.8 million), it was revealed that Takeda knew of the cancer risks and deliberately obscured them. Carey Gillam writes in "The Monsanto Papers" that during the lawsuits, "it was revealed that the company knew even before the drug was approved that a study of rats dosed with the drug showed an association with bladder cancer." According to Drugwatch, even one of Takeda's own 5-year interim studies showed an increased risk of bladder cancer in people who took Actos for over a year.

Despite the fact that Actos was banned in France and Germany and numerous studies linked Actos to an increased risk of bladder cancer, Takeda never issued a U.S. recall of the drug.

The GlaxoSmithKline settlements: $3 billion

When GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) settlements agreed to pay $3 billion in a civil settlement regarding allegations of pricing fraud in 2012, it wasn't even the largest settlement they'd ever had to pay. In 2006, they agreed to pay a $3.4 billion settlement to the IRS, "the largest in IRS history." But in 2012, GSK was facing a bit more than just issues regarding "transfer pricing."

The New York Times reports that the criminal charges were regarding promotion of the antidepressants Paxil and Wellbutrin and "failing to report safety data" about the diabetes drug Avandia, and the civil charges were for "improper marketing of a half-dozen other drugs." This includes things like publishing medical journal articles that "misreported data" as well as paying for doctors to take trips to Bermuda and Jamaica, passing them off as conferences.

In the end, The Guardian writes that GSK ended up admitting to "bribing doctors and encouraging the prescription of unsuitable antidepressants to children." According to the Department of Justice, GSK pled guilty to two counts of introducing misbranded drugs into interstate commerce and one count of failing to report safety data and agreed to pay $1 billion towards the criminal plea agreement. GSK also agreed to pay $2 billion "to resolve its civil liabilities" under the False Claims Act.

Fen-phen settlement: $3.75 billion

American Home Products (AHP) started manufacturing and marketing Pondimin, their brand name for fenfluramine, as a diet pill in 1989. But the drug really became popular in 1992, when Dr. Michael Weintraub suggested mixing fenfluramine with phentermine, another weight loss drug, could lead to faster weight loss, according to The New York Times. This was referred to as fen-phen.

Another diet pill known as Redux, the AHP brand name for dexfenfluramine, was also approved by the FDA in 1996. But then the following year, both Pondimin and Redux were suddenly pulled from the market because a Mayo clinic study in July 1997 showed that 24 people "with no prior heart conditions" ended up with heart valve damage after taking fen-phen, according to the California Western Law Review. This wasn't the first time fen-phen was shown to be dangerous. Health Affairs writes that fen-phen's link to primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH) was revealed in August 1996, but the report by French epidemiologist Lucien Abenhaim was "minimized by drug companies and the FDA."

It's estimated that roughly six million people in America took the diet drugs, and up to 33% may have ended up with serious heart problems. Over 9,000 lawsuits were filed, with one Texas jury even awarding a former fen-phen user $23.3 million, according to CNN. And in 2006, AHP ended up agreeing to pay $3.75 billion to settle a class-action lawsuit. However, this settlement only applied to those with heart valve problems, not those with PPH.

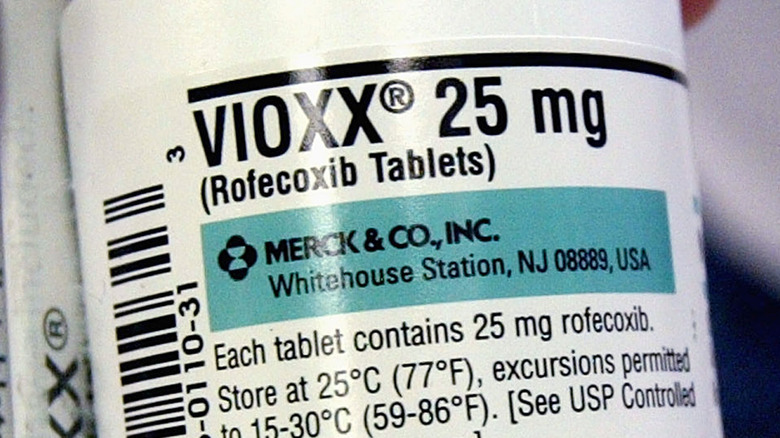

Vioxx settlement: $4.85 billion

The FDA approved Vioxx, Merck's nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory painkiller for the treatment of osteoarthritis, in May 1999. But a few months before the FDA approval came through, Mereck launched the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research study (VIGOR) in January 1999. According to the BMJ, the study was meant to prove that Vioxx, also known as rofecoxib, had fewer gastrointestinal side effects than naproxen, another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

In the study of over 8,000 people, researchers learned that although Vioxx did decrease the risks of "gastrointestinal events," there was also evidence of an increased risk of a heart attack. However, the published VIGOR study "obscured the cardiovascular risk." Although Dr. Jeffrey Drazen, editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, later said that the authors of the VIGOR study had "withheld critical data on the cardiovascular toxicity of Merck's drug Vioxx," none of the authors acknowledged any fault in the study.

Despite the link between cardiovascular incidents and Vioxx, Merck kept the drug on the market for five years. During that time, it's estimated that between 88,000 and 140,000 heart attacks were caused by Vioxx, per New Scientist, resulting in at least 38,000 deaths. Merck finally withdrew Vioxx from the market in September 2004, according to NPR, and by 2007, there were over 27,000 lawsuits against Vioxx for causing heart attacks and strokes. Merck paid a civil settlement of $4.85 billion, though they did "not admit causation or fault."

A nationwide settlement: $26 billion

In July 2021, the largest pharmaceutical settlement in U.S. history was announced. Totaling $26 billion, the settlement came in response to the allegations that drugmaker Johnson & Johnson and U.S. drug distributors McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen "helped fuel a deadly nationwide opioid epidemic," writes CNBC. The accusations ranged from "lax controls" that allowed for the illegal sale of painkillers to "downplaying the addiction risk" in opioid marketing. All four companies have denied the allegations.

The settlement proposal stipulates that Johnson & Johnson pays $5 billion over nine years while the U.S. distributors pay a combined $21 billion over 18 years. The New York Times reports that as part of the settlement, distributors would also have to establish "an independent clearinghouse to track and report one another's shipments." The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma also reached their own $75 million settlement with the U.S. distributors.

For the settlement to go through, a majority of states and their municipalities have to sign up. The deadline to sign up for the settlement was extended to January 26, 2022, and on the day of the deadline, Reuters reported that "90% of local governments nationwide" opted to participate in the settlement. Forty-five states also agreed to settle with the U.S. drug distributors and 44 states agreed to settle with Johnson & Johnson. And if the settlement is finalized, states and local governments have to "drop lawsuits against the companies and also pledge not to bring any future action."