The Untold Truth Of Pompey The Great

Some historical figures like Julius Caesar or Cleopatra have all the luck. They get the spotlight consistently, whether we're talking dramatic plays, documentaries, or the textbook treatment. They also become regular parts of pop culture, enjoying shoutouts on social media, in songs, and through Halloween costumes. While the real-life people these legends are based on may fall well short of their exaggerated reputations, something about their personas still endears them to the public.

Ultimately, few ancient individuals enjoy this type of prestige, however. Most historical figures are lucky to get typecast in supporting roles or as "bad guys and gals." Next to nobody dresses up like these characters for trick or treating, and their names remain largely unspoken. Pompey the Great, despite the over-the-top moniker, falls into this second category. If and when we read mention of his name or see him on the silver screen, it's in the context of his tempestuous political relationship with Julius Caesar, the general-turned-self-proclaimed-dictator.

That said, Pompey the Great was far from a stick in the mud. This ambitious Roman showed himself effective both on the battlefield and in the game of politics. And his eventual assassination represented an epic betrayal rivaled only by the karma his successor, Julius Caesar, received on the Ides of March. Here's what you need to know about this underrated Roman leader.

Pompey enjoyed a typical Roman education

Raised for greatness, Pompey enjoyed a typical Roman upbringing designed to prepare him for public service (via Britannica). This broad-ranging education required cultivating his military prowess and political ambitions. Besides stoking these interests and talents, he received instruction in Greek philosophy and literary classics. It meant learning ancient Greek and establishing close friendships with various Greek intellectuals.

According to Penn State, his father, Pompeius Strabo, eventually appointed Pompey to his staff, which helped the future military commander and civic ruler learn practical lessons about leadership and the ins and outs of the Roman Republic's politics. During his lifetime, Strabo worked hard to enlarge the family's landholdings in Picenum, and he chose his political alliances with care. When civil war broke out between two rival generals from 88 to 87 B.C., Strabo sided with Gaius Marius over Lucius Sulla.

The faction that supported Marius called themselves the Marians, and Gaius Marius represented the first Roman general to gain political support through the soldiers he commanded. Ironically, this model inspired by Marius would both help and hinder Pompey throughout his career. At times, he would assume the role of a beloved general, and at others, he had to deal with military figures like Julius Caesar who also sought power through the sword, as reported by Britannica.

He played a murky role in a mutiny against Cinna

According to Britannica, Pompey did a disappearing act following his father's death. And unlike Pompeius Strabo, who fought in support of the Marians, Pompey would re-emerge on the opposite side of the confrontation, supporting Lucius Sulla. Along the way, he got embroiled in a mutiny plot, although the depth of his involvement remains up for debate.

It all started when reports surfaced that Pompey had gone missing from Lucius Cornelius Cinna's army en route to the Balkans to rout Sulla (via Britannica). Cinna led the army and served as political head of the Marian party, having succeeded Gaius Marius. The disappearance of Pompey sent shockwaves through the legion.

In "Pompey the Great," Pat Southern suggests that Pompey likely disappeared out of apprehension that Cinna would try to murder him. Southern claims Cinna's violent designs on Pompey pre-dated the death of Pompey's father. Soon, the rumor took a darker shade, as Cinna's ranks assumed Pompey's absence meant their leader had already murdered Pompey. The spooked men soon wrested power from Cinna, murdering him in 84 B.C.

Pompey resurfaced with Sulla in Picenum

After the messy business of Lucius Cornelius Cinna's mutiny, Pompey re-emerged at the head of three legions in Picenum in 83 B.C., as reported by Britannica. He allied with Lucius Sulla to seize Rome and Italy back from the Marians. Evidently, in the face of possible assassination by Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Pompey had come to realize the value in allying with his father's former enemy, Lucius Sulla.

During the second civil war for the Roman Republic, Pompey earned the nickname "Magnus" (literally "the great") from the soldiers he commanded. They called him this in recognition of his brutal destruction of enemy forces during two "lightning campaigns" in Africa and Sicily. Besides "Magnus," the troops also referred to Pompey as "Imperator," which must've puffed up his political ambitions. However, according to the History Cooperative, his enemies called him the "teenage butcher" because of the atrocities he committed on the battlefield.

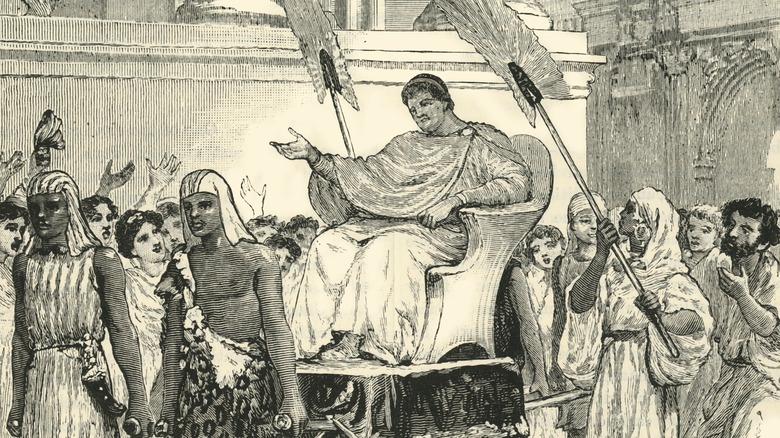

Invigorated by his increasing popularity, Pompey demanded Sulla throw him a triumph in Rome. Pompey's loyal troops made sure it was an offer that Sulla couldn't refuse. Soon, the streets of Rome commemorated Pompey's military prowess. What's more, Sulla felt compelled to honor Pompey's title of "Magnus," making it official. A strategic marriage to Sulla's stepdaughter, Aemilia, cemented his military role and furthered his political ambitions (via Shelley P. Haley's "The Five Wives of Pompey the Great").

His military career furthered his political ambitions

Like his father before him, Pompey gained renown for leading highly successful military campaigns (via Britannica). But the reconquest of Spain proved challenging even to the experienced soldier. It also drained the Roman Republic of its resources. Nevertheless, Pompey and his troops ensured a favorable ending for his nation.

He made rehabilitation and reconciliation vital components of this campaign, but he also ensured that his personal political ambitions got furthered in the deal. Soon, his influence extended from Spain to Gaul and into northern Italy. According to Pat Southern's "Pompey the Great," he commemorated his successes in Spain by erecting a monument in the Pyrenees near the Mediterranean Coast. Because the reconquest of Spain was an extension of the civil war and involved fighting fellow Romans, Pompey made no mention of the enemy on the plaque. But the monument did do a fine job of celebrating his exploits and those of his soldiers.

Like other Roman generals, Pompey faced recall to Rome and the disbanding of his army. But luck prevailed in the nick of time, permitting him to return to the "Eternal City" in full command of his army. A slave named Spartacus had amassed an army, almost by accident, that now cut through Roman counter offenses with shocking ease.

Pompey used Spartacus' slave revolt to gain political power

According to Britannica, Pompey returned to Italy with his men to assist in putting down a slave revolt led by Spartacus before his political rival Marcus Licinius Crassus could take all the credit. He had apparent designs in mind, namely securing a triumph and election to the consulship, both of which came to fruition in 70 B.C.

But Pat Southern's book "Pompey the Great" explains that more to this transaction existed than meets the eye. Spartacus' initial rebellion started in 73 B.C. when a group of gladiators compelled to fight in Capua broke free from their ranks, escaping to the hinterlands of Mount Vesuvius. There, they intended to slip away quietly, returning to their homelands. But in a surprising turn of events, other slaves heard of Spartacus' exploits, inspiring them to escape and join his ranks. Soon, a veritable army had assembled. One capable of destroying the various armies the Roman Republic sent to quell the rebellion.

Southern explains that Crassus engaged the slave army with six legions, setting up blockades across the Italian peninsula. But he couldn't gain the upper hand. So, he wrote letters appealing to Pompey in Spain and Lucullus, who fought against Mithradates. An official summons from the Senate soon followed these appeals. Long story short, Pompey eventually took all credit for putting down Spartacus's army, and Crassus lamented his decision to seek assistance (via Southern).

He climbed the ladder of Rome's highest ranks

Pompey strategically chose military campaigns, which he hoped would further his political ambitions, according to Britannica. But Pat Southern notes in "Pompey the Great" that he still struggled to win the support of the Senate and the people. Fortunately, the Roman general had a trick up his sleeve (or rather, his toga) that would at least ensure the public appreciated and acknowledged his many achievements, holding more triumphs. In September 61 B.C., he regaled the people with feasting, processions, and entertainment on a grand scale at his third triumph.

The festivities left such an impression people talked about them for years. Not only were the Romans impressed by the over-the-top nature of his third triumph, but they also acknowledged the rarity of staging three triumphs at all. These triumphs highlighted Pompey's role as a conqueror of three continents: Africa, Asia, and Europe. They also announced his ascendancy to the highest ranks of Roman public life.

Of course, nothing lasts forever, and this proved no less true when it came to Pompey the Great. As the ancient author Plutarch would later reflect, Pompey would've done better to die or disappear at the height of his power because the events that followed would tarnish his reputation for generations of Romans (via Southern).

Pompey feared Caesar's growing prestige

Despite ample prestige and power, Pompey soon had a problem on his hands (via Britannica). A general named Julius Caesar was growing in political and military esteem. Ironically enough, the trajectory of Caesar's career held a marked resemblance to that of Pompey's. What's more, Caesar brought Pompey's power base under his sphere of influence through careful strategizing, as reported by History.

Perhaps this explains why Pompey experienced so much trouble attempting to quell the ambitious commander's rise to glory, fame, and dangerous popularity among his troops. To add insult to injury, Pompey divorced his wife Mucia due to her alleged adulterous relationship with Caesar. Despite these tensions, though, neither Caesar nor even Marcus Licinius Crassus represented Pompey's real political enemies. Both generals merely vied for the same spotlight in the Roman rat race.

Pompey's real problems stemmed from the Optimates, a group of aristocrats that dominated the Senate, posing actual obstacles to Pompey's objectives. The Optimates took every opportunity to outmaneuver Pompey politically, especially while he served overseas with his army. Yet, Pompey avoided open opposition from the Optimates by allying with popular elements of the Senate. Never one to start a revolution, he may have initially underestimated the depths the Optimates would go to, to render him politically impotent. But he wouldn't make this mistake twice.

He used Caesar and Crassus as political means to an end

Pompey needed to stabilize the faltering Roman Republic and counterbalance the ambitious Optimates (via Pat Southern). So, he formed a secret and surprising pact with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Julius Caesar, according to History. Together, the three men created what many historians refer to as the "First Triumvirate." The selection of this name by historians cleverly presaged the later hierarchy established by Marc Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian. But comparing this first unofficial triumvirate with the official one following Julius Caesar's assassination is problematic. The number one difference between these two political entities remains the very informal and unofficial nature of the first.

Rumors of in-fighting between Pompey and Crassus would also plague the group. Some speculated that Caesar and Crassus secretly worked behind the scenes to undercut Pompey at every turn. But Southern argues that Caesar acted as a peacemaker, attempting to smooth the rough edges of the relationship between the other two generals-turned-politicians. What's more, ancient sources support the notion that the three sealed their deal with an oath, although what this oath entailed remains a mystery.

According to Britannica, the most powerful bond between members of the triumvirate involved nuptials, however. Caesar's beloved daughter, Julia, married Pompey, providing a welcome balm of union between the two men, as reported by History. While power struggles and personal interests still influenced their decisions, the men generally tried to avoid each other's toes, which made for fleeting stability and peace.

Power struggles strained Pompey's First Triumvirate

Forces outside each man's control would eventually bring the tenuous, perhaps even feigned, harmony of the so-called "First Triumvirate" to a boiling point (via History). It started with the death of Julia, Pompey's wife and Caesar's daughter, in childbirth in 54 B.C. Cherished by her father and husband alike, the tragedy of her passing didn't immediately estrange the men. But it eroded their closeness over time (via Pat Southern's "Pompey the Great.") In 53 B.C., Crassus suffered defeat and death in Mesopotamia, producing a power vacuum.

The alliance was visibly and irreparably damaged. But chinks in its armor had existed from the get-go. These transformed into fissures as Caesar enjoyed unparalleled success on campaigns in Gaul (modern-day France) and the Germanic regions. His achievements created a festering sense of resentment in Pompey that burst to the surface after Crassus' death. In a decisive move to neutralize the threat posed by Caesar, Pompey allied with the general's domestic enemies. Next, he ordered the decorated military leader to disband his army and return to the capital.

Caesar's political astuteness had long preserved him when it came to Rome's ruthless governance, and he wasn't about to fall for what amounted to a death sentence. With his back against a wall, Caesar's resourcefulness and fearlessness kicked in as he rallied his troops to the cause of self-preservation. The Roman Republic sat poised on the edge of a blade as civil war loomed ahead.

He couldn't avoid civil war

After Pompey rejected another marriage alliance offered by Julius Caesar, no bridge could traverse the rift between the two generals, according to Britannica. Chaos broke out in the "Eternal City" as Romans feared for the future. Some suspected Pompey sought a dictatorship, and violence from various political factions exploded, culminating in the destruction of the Senate by arson.

As Rome devolved into mob violence, Pompey's paranoia about Caesar grew unrestrained. He passed various pieces of legislation that Caesar's allies came to see as explicitly designed to halt the general's political plans following the end of his campaign in Gaul. Soon, the Senate fractured down the middle between those who supported Pompey and those who threw their fate in with Caesar's.

Unable to ignore the situation, the Senate declared a state of war on January 7, 49 B.C. A few days later, Caesar upped the ante by crossing the Rubicon with his loyal troops, per National Geographic. Pompey decided to flee Rome and Italy, but Caesar's quick invasion nearly thwarted his plans. Caesar realized that as long as Pompey lived, he would remain dogged at every turn by his son-in-law-turned-nemesis. So, he stubbornly pursued Rome's former leader across Spain, Greece, and eventually into Egypt, as reported by History.

Pompey overplayed his hand

According to Britannica, Pompey escaped to Dyrrhachium (modern-day Albania) before pursuing Julius Caesar's forces into Thessaly. There, his men united with the Senate's army led by Scipio, which put Caesar in a precarious position. Pompey set up a naval blockade to starve Caesar's forces and to prevent the introduction of reinforcements. But Pompey also faced pressure from those allied with him, namely the Optimates, who wanted to see a swift resolution to the conflict.

As a result, Pompey pushed his hand, engaging Caesar's men in battle on the plains of Pharsalus in 48 B.C. He failed to realize that years of campaigns in Gaul and Germany had rendered Caesar a military genius. The unrivaled commander dealt Pompey's forces a fatal blow despite the handicaps he faced.

With Caesar's forces rushing to storm his camp, Pompey narrowly escaped. A lightning-fast pursuit by the general himself forced Pompey to run for his life, getting cut off from his naval fleet in the process. Left with few options, Pompey sailed to Egypt, where he sought refuge and assistance from his former client, Ptolemy. Met offshore in Alexandria by Ptolemy's men, they pretended to head towards the shore before one in the crew viciously stabbed Pompey the Great (via Pat Southern). The assassin beheaded the once-great general and preserved this memento in a pickle jar, according to a grisly tradition.

Pompey's legacy remains mixed and underrated

Pompey would leave a mixed legacy, according to Pat Southern's "Pompey the Great." Britannica notes he died the wealthiest man of his generation, having invested wisely in the ancient equivalent of real property, landed estates.

Some historians have also noted that Pompey was one of Rome's greatest architects and a capable general who subdued Mediterranean pirates and forces on three continents during his military career. But Julius Caesar ultimately outclassed and eclipsed his many achievements in life (as Pompey had rightly feared).

Cambridge points out that Pompey the Great's ancient fame has made him feel remote and distant to those who study his life today. But it's worth noting that by all accounts he was a loving family man who showed great devotion to two of his wives, Julia and Cornelia. His sons remained loyal to him long after his death, refusing to denounce their lineage despite the fact it came with plenty of baggage in Caesarian Rome. Above all else, Pompey's destiny became inextricably linked with the Roman Republic, a political institution buried along with the controversial leader.