Walt Disney's Time With The FBI Explained

While Americans cringe at the censorship conducted by leaders abroad, we often forget our own foray into conspiracy-riddled, quasi-fascist persecution of alleged "political detractors" (and ordinary citizens) during the Cold War. Most notably, Congressman Joseph McCarthy and his colleagues spearheaded a paranoid campaign against a (largely nonexistent faction) of "secret" Communists. With the help of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and dozens of others drunk with Cold War hysteria, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed dozens of Hollywood actors and writers, government officials, political activists, and everyday Americans accused of being secret "Communists" or spies.

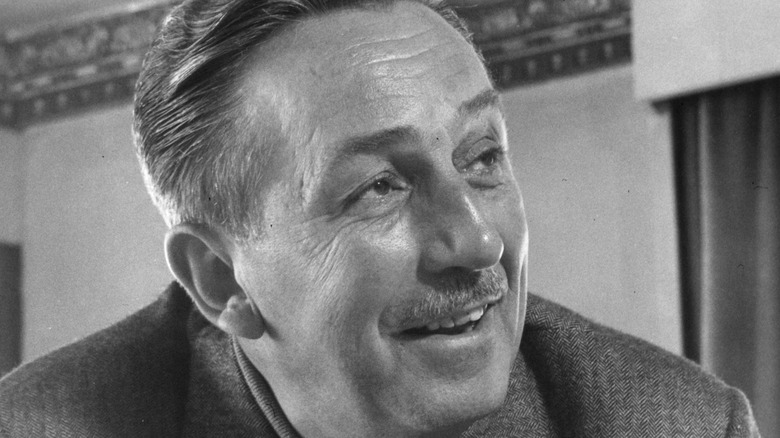

This could not have been possible without dozens of informants, which the FBI solicited by establishing relationships with a variety of individuals willing to decry their counterparts and serve as Hoover's eyes. Among McCarthy's many informants was none other than Walt Disney. From 1940 to 1966 (per The New York Times), the media mogul and founder of the Walt Disney Company was not only pioneering cartoon animation techniques but reporting his colleagues to the FBI's J. Edgar Hoover. In his reports referred to the House Un-American Activities Committee, Disney accused several of his Hollywood contemporaries (known actors, producers, directors, writers, and union heads — the specific names have been redacted) of being "Communists," referring them for investigation by McCarthy. According to Reader's Digest, Disney was such an active informant that the FBI's Los Angeles office awarded him the full status of S.A.C. Contact (Special Agent in Charge) in 1954.

The Color of Money Is Red

Marc Eliot's unofficial biography, "Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince," revealed Disney's secret role as an FBI informant (per The New York Times). The 570-page FBI file on "Walter Elias Disney" (via FBI Vault) portrays the man who voiced squeaky-clean Mickey Mouse as ruthless, vindictive, and dogmatic. According to History On This Day, the earliest communications between Disney and J. Edgar Hoover (then-director of the FBI) date to 1936, although he did not begin informing in any official capacity until 1940. Although his right-wing politics were common knowledge, Disney used Red Scare hysteria — and his status as an informant — to eliminate anyone who stood in his way.

One year after taking on this role, Disney would even report his own employees to the FBI. When Disney animators went on strike in 1941 demanding better wages, Disney used his role as an informant to report them for engaging in "Communist agitation," as reported by The New York Times. (Rather than listening to his employees' concerns, he even embarked on a campaign to defame them. Disney took out a full-page ad in "Variety" magazine baselessly alleging the striking workers were secret Communists — a red-letter tactic for the apex of the Red Scare.) Disney would later go so far as to publicly testify against them before Joseph McCarthy's House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 (via Encyclopedia.com and History Matters).

Disneyland and the FBI: Kickbacks for Narcs and Special Agents

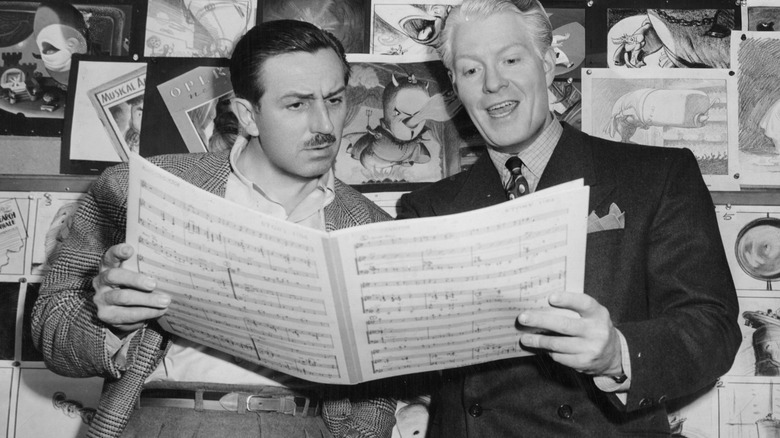

Retaliatory power against his enemies was not the only benefit of being an FBI informant. Thanks to his cooperation with J. Edgar Hoover, Walt Disney was granted access to film at the FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. In turn, Hoover got his own kickbacks from the powerful entertainment mogul: He was allowed to make minor edits to the scripts of several lesser-known Disney films (and one episode of "The Mickey Mouse Club," The New York Times reports). He also gave the FBI universal access to Disneyland (for "official" matters or, according to page six of his FBI file, even "recreational purposes").

Dubbed "Hollywood's Dark Prince" by biographer Marc Eliot and "Hollywood Tattler" by the Roanoke Times, Disney's reputation was tarnished by the (albeit not-unprecedented) news of his role in assisting Joseph McCarthy. McCarthyism and the House Un-American Activities Committee are now considered a shameful episode in America's past (as noted by History). Although Disney, in his public persona, was not shy about his anti-union stance (per Jacobin) and his strategic use of alarmist politics (via The Guardian), at the end of the day, his reports as an informant were ultimately motivated by what served him best. Far from the idyllic world of the Walt Disney Company's animated cartoons, Disney may have missed out on some of his own movies' lessons. In the words of the man himself, "Disneyland is a show" (via Brainy Quote).